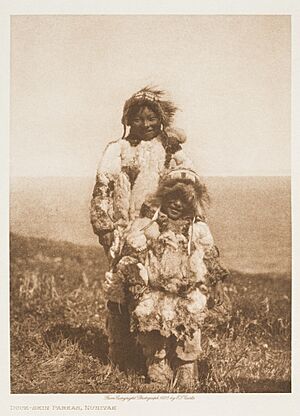

Yup'ik clothing facts for kids

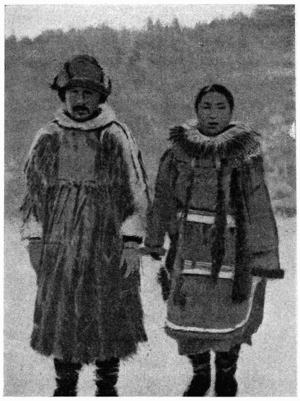

Yup'ik clothing is the traditional style of clothes worn by the Yup'ik people in southwestern Alaska. This includes the Yup'ik, Cup'ik (from Chevak), and Cup'ig (from Nunivak Island) groups. Their clothing system is very effective for staying warm in cold weather, even compared to modern clothes!

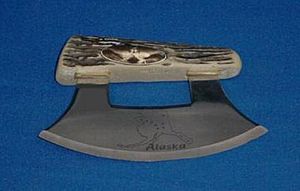

Yup'ik women were skilled at making clothes and shoes. They used animal skins, especially fur from seals, caribou, and other animals. Sometimes they even used bird or fish skins. They sewed these skins together using needles made from animal bones or walrus ivory. The thread they used came from animal tendons, called sinew. The ulu, a special half-moon shaped knife, was used to prepare and cut the skins. Most clothes were made from caribou and sealskin. Yup'ik clothing was usually loose-fitting.

The Yup'ik people respected nature and never wasted anything from their hunts. They used every part of an animal. For example, seal guts were used to make waterproof coats, and fish skins were used for boots. Dried grass was used to make warm socks and even waterproof thread.

Parkas, a type of coat, were more than just clothes for survival. They were also works of art that told stories about the past. Many traditional stories, like those told with a story knife (yaaruin), shared details about Yup'ik clothing, especially the fancy parka called atkupiaq.

When Russian fur traders came to Alaska, they encouraged the Yup'ik people to wear Western-style clothes. This way, more furs could be traded.

Some English words we use today come from Yup'ik words. For example, the word "kuspuk" comes from the Yup'ik word qaspeq, which is a light parka cover. The word "mukluk" comes from maklak, meaning "bearded seal." This is because bearded seal skin was often used for the soles of these soft, knee-high boots. The village of Kotlik gets its Yup'ik name Qerrulliik (meaning "a pair of pants") because the Yukon River splits there, like the legs of trousers.

Kass’artarnek aturanek sap’akinek-llu atulang’ermeng cali Yupiit nutem atutukaitnek aturaqluteng, . . .

"Even though they do wear Euro-American clothing and footwear, they still use original Yup’ik clothing, . . ."—Qipnermiut Tegganrita Egmirtellrit (The Legacy of the Kipnuk Elders) 1998

Contents

Eskimo Clothing

Yup'ik and Iñupiat clothing in Alaska is also known as Eskimo clothing. Eskimo people are usually not tall, but they have strong legs and shoulders. Clothing styles differ between the Iñupiaq people in the northwest and the Yup'ik people in the southwest. Even among different Yup'ik groups, clothing details, speech, and traditions varied. For example, Yup'ik women had four main designs for their fancy parkas, with some local differences.

Native people have lived in the very cold Arctic for thousands of years. They have perfected their caribou skin clothing for 3,000 to 8,000 years. Over time, their clothes have changed and improved, allowing them to live comfortably in harsh weather.

Bodywear

Parkas

The parka (atkuk) is the most common Yup'ik clothing. Parkas were made from many materials like reindeer, squirrel, muskrat, bird, and fish skins, and even intestines. Yup'ik men from the Yukon Kuskokwim area wore long, hooded parkas that reached their knees or lower. Women wore slightly shorter parkas with U-shaped flaps in the front and back.

Parka designs varied by region. For example, women's parkas from the Akulmiut area often had a design on the chest that looked like the tail of an Alaska blackfish. Another Akulmiut design was the "bow and arrow." Parkas from the lower Kuskokwim area had a "pretend drums" design. Men's parkas also had different patterns but were less decorated than women's.

In the Yukon River area, women's parkas were longer than men's, with rounded edges and side slits. Farther south along the Kuskokwim River, parkas for both men and women reached their ankles and usually didn't have hoods. This meant they needed a separate fur hat. Kuskokwim parkas had much more detailed decorations.

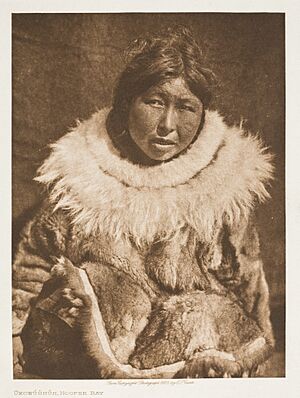

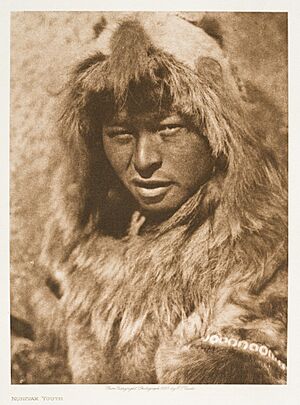

A special feature of Yup'ik parkas was the fancy fur around the hood, cuffs, and bottom edge. This fur is called a parka ruff (negiliq). Yup'iks often used wolverine fur for these ruffs because it doesn't collect frost from breath.

Fancy Parkas

A fancy parka (atkupiaq) is a fur parka made from ground squirrel, muskrat, or mink furs. It has traditional decorations, like a band across the chest with eight tassels. These tassels are said to represent fingers. Yup'ik women still make and wear these parkas for special events. Men's fancy parkas are not made anymore, but elders remember their designs.

The atkupiaq is very popular along the Kuskokwim River. It is very long, with a decorated border of black and white calfskin. Older parkas had fine stitching that looked like footprints in the snow. The hood is smaller than some other Inuit parkas and doesn't have a pouch for carrying a baby.

Every part of a fancy parka, from stitches to fur strips and beads, can tell a story. These parkas are like visual stories, similar to the robes worn by other Alaska Native groups. Traditional Yup'ik stories were often shared through these clothes. Women passed this knowledge to their daughters, so the clothes would show the family's story. Men learned to recognize these stories on the clothing. In the past, wearing fancy parkas was for special events, like festivals in the qasgiq (community house), where animals and spirits were honored. This tradition continues today.

Other types of parkas include:

- Yukon-style parka (ilairutaq): A design borrowed from the northern Inupiaq people.

- Kuskokwim-style parka (qulitaq): Has two pieces of calfskin on the back and two on the chest.

- Tundra (Akula)-style parka (qaliq): Worn by Nelson Island and tundra Yup'iks, with large front and back plates of white calfskin or mink.

- Man's hoodless caribou-skin parka (qaliluk).

- Squirrel-skin parka (uulungiiq): Decorated with a fringe of squirrel bellies.

Nunivak Cup'ig parkas also include styles like kinguqaleg (woman's fur parka cut high on the sides), qatrin (white camouflage parka), qutngug (sealskin parka), and ellangrat (parka made of bleached sealskin and gut or fishskin).

Parka Covers

A parka cover or kuspuk (qaspeq) is a traditional Yup'ik overshirt with a hood. Both men and women wear kuspuks. Men usually wear them for special events like Eskimo dancing (yuraq), while women wear them as everyday clothes. Kuspuks have long sleeves, a hood, and a large front pocket. They often have decorative trim. Women's kuspuks usually have floral patterns, while men's are solid colors. Women's kuspuks can also have a skirt, making them look like a dress. The skirted version is called the "Kuskokwim style kuspuk," and the skirtless type is the "Yukon style kuspuk."

Gut Parkas

A gut parka (imarnin) is a hooded, waterproof raincoat made from the intestines of seals. These parkas were perfect for wet weather and traveling in kayaks. They are still effective today. Gut parkas can also be made from bear intestines. They are decorated with fur from wolverine, bear, wolf, and other animals, or with bird feathers. The Russians called these parkas kamleika, a word now used for any gut parka.

