Dutch-language literature facts for kids

Dutch language literature (Nederlandstalige literatuur) includes all the great stories, poems, and plays written in the Dutch language throughout history. Today, about 23 million people speak Dutch. This literature comes from countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname. It also comes from places that used to speak Dutch, like French Flanders and South Africa. Sometimes, writers from other countries who moved to Dutch-speaking areas, like Anne Frank, also wrote in Dutch. In the very beginning, Dutch literature was written in different Dutch dialects. These dialects grew from an old language called Old Frankish.

For a long time, Dutch literature was mostly spoken, not written down, and often in the form of poems. In the 12th and 13th centuries, writers started creating stories about knights and saints for rich noblemen. Later, literature became more about teaching lessons and was written for regular townspeople. Around 1440, groups called rederijkerskamers (Chambers of Rhetoric) formed. These groups, mostly made up of middle-class people, put on plays and performances. Anna Bijns was an important writer from this time. The Reformation, a big religious change, also influenced Dutch literature with new Bible translations. One of the most famous Dutch writers is Joost van den Vondel, a Catholic playwright and poet from the 1600s.

Later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Dutch lands went through many political changes. Important writers included Willem Bilderdijk and Rhijnvis Feith. A new movement called the Tachtigers (meaning "Eighty-ers," from the 1880s) changed Dutch writing. Johan Huizinga was a key historian and writer in the 20th century. During the 1920s, a group of writers, like Nescio, started writing in a simpler style. World War II deeply affected Dutch literature. Writers like Anne Frank and Jan Campert died in concentration camps. After the war, many writers, including Gerard Reve, W.F. Hermans, and Harry Mulisch (often called the "Big Three"), wrote about the harsh realities they had experienced.

Contents

Early Dutch Texts (500–1150)

Around 500 AD, the Old Frankish language slowly changed into Old Dutch. This was a West Germanic language spoken by the Franks and others in their empire. Until the late 11th century, most Dutch literature was spoken poetry. This helped traveling performers remember and recite their stories. Important scientific and religious texts were usually written in Latin. So, very few texts from this early period are still around in Dutch.

In these early times, Old Dutch was quite similar to other West Germanic dialects. This means some old writings can be claimed by both Dutch and German literature. One example is the Wachtendonck Psalms from the 10th century. These were translations of parts of the Bible. Another is the poet Henric van Veldeke from the 12th century.

The Leiden Willeram

The Leiden Willeram is a very old manuscript. It contains a Dutch version of a German book about the Song of Solomon from the Bible. For a long time, people thought it was mostly German with some Dutch parts. But in 1974, a German expert named Willy Sanders showed that it was actually an early attempt to translate the German text into the Dutch spoken in the Netherlands. The writer of the manuscript didn't know some German words, so he made mistakes. This old book was written around the end of the 11th century. It was created in a place called Egmond Abbey in what is now North Holland.

Hebban olla vogala

The oldest known Dutch poem was written by a monk in England around the year 1100. It says: hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan hinase hic enda thu wat unbidan we nu. This means: "All birds have started making nests, except me and you, what are we waiting for." Some experts think it could also be an old English dialect. At that time, Old Dutch and Old English were very much alike.

The Rhinelandic Rhyming Bible

Another important old Dutch text is the Rhinelandic Rhyming Bible. This was a Bible story translated into rhyming verses. We only have parts of it today. It was written in a mix of different old German and Dutch dialects. It was probably made in northwest Germany in the early 12th century.

Middle Dutch Literature (1150–1500)

In the 12th and 13th centuries, writers began to create stories about knights and saints. They wrote these for noblemen who paid them. After the 13th century, literature started to focus more on teaching lessons. It also began to feel more like a national literature for the Dutch people. The main audience was no longer just the rich, but also the growing middle class in towns. Most works from this time were written in the southern parts of the Low Countries, like Brabant and Flanders.

In the early days of Dutch literature, poetry was the most common form. Stories about courtly love and knights were very popular. Henric van Veldeke, mentioned earlier, was the first Dutch writer we know by name. He wrote love poems and long stories about heroes. Many knightly stories were based on older German or French tales. But some were original, like Karel ende Elegast. Another popular type of story was the fable, like the famous Reynard the Fox tale, written by someone known only as Willem.

