Ernest Shackleton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

Ernest Shackleton

|

|

|---|---|

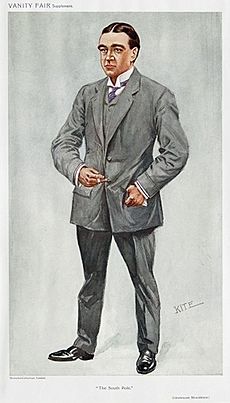

Shackleton in 1904

|

|

| Secretary of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society | |

| In office 11 January 1904 – 10 November 1905 |

|

| Preceded by | Frederick Marshman Bailey |

| Succeeded by | William Lachlan Forbes |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Ernest Henry Shackleton

15 February 1874 Kilkea, County Kildare, Ireland |

| Died | 5 January 1922 (aged 47) Grytviken, South Georgia, Falkland Islands Dependencies |

| Spouse |

Emily Dorman

(m. 1904) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | Kathleen Shackleton (sister) |

| Education | Dulwich College |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Royal Navy, British Army |

| Service years | 1901–1907, 1917–1919 |

| Rank |

|

| Wars | |

Major Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton CVO OBE FRGS FRSGS (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Contents

Early years

Shackleton was born on 15 February 1874, in Kilkea, County Kildare, Ireland. His father, Henry Shackleton, tried to enter the British Army, but his poor health prevented him from doing so. He became a farmer instead, settling in Kilkea. Shackleton's mother, Henrietta Letitia Sophia Gavan, was descended from the Fitzmaurice family. Ernest was the second of their ten children and the first of two sons.

In 1880, when Ernest was six, Henry Shackleton gave up his life as a landowner to study medicine at Trinity College, Dublin (TCD), moving his family to the city. Four years later, the family moved again, from Ireland to Sydenham in suburban London.

From early childhood, Shackleton was a voracious reader, a pursuit which sparked a passion for adventure. He was schooled by a governess until the age of eleven, when he began at Fir Lodge Preparatory School in West Hill, Dulwich, in southeast London. At the age of thirteen, he entered Dulwich College. The young Shackleton did not particularly distinguish himself as a scholar, and was said to be "bored" by his studies.

He was quoted later as saying: "I never learned much geography at school ... Literature, too, consisted in the dissection, the parsing, the analysing of certain passages from our great poets and prose-writers ... teachers should be very careful not to spoil [their pupils'] taste for poetry for all time by making it a task and an imposition." In his final term at the school he was still able to achieve fifth place in his class of thirty-one.

Career

Shackleton's restlessness at school was such that he was allowed to leave at 16 and go to sea. The options available were a Royal Navy cadetship at Britannia, which Shackleton could not afford; the mercantile marine cadet ships Worcester and Conway; or an apprenticeship "before the mast" on a sailing vessel. The third option was chosen. His father was able to secure him a berth with the North Western Shipping Company, aboard the square-rigged sailing ship Hoghton Tower.

During the following four years at sea, Shackleton learned his trade, visiting the far corners of the earth and forming acquaintances with a variety of people from many walks of life, learning to be at home with many kinds of people. Two years later, he had obtained his first mate's ticket, and in 1898, he was certified as a master mariner, qualifying him to command a British ship anywhere in the world.

On 17 February 1901, he was appointed as third officer to the expedition's ship Discovery; on 4 June he was commissioned into the Royal Navy, with the rank of sub-lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve.

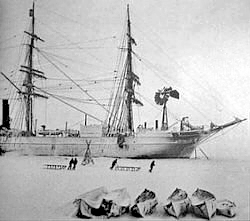

Discovery expedition, 1901–1903

The British National Antarctic Expedition, known as the Discovery expedition after the ship Discovery, was the brainchild of Sir Clements Markham, president of the Royal Geographical Society, and had been many years in preparation. It was led by Robert Falcon Scott, a Royal Navy torpedo lieutenant lately promoted commander, and had objectives that included scientific and geographical discovery.

According to steward Clarence Hare, he was "the most popular of the officers among the crew, being a good mixer". Scott chose Shackleton to accompany Wilson and himself on the expedition's southern journey, a march southwards to achieve the highest possible latitude in the direction of the South Pole. This march was not a serious attempt on the Pole, although the attainment of a high latitude was of great importance to Scott, and the inclusion of Shackleton indicated a high degree of personal trust.

The party set out on 2 November 1902. The march was, Scott wrote later, "a combination of success and failure". A record Farthest South latitude of 82° 17' was reached, beating the previous record established in 1900 by Carsten Borchgrevink. The journey was marred by the poor performance of the dogs, whose food had become tainted, and who rapidly fell sick. All 22 dogs died during the march. The three men all suffered at times from snow blindness, frostbite and, ultimately, scurvy. On the return journey, Shackleton had by his own admission "broken down" and could no longer carry out his share of the work.

On 4 February 1903, the party finally reached the ship. After a medical examination (which proved inconclusive), Scott decided to send Shackleton home on the relief ship Morning, which had arrived in McMurdo Sound in January 1903. Scott wrote: "He ought not to risk further hardship in his present state of health." There is conjecture that Scott's motive for removing him was resentment of Shackleton's popularity, and that ill-health was used as an excuse to get rid of him.

Years after the death of Scott, Wilson and Shackleton, Albert Armitage, the expedition's second-in-command, claimed that there had been a falling-out on the southern journey, and that Scott had told the ship's doctor that "if he does not go back sick he will go back in disgrace." There is no corroboration of Armitage's story.

On 9 April 1904, he married Emily Dorman, with whom he had three children: Raymond, Cecily, and Edward, himself an explorer and later a politician.

Nimrod expedition, 1907–1909

In February 1907, Shackleton presented to the Royal Geographical Society his plans for an Antarctic expedition, the details of which, under the name British Antarctic Expedition, were published in the Royal Geographical Society's newsletter, Geographical Journal. The aim was the conquest of both the geographical South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole. Shackleton then worked hard to persuade others of his wealthy friends and acquaintances to contribute, including Sir Philip Lee Brocklehurst, who subscribed £2,000 (approximately equivalent to £212,000 in 2019) to secure a place on the expedition; author Campbell Mackellar; and Guinness baron Lord Iveagh, whose contribution was secured less than two weeks before the departure of the expedition ship Nimrod.

On 4 August 1907, Shackleton was appointed a Member of the Royal Victorian Order, 4th Class (MVO; the present-day grade of lieutenant).

On 1 January 1908, the Nimrod set off on the British Antarctic Expedition from Lyttelton Harbour, New Zealand. Shackleton's original plans had envisaged using the old Discovery base in McMurdo Sound to launch his attempts on the South Pole and South Magnetic Pole.

The "Great Southern Journey", as Frank Wild called it, began on 29 October 1908. On 9 January 1909, Shackleton and three companions—Wild, Eric Marshall and Jameson Adams—reached a new Farthest South latitude of 88° 23' S, a point only 112 miles (180 km) from the Pole. En route the South Pole party discovered the Beardmore Glacier—named after Shackleton's patron—and became the first persons to see and travel on the South Polar Plateau. Their return journey to McMurdo Sound was a race against starvation, on half-rations for much of the way. At one point, Shackleton gave his one biscuit allotted for the day to the ailing Frank Wild, who wrote in his diary: "All the money that was ever minted would not have bought that biscuit and the remembrance of that sacrifice will never leave me". They arrived at Hut Point just in time to catch the ship.

The expedition's other main accomplishments included the first ascent of Mount Erebus, and the discovery of the approximate location of the South Magnetic Pole, reached on 16 January 1909, by Edgeworth David, Douglas Mawson and Alistair Mackay. Shackleton returned to the United Kingdom as a hero, and soon afterwards published his expedition account, Heart of the Antarctic. Emily Shackleton later recorded: "The only comment he made to me about not reaching the Pole was 'a live donkey is better than a dead lion, isn't it?' and I said 'Yes darling, as far as I am concerned'".

In 1910, Shackleton made a series of three recordings describing the expedition using an Edison phonograph. Several mostly intact cases of whisky and brandy left behind in 1909 were recovered in 2010, for analysis by a distilling company. A revival of the vintage—and since lost—formula for the particular brands found has been offered for sale with a portion of the proceeds to benefit the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust which discovered the lost spirits.

Public hero

On Shackleton's return home, public honours were quickly forthcoming. King Edward VII received him on 10 July and raised him to a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order; in the King's Birthday Honours list in November, he was made a knight, becoming Sir Ernest Shackleton. He was honoured by the Royal Geographical Society, who awarded him a gold medal; a proposal that the medal be smaller than that earlier awarded to Captain Scott was not acted on. All the members of the Nimrod Expedition shore party received silver Polar Medals on 23 November, with Shackleton receiving a clasp to his earlier medal. Shackleton was also appointed a Younger Brother of Trinity House, a significant honour for British mariners.

Besides the official honours, Shackleton's Antarctic feats were greeted in Britain with great enthusiasm. Proposing a toast to the explorer at a lunch given in Shackleton's honour by the Royal Societies Club, Lord Halsbury, a former Lord Chancellor, said: "When one remembers what he had gone through, one does not believe in the supposed degeneration of the British race. One does not believe that we have lost all sense of admiration for courage [and] endurance". The heroism was also claimed by Ireland: the Dublin Evening Telegraph's headline read "South Pole Almost Reached by an Irishman", while the Dublin Express spoke of the "qualities that were his heritage as an Irishman".

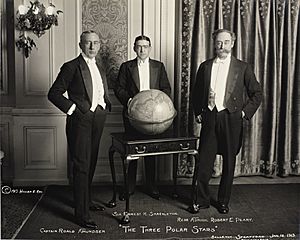

Shackleton's fellow-explorers expressed their admiration; Roald Amundsen wrote, in a letter to RGS Secretary John Scott Keltie, that "the English nation has by this deed of Shackleton's won a victory that can never be surpassed". Fridtjof Nansen sent an effusive private letter to Emily Shackleton, praising the "unique expedition which has been such a complete success in every respect". The reality was that the expedition had left Shackleton deeply in debt, unable to meet the financial guarantees he had given to backers. Despite his efforts, it required government action, in the form of a grant of £20,000 (2008: £1.5 million) to clear the most pressing obligations. It is likely that many debts were not pressed and were written off.

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917

Shackleton published details of his new expedition, grandly titled the "Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition", early in 1914. There is a legend that Shackleton posted an advertisement which emphasised the hardship and danger of the voyage, so that he could better narrow down and select candidates for his expedition, but no record of any such advertisement has survived and its existence is considered doubtful. Two ships would be employed; Endurance would carry the main party into the Weddell Sea, aiming for Vahsel Bay from where a team of six, led by Shackleton, would begin the crossing of the continent. Meanwhile, a second ship, the Aurora, would take a supporting party under Captain Aeneas Mackintosh to McMurdo Sound on the opposite side of the continent. This party would then lay supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier as far as the Beardmore Glacier; these depots would hold the food and fuel that would enable Shackleton's party to complete their journey of 1,800 miles (2,900 km) across the continent.

Shackleton used his considerable fund-raising skills, and the expedition was financed largely by private donations, although the British government gave £10,000 (about £900,000 in 2019 terms).

Disaster struck when his ship, Endurance, was trapped in the ice. They spent 281 days on board waiting for the ice to break again, but the boat was slowly crushed to pieces. Shackleton and his men dragged their lifeboats over many miles of snow and ice to reach sea. They set sail in the lifeboats and eventually reached Elephant Island. In April 1916, Shackleton and four others sailed hundreds of miles to South Georgia to get help at the whaling station there. This was a journey of 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) and took 16 days. Unfortunately the boat he was in landed on the wrong side of the island and they had to climb over the mountainous middle section to reach the whaling station. A rescue party saved everyone from Elephant Island in August 1916.

Final expedition and death

Shackleton returned to the lecture circuit and published his own account of the Endurance expedition, South, in December 1919. In 1920, tired of the lecture circuit, Shackleton began to consider the possibility of a last expedition. He thought seriously of going to the Beaufort Sea area of the Arctic, a largely unexplored region, and raised some interest in this idea from the Canadian government. With funds supplied by former schoolfriend John Quiller Rowett, he acquired a 125-ton Norwegian sealer, named Foca I, which he renamed Quest.

The plan changed; the destination became the Antarctic, and the project was defined by Shackleton as an "oceanographic and sub-antarctic expedition". The goals of the venture were imprecise, but a circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent and investigation of some "lost" sub-Antarctic islands, such as Tuanaki, were mentioned as objectives.

Rowett agreed to finance the entire expedition, which became known as the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition. On 16 September 1921, Shackleton recorded a farewell address on a sound-on-film system created by Harry Grindell Matthews, who claimed it was the first "talking picture" ever made. The expedition left England on 24 September 1921.

Although some of his former crew members had not received all their pay from the Endurance expedition, many of them signed on with their former "Boss". When the party arrived in Rio de Janeiro, Shackleton suffered a suspected heart attack. He refused a proper medical examination, so Quest continued south, and on 4 January 1922, arrived at South Georgia.

In the early hours of the next morning, Shackleton summoned the expedition's physician, Alexander Macklin, to his cabin, complaining of back pains and other discomfort. According to Macklin's own account, Macklin told him he had been overdoing things and should try to "lead a more regular life", to which Shackleton answered: "You are always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to give up?" A few moments later, at 2:50 a.m. on 5 January 1922, Shackleton suffered a fatal heart attack.

Study of diaries kept by Eric Marshall, medical officer to the 1907–09 expedition, suggests that Shackleton suffered from an atrial septal defect ("hole in the heart"), a congenital heart defect, which may have been a cause of his health problems.

Shackleton's will was proven in London on 12 May 1922. Dying heavily in debt, Shackleton's small estate consisted of personal effects to the value of £556 2s. 2d. (equivalent to £21,765 in 2021 ) which he bequeathed to his wife. Lady Shackleton survived her husband by 14 years, dying in 1936.

On 27 November 2011, the ashes of Frank Wild were interred on the right-hand side of Shackleton's gravesite in Grytviken. The inscription on the rough-hewn granite block set to mark the spot reads: "Frank Wild 1873–1939, Shackleton's right-hand man."

Legacy

Early

Before the return of Shackleton's body to South Georgia, there was a memorial service held for him with full military honours at Holy Trinity Church, Montevideo, and on 2 March a service was held at St Paul's Cathedral, London, at which the King and other members of the royal family were represented. Within a year the first biography, The Life of Sir Ernest Shackleton, by Hugh Robert Mill, was published. This book, as well as being a tribute to the explorer, was a practical effort to assist his family; Shackleton died some £40,000 in debt (equivalent to £1,565,495 in 2021 ) A further initiative was the establishment of a Shackleton Memorial Fund, which was used to assist the education of his children and the support of his mother.

During the ensuing decades Shackleton's status as a polar hero was generally outshone by that of Captain Scott, whose polar party had by 1925 been commemorated on more than 30 monuments in Britain alone, including stained glass windows, statues, busts and memorial tablets. A statue of Shackleton designed by Charles Sargeant Jagger was unveiled at the Royal Geographical Society's Kensington headquarters in 1932, but public memorials to Shackleton were relatively few. The printed word saw much more attention given to Scott—a forty-page booklet on Shackleton, published in 1943 by OUP as part of a "Great Exploits" series, is described by cultural historian Stephanie Barczewski as "a lone example of a popular literary treatment of Shackleton in a sea of similar treatments of Scott". This disparity continued into the 1950s.

Later

In 1959, Alfred Lansing's Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage was published. This was the first of a number of books about Shackleton that began to appear, showing him in a highly positive light. At the same time, attitudes towards Scott were gradually changing as a more critical note was sounded in the literature, culminating in Roland Huntford's 1979 treatment of him in his dual biography Scott and Amundsen, described by Barczewski as a "devastating attack". This negative picture of Scott became accepted as the popular truth as the kind of heroism that Scott represented fell victim to the cultural shifts of the late twentieth century. Within a few years, he was thoroughly overtaken in public esteem by Shackleton, whose popularity surged while that of his erstwhile rival declined. In 2002, in a BBC poll conducted to determine the "100 Greatest Britons", Shackleton was ranked 11th while Scott was down in 54th place.

In 1983 the BBC produced and broadcast the miniseries Shackleton, which was released on DVD in 2017. In 2001 Margaret Morrell and Stephanie Capparell presented Shackleton as a model for corporate leadership in their book Shackleton's Way: Leadership Lessons from the Great Antarctic Explorer. They wrote: "Shackleton resonates with executives in today's business world. His people-centred approach to leadership can be a guide to anyone in a position of authority". Other management writers soon followed this lead, using Shackleton as an exemplar for bringing order from chaos. In 2017 Nancy Koehn argued that, in spite of Shackleton's mistakes, financial problems and narcissism, he developed the capability to be successful.

The Centre for Leadership Studies at the University of Exeter offers a course on Shackleton, who also features in the management education programmes of several American universities. In Boston, a "Shackleton School" was set up on "Outward Bound" principles, with the motto "The Journey is Everything". Shackleton has also been cited as a model leader by the US Navy, and in a textbook on Congressional leadership, Peter L Steinke calls Shackleton the archetype of the "nonanxious leader" whose "calm, reflective demeanor becomes the antibiotic warning of the toxicity of reactive behaviour". In 2001, the Athy Heritage Centre-Museum (now the Shackleton Museum), Athy, County Kildare, Ireland, established the Ernest Shackleton Autumn School, which is held annually, to honour the memory of Ernest Shackleton.

Shackleton's death marked the end of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, a period of discovery characterised by journeys of geographical and scientific exploration in a largely unknown continent without any of the benefits of modern travel methods or radio communication. In the preface to his 1922 book The Worst Journey in the World, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, one of Scott's team on the Terra Nova Expedition, wrote: "For a joint scientific and geographical piece of organisation, give me Scott; for a Winter Journey, Wilson; for a dash to the Pole and nothing else, Amundsen: and if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time".

In 1993 Trevor Potts re-enacted the Boat Journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia in honour of Sir Ernest Shackleton, totally unsupported, in a replica of the James Caird. In 2002, Channel 4 in the UK produced Shackleton, a TV serial depicting the 1914 expedition with Kenneth Branagh in the title role. Broadcast in the US on the A&E Network, it won two Emmy Awards.

In a Christie's auction in London in 2011, a biscuit that Shackleton gave "a starving fellow traveller" on the 1907–1909 Nimrod expedition sold for £1250. That same year, on the date of what would have been Shackleton's 137th birthday, Google honoured him with a Google Doodle. Asteroid 289586 Shackleton, discovered by Swiss amateur astronomer Michel Ory in 2005, was named in his memory. The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 10 December 2011 (M.P.C. 77510).

In January 2013, a joint British-Australian team set out to duplicate Shackleton's 1916 trip across the Southern Ocean. Led by explorer and environmental scientist Tim Jarvis, the team was assembled at the request of Alexandra Shackleton, Sir Ernest's granddaughter, who felt the trip would honour her grandfather's legacy. This team became the first to replicate the so-called "double crossing", sailing from Elephant Island to South Georgia and crossing the South Georgian mountains from King Haakon Bay (where Shackleton had landed nearly 100 years prior) to Stromness. The expedition very carefully matched legacy conditions, using a replica of the James Caird (named for the project's patron: the Alexandra Shackleton), period clothing (by Burberry), replica rations (both in calorific content and rough constitution), period navigational aids, and a Thomas Mercer chronometer just as Shackleton had used. This expedition was made into a documentary film, screening as Chasing Shackleton on PBS in the US, and Shackleton: Death or Glory elsewhere on the Discovery Channel.

Also in 2013, a genus of lichen-forming fungi in the Teloschistaceae family was published as Shackletonia by botanists Søchting, Frödén & Arup.

In October 2015, Shackleton's decorations and medals were auctioned; the sale raised £585,000.

In January 2016, Shackleton featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail on the centenary of the Endurance expedition. In August 2016 a statue of Shackleton by Mark Richards was erected in Athy, sponsored by Kildare County Council. In 2017, the musical play Ernest Shackleton Loves Me by Val Vigoda and Joe DiPietro made its debut in New York City at the Tony Kiser Theater, an off-Broadway venue. Blended with a parallel story of a struggling composer, the play retells the adventure of Endurance in detail, incorporating photos and videos of the journey.

Awards and decorations

|

British decorations

|

Other decorations

|

Arms

|

|

See also

In Spanish: Ernest Shackleton para niños

In Spanish: Ernest Shackleton para niños

- Aurora Australis, the first book produced in Antarctica, during the Nimrod Expedition

- Avro Shackleton, British long-range maritime patrol aircraft used by the Royal Air Force, named after him

- RRS Ernest Shackleton, a research ship formerly operated by the British Antarctic Survey

- Shackleton crater, an impact crater near the south pole of the Moon

- Third man factor, refers to the reported situations where an unseen presence such as a "spirit" provided comfort or support during traumatic experiences.