Asiento de Negros facts for kids

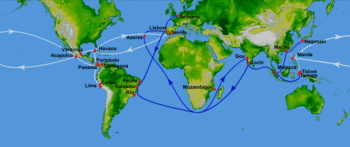

The Asiento de Negros (which means "agreement of blacks" in Spanish) was a special contract. It gave certain merchants the exclusive right to bring enslaved Africans to the Spanish colonies in the Americas. The Spanish Empire usually didn't trade enslaved people directly from Africa. Instead, they hired foreign merchants, often from Portugal, Genoa, the Netherlands, France, and Britain, who were more involved in this trade. The Asiento focused only on Spanish America, not the French or British Caribbean islands.

A treaty from 1479, called the Treaty of Alcáçovas, divided the Atlantic Ocean into Spanish and Portuguese zones. Spain got the western side, which included South America and the West Indies. Portugal got the eastern side, including the west coast of Africa. Spain needed enslaved African labor for its colonies in America. However, Spain didn't have any trading posts or land in West Africa, where most enslaved people were taken from. So, Spain had to rely on Portuguese traders to supply them. These contracts were usually given to foreign banks. These banks worked with local or foreign traders who specialized in shipping. Different groups and people would compete to get the Asiento contract.

The main reason for bringing enslaved Africans was to reduce the harsh labor demands on the native people of the colonies. The enslavement of Native Americans had been stopped partly due to people like Bartolomé de las Casas. Spain first gave individual Asientos to Portuguese merchants to bring enslaved people to South America.

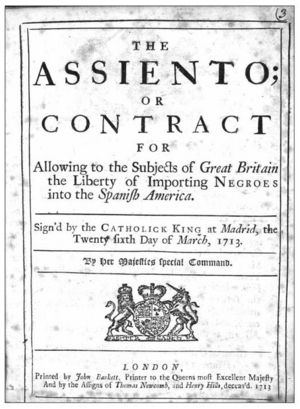

After the Treaty of Münster in 1648, Dutch merchants also became involved in the Asiento de Negros. In 1713, Britain gained the right to the Asiento as part of the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession. The British government then gave its rights to the South Sea Company. The British Asiento ended with the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, signed between Great Britain and Spain.

Contents

What Was an Asiento?

An asiento in Spanish means a short-term loan or debt agreement. It usually lasted one to four years. The Spanish crown would sign these agreements with bankers or groups of bankers (called asentistas). These loans were often made against future money the crown expected to receive, especially after peace treaties.

An Asiento could cover one or more types of deals: a short-term loan without security, a payment transfer, or a currency exchange. From the early 1500s to the mid-1700s, Spanish treasurers used Asientos to manage their money when income and spending didn't match. The king promised to pay back the loan amount plus high interest (12%). The bankers involved, from cities like Seville, Lisbon, Genoa, and Amsterdam, made money from this. They also got direct investments from many Atlantic merchants. In return for scheduled payments, merchants and bankers could collect certain taxes or oversee trade in goods that the king controlled. This way, some merchants got the right to ship tobacco, salt, sugar, and cacao from the Spanish West Indies. Sometimes, they also got licenses to export precious metals from Spanish America or Cadiz. The Asiento greatly affected the economy of Spanish American colonies. It guaranteed a steady income for the crown and a supply of goods for the region. The contracting party took on the risks of the trade. A new Asiento was often the safest way for them to get their money back.

History of the Asiento Contract

Why the Asiento System Started

The word asiento comes from the Spanish verb sentar, meaning "to sit." In a business sense, it means "contract" or "trading agreement." It was a term in Spanish law for any contract made for public benefit between the Spanish government and private individuals.

The Asiento system began after Spain settled in the Caribbean. The native population there was dying out quickly, and the Spanish needed another source of labor. At first, some Christian Africans born in Spain were brought to the Caribbean. But as the native population continued to decline, and people like Bartolomé de Las Casas spoke out against exploiting native labor, the young King Charles I of Spain allowed enslaved people to be brought directly from Africa to the Caribbean.

The first Asiento for selling enslaved people was made in August 1518. It gave a Flemish friend of Charles, Laurent de Gouvenot, a monopoly to import up to 4,000 enslaved Africans over eight years. Gouvenot quickly sold his license to others, including Genoese merchants. The Casa de Contratación in Seville controlled trade and immigration to the New World. Enslaved Africans were seen as goods, and their import was controlled by the crown. The Spanish crown collected a tax on each "pieza" (a measure of an enslaved person's value), not on each individual. Spain did not have direct access to African sources of enslaved people or the ships to transport them. So, the Asiento system was a way to ensure a legal supply of Africans to the New World, which also brought money to the Spanish crown.

