Aberdare strike 1857–1858 facts for kids

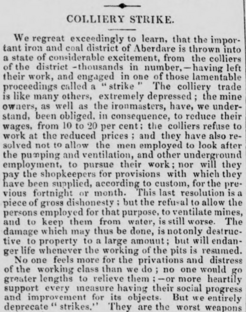

The Aberdare strike was an important event for coal miners in South Wales. It happened between 1857 and 1858. This strike was one of the first big disagreements between workers and bosses in the steam coal industry.

The strike started because coal mine owners wanted to cut miners' wages. They planned to reduce pay by up to 20%. This was due to a tough economic time after the Crimean War. During the strike, miners in the Aberdare Valley formed a trade union. This union helped them work together. However, the miners eventually had to go back to work. They had to accept the lower pay set by the mine owners.

Contents

Why the Strike Started

In late 1857, rumors spread that coal owners would cut wages. Miners knew some pay cut might happen. A meeting of miner representatives agreed to talk to the owners. They wanted to ask for a smaller pay cut.

Some important local people supported this peaceful approach. One was Thomas Price, a well-known minister. He was also the editor of a Welsh newspaper called Y Gwron. But the owners refused to talk. So, the miners ignored Price's advice and went on strike.

What Happened During the Strike

At the start of the strike, there were a few reports of trouble. Some engineers were keeping the mines running. They were sometimes threatened. The engineers managed to keep most mines working. But at Shepherds Pit in Cwmaman, the engineers joined the strike.

Because of the tension, soldiers were sent to Aberdare. They first stayed at the Town Hall. Later, they moved to Cardiff. This happened when fears of disorder calmed down. Henry Austen Bruce, a local Member of Parliament, helped with this. Overall, the strike was mostly peaceful. A new trade union movement grew stronger during this time. The Merthyr Telegraph newspaper criticized other papers. It said they made the disorder in Aberdare sound much worse than it was.

Coal owners in the area saw themselves as Welsh business leaders. They usually had good relationships with their workers. Men like David Williams (Alaw Goch) found themselves against their employees. Williams wrote a letter to the Merthyr Telegraph. He disagreed with the miners' claims. The miners said the price of steam coal had not gone down. Williams did not blame the men for wanting to keep their wages. But he did mention threats, like flooding the mines.

Public Meetings in Aberdare, December 1857

Henry Austin Bruce, the MP for Merthyr Boroughs, spoke for the mine owners. He held meetings in Mountain Ash and Aberdare. He explained the owners' side to large groups of workers.

At a public meeting in Aberdare's Market Hall, he asked the miners to return to work. Bruce said his family had many interests in the coal industry. But he also claimed he wanted to help end the strike peacefully. In his long speech, Bruce argued that owners were fair to cut wages. He said this was because of the general economy. He also mentioned the state of the coal and iron businesses.

Many people attended this meeting. A newspaper reported that no one interrupted Bruce's speech. Rev David Price of Siloa, Aberdare translated Bruce's speech. This was for those who did not speak Welsh. This meeting was important because several strike leaders spoke. These included David Williams, John Jones (Gwalch), and John Davies.

Bruce's first speech was quite calm. But then he criticized the miners' demands. He compared their pay requests to what farm workers earned. He talked about extreme ideas from trade unions elsewhere. He also mentioned threats and violence in the area. Thomas Price of Calfaria, Aberdare translated these comments. His fellow minister, David Price, then shared his own experience as a striking miner years ago.

This understanding between Bruce and these ministers showed something important. Chapel leaders often did not support trade unions. One report said Thomas Price added his own comments. He tried to get the men to go back to work. His actions at this meeting were remembered later. They came up during the 1868 General Election, when Bruce lost.

It was thought that about 6,500 miners were on strike by this meeting. Newspapers reported the strike was peaceful. They also noted the strange quietness in the busy Aberdare Valley. Furnaces that had burned for twenty years were put out. At night, the main light came from the ironworks in Merthyr.

On December 14, two days after the Aberdare meeting, a huge meeting of miners took place. About 10,000 miners gathered on Hirwaun Common. Unlike the Market Hall meeting, only miner leaders spoke here. One leader, Lewis Morgan, said miners were being tricked about coal prices. He claimed the wage cuts were much bigger than needed. Other reports showed some sympathy for the miners. They said wages had not gone up when coal prices increased. Miners also complained about new machines. These machines changed traditional coal cutting methods. The Baptist newspaper, Seren Cymru, stressed how peaceful this Hirwaun meeting was.

How the Strike Ended

By mid-December, some people who had supported the miners changed their minds.

On January 12, a meeting was held in Mountain Ash. Strikers from Monmouthshire valleys were expected. But false rumors had reached Monmouthshire. They said the strike was over in Aberdare. Because the Monmouthshire delegates did not show up, divisions appeared among the miners. An old miner urged everyone to return to work. But most disagreed.

Some threatening notices were posted in the valley around this time. They were like those from earlier disputes in South Wales. A famous example was a letter supposedly from Y Tarw (The Bull). It said: To my faithful Brethren in the strike. I am very thankful to all of you for your valuable services in assisting me in my present troubles. Be faithful for a little while yet, and we will win the day. The letter then made vague threats of violence. At a meeting in Aberdare's Market Place, John Jones (Gwalch) clearly said he did not write this letter.

Another meeting happened at Hirwaun Common. It was reported that some coal owners had brought in new workers. These workers were meant to replace those on strike. Coal trimmers from Cardiff were said to be working at Mountain Ash. Thirty miners from Pembrokeshire were reported at Cwmpennar. But they seemed to refuse to work after learning about the strike.

Eventually, the miners had to go back to work. They accepted the terms set by the owners. This event later became important in the history of the valley. It also affected the local parliamentary elections.

Some people believe a religious revival in 1859 was partly started by coal owners. They wanted to regain control over their workers.

Sources

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |