Dugong facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dugong |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: |

Dugongidae

Gray, 1821

|

| Subfamily: |

Dugonginae

Simpson, 1932

|

| Genus: |

Dugong

Lacépède, 1799

|

| Species: |

D. dugon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dugong dugon (Müller, 1776)

|

|

|

|

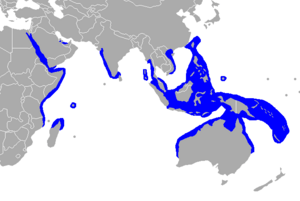

| Natural range of D. dugon. | |

The dugong, Dugong dugon, is a large mammal that lives its whole life in the sea.

They are sometimes called "sea cows" as they eat large amounts of sea grass. They live in warm, shallow areas where the sea grass grows. This area includes the north coast of Australia, and in other countries in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.

Dugongs are more closely related to elephants than to other sea creatures. Their closest aquatic relative is the manatee, a fresh water species found in America and West Africa.

The dugong can grow to about 3 m (10 ft) long and weigh as much as 400 kg (882 lb). They only come to the surface to breathe, and unlike seals, they never come up on the land. A baby dugong is called a calf. It drinks milk from its mother until about two years old. A dugong reaches its adult size between the ages of 9 and 17 years. The dugong can live for up to 70 years of age. They are greyto brown in color. They have a tail with flukes, like a whale, and flippers. They do not have a dorsal fin like a shark. They have a wide flat nose, small eyes, and small ears.

The dugong is a migratory animal, but very slow moving. Studies by James Cook University showed that while many dugongs traveled less than 15 km (9 mi), some went as far as 560 km (348 mi). Scientists believe that dugongs move long distances for several reasons. They may be looking for food, as cyclones or floods can affect the seagrass. Males may be following females, or looking for their own territory. If the water gets cold, less than 17 degrees Centigrade, they will travel to warmer areas.

Because of their size, the only other species to attack dugongs are sharks, the Saltwater Crocodile and killer whales.

Contents

Anatomy and morphology

The dugong's body is large with a cylindrical shape that tapers at both ends. It has thick, smooth skin that is a pale cream colour at birth, but darkens dorsally and laterally to brownish-to-dark-grey with age. The colour of a dugong can change due to the growth of algae on the skin. The body is sparsely covered in short hair, a common feature among sirenians which may allow for tactile interpretation of their environment. These hairs are most developed around the mouth, which has a large horseshoe-shaped upper lip forming a highly mobile muzzle. This muscular upper lip aids the dugong in foraging.

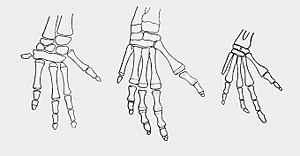

The dugong's tail flukes and flippers are similar to those of dolphins. These flukes are raised up and down in long strokes to move the animal forward, and can be twisted to turn. The forelimbs are paddle-like flippers which aid in turning and slowing. The dugong lacks nails on its flippers, which are only 15% of a dugong's body length. The tail has deep notches.

A dugong's brain weighs a maximum of 300 g (11 oz), about 0.1% of the animal's body weight. With very small eyes, dugongs have limited vision, but acute hearing within narrow sound thresholds. Their ears, which lack pinnae, are located on the sides of their head. The nostrils are located on top of the head and can be closed using valves. There are few differences between sexes; the body structures are almost the same. The lungs in a dugong are very long, extending almost as far as the kidneys, which are also highly elongated in order to cope with the saltwater environment. If wounded, a dugong's blood will clot rapidly.

The skull of a dugong is unique. The skull is enlarged with sharply down-turned premaxilla, which are stronger in males. The spine has between 57 and 60 vertebrae. Unlike in manatees, the dugong's teeth do not continually grow back via horizontal tooth replacement. The dugong has two incisors (tusks) which emerge in males during puberty. The female's tusks continue to grow without emerging during puberty, sometimes erupting later in life after reaching the base of the premaxilla. The number of growth layer groups in a tusk indicates the age of a dugong, and the cheekteeth move forward with age. The full dental formula of dugongs is 2.0.3.33.1.3.3, meaning they have two incisors, three premolars, and three molars on each side of their upper jaw, and three incisors, one canine, three premolars, and three molars on each side of their lower jaw. Like other sirenians, the dugong experiences pachyostosis, a condition in which the ribs and other long bones are unusually solid and contain little or no marrow. These heavy bones, which are among the densest in the animal kingdom, may act as a ballast to help keep sirenians suspended slightly below the water's surface.

