Hipólito Yrigoyen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hipólito Yrigoyen

|

|

|---|---|

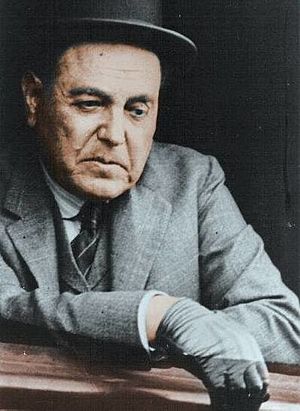

Yrigoyen c. 1926

|

|

| President of Argentina | |

| In office 12 October 1928 – 6 September 1930 |

|

| Vice President | Enrique Martínez |

| Preceded by | Marcelo T. de Alvear |

| Succeeded by | José Félix Uriburu |

| In office 12 October 1916 – 11 October 1922 |

|

| Vice President | Pelagio Luna |

| Preceded by | Victorino de la Plaza |

| Succeeded by | Marcelo T. de Alvear |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 July 1852 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Died | 3 July 1933 (aged 80) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery |

| Political party | Radical Civic Union (1891-1933) |

| Other political affiliations |

Civic Union (1890-1891) |

| Profession | Lawyer, teacher |

| Signature |  |

Hipólito Yrigoyen (born July 12, 1852 – died July 3, 1933) was an important Argentine politician. He served as President of Argentina two times. His first term was from 1916 to 1922, and his second was from 1928 to 1930. He was the first president chosen by a truly democratic vote. This happened thanks to the Sáenz Peña Law of 1912, which made voting secret and mandatory for men. Yrigoyen worked hard to make this law happen.

People called him "the father of the poor." During his time as president, the lives of working-class people in Argentina got better. He helped pass laws that improved factory conditions and working hours. He also introduced public education that everyone could access. Yrigoyen was a nationalist president. This meant he believed Argentina should control its own money, transportation, and energy resources like oil.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Hipólito Yrigoyen was born in Buenos Aires on July 12, 1852. His father, Martín Yrigoyen Dodagaray, was an immigrant from France. His mother was Marcelina Alén Ponce. He had four siblings.

When he was nine, Yrigoyen went to the San José of Buenos Aires School. He later studied at the School of South America, where his uncle, Leandro N. Alem, taught philosophy. Yrigoyen was a quiet student. He first thought about becoming a priest but then decided to study law.

At age fifteen, he paused his studies to help his father. His father owned trolleys that worked at the port. Yrigoyen also worked in a store and on the trolleys. He gained a lot of different work experiences when he was young. In 1867, he worked in a law office shared by his uncle and Aristóbulo del Valle.

Yrigoyen's last name, "Yrigoyen," comes from the Basque word "Hirigoyen," which means "city of the high." He sometimes used "Irigoyen" and "Yrigoyen" interchangeably.

Early Political Career

After finishing school in 1869, Yrigoyen started his political life. He joined the Autonomist Party with his uncle, Leandro N. Alem. This party wanted free voting and changes to the justice system.

In 1872, when he was twenty, Yrigoyen became a Police Commissioner in Balvanera. This was thanks to his uncle's influence. He continued his law studies. In 1874, he took part in a revolution led by Bartolomé Mitre. In 1877, Yrigoyen, Alem, and Aristóbulo del Valle formed the Republican Party. Yrigoyen was removed from his police job that same year.

In 1878, he was elected as a Provincial Deputy for the Republican Party. His term ended in 1880 when Buenos Aires became a federal city. Yrigoyen was then elected to the National Congress. This was the first time he disagreed with his uncle Alem, who was against the new law. Yrigoyen finished his law studies in 1878 and officially became a lawyer three years later.

He started teaching history, civic instruction, and philosophy in 1880. He taught for about 24 years. He was removed from his teaching job in 1905 because he led a revolution. Even though he didn't earn much, he gave his salary to the Children's Hospital. He let his students lead classes while he observed.

During the 1880s, Yrigoyen became very wealthy from farming. He bought and rented large farms (estancias) in different provinces. He raised cattle to sell. This work helped him understand the problems of people in the countryside. He used most of his money to fund his political activities. He even went into debt by the time he died.

Yrigoyen lived simply on his farms. He worked alongside his employees and advised them to buy small properties for their future. His workers received higher salaries and a share of the profits.

In 1890, the Civic Union party was formed. Yrigoyen joined and helped plan the Revolution of the Park. He became the Chief of Police for the temporary government. However, the revolution was stopped. The Civic Union then split into two parties in 1891. One was the National Civic Union, and the other was the Radical Civic Union (UCR), led by Alem. Yrigoyen became the head of the Radical Committee in Buenos Aires Province.

Armed Rebellion

In 1892, Luis Sáenz Peña became President. Many radical leaders, including Alem, were arrested. Yrigoyen was one of the few who was not. In November 1892, the Radical Civic Union called for an armed uprising against the government.

