St Mary's Church, Reculver facts for kids

St Mary's Church at Reculver was built way back in the 7th century. It started as a special church or monastery on the site of an old Roman fort in Kent, England. In 669, King Ecgberht of Kent gave the land to a priest named Bassa to build this church. It became very important to the Kentish kings, and King Eadberht II was even buried there in the 760s. By the early 800s, the church was very rich.

Over the next few centuries, different kings and archbishops fought over who controlled the church. Viking attacks might have caused the religious community to leave in the 800s. But by the early 1000s, it was run by a dean and monks again. By 1086, when the Domesday Book was written, St Mary's was serving as a local parish church for the area.

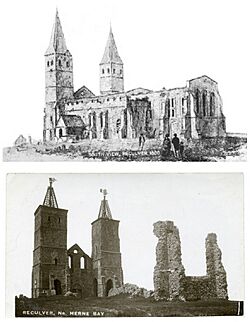

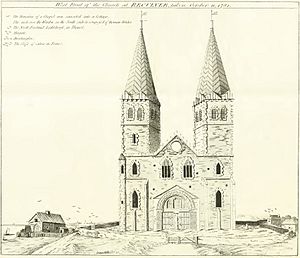

The first church building used stones and tiles from the old Roman fort. It was simple, with a main hall (nave) and a rounded end (apse) for the altar. It also had small rooms (porticus) on the sides. The church was made much bigger over the Middle Ages. Twin towers were added in the 1100s, and porches were added in the 1400s. Reculver was a busy place for a long time, but then it started to decline. The church began to fall apart, and the coastline nearby was eroding. In 1809, most of the church was torn down.

Luckily, in 1810, a group called Trinity House saved the church's remains. The towers were important landmarks for ships, so they protected them. Some parts of the old church were used to build a new church nearby. Other parts were used for a new harbor wall in Margate. Some amazing pieces from the original church still exist, like parts of a tall stone cross and two stone columns from an arch. These pieces are now kept at Canterbury Cathedral. They show how special the Anglo-Saxon architecture and art of the church were.

Contents

How the Church Began

The first church at Reculver was started in 669. King Ecgberht of Kent gave land to a priest named Bassa for this purpose. This was a big event. Some historians think the king wanted to create a strong English church here. This might have balanced the power of the Canterbury Church, which had many leaders from other countries.

Historians sometimes call the church a "minster" and sometimes a "monastery." A minster was a church with a group of clergy (like priests) who served a large area. A monastery was a place where monks lived and prayed. In early England, the difference between these was not always clear. The word "monasterium" (Latin for monastery) could mean a church served by a group of clergy, just like a minster. By the 800s, the religious groups at Kentish monasteries were definitely made up of priests and other clergy.

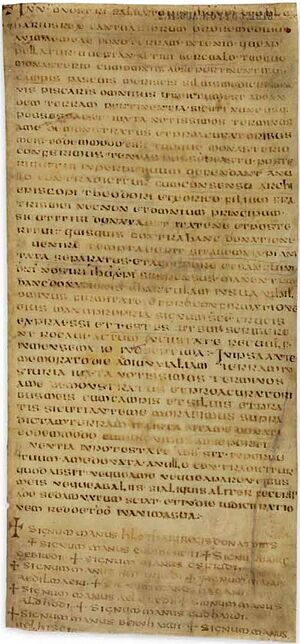

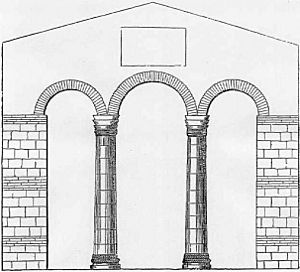

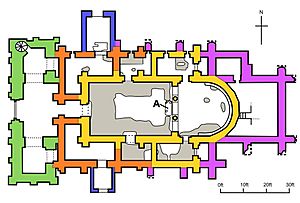

The church was built inside the ruins of an old Roman fort called Regulbium. This was common in Anglo-Saxon England. People often reused Roman walls for important churches. The new church was built almost entirely from stones and tiles taken from the Roman fort. It had a main hall (nave) and a rounded end (chancel or apse). A triple arch, made of two limestone columns from France, separated the nave from the chancel. Roman tiles were used for the arches. These columns were new, not Roman, and showed influences from other parts of Europe. Inside the apse, there was a stone bench. Two small rooms, called porticus, were built on the north and south sides where the nave met the chancel. These rooms were like early transepts. The church walls were covered with plaster inside and out, making them look plain.

Ten years after the church was founded, in 679, King Hlothhere of Kent gave land to Abbot Berhtwald and his "monastery" at Reculver. This land included Sturry and Sarre. Sarre was a very important place because it overlooked where two rivers met. It was also linked to Canterbury. In the 760s, Sarre had a toll-station where the Kentish kings collected money from trading ships. Giving Sarre to Reculver showed how much the king favored the church. The church probably got a share of the tolls.