Portuguese Control of the Asiento

For the Spanish crown, the Asiento was a way to make money. It was a key policy for the Spanish government to control and profit from the slave trade. In Habsburg Spain, Asientos were a main way to fund government spending.

At first, Portugal controlled the European trade of enslaved Africans. This was because of the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which gave Portugal rights in West Africa. Before the official Asiento began in 1595, when the Spanish king also ruled Portugal, Spain gave individual Asientos to merchants, mostly from Portugal. These merchants brought enslaved people to the Americas. In the 1560s, most of these enslaved people came from the Upper Guinea area, especially Sierra Leone, where there were many wars.

After Portugal established the colony of Angola in 1575, and Brazil became the main sugar producer, Angolan interests took over the trade. Portuguese bankers and merchants got the larger, more complete Asiento that started in 1595. This was during the time when Spain and Portugal were united. The Asiento also covered the import of enslaved Africans to Brazil. Those who held Asientos for Brazil often traded enslaved people in Spanish America too. Spanish America was a big market for enslaved Africans, including many who were sold illegally beyond the Asiento's limits. From 1595 to 1622, about half of all imported enslaved people went to Mexico. Most smuggled enslaved people were not brought by independent traders.

Angola became very important in the trade after 1615. The governors of Angola, starting with Bento Banha Cardoso, worked with Imbangala soldiers to cause chaos among local African powers. Many of these governors also held the Angola contract and the Asiento, which protected their business interests. Shipping records from Vera Cruz and Cartagena show that up to 85% of the enslaved people arriving in Spanish ports were from Angola, brought by Portuguese ships. In 1637, the Dutch West India Company hired Portuguese merchants for the trade. The early Asiento period ended in 1640 when Portugal rebelled against Spain. Even then, the Portuguese continued to supply Spanish colonies.

Competition from Dutch, French, and British Traders

In the 1650s, after Portugal became independent from Spain, Spain refused to give the Asiento to the Portuguese, seeing them as rebels. Spain tried to enter the slave trade directly, sending ships to Angola. It also thought about forming a military alliance with the powerful African kingdom of Kongo. But these ideas were dropped. Spain went back to relying on Portuguese and then Dutch traders to supply enslaved people. The Spanish gave large Asiento contracts to the Genoese banker Grillo in the 1660s and the Dutch West India Company in 1675.

In 1700, the last Habsburg king of Spain, Charles II, died without children. His will named Philip V of Spain from the House of Bourbon as his successor. The Bourbon family also ruled France. So, in 1702, the Asiento was given to the French Guinea Company. This company was to import 48,000 enslaved Africans over ten years. These Africans were transported to the French Caribbean colonies of Martinique and Saint Domingue.

To keep a balance of power in Europe, Great Britain and its allies, including the Dutch and Portuguese, challenged the Bourbon claim to the Spanish throne. They fought the War of the Spanish Succession against French and Spanish power. Although Britain did not win everything, it did receive the Asiento as part of the Peace of Utrecht. This gave Britain a thirty-year Asiento to send one merchant ship to the Spanish port of Portobelo, supplying 4,800 enslaved people to the Spanish colonies each year. The Asiento became a way for British smugglers to bring in illegal goods. This weakened Spain's efforts to control trade with its American colonies. Disputes related to the Asiento led to the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739). Britain gave up its rights to the Asiento after the war, in the Treaty of Madrid of 1750. Spain was making several administrative and economic changes at the time. The Spanish Crown bought out the South Sea Company's right to the Asiento that year. The Spanish Crown then tried to find other ways to supply enslaved Africans. They tried to allow more free trade in enslaved people by Spaniards and foreigners in specific colonial locations. These included Cuba, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, and Caracas, all of which used many enslaved Africans.

Who Held the Asiento Contract?

Early Asiento Holders: 1518–1595

- 1518–1527: Laurent de Gouvenot, a governor and official for Charles I of Spain. The first known transatlantic slave ship sailed in 1525.

- He outsourced the work to Domingo de Forne, Agustín de Ribaldo, and Fernando Vázquez, who were Genoese merchants in Seville.

- 1528–1536: The Welser and Fugger families from Augsburg (Germany).