Until the 13th century, Middle Dutch writings were mostly for nobles and monks. They told stories of knights and religion. But they didn't reach most people. As the 13th century ended, things changed. Towns in Flanders and Holland became rich and powerful. They gained more freedom. With this freedom, a new kind of literature appeared.

The most important writer of this new time was Jacob van Maerlant (around 1235–1300). He was a scholar from Flanders who also worked in Holland. His main works include Der Naturen Bloeme ("The Flower of Nature"), which taught moral lessons, and De Spieghel Historiael ("The Mirror of History"). Van Maerlant is sometimes called the "father of Dutch poetry" because he wrote so much.

Around 1440, literary groups called rederijkerskamers (Chambers of Rhetoric) started. Members were called Rederijkers (Rhetoricians). These groups were usually middle-class. They often put on mystery plays and miracle plays for the public. Their influence grew, and soon no town festival could happen without their support. Their plays often used characters that represented ideas, like "Goodness" or "Greed," and taught moral lessons. Famous examples include Mariken van Nieumeghen ("Mary of Nijmegen") and Elckerlijc (which was translated into English as Everyman).

At the end of this period, Anna Bijns (around 1494–1575) was an important writer. She was a schoolmistress in Antwerp. Her poems often criticized Martin Luther and the Reformation. Her later poems, from 1538, were very strong against the Lutherans. With Anna Bijns's writings, the Middle Dutch period ended, and modern Dutch began.

Renaissance and the Golden Age (1550–1670)

The first signs of the Reformation in Dutch literature appeared around 1540. This was a collection of Psalm translations. For Protestant church services, Jan Utenhove printed Psalms in 1566. He also made the first attempt at a Dutch New Testament translation. The "Gueux songs," sung by the Reformers, were very different. The famous songbook from 1588, Een Geusen Lied Boecxken, was full of brave feelings.

Philips van Marnix (1538–1598) was a key leader in the Dutch war for independence. He was a close friend of William I, Prince of Orange. Many believe he wrote the lyrics to Wilhelmus van Nassouwe, which is now the Dutch national anthem. His main work was Biëncorf der Heilige Roomsche Kercke (Beehive of the Holy Roman Church) from 1569. This book made fun of the Roman Catholic Church. Marnix also worked on a Dutch Bible translation. After he died, others finished it. This translation became the basis for the Statenvertaling (States' Translation). This Bible version included words from all main Dutch dialects. It helped create the modern standard Dutch language.

Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert (1522–1590) was the first true humanist writer in the Low Countries. In 1586, he wrote his great work, Zedekunst ("Art of Ethics"). This was a philosophical book in prose. Coornhert's ideas combined the Bible, ancient Greek writers, and Roman thinkers.

By this time, religious and political unrest led to the Dutch declaring independence from Spain in 1581. This started the Eighty Years' War. As a result, the southern provinces (now Belgium) stayed under Spanish rule. The northern provinces (now the Netherlands) became the Dutch Republic. After the city of Antwerp fell to Spain in 1585, Amsterdam became the new center for writers and thinkers. This led to a cultural boom in the north. In the south, Dutch literature declined, and French became the main language for culture and government.

In Amsterdam, a group of poets and playwrights gathered around Roemer Visscher (1547–1620). This group became known as the Muiderkring ("Circle of Muiden"). Its most famous member was Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft (1581–1647). He wrote poetry and history. From 1628 to 1642, he wrote his masterpiece, the Nederduytsche Historiën ("History of the Netherlands"). Hooft was very careful with his writing style. He is seen as one of the greatest historians of his time. He also greatly helped to standardize the Dutch language. Other members of his group included Visscher's daughter Tesselschade (1594–1649), who wrote poetry, and Gerbrand Adriaensz Bredero (1585–1618), who wrote plays and comedies. Bredero's best-known play is De Spaansche Brabanber Jerolimo, which made fun of refugees from the Spanish south. Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), a diplomat, was also connected to this group. He was known for his clever short poems.

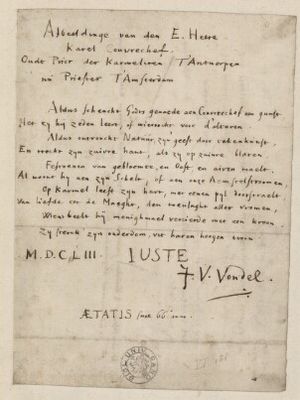

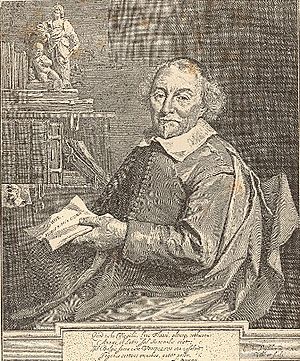

The most famous Dutch writer of all is the Catholic playwright and poet Joost van den Vondel (1587–1679). He mainly wrote plays about history and the Bible. In 1625, he published Palamedes, or Murdered Innocence. This play was a hidden tribute to Johan van Oldebarnevelt, a leader who had been executed. Vondel quickly became the most famous writer in the Netherlands. In 1637, Vondel wrote Gijsbrecht van Aemstel for the opening of a new Amsterdam theater. This play about a local historical figure is still performed today. In 1654, Vondel released what many consider his best work, the tragedy Lucifer. Some say the English poet John Milton got ideas from it. Vondel is seen as a top example of Dutch creativity and intelligence.

Another important group formed in Middelburg, led by Jacob Cats (1577–1660). Cats was very popular for his practical and moralistic poems. His works, like Maechdenplicht ("Duty of Maidens") and Houwelick ("Marriage"), taught lessons about life and family. While some find his writing a bit plain, he was hugely popular with the middle class in the Netherlands.

During this time, poetry and plays were the main types of literature. However, Coornhert wrote philosophy, and Hooft wrote history. Johan van Heemskerk (1597–1656) introduced the romance novel to the Netherlands. In 1637, he wrote Batavische Arcadia, the first original Dutch romance. It was very popular and many writers copied its style.

The period from 1600 to 1650 was a golden age for Dutch literature. Many great writers became known, and writing reached its peak. Three very talented writers, Vondel, Cats, and Huygens, lived to be very old. Under their influence, a new generation of writers continued this great tradition until around 1670, when Dutch literature started to decline.

Later Years (1670–1795)

After the Low Countries officially split into the Dutch Republic and the Spanish Netherlands in 1648, "Dutch literature" mostly meant writing from the Republic. The Dutch language became less popular in the southern parts. One important exception was Michiel de Swaen (1654–1707) from Dunkirk. He wrote comedies, moral plays, and religious poetry. When Dunkirk became French territory, De Swaen became the first important French-Flemish writer.

Playwrights of this time often copied French styles. Jan Luyken (1649–1712) was a well-known poet. Justus van Effen (1684–1735) helped bring new interest to literature. He was influenced by French refugees who came to the Republic. Van Effen wrote mostly in French for a while. But after visiting London, he started his Hollandsche Spectator ("Dutch Spectator") magazine in 1731. This magazine was very important for Dutch literature in the mid-18th century.

The year 1777 was a turning point. That year, Elizabeth “Betje” Wolff (1738–1804) and Agatha “Aagje” Deken (1741–1804) decided to live and write together. In 1782, they published their first novel, Sara Burgerhart, which was very popular. They wrote two more novels. The end of the 18th century saw a general rise in new ideas. German romanticism greatly influenced Dutch literature. German poetry replaced French classical styles, even as France expanded its power into the Netherlands.

The 19th Century

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were a time of big political changes in the Low Countries. The southern parts were taken over by France. The Dutch Republic also became a French-controlled state before being fully annexed by France in 1810. After Napoleon's defeat, the northern and southern provinces were briefly united as the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. But this only lasted until 1830, when the southern provinces broke away to form Belgium. These changes had little effect on literature. In Belgium, French remained the main language for government and education.

In this changing world, Willem Bilderdijk (1756–1831) was a very important writer. He was smart but also a bit unusual. He wrote many poems. Bilderdijk didn't like the new romantic style of poetry. But this style still came to the Netherlands. Hiëronymus van Alphen (1746–1803) is best known for his children's poems. Rhijnvis Feith (1753–1824) wrote sad, romantic stories.

Hendrik Tollens (1780–1856) combined some of Bilderdijk's power with Feith's gentle style. Tollens wrote patriotic poems and songs about great moments in Dutch history. His poem "Wien Neêrlands Bloed" was the Dutch national anthem until 1932. A. C. W. Staring (1767–1840) was another talented poet. His poems mixed romantic and rational ideas.