Fish Skin Parkas

A fish skin parka (qasperrluk) is a type of clothing made from fish skin. In the past, both men and women wore these for hunting and traveling. In winter, they were worn over fur parkas. A Yukon fish skin parka might be made from dog salmon skin. Nunivak men wore parkas made of silver salmon skin, while women's were made of salmon trout skin and often had a white fox ruff. The Nunivak Cup'ig people bought prepared fish skins from Yup'ik people on the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers.

Bird Skin Parkas

A bird skin parka (tamacenaq) is made from the skins of birds like ducks, loons, and gulls. Bird skins make very warm parkas. Thick bird skin parkas were ideal for winter and cold summer days. Yup'ik and Inuit seamstresses had different ways of preparing bird skins and making these parkas. Today, bird skin parkas are rarely made, and the skills are disappearing. In the 19th century, many Yup'iks along the coast wore bird skins because birds were plentiful. A baby wrapped in eider skin would be warm and dry.

Nunivak Cup'ig bird skin parkas include alpacurrlugar (murre skin parka), cigurat atkut (guillemot skin parka), qilangar (puffin skin parka), and aarraangiarat (oldsquaw skin parka). Seabirds like murres and puffins were common for clothing. Cormorant and eider skins were considered more valuable. Bird skin parkas are light and comfortable but tear easily. They were often reversible, worn with feathers inside for warmth in winter, and feathers outside for sleeping. They usually didn't have fur strips or beads because of their bulk.

Pants

Pants (qerrulliik) were traditionally made from sealskin or fur. Both men and women wore fur trousers. Today, many Yup'ik people wear pants made of cloth. Knee-length pants were worn under parkas. The village of Kotlik gets its Yup'ik name Qerrulliik (meaning "a pair of pants") because the Yukon River splits there, like the legs of trousers.

Trouser-boots (allirtet) were pants with attached socks made of fur. Women wore these, made from a single small harbor seal skin. Very short trousers made from sealskin were also worn. Men's sealskin pants needed two skins and were not hemmed at the bottom.

Headwear

The hood or parka hood (nacaq) is a common part of the parka. Inuit and Yup'ik people usually wear parkas with attached hoods and fur ruffs to protect their faces. These hoods are often trimmed with Arctic fox, wolf, or wolverine fur. The Eskimo Nebula in space is even named because it looks like a person's head surrounded by a parka hood!

A separate hood (yuraryaraq) was used with hoodless parkas, especially for travel. These were made of squirrel skin or dyed fish skin strips.

The hood ruff (negiliq) is the fur trim around the face on a parka hood. It's not like a Western neck collar. Both men's and women's hoods had a large "sunshine ruff" made from wolverine and fox fur. This ruff was designed to look like sun rays around the face. Fancy parkas had three or four layers of different colored furs on their ruffs.

A fancy hat (nacarpiaq) is a Yup'ik men's ceremonial headdress with fur strips hanging over the shoulders. These hats were worn for opening ceremonies and dances. They were made from bird feet leather, beads, pearls, and furs like mink, otter, wolf, and wolverine. The Yup'ik believe animals sacrifice themselves for the wearer's survival. Nunivak Cup'ig men wore caps with many fur strips. They also wore wolf head caps for ceremonies, made from an entire wolf head skin.

A circular cap (uivqurraq) is a cap made of squirrel or other skin, often with beaded designs that look like wood knots. People in regions south of the Yukon River wore these caps when their parkas didn't have hoods.

A dance headdress (nasqurrun) is a crown-like hat decorated with beads and fur from wolf, wolverine, or ermine. It might also have bear claws or caribou hair. These are used for Eskimo dancing. In coastal villages, men who led ceremonial songs wore caribou-hair headdresses. Women wore similar headdresses, which are still part of modern Yup'ik dance outfits for both sexes.

A steambath cap (maqissuun) is headwear worn in a steambath (maqivik). Men protected their heads with crude caps made of puffin, eider duck, or murre skins.

A full-conical hunting hat (ugtarcuun) is shaped like a pointed piece of ice. These bentwood hats helped seal hunters hide in their white kayaks among floating ice. They also shaded a man's eyes from sun glare. These hats were worn during spring seal hunting and the Bladder Festival, a ceremony to honor seals.

A semi-conical hunting visor (elqiaq) is an open bentwood hat decorated with feathers. It protected eyes from sun glare. Craftsmen softened wood with hot water, bent it, and stitched the ends together. Animal carvings were added as good luck charms for hunting. Feathers might have helped hunters feel like birds, as in old stories.

Snow goggles (niguak) are old-style goggles made of wood with narrow slits. These slits let in only a little light. They were carved from driftwood, walrus ivory, bone, or caribou antler. Sometimes they were made with coarse seashore grass. The inside was always painted black to reduce glare. Goggles were carved in different styles and often looked like animals, showing the belief in human-animal transformation. The narrow slits protected eyes from bright light and also helped focus vision, like a pinhole camera. Snow goggles are an ancient part of Eskimo hunting cultures, found in archaeological sites up to 2,000 years old.

Handwear

Gloves (aasgaaq) were usually made from caribou or sealskin. Sometimes they were made from fish skin or dried grass. Fancy ceremonial gloves were called aiggaqtaaq.

Mittens (aliiman) were also common. Long, waterproof mittens (arilluk) were made from dehaired sealskin or fish skin. Fish skin mittens with grass liners were used for kayak travel in bad weather. To prepare fish skins, they were soaked in urine, scraped clean, and then freeze-dried.

People wore waterproof salmon-skin mittens to keep their hands dry while kayaking, driving a dog sled, or working with fishing nets. Woven grass liners were put inside for warmth. Wrist-length mittens were often made from leftover seal or caribou skin. Women wore fur mittens that reached almost to their elbows.

Footwear

Yup'ik footwear, especially Eskimo skin boots known as mukluks, are designed for efficiency, comfort, and durability in different weather, seasons, and terrains.

The sole (alu) is the bottom of a boot that touches the ground. Yup'ik soles are traditionally made from bearded seal skin, which is chewed to make it soft and moldable. A special oversole (nat'raq) was used to prevent slipping on ice. Boot soles were sometimes cut from old kayak covers made of bearded seal skins. Yup'ik boot soles are very thick, sometimes up to five centimeters.

Winter boots had soles of dehaired bearded seal and legs made from haired ringed or spotted seal. Red yarn was often used for decoration around the toe and heel seams. Dance boots sometimes used lighter materials like ringed seal skin. Moose-leg skins and commercially tanned calfskin are also used today.

Mukluks are soft, knee-high boots traditionally made of seal or caribou skin. Alaskan Athabaskan mukluks are made of moose hide with fur and beadwork. There were many types of Yup'ik mukluks, including kamguk, kameksak, and piluguk. The word "mukluk" comes from maklak, meaning "bearded seal," because bearded seal skin was used for the soles. The lower part of caribou front legs was used to make kameksaq and piluguq boots.

- Calf-high mukluk (piluguq): A winter skin boot worn by both men and women. Men's boots were larger and usually not decorated, while women's boots were.

- Knee-high mukluk (kamguq): A knee-high or taller skin boot.

- Ankle-high mukluk (kameksaq): An ankle-high skin or fur boot, or a house slipper.

- Fancy mukluk (ciuqalek): A fancy skin boot with a piece of dark fur on the shin and back.

- Waterproof mukluks (ivruciq): Waterproof sealskin boots worn by men. Women's thigh-high waterproof boots were called at'arrlugaq.

- Fish-skin boots (amirak): Waterproof boots made of fish skin. Large salmon skins were prepared by sewing up fin holes. A round needle was used to avoid splitting the skin.

Other Yup'ik and Cup'ik skin boots include atallgaq (ankle-high), ayagcuun (thigh-high), catquk (dyed sealskin), and qaliruaq (ankle-high for dress wear or slippers).

Socks (ilupeqsaq) were used as liners for boots. Loon skin socks were made from bird skin. Grass socks made from coarse seashore grass were worn inside sealskin boots. The boots were also lined with grass at the bottom. Grass boot liners (alliqsiik) kept feet insulated and dry.

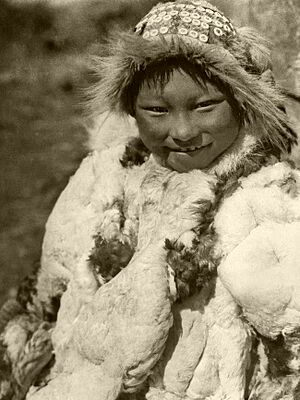

Children's Clothing

Children's clothing (mikelnguut aturait) was made from the soft skin of younger animals. Baby parkas were made from reindeer fawn and puppy skins, with the fur on the inside. Puppies one or two months old were sometimes used for this purpose. For a sealskin parka, one skin was needed for a three-year-old, two for a five or six-year-old, and three for a child of 10 or 12. A small child's sealskin parka was often decorated with tassels. Baby boots always had the fur inside and were similar to adult boots. In the past, babies wore long boots and no pants. Once a child was toilet trained, boys wore separate pants, and girls wore trouser-boots like women.

Children often received gifts of traditional clothing from their namesake's relatives, including a complete set of "head to toe" clothing.

Trimming

Trim (naqyutkaun) refers to decorative pieces on parkas, hats, and boots, such as patchwork or tassels. Parka trim was often made of white and black caribou or reindeer skin, now often replaced by calfskin. Wolf and wolverine fur are used for parka trimming. Wolverine fur is especially good for hood ruffs because it doesn't collect frost from breath and blocks wind.

Yup'ik non-hanging trims include:

- akurun: Trim at the hem of a parka, often with geometric designs.

- tungunqucuk: Wide strip of otter fur below light-colored decoration.

- cenliarun: Trimming on the hem of a garment.

- alirun: Trim around a parka cuff.

- tusrun: Short, narrow, V-shaped calfskin on a parka sleeve.

- pukiq: Light-colored, soft belly skin of caribou used as trim.

- naqyun: Trim on a parka or kuspuk.

The black skin of wolf fish was used for trim on parkas in the Yukon and Norton Sound areas.

Tassels (alngaq) are hanging decorative ornaments of wolverine fur or beads on a parka or boot. Some Yup'ik tassels include:

- kayurun: Wolverine-fur decoration on the upper parka sleeve.

- megcugtaq: Wolf fur piece on the shoulder or armpit tassels, representing falling snowflakes.

- pitgarcuun: Tassel from the armpit with red beads, said to represent the blood of the legendary hero Apanuugpak.

- qemirrlugun: Calfskin piece in the middle of a parka with three tassels, often with a "drawn bow and arrow" or fish-tail design.

- miryaruaq: One of two tassels on the chest and back of parkas, said to represent caribou fat.

Apanuugpak was a legendary Yup'ik warrior from the 18th century. His stories are considered historical. He believed war was wasteful. Yup'ik parkas told his legend. For example, two white strips on the shoulder meant "don't tread on me, I'm a member of Apanuugpak's tribe." Actor Robert Redford tried to make a movie about him called "The Winter Warrior," but it was never finished.

Armbands (kayurun) were worn by men during dances without a parka. They were made of seal or caribou skin with fur inside and decorated with dog fur or other fancy furs.

Tools

Yup'ik women were skilled at sewing skins. While everyday items like mittens and mukluks are still made, the elegant fancy parkas are now rare. Proper skin sewing requires a lot of traditional knowledge and help from family members for hunting, gathering, and preparing materials. Women's tools include the ulu, scraper, needle, needle case, thimble, and patterns. These tools varied by region.

Ulu

The ulu (uluaq), also called an Eskimo knife or woman's knife, is a multi-functional, half-moon shaped knife. Ulus come in different sizes for different tasks, like skinning animals, preparing meals, cutting skins for boats, and sewing clothes.

Scraper

A scraper (tellunrun) or skin scraper is used to prepare skins. After skins are dried, they must be scraped to make them soft enough to sew. A sharp scraper removes any dried fat. A large piece of bent wood (tuluruaq) was used as a scraping board.

Sinew

Sinew (yualukaq) is a strong thread made from the tendons and ligaments of animals. Tendons from large animals like caribou, moose, and beluga whales were used for sinew. Dried animal tendons were used to make clothing, footwear, bedding, tents, and kayak covers. Yup'iks used caribou, moose, or beluga sinews as thread. Hand-twisted sinew thread was called yualukiuraq.

Needle

A needle (mingqun) is the main tool for sewing. In the past, Alaska Eskimos carved fine sewing needles from walrus ivory or bird bones. Small holes were drilled with a mouth-bow drill. Today, metal needles are used. A three-cornered needle (quagulek) was used to sew lightweight skin without pre-punching holes. A crane's foot needle (kakuun) was made from the front part of an uncooked crane's foot.