In the old document from 679, Reculver is called a civitas, or city. This probably referred to its Roman past or its church status, not a large town. In 692, Reculver's abbot, Berhtwald, became the Archbishop of Canterbury. He likely helped Reculver a lot from this powerful position.

More documents show that Reculver continued to get gifts from Kentish kings in the 700s. It gained land and was excused from some tolls. King Eadberht II of Kent was buried in the church in the 760s. Other records mention properties belonging to Reculver, like land in Higham and a place called Dunwaling land. These records also name other abbots of Reculver, showing a long line of leaders.

By the early 800s, the monastery was "extremely wealthy." But from then on, it was often treated like property. For much of the time from 764 to 825, Kent was controlled by the kings of Mercia. King Offa of Mercia (757–796) might have taken direct control of Reculver. In 811, Archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury seemed to control the monastery, but then King Coenwulf of Mercia (796–821) took it. Coenwulf had permission from the Pope to control monasteries in England.

A big fight started in 817 between Archbishop Wulfred and King Coenwulf over who controlled monasteries, especially Reculver. The dispute lasted until 821, when Wulfred had to give up a lot of land and pay a huge fine to get Reculver back. Even after that, Coenwulf's heir, Cwoenthryth, continued to deny Wulfred control until a final agreement was reached in 825.

From 825, the kings of Wessex controlled Kent. A new agreement was made in 838, recognizing the kings as protectors of monasteries. This change might have happened because Viking attacks were becoming more frequent. Vikings started attacking Kent in the late 700s. They spent winters on the Isle of Thanet and the Isle of Sheppey. Reculver was on the coast, making it an easy target for Vikings looking for treasure.

By the 900s, Reculver was no longer a major church in Kent. It was controlled only by the kings of Wessex. In 949, King Eadred of England gave Reculver back to the archbishops of Canterbury. At this time, the church's land included Hoath, Herne, Sarre, and Chilmington.

From Monastery to Local Church

Reculver might have had a religious community into the 900s, even with Viking attacks. It's possible the abbot and community moved to Canterbury for safety. A monk from Reculver named Ymar was later called a saint. He was probably killed by Vikings in the 900s and seen as a martyr. By the 1000s, the monastery had "dropped out of sight." The last abbot recorded was Wenredus. Around 1030, the church was led by a dean named Givehard and had monks, some of whom were from Europe. This might have been a temporary return of community life.

By 1066, the monastery had become a parish church, serving the local community. In 1086, the Domesday Book listed Reculver as belonging to the Archbishop of Canterbury. William the Conqueror had given it back to the archbishop when he died in 1087. The value of the Reculver estate grew a lot between 1066 and 1086. The Domesday record for Reculver included farmland, a mill, salt pans, a fishery, and many villagers. These numbers suggest a population of hundreds of people living on the estate.

By the 1200s, Reculver parish was very rich, which led to arguments over its control. In 1291, a church survey showed the total income for the rector and vicar of Reculver was about £130. The parish included smaller chapels in St Nicholas-at-Wade, Shuart, Hoath, and Herne. In 1310, Archbishop Robert Winchelsey divided the parish. He created new parishes from Reculver's chapels because they were so far away and the population had grown to over 3,000 people. It was hard for people to travel to Reculver for services and burials. Shuart became part of St Nicholas-at-Wade parish and its church was later torn down. However, St Mary's Church, Reculver, still received payments from Herne and St Nicholas-at-Wade parishes for many years as a sign of its original importance.

Growing Bigger and Then Shrinking

Church Enlargement

The church building was made much larger over time. In the 700s, the outer walls of the small side rooms (porticus) were extended to enclose the nave. This created more rooms, including chapels and a porch. The twin towers were added in the late 1100s as part of a new west front. At this time, the inner walls of the 8th-century rooms were removed, creating aisles on the north and south sides of the nave.

In the 1200s, the original rounded end (apse) was torn down. The chancel was made more than twice as big, with a triple east window. In the 1400s, north and south porches were added to the nave. At some point, a sundial was added to the south wall of the south tower. Special chapels (chantries) were set up in the church in 1354 and 1371. These were later closed in 1548 or 1549.

The towers had spires by 1414, as shown on an old map. The north tower had a set of bells, reached by a spiral staircase. Adding the towers was a huge investment for a parish church. This suggests that a busy town must have grown up nearby. Even with all the new building, the church kept many important Anglo-Saxon features.

When John Leland visited Reculver in 1540, he was very excited about a tall stone cross inside the church. He said it was "one of the fairest and the most ancient cross that ever I saw." It was about nine feet tall and had carvings of Christ, Peter, Paul, John, and James. Another part showed the Passion of Christ, and a third had the twelve Apostles. The cross was removed from the church by 1784. Archaeologists later studied what they thought was its base. The Reculver cross has been compared to the famous Ruthwell Cross in Scotland. Traces of paint show it was once colorful. Experts now think the cross was carved from a reused Roman column in the 8th or 9th century.