The Dutch language in the north grew stronger and richer for writing. However, no truly great writers appeared in the Netherlands for about 30 to 40 years before 1880. Dutch writers often stuck to old ways of writing.

Poetry and much of the prose were dominated by writers who were or had been Calvinist ministers. So, many of their works focused on Bible stories and middle-class family values. Nicolaas Beets (1814–1903) is a good example. He wrote many sermons and poems. But he is best remembered for his funny stories about Dutch life in Camera Obscura (1839). He wrote these as a student under the name Hildebrand.

The talented poet P.A. de Genestet (1829–1861) died young. His narrative poem "De Sint-Nicolaasavond" ("Eve of Sinterklaas") came out in 1849. Piet Paaltjens (François Haverschmidt, 1835–1894) is considered one of the few readable 19th-century poets. He showed the true romantic style, like the German poet Heinrich Heine.

In Belgium, writers began to value their Flemish heritage. They pushed for the Dutch language to be recognized. Charles De Coster wrote historical romances about the Flemish past, but in French. Hendrik Conscience (1812–1883) was the first to write about Flemish topics in Dutch. He is seen as the father of modern Flemish literature. In Flemish poetry, Guido Gezelle (1830–1899) was important. He celebrated his faith and Flemish roots using old Flemish words.

After the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) became part of the Dutch state again in 1815, literature continued to be written there. As people became more aware of how the colonies were run, a powerful voice emerged: Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker, 1820–1887). His book Max Havelaar (1860) strongly criticized how the colonies were managed. It is one of the few 19th-century prose works still widely read today.

Conrad Busken-Huet (1826–1886) was a leading literary critic. He defended Dutch literature as he understood it. He saw that a big change was coming in literature, but he didn't fully understand it. Still, his dedication and knowledge were respected.

In November 1881, Jacques Perk (born 1860) died. After his death, his poems, especially a series of sonnets called Mathilde, were published in 1882. They caused a huge stir. Perk had rejected old, formal poetry styles and broken traditional rhythms. His music was new to the Netherlands. A group of young men gathered around his name. They were joined by Marcellus Emants (1848–1923), who wrote a symbolic poem called "Lilith" in 1879. Emants later published a paper in 1881 that openly attacked the old style of writing.

Next came Willem Kloos (1857–1938). He had been Perk's editor and friend. Kloos led the new movement. His strong attacks on accepted ideas about beauty caused a scandal. For a while, the new poets and critics found it hard to be heard. But in 1884, they started a magazine called De Nieuwe Gids ("The New Guide"). This allowed them to directly challenge the old writers. The new movement was called Tachtigers or "Movement of (Eighteen-)Eighty." The Tachtigers believed that writing style must match the content. They felt that deep emotions could only be shown with a raw and personal writing style. They were influenced by English poets like Percy Bysshe Shelley and French naturalists.

Leading writers of the Tachtigers included:

- Willem Kloos

- Albert Verwey

- Frederik van Eeden

- Marcellus Emants

- Lodewijk van Deyssel

- Herman Gorter

Around the same time, Louis Couperus (1863–1923) appeared. He spent his childhood in Java (Indonesia) and kept a certain "tropical" richness in his writing. His first works were poems in the Tachtigers style. But Couperus became much more important as a novelist. In 1891, he published Noodlot, which was translated as Footsteps of Fate. Oscar Wilde greatly admired it. Couperus continued to write important novels until his death in 1923. Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932) also showed talent for prose in De kleine Johannes ("Little Johnny", 1887) and Van de koele meren des doods ("From the Cold Pools of Death", 1901), a sad novel.

After 1887, modern Dutch literature stayed somewhat the same. By the end of the 19th century, it was actually declining. In 1889, a new poet, Herman Gorter (1864–1927), published a long poem called Mei ("May"). It was unusual in its rhythm and style. Kloos collected his poems in 1894. Other writers, except Couperus, seemed to write less. Once the Tachtigers had won recognition, they seemed to rest on their success and just repeated their old ideas.