Needle Case

A needle case (mingqusvik) held needles. Yup'ik people preferred bone or ivory needle cases with stoppers at each end. Needles were also stored in the hollow part of a swan wing bone.

Thimble

A thimble (akngirnailitaq) is worn on a seamstress's index finger to protect it from needles. Thimbles were made of metal, ivory, or skin from bearded seals. Shell thimbles were also used.

Sewing Bag

A sewing bag (kakivik) or sewing box held a woman's needles, thimble, sinew thread, small knife, and whetstone. A woman's ability to sew and repair clothes was very important for her family's survival. Girls had to learn to sew before they could become wives. Men also sewed repairs for themselves while hunting.

Patterns

Patterns (cuqcaun) are used to cut and sew clothing. Yup'ik pattern-makers used rectangles, squares, rhombuses, and right triangles to create beautiful, symmetrical designs, similar to patchwork. They used two contrasting colors to make visually pleasing effects. These patterns were used for parka borders, headbands, and boots.

Yup'ik mathematics and science helped them solve problems of living in the tundra. The human body was central to their math. Clothing patterns also helped teach geometry and literacy. Traditional geometric patterns on parkas told stories about legendary people, identified regions, and showed family connections. For example, the "knuckle" measurement (the middle part of the index finger) was a common unit for making squares, which were then used for patterns on squirrel parkas or ceremonial headdresses.

Materials of Yup'ik Garments

Raw Materials

Yup'ik people mostly fished, but hunting also provided food and skins for clothes. Their fur and skin clothing was key to their survival in the far north. The main materials for traditional Yup'ik clothing are skin, fur, intestines, sinew, and grass. These materials come from sea and land mammals, birds, fish, and plants. Hunting clothes were designed to be warm and waterproof. Fish skin and marine mammal intestines were used for waterproof outer layers and boots. Grass was used for warm socks and waterproof thread. Yup'ik elders used every bit of their hunts: seal guts became warm, waterproof parkas; fish skins became mittens; and dried grasses became socks, bedding, or even goggles.

Skin and Fur

Skin (amiq) and fur (melquq) were essential. Clothing could be made from bearded seal, hair seal, walrus, caribou, bear, wolf, wolverine, duck, swan, and fish skins. Nunivak Cup'ig clothing was mostly made from seals, caribou, or birds. Mink and fox skins were also used. Muskrat and Arctic ground squirrel skins were used for winter parkas because they are light and warm. Caribou skin is also very warm and durable, making it a top choice for winter clothing.

Traditionally, Nunivak Cup'ig skin clothing was washed in urine, but this practice became rare by 1939.

Fur from land animals was warmer than other skins. Red and white fox skin parkas were warm. Mink, otter, and muskrat skins were also used. Trapping fur-bearing animals provides income for many Alaska Natives. Animals trapped for fur include bears, beaver, fox, hare, lynx, mink, muskrat, otter, squirrel, weasel, wolf, and wolverine. Wolverine hair is ideal for parka hood ruffs because it doesn't collect frost and blocks wind.

Gut

Gut (qilu) or intestines, especially from walrus or bearded seals, were used to make waterproof rain parkas and boots. Bear gut parkas were said to last longer than seal gut parkas. The smooth inside of the gut became the outside of the parka.

Tendon

Tendon (yualuq), also called sinew or thread, is made of strong bundles of collagen fibers. Caribou, moose, and beluga whale tendons were used to make sinew for sewing.

Resources

The Yup'ik homeland is a subarctic tundra environment. Their lands are in different parts of Alaska:

- Nulato Hills: Low hills between the Bering Sea and the Yukon River.

- Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: A large delta formed by the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers, the heart of Yup'ik territory.

- Ahklun Mountains: Mountains in the southwest that divide river drainages.

- Bristol Bay Lowlands: Flat lowlands around Bristol Bay.

- Bering Sea Islands: Major islands like Nunivak and St. Lawrence.

Sea Mammals

Marine mammals (imarpigmiutaq), like seals and walruses, were important resources. Four species of ice seals (ringed, bearded, spotted, and ribbon seals) were used for food, oil, and materials for clothing and crafts. Sealskin is wind and water-resistant. Sealskin parkas were common in the past, requiring about five skins for one parka. Seal hide and sinew were used for clothing, rope, and nets. Intestines were used for waterproof parkas.

- Bearded seal (maklak): The best-known seal, preferred for meat. Its hide was used for boot soles, rope, and mats.

- Ringed seal (nayiq): Known as "winter seal," preferred for oil. Skins were used for clothing like boots, pants, mittens, and hats.

- Spotted seal (issuriq): Skins were used for slippers, boots, mittens, and parkas.

- Ribbon seal (qasruliq): Hunted less often, but skins were used for decoration or ceremonial clothing because they tear easily.

- Walrus (asveq): Hunted for food and ivory. Walrus ivory was traded. Walrus intestines were also used for rain parkas.

- Beluga whale (cetuaq): Dark beluga whale sinew was sometimes used for decorative stitching.

Land Mammals

Terrestrial mammals (nunarmiutaq) include game animals and furbearers.

- Caribou (tuntu): Caribou skin is ideal for cold, dry weather because its hair traps air, providing excellent insulation. Caribou skins were used for clothing, sleeping bags, and fancy parkas. Historically, caribou were hunted for meat and skins.

- Reindeer (qusngiq): Domesticated caribou, introduced to Alaska. Reindeer hides are used for clothing, mukluks, blankets, and tents. Their sinew is used for thread.

- Moose (tuntuvak): Moose hide is used for mukluks.

- Muskox (umingmar): Muskox were reintroduced to Nunivak Island. Their soft underwool, called qiviut, is used to make fine clothing.

- Furbearers (melqulek): Animals like beaver, otter, fox, mink, and squirrel are trapped for their pelts. Their furs are used for parkas and trimming.

- Bears (brown, black, polar): Bear skins were used for mukluks and trim.

- Wolf (kegluneq): Wolf fur is used for parka trimming.

- Dog (qimugta): Puppy skins were used for baby parkas.

- Foxes (red, Arctic): Fox skins were used for warm parkas and ruffs.

- Wolverine (terikaniaq): Wolverine hair is ideal for parka hood ruffs because it doesn't collect frost. Wolverine cuffs help warm wrists.

- Muskrat (kanaqlak): Muskrat skins were used for parkas.

- Squirrel (qanganaq): Ground squirrel pelts were preferred for fancy parkas because they are warm and light.

Birds

Birds (tengmiaq) were used for parkas, caps, and tools. Their feathers and bones were used for many things, like fire-bath hats, dance fans, and needles.

- Eider ducks (common, king, Steller's): Eider skins were used for warm parkas, especially for children.

- Long-tailed duck (allgiar(aq)): Skins were used for women's parkas.

- Swan (qugyuk): Swan skins were used to make parkas.

- Sandhill crane (qucillgaq): Needles were made from the front part of a crane's foot.

- Murre, guillemot, auklet, puffin, kittiwake, cormorant, owl: Skins from these seabirds were commonly used for parkas and caps.

Fish

Fish (neqa) skins and intestines were used for waterproof clothing in some areas. Fish skin was used for waterproof boots and mittens, and even parkas for summer. The sinew for fish skins was called yualunguaq.

- Pacific salmons (dog, silver, king): Skins from various salmon species were used for clothing.

- Trout (charr): Skins were also used for clothing.

Plants

Plants (naunraq) were also important resources.

- Trees: Along the treeless coast, driftwood was the main source of wood. Spruce wood was used for shoehorns, skates, snowshoes, and boot insoles.

- Alder (cuukvaguaq): Alder bark was used to dye boots and clothing red.

- Grasses (canek): Used as insoles for fish skin boots, kuspuks, and mittens. Dried grass was used for insoles (piinerkaq) and woven grass socks.

- Coarse seashore grass (taperrnaq): Used to make mittens, socks, mats, and baskets. Men wore grass socks and folded grass insoles inside their water boots.

Western-style Clothing

The Russian Empire colonized parts of North America from 1732 to 1867. Russian fur traders encouraged Eskimos to sell their furs and use manufactured materials instead. This meant Eskimos adopted Western-style clothes so more furs could be traded.

Many Russian words were borrowed into the Yup'ik language during this time. For example, sap’akiq (shoe) comes from the Russian word for shoes, sapogí. Kamliikaq (waterproof jacket) comes from the Russian kamléyka.

Today, many Yup'ik people wear Western-style clothing.