Leland also saw a wall painting of a bishop and a very old gospel book in the church. The gospel book was written in Roman capital letters and had a crystal stone on its cover. This book was likely from the 700s or 800s and might have been imported from Italy.

In its final form, the church was very large. The nave was 67 feet long and 24 feet wide, with aisles on both sides. The chancel was 46 feet long and 23 feet wide. Including the spires, the towers were 106 feet high. The surviving towers alone are 63 feet tall. The towers are connected by a gallery about 25 feet above the nave floor. The entire church was 120 feet long.

Church Decline

When John Leland visited in 1540, he noted that the coastline was eroding. The town was already "but Village lyke." By 1576, Reculver was described as "poor and simple." A map from about 1630 shows the church was only about 500 feet from the shore. In 1658, people complained that the sea had eroded nearly 100 feet of land since the previous September. The village's population was clearly shrinking. By the late 1700s, most residents had left, moving to Hillborough, a mile southwest.

The decline of the village led to the church's decay. In 1776, it was described as "full of solitude, and languished into decay." In 1787, John Pridden noted that the roof had been lowered. He called the church "a weather-beaten building... mouldering away by the fury of the elements." A letter in 1809 said it was "somewhat dilapidated."

Destruction of the Church

In the autumn of 1807, a big storm and high tide caused the cliff to erode right into the churchyard. It destroyed 10 yards of the churchyard wall, very close to the church itself. Sea defenses had been built since 1783, but they hadn't worked well. Two new plans were made to protect the cliff, but they were expensive. Instead, at a meeting on January 12, 1808, it was decided to tear down the church. The vicar, Christopher Naylor, pushed for this. The votes were tied among eight leading residents, so the vicar used his deciding vote for demolition.

Naylor asked the Archbishop of Canterbury for permission. He argued that people would soon lose their burial ground. The archbishop sent others to check, and they agreed in March 1809 that the church should be torn down to save its materials for a new church.

Demolition began in September 1809, using gunpowder. This was a very destructive act.

Most of the church was completely destroyed, except for the western towers. These towers still stand as a landmark for ships. The demolition was very thorough. Today, only the ruins remain on the site. Some materials were used in a new parish church at Hillborough. Fragments of the cross and the two stone columns from the triple arch are now on display at Canterbury Cathedral.

Two thousand tons of stone from the demolished church were sold and used to build the harbor wall at Margate. More than 40 tons of lead from the church roof were sold for £900. In 1810, Trinity House bought what was left of the church from the parish for £100. They wanted to make sure the towers were saved as a navigation aid. They also built the first groynes (structures to protect the coast) to save the cliff. The original spires were destroyed by storms by 1819. Trinity House replaced them with open structures, which were removed after 1928. Today, the church ruins and the Roman fort site are cared for by English Heritage. The sea defenses are maintained by the Environment Agency.

Archaeological Discoveries

The first archaeological report on the demolished St Mary's Church was published in 1878 by George Dowker. He found the foundations of the rounded chancel and the columns of the triple arch. He noted that the original church floor was made of concrete, more than six inches thick. This floor had been described in 1782 as smooth and red. Dowker also found what he believed was the foundation for the stone cross Leland described. The concrete floor seemed to have been laid around it. The chancel floor was raised later and covered with decorated tiles. Dowker also heard about a large, circular burial vault at the east end of the chancel, with coffins arranged in a circle.

More excavations were done in the 1920s by C. R. Peers. He found that the original church nave had doors on the north, south, and west sides. The chancel had doors leading to the side rooms (porticus), which also had outside doors. Peers noted that the concrete floor had a thin layer of pounded brick on top. He believed it was from the same time as the stone foundation for the cross. Excavations also showed steps leading down to the burial vault Dowker mentioned.

Extensions to the side rooms and around the west front were added within 100 years of the church's first build. These extensions had the same type of floor as the original church. Peers suggested that the original church probably had high windows in the nave walls. Areas of walls found by archaeologists but now missing above ground are marked on the site with concrete strips.

The church was a stand-alone building, meaning other monastery buildings must have been separate. In 1966, archaeologists found foundations of what was likely a medieval building near the church. No other such buildings have been found, but they might have been in the area north of the church, which has been lost to the sea. Peers noted that early Canterbury churches also had cloisters on their northern sides. An old building west-northwest of the church, which looked like part of a monastery, was destroyed by storms in 1782. Leland also reported another building outside the churchyard, a former chapel dedicated to St James. This building collapsed into the sea in 1802.

St John's Cathedral, Parramatta

The design of the twin towers, spires, and west front of St John's Cathedral in Parramatta, Australia, is based on St Mary's Church at Reculver. These parts were added to St John's Cathedral between 1817 and 1819. When Governor Lachlan Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth left England for Australia in 1809, efforts to save St Mary's Church were ongoing. Elizabeth Macquarie asked John Watts to design the towers for St John's Cathedral. These towers and its west front are the oldest remaining parts of an Anglican church in Australia. In 1990, a stone from St Mary's Church was given to St John's Cathedral by English Heritage.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |