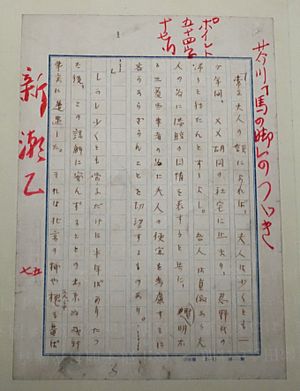

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Native name |

芥川 龍之介

|

||||

| Born | Ryūnosuke Niihara (新原 龍之介) 1 March 1892 Kyōbashi, Tokyo, Empire of Japan |

||||

| Died | 24 July 1927 (aged 35) Tokyo, Empire of Japan |

||||

| Occupation | Writer | ||||

| Language | Japanese | ||||

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University | ||||

| Genre | Short stories | ||||

| Literary movement | Modernism | ||||

| Notable works |

|

||||

| Spouse | Fumi Akutagawa | ||||

| Children | 3 (including Yasushi Akutagawa) | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 芥川 龍之介 | ||||

| Hiragana | あくたがわ りゅうのすけ | ||||

|

|||||

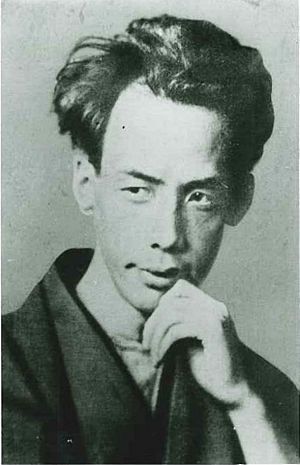

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (born March 1, 1892 – died July 24, 1927) was a famous Japanese writer. He was active during the Taishō period in Japan. Many people call him the "father of the Japanese short story". Japan's most important literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him.

Contents

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa's Early Life

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa was born in Tokyo on March 1, 1892. He was the oldest son of Toshizō Niihara, a businessman, and his wife Fuku. His family owned a milk business. Soon after he was born, his mother became unwell. Because of this, his maternal uncle, Dōshō Akutagawa, adopted and raised him. This is how he got the Akutagawa family name.

From a young age, Ryūnosuke loved Chinese literature. He also enjoyed reading works by famous Japanese writers like Mori Ōgai and Natsume Sōseki.

In 1910, he started high school. There, he became friends with classmates who would also become writers later on. In 1913, he went to Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) to study English literature. He began writing stories while he was still a student.

In 1916, he got engaged to Fumi Tsukamoto, and they married in 1918. They had three sons: Hiroshi, Takashi, and Yasushi Akutagawa.

After finishing university, Akutagawa taught English language for a short time at a naval school. But he soon decided to focus all his time on writing.

Akutagawa's Writing Career

In 1914, Akutagawa and his high school friends started a literary journal called Shinshichō ("New Currents of Thought"). They published their own stories and translations of works by Western writers.

In 1915, while still a student, Akutagawa published his short story "Rashōmon". This story was based on an old Japanese tale from the 12th century. His friends did not like it much. However, Akutagawa was brave and visited his favorite writer, Natsume Sōseki. In early 1916, he published "Hana" ("The Nose"). Sōseki praised this story, and it brought Akutagawa his first taste of fame.

Around this time, Akutagawa also started writing haiku poems. He wrote many short stories that were set in old Japan, like the Heian period or Edo period. These stories often retold old tales or historical events in a new way. Some examples are Jigoku hen ("Hell Screen", 1918) and Hōkyōnin no shi ("The Death of a Christian", 1918). He also wrote stories set in more modern times, like Mikan ("Mandarin Oranges", 1919).

In 1921, Akutagawa took a break from writing. He spent four months in China as a reporter for a newspaper. The trip was difficult, and his health was affected. After he returned, he published Yabu no naka ("In a Grove", 1922).

How Akutagawa Was Influenced

Akutagawa believed that literature should be for everyone. He thought it could bring together Western and Japanese cultures. You can see this idea in his stories. He often took old stories from different cultures and times and rewrote them with new ideas.

Akutagawa's Later Life

Towards the end of his life, Akutagawa's health became very poor. Many of his later works were about his own life and feelings. He sometimes used parts of his own diaries in his stories. Some of these works include Daidōji Shinsuke no hansei ("The Early Life of Daidōji Shinsuke", 1925).

His last works include Kappa (1927), which is a funny story about a creature from Japanese folklore. He also wrote Haguruma ("Spinning Gears", 1927) and Aru ahō no isshō ("A Fool's Life").

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa passed away at the age of 35.

Akutagawa's Legacy and Adaptations

During his short life, Akutagawa wrote about 150 short stories. Many of these stories have been made into other forms of media.

- The famous 1950 film Rashōmon by Akira Kurosawa is based on Akutagawa's story In a Bamboo Grove. The film also uses the title and setting from Akutagawa's story Rashōmon.

- A Ukrainian composer named Victoria Poleva created a ballet called Gagaku (1994), based on Akutagawa's Hell Screen.

- Japanese composer Mayako Kubo wrote an opera called Rashomon, also based on his story.

The idea from his story In a Grove, where different characters tell conflicting versions of the same event, has become a common way to tell stories.

In 1935, Akutagawa's friend Kan Kikuchi created a special literary award for new writers. It is called the Akutagawa Prize and is named in his honor.

In 2020, a film called A Stranger in Shanghai was made. It shows Akutagawa's time as a reporter in China.

Selected Works

| Year | Japanese title | English title(s) | English translator(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | 老年 Rōnen |

"Old Age" | Ryan Choi |

| 1915 | 羅生門 Rashōmon |

"Rashōmon" | Glen Anderson; Takashi Kojima; Jay Rubin; Glenn W. Shaw |

| 1916 | 鼻 Hana |

"The Nose" | Glen Anderson; Takashi Kojima; Jay Rubin; Glen W. Shaw |

| 芋粥 Imogayu |

"Yam Gruel" | Takashi Kojima | |

| 手巾 Hankechi |

"The Handkerchief" | Charles De Wolf; Glenn W. Shaw | |

| 煙草と悪魔 Tabako to Akuma |

"Tobacco and the Devil" | Glenn W. Shaw | |

| 1917 | 尾形了斎覚え書 Ogata Ryōsai Oboe gaki |

"Dr. Ogata Ryosai: Memorandum" | Jay Rubin |

| 戯作三昧 Gesakuzanmai |

"Absorbed in writing popular novels" | ||

| 首が落ちた話 Kubi ga ochita hanashi |

"The Story of a Head That Fell Off" | Jay Rubin | |

| 1918 | 蜘蛛の糸 Kumo no Ito |

"The Spider's Thread" | Dorothy Britton; Charles De Wolf; Bryan Karetnyk; Takashi Kojima; Howard Norman; Jay Rubin; Glenn W. Shaw |

| 地獄変 Jigokuhen |

"Hell Screen" | Bryan Karetnyk; Takashi Kojima; Howard Norman; Jay Rubin | |

| 枯野抄 Kareno shō |

"A Commentary on the Desolate Field for Bashou" | ||

| 邪宗門 Jashūmon |

"Jashūmon" | W.H.H. Norman | |

| 奉教人の死 Hōkyōnin no Shi |

"The Death of a Disciple" | Charles De Wolf | |

| 袈裟と盛遠 Kesa to Moritō |

"Kesa and Morito" | Takashi Kojima; Charles De Wolf | |

| 1919 | 魔術 Majutsu |

"Magic" | |

| 竜 Ryū |

"Dragon: the Old Potter's Tale" | Jay Rubin | |

| 1920 | 舞踏会 Butōkai |

"A Ball" | Glenn W. Shaw |

| 秋 Aki |

"Autumn" | Charles De Wolf | |

| 南京の基督 Nankin no Kirisuto |

"Christ in Nanking" | Van C. Gessel | |

| 杜子春 Toshishun |

"Tu Tze-chun" | Dorothy Britton | |

| アグニの神 Aguni no Kami |

"God of Aguni" | ||

| 1921 | 山鴫 Yama-shigi |

"A Snipe" | |

| 秋山図 Shūzanzu |

"Autumn Mountain" | ||

| 上海游記 Shanhai Yūki |

"A Report on the Journey of Shanghai" | ||

| 1922 | 藪の中 Yabu no Naka |

"In a Grove," or "In a Bamboo Grove" | Glen Anderson; Bryan Karetnyk; Takashi Kojima; Jay Rubin |

| 将軍 Shōgun |

"The General" | Bryan Karetnyk; W.H.H. Norman | |

| トロッコ Torokko |

"A Lorry" | ||

| 1923 | 保吉の手帳から Yasukichi no Techō kara |

"From Yasukichi's Notebook" | |

| 1924 | 一塊の土 Ikkai no Tsuchi |

"A Clod of Earth" | Takashi Kojima |

| "Writer's Craft" | Jay Rubin | ||

| 1925 | 大導寺信輔の半生 Daidōji Shinsuke no Hansei |

"Daidōji Shinsuke: The Early Years" | Jay Rubin |

| 侏儒の言葉 Shuju no Kotoba |

"Aphorisms by a Pygmy" | ||

| 1926 | 点鬼簿 Tenkibo |

"Death Register" | Jay Rubin |

| 1927 | 玄鶴山房 Genkaku Sanbō |

"Genkaku Sanbo" | Takashi Kojima |

| 蜃気楼 Shinkirō |

"A Mirage" | ||

| 河童 Kappa |

Kappa | Geoffrey Bownas; Seiichi Shiojiri | |

| 仙人 Sennin |

"The Wizard" | Charles De Wolf | |

| 文芸的な、余りに文芸的な Bungei-teki na, amarini Bungei-teki na |

"Literary, All-Too-Literary" | ||

| 歯車 Haguruma |

"Spinning Gears" or "Cogwheels" | Charles De Wolf; Howard Norman; Jay Rubin | |

| 或阿呆の一生 Aru Ahō no Isshō |

"A Fool's Life" or "The Life of a Fool" | Charles De Wolf; Jay Rubin | |

| 西方の人 Saihō no Hito |

"The Man of the West" | ||

| 1927 | 或旧友へ送る手記 Aru Kyūyū e Okuru Shuki |

"A Note to a Certain Old Friend" | |

| 1923–1927 | 侏儒の言葉 Shuju no Kotoba |

"Dwarf's Words" | Shin IWATA (2023) |

See also

In Spanish: Ryūnosuke Akutagawa para niños

In Spanish: Ryūnosuke Akutagawa para niños