On July 29, 1893, a revolution began in San Luis Province. On July 31, the city of Rosario was taken. Yrigoyen started his own plan in Buenos Aires. He gathered about 60 people at his farm and took the Las Flores police station. On August 3, he arrived in Temperley with 1,200 men. The camp grew to 2,800 armed citizens.

On August 4, the governor resigned. Two days later, Yrigoyen was asked to be the temporary governor, but he refused. He said he fought to end an illegal government, not to start another one.

On August 8, Yrigoyen's brother, Martín Yrigoyen, led 3,500 civilians to take La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires Province. The Yrigoyen brothers marched at the front of the troops. A temporary government was formed, but it lasted only nine days. The national government sent troops to stop the revolution. On August 25, the Radical Committee announced they would stop fighting.

Yrigoyen disagreed with Alem, who wanted to continue the uprising. This caused problems between them. In October, the revolution was completely defeated. Yrigoyen was arrested for the first time in his life. He was held on a boat with other prisoners and then sent to Montevideo, Uruguay. He stayed there until December.

Yrigoyen met Marcelo T. Alvear during this time. Alvear was a fellow radical leader. In 1897, Yrigoyen had a fencing duel with Lisandro de la Torre. Alvear taught Yrigoyen how to fence, and Yrigoyen won the duel. He continued to practice fencing even when he was in his 70s.

On July 1, 1896, Leandro Alem died. Aristóbulo del Valle also died earlier that year. This left Yrigoyen as the main leader of the Radical Civic Union.

Revolution of 1905

In February 1905, a new radical revolution began. The government suspected a conspiracy and arrested many people. Revolts happened in Bahía Blanca, Mendoza, Córdoba, and Rosario. However, the capital, Buenos Aires, remained under government control.

In Mendoza, the governor was removed, and José Néstor Lencinas took over. In Córdoba, Delfor Del Valle led an infantry that tried to capture Vice President José Figueroa Alcorta and other government leaders. Many revolutionary leaders escaped to Chile or Uruguay, but some were captured. About 70 prisoners were held on a naval ship in poor conditions. They were quickly tried and sent to a prison in Ushuaia.

Yrigoyen stayed hidden during the uprising. He was supposed to appear in Federal Court, but he did not. The government later cleared him of charges. Yrigoyen used his wealth from his farms to support the exiled leaders. After the revolution, he worked to free the imprisoned revolutionaries.

President Manuel Quintana, who was against freeing the prisoners, died in March 1906. José Figueroa Alcorta became president and passed a law that freed the prisoners. Yrigoyen met with President Figueroa Alcorta in 1907 and 1908. He tried to convince him to hold fair elections, but he had little success.

In the 1910 presidential elections, Roque Sáenz Peña became the candidate for the National Autonomist Party. Sáenz Peña wanted to create an election system that would stop fraud. He was a friend of Yrigoyen and had co-founded the Republican Party with him years before.

Path to Electoral Reform

The political changes began when Roque Sáenz Peña became president. He worked hard to pass a law that would ensure secret, universal, and mandatory elections for all male citizens. This law became known as the Sáenz Peña Law. It was passed on February 10, 1912.

This law was very important because it allowed for truly fair elections. Before this, elections were often unfair. The new law applied to national elections, like for president and vice-president. In 1912, the governor of Santa Fe was replaced, and new elections were held under the new law. The Radical Civic Union participated and won, bringing Manuel Menchaca to power. He was the first Argentine governor elected in secret elections.

In March 1916, the Radical Civic Union met to choose their candidates for president and vice-president. Yrigoyen was expected to win the nomination easily, but he did not want to accept it. The delegates had to convince him. Finally, Yrigoyen accepted the candidacy. Pelagio Luna was chosen as his vice-presidential candidate.

Presidential Elections of 1916

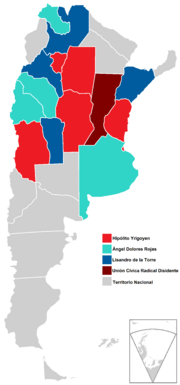

The presidential elections on April 2, 1916, were the first to use the Sáenz Peña Law. This law made voting secret and mandatory for men. Because of this, it is considered the first truly democratic election in Argentina's history. (Later, in 1951, women also gained the right to vote, making elections fully democratic).

The results surprised many. Radical and socialist voters turned out across the country. The old political parties struggled to form a strong opposition. The Hipólito Yrigoyen and Pelagio Luna team won the popular vote with 339,332 votes. The Conservative Party received 153,406 votes. Yrigoyen also won in the Electoral College.

After taking his oath, Yrigoyen was carried by a huge crowd of people from the Congress building to the Casa Rosada (the government palace). There was no security detail. This showed how much support he had from the people.

Yrigoyen had suggested to the previous president, Figueroa Alcorta, to intervene in provinces where fraud was still common. These "federal interventions" were done to ensure fair elections. In many areas, radical candidates won. In other provinces, like Corrientes and San Luis, conservatives won, and their victories were respected.