The main playwright at the end of the century was Herman Heijermans (1864–1924). He wrote very realistic plays, often with social messages. He single-handedly brought Dutch theater into modern times. His play about fishermen, Op Hoop van Zegen ("Trusting Our Fate in the Hands of God"), is still performed today and is his most popular work.

The 20th Century

Like the rest of Europe, the Netherlands remained largely unchanged from the 19th century until World War I (1914–1918). Belgium was invaded by Germany. The Netherlands faced serious money problems because it stayed neutral and was isolated between the warring sides.

After the war, both Belgian and Dutch societies became "pillarised." This meant that major religious and political groups (Protestant, Catholic, Socialist, and Liberal) had their own newspapers, magazines, schools, and TV stations. Writers often gathered around the literary magazines of these different "pillars."

One of the most important historical writers of the 20th century was Johan Huizinga. His books are known around the world and have been translated into many languages. His writing was influenced by the literary figures of the early 20th century.

Other important writers from this period include:

- Hendrik Marsman

- Adriaan Roland Holst

- J. van Oudshoorn

- Arthur van Schendel

- Hendrik de Vries

- Jacobus van Looy

New Objectivity and the Forum Group (1925–1940)

In the 1920s, a new group of writers appeared. They moved away from the fancy style of the 1880s movement. They felt the old style was too focused on the self and not connected to real life. Their movement was called "Nieuwe Zakelijkheid," or New Objectivity. Nescio (J.H.F. Grönloh, 1882–1961) was an early example, publishing short stories in the 1910s. F. Bordewijk (1884–1965) is a great example of New Objectivity. His short story Bint (1931) shows this clear, concise writing style.

A part of the New Objectivity movement centered around the Forum magazine. This magazine was published from 1932 to 1935. It was edited by Menno ter Braak (1902–1940), a leading literary critic, and the novelist Edgar du Perron (1899–1940). Writers linked to this modern magazine included Willem Elsschot and Marnix Gijsen from Belgium, and J. Slauerhoff and Simon Vestdijk from the Netherlands.

Second World War and Occupation (1940–1945)

World War II brought a sudden change to Dutch literature. At the start of the German occupation, Du Perron died from a heart attack, Ter Braak died, and Marsman drowned trying to escape. Many other writers had to hide or were sent to Nazi concentration camps, like Vestdijk. Many writers stopped publishing because they refused to join the German-controlled Kultuurkamer (Chamber of Culture). This group wanted to control all cultural life in the Netherlands. The young writer Anne Frank, whose diary was published after her death, died in a German concentration camp. So did Jan Campert, a crime writer and poet. He was arrested for helping Jewish people and died in 1943. His poem De achttien dooden ("The eighteen dead") is about a captured resistance member waiting to be executed. It became the most famous Dutch war poem.

Modern Times (1945–Present)

Writers who lived through the horrors of World War II wrote about how their view of reality had changed. Many looked back on their experiences, just like Anne Frank did in her diary. This was true for Het bittere kruid (The bitter herb) by Marga Minco, and Kinderjaren (Childhood) by Jona Oberski. A new style, called "shocking realism," became popular. It is mostly linked to three authors: Gerard Reve, W.F. Hermans, and Anna Blaman. Their writing showed raw reality and human cruelty, focusing on physical details. An example is "De Avonden" (The evenings) by Gerard Reve. It describes a teenager's disappointment during the "wederopbouw," the period of rebuilding after the war. In Flanders, Louis Paul Boon and Hugo Claus were key writers of this new style.

Important writers from modern times include:

- Netherlands: Lucebert, Hans Lodeizen, Jules Deelder, J. Bernlef, Remco Campert, Hella S. Haasse, Harry Mulisch, Willem Frederik Hermans, Gerard Reve, Jan Wolkers, Cees Nooteboom, Arnon Grunberg, Joost Zwagerman.

- Flanders: Louis Paul Boon, Hugo Claus, Jef Geeraerts, Tom Lanoye, Erwin Mortier, Dimitri Verhulst, Herman Brusselmans.

- Suriname: Hugo Pos, Corly Verlooghen, Ellen Ombre.

See also

In Spanish: Literatura neerlandesa para niños

In Spanish: Literatura neerlandesa para niños

- Middle Dutch literature

- Dutch folklore

- Canon of Dutch Literature

- Dutch Indies literature

- Belgian literature

- Afrikaans literature

- List of Dutch language writers

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |