Sarah Bernhardt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sarah Bernhardt

|

|

|---|---|

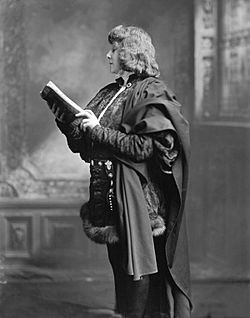

Sarah Bernhardt in June 1877, during a visit to Boston, Massachusetts

|

|

| Born |

Sara-Marie-Henriette Rosine Bernardt

October 22, 1844 |

| Died | March 26, 1923 (aged 78) Paris, France

|

| Years active | 1862–1923 |

| Spouse(s) | Ambroise Aristide Damala (1882–1889) |

Sarah Bernhardt (23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress, and has often been called "the most famous actress in the history of the world". Bernhardt made her fame on the stages of Europe in the 1870s, and was soon working in Europe and the United States. She developed a reputation as a serious actress, getting the nickname "The Divine Sarah."

Contents

Early life

Henriette-Rosine Bernard was born at 5 rue de L'École-de-Médicine in the Latin Quarter of Paris on 22 October 1844. She was the daughter of Judith Bernard. The name of her father was not recorded for a long time. We know now that he was an attorney in Le Havre. She later added the letter "H" to her first and last name, and used the name of Edouard Bernardt, her mother's brother, as the name of her father.

Bernhardt later wrote that her father's family paid for her education, insisted she be baptised as a Catholic, and left a large sum to be paid when she came of age. Her mother travelled frequently, and saw little of her daughter. She placed Bernhardt with a nurse in Brittany, then in a cottage in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine.

When Bernhardt was seven, her mother sent her to a boarding school for young ladies in the Paris suburb of Auteuil, paid with funds from her father's family. There, she acted in her first theatrical performance in the play Clothilde, where she held the role of the Queen of the Fairies. At the age of 10, Bernhardt was admitted to Grandchamp, an exclusive Augustine convent school near Versailles.

In 1857, Bernhardt learned that her father had died overseas. Her mother summoned a family council, including Morny, to decide what to do with her. Charles de Morny, Duke of Morny, a family friend and a patron of her mother, proposed that Bernhardt should become an actress, an idea that horrified Bernhardt, as she had never been inside a theatre. Morny arranged for her to attend her first theatre performance at the Comédie Française in a party which included her mother, Morny, and his friend Alexandre Dumas. The play they attended was Britannicus, by Jean Racine, followed by the classical comedy Amphitryon by Plautus. Bernhardt was so moved by the emotion of the play, she began to sob loudly, disturbing the rest of the audience. Morny and others in their party were angry at her and left, but Dumas comforted her, and later told Morny that he believed that she was destined for the stage. After the performance, Dumas called her "my little star".

Morny used his influence to arrange for Bernhardt to audition. Dumas coached her. The jury was composed five leading actors and actresses from the Comédie Française. She was supposed to recite verses from Racine, but no one had told her that she needed someone to give her cues as she recited. Bernhardt told the jury she would instead recite the fable of the Two Pigeons by La Fontaine. The jurors were skeptical, but the fervor of her recitation won them over, and she was invited to become a student.

Career

Bernhardt studied acting at the Conservatory from January 1860 until 1862. She was then offered a place as a pensionnaire at the Théâtre Français, at a minimum salary.

Bernhardt made her debut with the company on 31 August 1862 in the title role of Racine's Iphigénie. Her premiere was not a success. She experienced stage fright and rushed her lines. Some audience members made fun of her thin figure.

Bernhardt did not remain long with the Comédie-Française. She played Henrietta in Molière's Les Femmes Savantes and Hippolyte in L'Étourdi, and the title role in Scribe's Valérie, but did not impress the critics, or the other members of the company, who had resented her rapid rise. The weeks passed, but she was given no further roles and was later asked to leave.

Her family could not understand her departure from the theater; it was inconceivable to them that anyone would walk away from the most prestigious theatre in Paris at age 18. Instead, she went to a popular theatre, the Gymnase, where she became an understudy to two of the leading actresses. She almost immediately caused an offstage scandal, when she was invited to recite poetry at a reception at the Tuileries Palace hosted by Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie, along with other actors of the Gymnase. She chose to recite two romantic poems by Victor Hugo, unaware that Hugo was a bitter critic of the emperor. Following the first poem, the emperor and empress rose and walked out, followed by the court and the other guests. Her next role at the Gymnase, as a foolish Russian princess, was entirely unsuited for her; her mother told her that her performance was "ridiculous". She decided abruptly to quit the theater to travel. She went briefly to Spain, then, at the suggestion of Alexandre Dumas, to Belgium.

She carried to Brussels letters of introduction from Dumas, and was admitted to the highest levels of society. According to some later accounts, she attended a masked ball in Brussels where she met the Belgian aristocrat Henri, Hereditary Prince de Ligne, and the two became romantically involved. On 22 December 1864, the 20-year-old actress gave birth to her only child, Maurice Bernhardt.

To support herself after the birth of Maurice, Bernhardt played minor roles and understudies at the Porte Saint-Martin theatre, a popular melodrama theatre. In early 1866, she obtained a reading with Felix Duquesnel, director of the Théâtre de L'Odéon (Odéon) on the Left Bank. Duquesnel was enchanted; he hired her for the theater at a modest salary of 150 francs a month, which he paid out of his own pocket. The Odéon was second in prestige only to the Comédie Française, and unlike that very traditional theatre, specialised in more modern productions. Her first performances with the theatre were not successful. Soon, however, with different plays and more experience, her performances improved; she was praised for her performance of Cordelia in King Lear.

Her breakthrough performance was in the 1868 revival of Kean by Alexandre Dumas, in which she played the female lead part of Anna Danby. At the final curtain, she received an enormous ovation, and Dumas hurried backstage to congratulate her. When she exited the theatre, a crowd had gathered at the stage door and tossed flowers at her. Her salary was immediately raised to 250 francs a month.

Her next success was her performance in François Coppée's Le Passant, which premiered at the Odéon on 14 January 1868, playing the part of the boy troubadour, Zanetto, in a romantic renaissance tale. It played for 150 performances, plus a command performance at the Tuileries Palace for Napoleon III and his court. Afterwards, the emperor sent her a brooch with his initials written in diamonds.

Bernhardt lived with her longtime friend and assistant Madame Guérard and her son in a small cottage in the suburb of Auteuil, and drove herself to the theatre in a small carriage. She developed a close friendship with the writer George Sand, and performed in two plays that she authored.

In 1869, as she became more prosperous, she moved to a larger seven-room apartment at 16 rue Auber in the center of Paris. Her mother began to visit her for the first time in years, and her grandmother, a strict Orthodox Jew, moved into the apartment to take care of Maurice. Bernhardt added a maid and a cook to her household, as well as the beginning of a collection of animals; she had one or two dogs with her at all times, and two turtles moved freely around the apartment.

In 1868, a fire completely destroyed her apartment, along with all of her belongings. She had neglected to purchase insurance. The brooch presented to her by the emperor and her pearls melted, as did the tiara presented by one of her admirers, Khalid Bey. She found the diamonds in the ashes, and the managers of the Odéon organised a benefit performance. The most famous soprano of the time, Adelina Patti, performed for free. In addition, the grandmother of her father donated 120,000 francs. Bernhardt was able to buy an even larger residence, with two salons and a large dining room, at 4 rue de Rome.