An adult's length rarely exceeds 3 metres (9.8 ft). An individual this long is expected to weigh around 420 kilograms (926 lb). Weight in adults is typically more than 250 kilograms (551 lb) and less than 900 kilograms (1,984 lb). The largest individual recorded was 4.06 metres (13.32 ft) long and weighed 1,016 kilograms (2,240 lb), and was found off the Saurashtra coast of west India. Females tend to be larger than males.

Distribution and habitat

Dugongs are found in warm coastal waters from the western Pacific Ocean to the eastern coast of Africa, along an estimated 140,000 kilometres (86,992 mi) of coastline between 26° and 27° degrees to the north and south of the equator. Their historic range is believed to correspond to that of seagrasses from the Potamogetonaceae and Hydrocharitaceae families. The full size of the former range is unknown, although it is believed that the current populations represent the historical limits of the range, which is highly fractured. Today populations of dugongs are found in the waters of 37 countries and territories. Recorded numbers of dugongs are generally believed to be lower than actual numbers, due to a lack of accurate surveys. Despite this, the dugong population is thought to be shrinking, with a worldwide decline of 20 per cent in the last 90 years. They have disappeared from the waters of Hong Kong, Mauritius, and Taiwan, as well as parts of Cambodia, Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam. Further disappearances are likely.

Dugongs are generally found in warm waters around the coast with large numbers concentrated in wide and shallow protected bays. The dugong is the only strictly-marine herbivorous mammal, as all species of manatee utilise fresh water to some degree. Nonetheless, they can tolerate the brackish waters found in coastal wetlands, and large numbers are also found in wide and shallow mangrove channels and around leeward sides of large inshore islands, where seagrass beds are common. They are usually located at a depth of around 10 m (33 ft), although in areas where the continental shelf remains shallow dugongs have been known to travel more than 10 kilometres (6 mi) from the shore, descending to as far as 37 metres (121 ft), where deepwater seagrasses such as Halophila spinulosa are found. Special habitats are used for different activities. It has been observed that shallow waters are used as sites for calving, minimising the risk of predation. Deep waters may provide a thermal refuge from cooler waters closer to the shore during winter.

East Africa and South Asia

In the late 1960s, herds of up to 500 dugongs were observed off the coast of East Africa and nearby islands. Current populations in this area are extremely small, numbering 50 and below, and it is thought likely they will become extinct. The eastern side of the Red Sea is home to large populations numbering in the hundreds, and similar populations are thought to exist on the western side. In the 1980s, it was estimated there could be as many as 4,000 dugongs in the Red Sea. The Persian Gulf has the second-largest dugong population in the world, inhabiting most of the southern coast, and the current population is believed to number c. 7,500. However, recent studies revealed severe declines both in population size and distributions among the region. Dugong populations in Madagascar are poorly studied, but due to widespread exploitation it is thought they may have severely declined, with few surviving individuals. In Mozambique, most of the remaining local populations are very small and the largest (about 120 individuals) occurs at Bazaruto Island, but they have become rare in historical habitats such as in Maputo Bay and on Inhaca Island. In Tanzania, observations have recently been increased around the Mafia Island Marine Park where a hunt was intended by fishermen but failed in 2009. In the Seychelles, dugongs had been regarded as extinct in 18th century until a small number was discovered around the Aldabra Atoll. This population may belong to a different group than that distributed among the inner isles. Dugongs once thrived among the Chagos Archipelago and Sea Cow Island was named after the species, although the species no longer occurs in the region.

A highly isolated breeding population exists in the Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch, the only remaining population in western India. It is 1,500 kilometres (932 mi) from the population in the Persian Gulf, and 1,700 kilometres (1,056 mi) from the nearest population in India. Former populations in this area, centred on the Maldives and the Laccadive Islands, are presumed to be extinct. A population exists in the Gulf of Mannar Marine National Park and the Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka, but it is seriously depleted. Recoveries of seagrass beds along former ranges of dugongs, such as the Chilika Lake have been confirmed in recent years, rising hopes for re-colorizations of the species. The population around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are known only from a few records, and although the population was large during British rule, it is now believed to be small and scattered. Once distributed throughout the coastal belt in Sri Lanka, the dugong numbers have declined in last two decades.

Southern Pacific outside of Australia

A small population exists today along the southern coast of China, where efforts are being made to protect it, including ranging in Guangxi. Despite these efforts, numbers continue to decrease, and in 2007 it was reported that no more dugong could be found on the west coast of the island of Hainan. Historically, dugongs were also present in the southern parts of the Yellow Sea. In Vietnam, dugongs have been restricted mostly to the provinces of Kiên Giang and Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu, including Phu Quoc Island and Con Dao Island, which hosted large populations in the past. Con Dao is now the only site in Vietnam where dugong are regularly seen, protected within the Côn Đảo National Park. Nonetheless, dangerously low levels of awarenesses for conservation of marine organisms in Vietnam and Cambodia may result in increased intentional or unintentional catches, and illegal trade is a potential danger for local dugongs. On Phu Quoc, the first 'Dugong Festival' was held in 2014, aiming to raise awareness of these issues.

In Thailand, the present distribution of dugongs is restricted to 6 provinces along the Andaman Sea, and very few dugongs are present in the Gulf of Thailand. The Gulf of Thailand was historically home to large number of the animals, but none have been sighted in the west of the gulf in recent years, and the remaining population in the east is thought to be very small and possibly declining. Dugongs are believed to exist in the Straits of Johor in very small numbers. The waters around Borneo support a small population, with more scattered throughout the Malay archipelago. All the islands of the Philippines are believed to have once provided habitats for dugongs, which were common until the 1970s. Populations exist around the Solomon Islands archipelago and New Caledonia, stretching to an easternmost population in Vanuatu. A highly isolated population lives around the islands of Palau.

A single dugong lives at Cocos (Keeling) Islands although the animal is thought to be a vagrant.

Northern Pacific

Today, possibly the smallest and northernmost population of dugongs exists around the Ryukyu islands, and a population formerly existed off Taiwan. An endangered population of 50 or fewer dugongs, possibly as few as three individuals, survives around Okinawa. New sightings of a cow-calf pair have been reported in 2017, indicating a possible breeding had occurred in these waters. A single individual was recorded in Amami Oshima, at the northernmost edge of the dugong's historic range, more than 40 years after the last previous recorded sighting. A vagrant strayed into port near Ushibuka, Kumamoto, and died due to poor health. Historically, the Yaeyama Islands held a large concentration of dugongs, with more than 300 individuals. On Aragusuku Island, large quantities of skulls are preserved at an utaki that outsiders are strictly forbidden to enter. Dugong populations in these areas were reduced by historical hunts as payments to the Ryukyu Kingdom, before being wiped out because of large-scale illegal hunting and fishing using destructive methods such as dynamite fishing after the Second World War.

Populations around Taiwan appear to be almost extinct, although remnant individuals may visit areas with rich seagrass beds such as Dongsha Atoll. Some of the last reported sightings were made in Kenting National Park in 1950s and 60s. There had been occasional records of vagrants at the Northern Mariana Islands prior to 1985. It is unknown how much mixing there was between these populations historically. Some theorise that populations existed independently, for example that the Okinawan population were isolated members derived from the migration of a Philippine subspecies. Others postulate that the populations formed part of a super-population where migration between Ryukyu, Taiwan, and the Philippines was common.

Australia

Australia is home to the largest population, stretching from Shark Bay in Western Australia to Moreton Bay in Queensland. The population of Shark Bay is thought to be stable with over 10,000 dugongs. Smaller populations exist up the coast, including one in Ashmore reef. Large numbers of dugongs live to the north of the Northern Territory, with a population of over 20,000 in the gulf of Carpentaria alone. A population of over 25,000 exists in the Torres Strait such as off Thursday Island, although there is significant migration between the strait and the waters of New Guinea. The Great Barrier Reef provides important feeding areas for the species; this reef area houses a stable population of around 10,000, although the population concentration has shifted over time. Large bays facing north on the Queensland coast provide significant habitats for dugong, with the southernmost of these being Hervey Bay and Moreton Bay. Dugongs had been occasional visitors along the Gold Coast where an (re)establishment of a local population through range expansions has started recently.

Extinct Mediterranean population

It has been confirmed that dugongs once inhabited the water of the Mediterranean possibly until after the rise of civilizations along the inland sea. This population possibly shared ancestry with the Red Sea population, and the Mediterranean population had never been large due to geographical factors and climate changes. The Mediterranean is the region where the Dugongidae originated in the mid-late Eocene, along with Caribbean Sea.

Ecology and life history

Dugongs are long lived, and the oldest recorded specimen reached age 73. They have few natural predators, although animals such as crocodiles, killer whales, and sharks pose a threat to the young, and a dugong has also been recorded to have died from trauma after being impaled by a stingray barb. A large number of infections and parasitic diseases affect dugongs. Detected pathogens include helminths, cryptosporidium, different types of bacterial infections, and other unidentified parasites. 30% of dugong deaths in Queensland since 1996 are thought to be because of disease.

Although they are social animals, they are usually solitary or found in pairs due to the inability of seagrass beds to support large populations. Gatherings of hundreds of dugongs sometimes happen, but they last only for a short time. Because they are shy, and do not approach humans, little is known about dugong behaviour. They can go six minutes without breathing (though about two and a half minutes is more typical), and have been known to rest on their tail to breathe with their heads above water. They can dive to a maximum depth of 39 metres (128 ft); they spend most of their lives no deeper than 10 metres (33 ft). Communication between individuals is through chirps, whistles, barks, and other sounds that echo underwater. Different sounds have been observed with different amplitudes and frequencies, implying different purposes. Visual communication is limited due to poor eyesight, and is mainly used for activities such as lekking for courtship purposes. Mothers and calves are in almost constant physical contact, and calves have been known to reach out and touch their mothers with their flippers for reassurance.

Dugongs are semi-nomadic, often travelling long distances in search of food, but staying within a certain range their entire life. Large numbers often move together from one area to another. It is thought that these movements are caused by changes in seagrass availability. Their memory allows them to return to specific points after long travels. Dugong movements mostly occur within a localised area of seagrass beds, and animals in the same region show individualistic patterns of movement. Daily movement is affected by the tides. In areas where there is a large tidal range, dugongs travel with the tide in order to access shallower feeding areas. In Moreton Bay, dugongs often travel between foraging grounds inside the bay and warmer oceanic waters. At higher latitudes dugongs make seasonal travels to reach warmer water during the winter. Occasionally individual dugongs make long-distance travels over many days, and can travel over deep ocean waters. One animal was seen as far south as Sydney. Although they are marine creatures, dugongs have been known to travel up creeks, and in one case a dugong was caught 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) up a creek near Cooktown.

Feeding

Dugongs, along with other sirenians, are referred to as "sea cows" because their diet consists mainly of sea-grass. When eating they ingest the whole plant, including the roots, although when this is impossible they will feed on just the leaves. A wide variety of seagrass has been found in dugong stomach contents, and evidence exists they will eat algae when seagrass is scarce. Although almost completely herbivorous, they will occasionally eat invertebrates such as jellyfish, sea squirts, and shellfish. Dugongs in Moreton Bay, Australia, are omnivorous, feeding on invertebrates such as polychaetes or marine algae when the supply of their choice grasses decreases. In other southern areas of both western and eastern Australia, there is evidence that dugongs actively seek out large invertebrates. This does not apply to dugongs in tropical areas.

Most dugongs do not feed from lush areas, but where the seagrass is more sparse. Additional factors such as protein concentration and regenerative ability also affect the value of a seagrass bed. The chemical structure and composition of the seagrass is important, and the grass species most often eaten are low in fibre, high in nitrogen, and easily digestible. In the Great Barrier Reef, dugongs feed on low-fibre high-nitrogen seagrass such as Halophila and Halodule, so as to maximize nutrient intake instead of bulk eating. Seagrasses of a lower seral are preferred, where the area has not fully vegetated. Only certain seagrass meadows are suitable for dugong consumption, due to the dugong's highly specialised diet. There is evidence that dugongs actively alter seagrass species compositions at local levels. Dugongs may search out deeper seagrass. Feeding trails have been observed as deep as 33 metres (108 ft), and dugongs have been seen feeding as deep as 37 metres (121 ft). Dugongs are relatively slow moving, swimming at around 10 kilometres per hour (6.2 mph). When moving along the seabed to feed they walk on their pectoral fins.

Dugong feeding may favor the subsequent growth low-fibre, high-nitrogen seagrasses such as Halophilia and Halodule. Species such as Zosteria Capricorni are more dominant in established seagrass beds, but grow slowly, while Halophilia and Halodule grow quickly in the open space left by dugong feeding. This behavior is known as cultivation grazing, and favors the rapidly growing, higher nutrient seagrasses that dugongs prefer. Dugongs may also prefer to feed on younger, less fibrous strands of seagrasses, and cycles of cultivation feeding at different seagrass meadows may provide them with a greater number of younger plants.

Due to their poor eyesight, dugongs often use smell to locate edible plants. They also have a strong tactile sense, and feel their surroundings with their long sensitive bristles. They will dig up an entire plant and then shake it to remove the sand before eating it. They have been known to collect a pile of plants in one area before eating them. The flexible and muscular upper lip is used to dig out the plants. This leaves furrows in the sand in their path.

Reproduction and parental care

A dugong reaches maturity between the ages of eight and eighteen, older than in most other mammals. The way that females know how a male has reached maturity is by the eruption of tusks in the male since tusks erupt in males when testosterone levels reach a high enough level. The age when a female first gives birth is disputed, with some studies placing the age between ten and seventeen years, while others place it as early as six years. Despite the longevity of the dugong, which may live for 50 years or more, females give birth only a few times during their life, and invest considerable parental care in their young. The time between births is unclear, with estimates ranging from 2.4 to 7 years.

Females give birth after a 13–15 month gestation, usually to just one calf. Birth occurs in very shallow water, with occasions known where the mothers were almost on the shore. As soon as the young is born the mother pushes it to the surface to take a breath. Newborns are already 1.2 metres (4 ft) long and weigh around 30 kilograms (66 lb). Once born, they stay close to their mothers, possibly to make swimming easier. The calf nurses for 14–18 months, although it begins to eat seagrasses soon after birth. A calf will only leave its mother once it has matured.

Importance to humans

Dugongs have historically provided easy targets for hunters, who killed them for their meat, oil, skin, and bones. As the anthropologist A. Asbjørn Jøn has noted, they are often considered as the inspiration for mermaids, and people around the world developed cultures around dugong hunting. In some areas it remains an animal of great significance, and a growing ecotourism industry around dugongs has had economic benefit in some countries.

There is a 5,000-year-old wall painting of a dugong, apparently drawn by neolithic peoples, in Tambun Cave, Ipoh, Malaysia. This was discovered by Lieutenant R.L Rawlings in 1959 while on a routine patrol. During the Renaissance and the Baroque eras, dugongs were often exhibited in wunderkammers. They were also presented as Fiji mermaids in sideshows.

Dugong meat and oil have traditionally been some of the most valuable foods of Aboriginal Australianss and Torres Strait Islanders. Some Aboriginal Australians regard dugongs as part of their Aboriginality. Dugongs have also played a role in legends in Kenya, and the animal is known there as the "Queen of the Sea". Body parts are used as food, medicine, and decorations. In the Gulf states, dugongs served not only as a source of food, but their tusks were used as sword handles. Dugong oil is important as a preservative and conditioner for wooden boats to people in around the Gulf of Kutch in India. Dugong ribs were used to make carvings in Japan. In Southern China dugongs were traditionally regarded as a "miraculous fish", and it was bad luck to catch them. A wave of immigration beginning at the end of the 1950s resulted in dugongs being hunted for food. In the Philippines dugongs are thought to bring bad luck, and parts of them are used to ward against evil spirits. In areas of Thailand it is believed that the dugong's tears form a powerful love potion, while in parts of Indonesia they are considered reincarnations of women. In Papua New Guinea they are seen as a symbol of strength.

Dugongs' or sea cows' hides have been thought to have been used as coverings in the building of the Old Testament portable worship tent known as the Tabernacle.

Conservation

Dugong numbers have decreased in recent times. For a population to remain stable, 95 per cent of adults must survive the span of one year. The estimated percentage of females humans can kill without depleting the population is 1–2%. This number is reduced in areas where calving is minimal due to food shortages. Even in the best conditions a population is unlikely to increase more than 5% a year, leaving dugongs vulnerable to over-exploitation. The fact that they live in shallow waters puts them under great pressure from human activity. Research on dugongs and the effects of human activity on them has been limited, mostly taking place in Australia. In many countries, dugong numbers have never been surveyed. As such, trends are uncertain, with more data needed for comprehensive management. The only data stretching back far enough to mention population trends comes from the urban coast of Queensland, Australia. The last major worldwide study, made in 2002, concluded that the dugong was declining and possibly extinct in a third of its range, with unknown status in another half.

Human activity

Despite being legally protected in many countries, the main causes of population decline remain anthropogenic and include hunting, habitat degradation, and fishing-related fatalities. Entanglement in fishing nets has caused many deaths, although there are no precise statistics. Most issues with industrial fishing occur in deeper waters where dugong populations are low, with local fishing being the main risk in shallower waters. As dugongs cannot stay underwater for a very long period, they are highly prone to deaths due to entanglement. The use of shark nets has historically caused large numbers of deaths, and they have been eliminated in most areas and replaced with baited hooks. Hunting has historically been a problem too, although in most areas they are no longer hunted, with the exception of certain indigenous communities. In areas such as northern Australia, hunting remains the greatest impact on the dugong population.

Vessel strikes have proved a problem for manatees, but the relevance of this to dugongs is unknown. Increasing boat traffic has increased danger, especially in shallow waters. Ecotourism has increased in some countries, although effects remain undocumented. It has been seen to cause issues in areas such as Hainan due to environmental degradation. Modern farming practise and increased land clearing have also had an impact, and much of the coastline of dugong habitats is undergoing industrialisation, with increasing human populations. Dugongs accumulate heavy metal ions in their tissues throughout their lives, more so than other marine mammals. The effects are unknown. While international cooperation to form a conservative unit has been undertaken, socio-political needs are an impediment to dugong conservation in many developing countries. The shallow waters are often used as a source of food and income, problems exacerbated by aid used to improve fishing. In many countries, legislation does not exist to protect dugongs, and if it does it is not enforced.

Oil spills are a danger to dugongs in some areas, as is land reclamation. In Okinawa the small dugong population is threatened by United States military activity. Plans exist to build a military base close to the Henoko reef, and military activity also adds the threats of noise pollution, chemical pollution, soil erosion, and exposure to depleted uranium. The military base plans have been fought in US courts by some Okinawans, whose concerns include the impact on the local environment and dugong habitats. It was later revealed that the government of Japan was hiding evidence of the negative effects of ship lanes and human activities on dugongs observed during surveys carried out off Henoko reef. One of the three individuals has not been observed since June 2015, corresponding to the start of the excavation operations.

Environmental degradation

If dugongs do not get enough to eat they may calve later and produce fewer young. Food shortages can be caused by many factors, such as a loss of habitat, death and decline in quality of seagrass, and a disturbance of feeding caused by human activity. Sewage, detergents, heavy metal, hypersaline water, herbicides, and other waste products all negatively affect seagrass meadows. Human activity such as mining, trawling, dredging, land reclamation, and boat propeller scarring also cause an increase in sedimentation which smothers seagrass and prevents light from reaching it. This is the most significant negative factor affecting seagrass.

Halophila ovalis—one of the dugong's preferred species of seagrass—declines rapidly due to lack of light, dying completely after 30 days. Extreme weather such as cyclones and floods can destroy hundreds of square kilometres of seagrass meadows, as well as washing dugongs ashore. The recovery of seagrass meadows and the spread of seagrass into new areas, or areas where it has been destroyed, can take over a decade. Most measures for protection involve restricting activities such as trawling in areas containing seagrass meadows, with little to no action on pollutants originating from land. In some areas water salinity is increased due to wastewater, and it is unknown how much salinity seagrass can withstand.

Dugong habitat in the Oura Bay area of Henoko, Okinawa, Japan, is currently under threat from land reclamation conducted by Japanese Government in order to build a US Marine base in the area. In August 2014, preliminary drilling surveys were conducted around the seagrass beds there. The construction is expected to seriously damage the dugong population's habitat, possibly leading to local extinction.

Capture and captivity

The Australian state of Queensland has sixteen dugong protection parks, and some preservation zones have been established where even Aboriginal Peoples are not allowed to hunt. Capturing animals for research has caused only one or two deaths; dugongs are expensive to keep in captivity due to the long time mothers and calves spend together, and the inability to grow the seagrass that dugongs eat in an aquarium. Only one orphaned calf has ever been successfully kept in captivity.

Worldwide, only four dugongs are held in captivity. A female from the Philippines lives at Toba Aquarium in Toba, Mie, Japan. A male also lived there until he died on 10 February 2011. The second resides in Sea World Indonesia, after having been rescued from a fisherman's net and treated. The last two—a male and a female—are kept at Sydney Aquarium, where they have resided since they were juveniles.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Dugong dugon para niños

In Spanish: Dugong dugon para niños