Yrigoyen's victory meant that, for the first time, middle-class people without strong economic ties to the upper classes were working in government. This was a big change. In his early years as president, Yrigoyen often used decrees to pass laws because the conservatives still had a majority in the Senate. After the 1918 elections, the Radical Civic Union gained a majority in the lower house of Congress.

Yrigoyen believed that the Radical Civic Union was not just a party but "a motherland itself." He saw himself as an "apostle" working for the "liberation of Argentina."

First Presidency (1916–1922)

Yrigoyen was the first president to have a strong nationalist view. He believed Argentina should control its own money, credit, transportation, energy, and oil. He planned to create a Central Bank to manage foreign trade. He also founded the energy company YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales) to control oil. He put strict rules on foreign companies that managed Argentina's railroads.

He also defended Argentina's independence in foreign policy. For example, when the United States intervened in the Dominican Republic, Yrigoyen ordered Argentine war boats to fly the Dominican Republic's flag.

Yrigoyen put strict controls on British-owned railways in Argentina. He also supported State Railways, hoping to connect Argentina to the Pacific Ocean. This would help transport goods from the northwest and southwest of the country to Perú, Chile, and Bolivia.

He used federal intervention in the provinces many times. This caused conflicts with conservative groups. He argued that governors elected before the new voting law were not legitimate.

Many reforms were made during his first presidency. A law was passed in 1918 to set minimum wages for homeworkers. In 1919, a law helped build affordable houses for workers. In 1921, a law limited rent increases. A homestead law in 1917 gave public land to farmers in the far north and south. The National Mortgage Bank helped landless farmers buy rural property.

A law in 1921 set rules for rental contracts and working conditions for tenants. Railroad workers also got pension plans. A law in 1921 banned matches with white or yellow phosphorus. More than 3,000 new schools were opened, and the government fought against illiteracy. They also helped set up a consumer cooperative for state railway employees. A decree was signed about the work of women and children, making sure stores had enough chairs for female workers. In 1921, a fund was created for old age, disability, and survivor pensions for public utility workers. Public health improved, with new water and sewage systems in towns.

Economic Policy

Argentina's economy grew a lot during Yrigoyen's time, with an average growth of 8.1% per year. This was one of the best periods of economic growth in the country's history. Yrigoyen had to deal with problems from World War I. Argentina remained neutral, which meant it continued to supply goods to its allies and customers. Exports of blankets and canned meat tripled between 1914 and 1920.

Because Europe was focused on war, fewer manufactured goods were imported. This led to new industries in Argentina that produced these goods. Trade with the United States grew between 1914 and 1921.

When the war started, the previous president had stopped the exchange of gold for paper money to prevent money from leaving the country. This helped the Argentine currency stay strong. By the end of Yrigoyen's first term, the Argentine peso was backed by 80% gold. The government tried to create a Bank of the Republic in 1917 to regulate the economy, but it did not succeed. Yrigoyen reduced the country's foreign debt.

In 1919, Congress passed rules for solving worker conflicts. A committee was set up to help workers and employers reach agreements. Also in 1919, a law was proposed to improve the inhumane working conditions for yerba mate producers. This law was passed later in 1925 but was vetoed by Marcelo T. de Alvear.

Towards the end of this period, international prices for Argentina's goods began to fall, while prices for imported manufactured goods increased. This led to an economic crisis that became part of the global economic crisis in 1929.

Second Presidency (1928–1930)

After Marcelo T. de Alvear's term ended in 1928, Yrigoyen was overwhelmingly elected President for a second time. In December 1928, U.S. President-elect Herbert Hoover visited Argentina. He met with Yrigoyen to discuss trade. There was an attempt to assassinate Hoover, but the person was arrested. President Yrigoyen personally made sure Hoover was safe until he left the country.

During his second presidency, more reforms were introduced. On June 12, 1929, Yrigoyen signed a decree to spend money on building primary schools in Buenos Aires and other areas. A law passed on August 29, 1929, set working hours at 8 hours a day and 48 hours a week for all salaried employees and workers. A new office was added to the Ministry of Agriculture to provide information about agricultural lands, like prices and distances from markets.

Yrigoyen was in his late seventies during his second term. His aides sometimes hid news about the Great Depression, which started in late 1929. On December 24, 1929, he survived an assassination attempt.

Some groups in the army and the Standard Oil company openly planned to overthrow him. Standard Oil was against Yrigoyen's efforts to stop oil smuggling and against the existence of the state-owned YPF oil company. On September 6, 1930, Yrigoyen was removed from power in a military coup led by General José Félix Uriburu. This was the first military coup in Argentina since the country's constitution was adopted. After the coup, some of Yrigoyen's ministers and allies were arrested by the new government but were later released.

Later Life and Death

After being overthrown, Yrigoyen was placed under house arrest. He was also confined several times to Martín García Island. Hipólito Yrigoyen died in Buenos Aires on July 3, 1933. He was buried in La Recoleta Cemetery.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Hipólito Yrigoyen para niños

In Spanish: Hipólito Yrigoyen para niños