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War abruptly interrupted her theatrical career. The news of the defeat of the French Army, the surrender of Napoleon III at Sedan, and the proclamation of the Third French Republic on 4 September 1870 was followed by a siege of the city by the Prussian Army. Paris was cut off from news and from its food supply, and the theatres were closed. Bernhardt took charge of converting the Odéon into a hospital for soldiers wounded in the battles outside the city. She organised the placement of 32 beds in the lobby and the foyers, brought in her personal chef to prepare soup for the patients, and persuaded her wealthy friends and admirers to donate supplies for the hospital. Besides organising the hospital, she worked as a nurse, assisting the chief surgeon with amputations and operations. When the coal supply of the city ran out, Bernhardt used old scenery, benches, and stage props for fuel to heat the theater. In early January 1871, after 16 weeks of the siege, the Germans began to bombard the city with long-range cannons. The patients had to be moved to the cellar, and before long, the hospital was forced to close. Bernhardt arranged for serious cases to be transferred to another military hospital, and she rented an apartment on rue de Provence to house the remaining 20 patients. By the end of the siege, Bernhardt's hospital had cared for more than 150 wounded soldiers.

The French government signed an armistice on 19 January 1871, and Bernhardt learned that her son and family had been moved to Hamburg. She went to the new chief executive of the French Republic, Adolphe Thiers, and obtained a pass to go to Germany to return them. When she returned to Paris several weeks later, the city was under the rule of the Paris Commune. She moved again, taking her family to Saint-Germain-en-Laye. She later returned to her apartment on the rue de Rome in May, after the Commune was defeated by the French Army.

The Tuileries Palace, city hall of Paris, and many other public buildings had been burned by the Commune or damaged in the fighting, but the Odéon was still intact. Charles-Marie Chilly, the co-director of the Odéon, came to her apartment to announce that the theaters would reopen in October 1871, and he asked her to play the lead in a new play, Jean-Marie by André Theuriet. Bernhardt replied that she was finished with the theatre and was going to move to Brittany and start a farm. Chilly, who knew Bernhardt's moods well, told her that he understood and accepted her decision, and would give the role to Jane Essler, a rival actress. According to Chilly, Bernhardt immediately jumped up from the sofa and asked when the rehearsals would begin.

The play premiered on 16 January 1872. The opening night was attended by the Prince of Wales and by Victor Hugo.

Ruy Blas played to packed houses. A few months after it opened, Bernhardt received an invitation from Emile Perrin, Director of the Comédie Française, asking if she would return, and offering her 12,000 francs a year, compared with less than 10,000 at the Odéon. Bernhardt asked Chilly if he would match the offer, but he refused. Always pressed by her growing expenses and growing household to earn more money, she announced her departure from the Odéon when she finished the run of Ruy Blas. Chilly responded with a lawsuit, and she was forced to pay 6,000 francs of damages.

She formally returned to the Comédie Francaise on 1 October 1872, and quickly took on some of the more famous and demanding roles in French theatre. She played Junie in Britannicus by Jean Racine, the male role of Cherubin in The Marriage of Figaro by Pierre Beaumarchais, and the lead in Voltaire's five-act tragedy Zaïre. In 1873, with just 74 hours to learn the lines and practice the part, she played the lead in Racine's Phèdre, playing opposite the celebrated tragedian, Jean Mounet-Sully. Phèdre became her most famous classical role, performed over the years around the world, often for audiences who knew little or no French; she made them understand by her voice and gestures.

She maintained a highly theatrical lifestyle in her house on the rue de Rome. She kept a satin-lined coffin in her bedroom, and occasionally slept in it or lay in it to study her roles, though, contrary to the popular stories, she never took it with her on her travels. She cared for her younger sister who was ill with tuberculosis, and allowed her to sleep in her own bed while she slept in the coffin. She posed in it for photographs, adding to the legends she created about herself.

In April 1880, Bernhardt resigned from the Comédie Française and was proposed to make a theatrical tour of England and then the United States. She could select her repertoire and the cast. She would receive 5,000 francs per performance, 15% of any earnings over 15,000 francs, plus all of her expenses, and an account in her name for 100,000 francs, the amount she owed to the Comédie Française. She accepted immediately.

Bernhardt's first American tour carried her to 157 performances in 51 cities. She travelled on a special train with her own luxurious palace car, which carried her two maids, two cooks, a waiter, her maître d'hôtel, and her personal assistant, Madame Guérard. From New York, she made a side trip to Menlo Park, where she met Thomas Edison, who made a brief recording of her reciting a verse from Phèdre, which has not survived. She crisscrossed the United States and Canada from Montreal and Toronto to Saint Louis and New Orleans, usually performing each evening, and departing immediately after the performance. She gave countless press interviews, and in Boston posed for photos on the back of a dead whale. She performed Phèdre six times and La Dame Aux Camélias 65 times (which Jarrett had renamed "Camille" to make it easier for Americans to pronounce, despite the fact that no character in the play has that name). On 3 May 1881, she gave her final performance of Camélias in New York. Throughout her life, she always insisted on being paid in cash. When Bernhardt returned to France, she brought with her a chest filled with $194,000 in gold coins. She described the result of her trip to her friends: "I crossed the oceans, carrying my dream of art in myself, and the genius of my nation triumphed. I planted the French verb in the heart of a foreign literature, and it is that of which I am most proud."

No crowd greeted Bernhardt when she returned to Paris on 5 May 1881, and theatre managers offered no new roles; the Paris press ignored her tour, and much of the Paris theatre world resented her leaving the most prestigious national theatre to earn a fortune abroad. When no new plays or offers appeared, she went to London for a successful three-week run at the Gaiety Theater. This London tour included the first British performance of La Dame aux Camelias at the Shaftesbury Theatre; her friend, the prince of Wales, persuaded Queen Victoria to authorise the performance. Many years later, she gave a private performance of the play for the queen while she was on holiday in Nice. When she returned to Paris, Bernhardt contrived to make a surprise performance at the annual 14 July patriotic spectacle at the Paris Opera, which was attended by the President of France, and a houseful of dignitaries and celebrities. She recited the Marseillaise, dressed in a white robe with a tricolor banner, and at the end dramatically waved the French flag. The audience gave her a standing ovation, showered her with flowers, and demanded that she recite the song two more times.

With her place in the French theatre world restored, Bernhardt negotiated a contract to perform at the Vaudeville Theatre in Paris for 1500 francs per performance as well as 25 percent of the net profit. She also announced that she would not be available to begin until 1882. She departed on a tour of theatres in the French provinces and then to Italy, Greece, Hungary, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Spain, Austria, and Russia. In Moscow and St. Petersburg, she performed before Czar Alexander III, who broke court protocol and bowed to her. During her tour, she gave performances for King Alfonso XII of Spain, and the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. The only European country where she refused to play was Germany, due to the German annexation of French territory after the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War. Just before the tour began, she met Jacques Damala, who went with her as leading man and then, for eight months, became her first and only husband.

Bernhardt made another world tour, this time to Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Panama, Cuba, and Mexico, then on to Texas, New York City, England, Ireland, and Scotland. She was on tour for 15 months, from early 1886 until late 1887.

In every city she visited, she was feted and cheered by audiences. Emperor Pedro II of Brazil attended all of her performances in Rio de Janeiro and presented her with a gold bracelet with diamonds, which was almost immediately stolen from her hotel. Her performances in every city were sold out, and by the end of the tour, she had earned more than 1 million francs. The tour allowed her to purchase her final home, which she filled with her paintings, plants, souvenirs, and animals.

From then on, whenever she ran short of money (which generally happened every three or four years), she went on tour, performing both her classics and new plays. In 1888, she toured Italy, Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. She returned to Paris in early 1889 with an enormous owl given to her by the Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, the brother of the Czar. Her 1891–92 tour was her most extensive, including much of Europe, Russia, North and South America, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Samoa. Her personal luggage consisted of 45 costume crates for her 15 different productions, and 75 crates for her off-stage clothing, including her 250 pairs of shoes. She carried a trunk for her perfumes, cosmetics and makeup, and another for her sheets and tablecloths and her five pillows. After the tour, she brought back a trunk filled with 3,500,000 francs, but she also suffered a painful injury to her knee when she leaped off the parapet of the Castello Sant' Angelo in La Tosca. The mattress on which she was supposed to land was misplaced, and she landed on the boards.

Despite her successes, her debts continued to mount, reaching two million gold francs by the end of 1898. Bernhardt was preparing to go on another world tour when she learned that a large Paris theater, the Théâtre des Nations on Place du Châtelet, was for lease. The theatre had 1,700 seats, enabling her to pay off the cost of performances more quickly; it had an enormous stage and backstage, allowing her to present several different plays a week; and because it was designed as a concert hall, it had excellent acoustics. On 1 January 1899, she signed a 25-year lease with the City of Paris, though she was already 55 years old.

She renamed it the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, and began to renovate it to suit her needs. The façade was lit by 5,700 electric bulbs, 17 arc lights, and 11 projectors. She completely redecorated the interior. The lobby was decorated with life-sized portraits of her in her more famous roles. Her dressing room was a five-room suite with a huge bathtub that was filled with the flowers she received after each performance and a dining room fitting 12 people, where she entertained guests after the final curtain.

Bernhardt opened the theatre on 21 January 1899 with a revival of Sardou's La Tosca, which she had first performed in 1887. This was followed by revivals of her other major successes, including Phédre, Theodora, Gismonda, and La Dame aux Camélias, plus Octave Feuillet's Dalila, Gaston de Wailly's Patron Bénic, and Rostand's La Samaritaine, a poetic retelling of the story of the Samaritan woman at the well from the Gospel of John. On 20 May, she premiered one of her more famous roles, playing the titular character of Hamlet in a prose adaptation which she had commissioned from Eugène Morand and Marcel Schwob. She played Hamlet in a manner which was direct, natural, and very feminine. Her performance received largely positive reviews in Paris, but mixed reviews in London.

In 1900, Bernhardt presented L'Aiglon, a new play by Rostand. She played the Duc de Reichstadt, the son of Napoleon Bonaparte, imprisoned by his unloving mother and family until his melancholy death in the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. L'Aiglon was a verse drama, six acts long. The 56-year-old actress studied the walk and posture of young cavalry officers and had her hair cut short to impersonate the young Duke. The play was extremely successful; it was especially popular with visitors to the 1900 Paris International Exposition, and ran for nearly a year, with standing-room places selling for as much as 600 gold francs. The play inspired the creation of Bernhardt souvenirs, including statuettes, medallions, fans, perfumes, postcards of her in the role, uniforms and cardboard swords for children, and pastries and cakes; the famed chef Escoffier added Peach Aiglon with Chantilly cream to his repertoire of desserts.

Despite the injury to her leg, she continued to go on tour every summer, when her own theatre in Paris was closed.

In September 1914, Bernhardt discovered that gangrene had developed on her leg, still injured from her 1906 performance in Rio de Janeiro. She was transported to Bordeaux, where on 22 February 1915, a surgeon amputated her leg almost to the hip. She refused the idea of an artificial leg, crutches, or a wheelchair, and instead was usually carried in a palanquin she designed, supported by two long shafts and carried by two men. She had the chair decorated in the Louis XV style, with white sides and gilded trim.

She returned to Paris on 15 October, and, despite the loss of her leg, continued to go on stage at her theatre; scenes were arranged so she could be seated, or supported by a prop with her leg hidden.

On 21 March 1923, she collapsed and never recovered. She died from uremia on the evening of 26 March 1923. Newspaper reports stated she died "peacefully, without suffering, in the arms of her son". At her request, her Funeral Mass was celebrated at the church of Saint-François-de-Sales, which she attended when she was in Paris. The following day, 30,000 people attended her funeral to pay their respects, and an enormous crowd followed her casket from the Church of Saint-Francoise-de-Sales to Pere Lachaise Cemetery, pausing for a moment of silence outside her theatre. The inscription on her tombstone is the name "Bernhardt".

In 1960, Bernhardt was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame with a motion pictures star located at 1751 Vine Street. To date, she is the earliest born person on the Walk (born in 1844), followed by Thomas Edison and Siegmund Lubin.

The Art of the Theatre

In her final years, Bernhardt wrote a textbook on the art of acting. She wrote whenever she had time, usually between productions, and when she was on vacation at Belle-Île. After her death, the writer Marcel Berger, her close friend, found the unfinished manuscript among her belongings in her house on boulevard Pereire. He edited the book, and it was published as L'Art du Théâtre in 1923. An English translation was published in 1925.

Belle-Île

After her 1886–87 tour, Bernhardt recuperated on Belle-Île, a small island off the coast of Brittany, 10 miles south of the Quiberon peninsula. She purchased a ruined 17th-century fortress, located at the end of the island and approached by a drawbridge, and turned it into her holiday retreat. From 1886 to 1922, she spent nearly every summer, the season when her theatre was closed, on Belle-Île. She built bungalows for her son Maurice and her grandchildren, and bungalows with studios for her close friends, the painters Georges Clairin and Louise Abbéma. She also brought her large collection of animals, including several dogs, two horses, a donkey, a hawk given to her by the Russian Grand Duke Alexis, an Andean wildcat, and a boa constrictor she had brought back from her tour of South America. She entertained many visitors at Belle-Île, including King Edward VII, who stopped by the island on a cruise aboard the royal yacht. Always wrapped in white scarves, she played tennis (under house rules that required that she be the winner) and cards, read plays, and created sculptures and ornaments in her studio. When the fishermen of the island suffered a bad season, she organised a benefit performance with leading actors to raise funds for them. She gradually enlarged the estate, purchasing a neighboring hotel and all the land with a view of the property, but in 1922, as her health declined, she abruptly sold it and never returned. During the Second World War, the Germans occupied the island, and in October 1944, before leaving the island, they dynamited most of the compound. All that remains is the original old fort, and a seat cut into the rock where Bernhardt awaited the boat that took her to the mainland.

Vegetarianism

Bernhardt was described as a strict vegetarian (what would later be termed vegan), as she avoided dairy, eggs and meat. Her diet consisted of cereal, fruit, nuts and vegetables.

Books

- Dans les Nuages, Impressions d'une Chaise Charpentier (1878)

- L'Aveu, drame en un acte en prose (1888)

- Adrienne Lecouvreur, drame en six actes (1907)

- Ma Double Vie (1907), & as My Double Life:Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt, (1907) William Heinemann

- Un Coeur d'Homme, pièce en quatre actes (1911)

- Petite Idole (1920; as The Idol of Paris, 1921)

- L'Art du Théâtre: la voix, le geste, la prononciation, etc. (1923; as The art of the Theatre, 1924)

- Sarah Bernhardt My Grandmother (1940)

Roles

- 1862: Racine's Iphigénie in the title rôle, her debut.

- 1862: Eugène Scribe's Valérie

- 1862: Molière's Les Femmes Savantes

- 1864: Labiche & Deslandes, Un Mari qui Lance sa Femme

- 1866: T & H Cognard's La Biche aux Bois

- 1866: Racine's Phèdre (as Aricie)

- 1866: Pierre de Marivaux's Le Jeu de l'Amour et du Hasard (as Silvia)

- 1867: Molière's Les Femmes Savantes (as Armande)

- 1867: George Sand's Le Marquis de Villemer

- 1867: Georges Sand's "François le Champi" (as Mariette)

- 1868: Dumas père Kean (as Anna Damby)

- 1869: Coppée's La Passant, as a male troubador (Zanetto); her first major stage success

- 1870: George Sand's L'Autre

- 1871: Theuriet's Jeanne-Marie

- 1871: Coppée's Fais ce que Dois

- 1871: Foussier and Edmond La Baronne

- 1872: Bouilhet's Mademoiselle Aïssé

- 1872: Hugo's Ruy Blas (as Doña Maira de Neubourg, Queen of Spain)

- 1872: Dumas père Mademoiselle de Belle-Isle (as Gabrielle)

- 1872: Racine's Britannicus (as Junie)

- 1872: Beaumarchais's Le Mariage de Figaro

- 1872: Sandeau's Mademoiselle de la Seiglière

- 1873: Feuillet's Dalila (as Princess Falconieri)

- 1873: Ferrier's Chez l'Avocat

- 1873: Racine's Andromaque

- 1873: Racine's Phèdre (as Aricie)

- 1873: Feuillet's Le Sphinx

- 1874: Voltaire's Zaire

- 1874: Racine's Phèdre (as Phèdre)

- 1875: Bornier's La Fille de Roland

- Dumas fils' L'Étrangère (as Mrs. Clarkson)

- Parodi's Rome Vaincue

- 1877: Hugo's Hernani (as Doña Sol)

- 1879: Racine's Phèdre (as Phèdre)

- 1880: Émile Augier's L'Aventurière

- 1880: Legouvé & Scribe's Adrienne Lecouvreur

- 1880: Meilhac & Halévy's Froufrou

- 1880: Dumas fils' La Dame aux Camélias (as Maguerite)

- 1882: Sardou's Fédora

- Sardou's Théodora (as Theodora, Empress of Byzantium)

- 1887 : La Tosca de Victorien Sardou

- Dumas fils' La Princesse Georges

- 1890: Sardou's Cléopâtre, as Cleopatra

- 1893: Lemaître's Les Rois

- 1894: Sardou's Gismonda

- 1895: Molière's Amphytrion

- 1895: Magda(translation of Sudermann's Heimat)

- 1896: La Dame aux Camélias

- 1896: Musset's Lorenzaccio (as Lorenzino de' Medici)

- 1897: Sardou's Spiritisme

- 1897: Rostand's La Samaritaine

- 1898: Catulle Mendès Medée

- 1898: La Dame aux Camélias (as Marguerite Gautier)

- Barbier's Jeanne d'Arc (as Joan of Arc)

- Morand & Sylvestre's Izéïl (as Izéïl)

- Shakespeare's King Lear (as Cordelia)

- 1899: Shakespeare's Hamlet (as Hamlet)

- Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra (as Cleopatra)

- Shakespeare's Macbeth (as Lady Macbeth) (in French)

- Richepin's Pierrot Assassin (as Pierrot)

- 1900: Rostand's L'Aiglon as L'Aiglon

- 1903: Sardou's La Sorcière

- 1904: Maeterlinck's Pelléas et Mélisande (as Pelléas)

- 1906: Ibsen's The Lady From the Sea

- 1906: Mendès' La Vierge d'Avila (as Saint Theresa)

- 1911: Moreau's Queen Elizabeth (as Queen Elizabeth)

- 1913: Bernard's Jeanne Doré (as Jeanne Doré)

Images for kids

-

Bernhardt as Mary Magdalene, painting by Alfred Stevens (1887)

-

Self-portrait 1910 Fondation Bemberg Toulouse

-

Bernhardt with her bust of Medea in her sculpture studio in Montmartre (c. 1878)

-

Debut of Bernhardt in Les Femmes Savantes at the Comédie Française, 1862

-

Sarah Bernhardt in 1864; age 20, by photographer Félix Nadar

-

Playing Joan of Arc in Jeanne d'Arc by Jules Barbier (1890)

-

Poster for Gismonda by Alphonse Mucha (1894)

-

As Melissande in La Princesse Lointaine by Edmond Rostand (1897)

-

Bernhardt in the role of Phedre at the Hearst Greek Theatre at the University of California, Berkeley (1906)

See also

In Spanish: Sarah Bernhardt para niños

In Spanish: Sarah Bernhardt para niños