- 1536–1595: During this period, the trade was more open, with many individual contracts.

Portuguese Asiento Holders: 1595–1640

Six Asientos were given during this time:

- 1595–1601: Pedro Gomes Reynel.

- 1601–1604: João Rodrigues Coutinho.

- 1604–1615: Gonçalo Vaz Coutinho.

- 1615–1623: António Fernandes de Elvas. The main places where enslaved people were brought in Spanish America were Cartagena de Indias (in modern Colombia) and Veracruz (in modern Mexico). From there, they were sent to places like Venezuela, the Antilles, and Lima.

- 1623–1631: Manuel Rodrigues Lamego. 59 ships were licensed for Africa, where about 8,000 enslaved Africans were bought from West African merchants, mostly from Luanda.

- 1631–1640: Melchor Gómez Angel and Cristóvão Mendes de Sousa.

In 1640, the union between Spain and Portugal ended, and the Portuguese Restoration War began. There was no Asiento between 1640 and 1651, and the arrival of enslaved people in Spanish America dropped sharply. In 1641, Portugal and the Dutch Republic signed a treaty allowing Dutch ships in Portuguese ports for ten years. Dutch merchant Jan Valckenburgh saw an opportunity. Dutch private businesses were responsible for almost half of the total investment in the slave trade.

The invasion of Jamaica by the English led to the Anglo-Spanish War (1654-1660). In 1659, the Danish Africa Company was started to compete with the Dutch, Swedish, and Portuguese. The Dutch competed with the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa, founded in 1660. Both of these trading powers had a strong presence on the Gold Coast and the Bight of Benin. Many enslaved people came from areas like Cross River, Calabar, and West Central Africa. The Dutch and Portuguese signed a new treaty in 1661. Matthias Beck, a Dutch official, was appointed governor of Curaçao. From 1662 to 1728, Curaçao served as a hub where enslaved people on Dutch ships reached Spanish colonies. Another route for the slave trade within America started in Barbados and Jamaica.

Genoese Asiento Holders: 1662–1671

In 1658, Ambrogio Lomellini and Domingo Grillo were appointed "Treasurers of the Holy Crusade." This gave them access to some treasures from America. In the 1660s, Spain's royal finances were in trouble. The Dutch West India Company had slave contracts with Grillo and Lomellini, who were allowed to hire subcontractors from any nation friendly to Spain.

- 1662–1669: Grillo and Lomellini promised to ship 24,000 enslaved people in seven years. They were helped by the Dutch West India Company and the English Royal Adventurers. They brought enslaved people from Jamaica to Cartagena, Veracruz, and Portobello. In 1664, the political situation in Europe and the Caribbean was unstable, leading to the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Robert Holmes captured a Dutch trading post and ships. The Duke of York, governor of the Royal Africa Company, wanted to take over the Dutch trade of enslaved people to Spanish America.

- In 1664, the attorney general of Havana asked for a license to sail directly to Guinea and Angola to get enslaved people, instead of relying on those brought from Barbados and Curaçao.

- In 1667, Grillo and Lomellini convinced the Council of the Indies to return money to the Asiento to restart slave trade talks with the British and Dutch.

- Grillo and Lomellini contacted Francesco Ferroni in Amsterdam and then turned to the Dutch to fulfill their contract. Grillo's monopoly was not popular in the colonies. He mostly worked through others. In 1668, when Grillo faced financial problems, he got a two-year extension for the Asiento.

- In 1668, a large warehouse was built on Curaçao. About 90% of the enslaved people were exported from Curaçao, and half of them illegally.

- In 1669, Spain was almost bankrupt. The Coymans bank in Amsterdam transported Spanish silver to Cadiz to get a subcontract. King Charles II of England also tried to get the Asiento.

- The Treaty of Madrid (1670) was very good for England. Spain confirmed England's ownership of Caribbean territories. England agreed to stop piracy, and Spain allowed English ships freedom of movement. Both agreed not to trade in each other's Caribbean territories.

- In 1671, the Grillo Asiento ended due to mistrust. Grillo's experience opened the way for Dutch, English, and French slave trading companies to expand.

- In 1671, the privateer Henry Morgan, licensed by the English government, attacked and burned Panamá Viejo. This was an important port used by Grillo for the slave trade.

- In 1672, the Royal Africa Company was founded, led by the Duke of York.

- In 1673, the Compagnie du Sénégal was founded and used Gorée to house enslaved people.

- In 1674, the French West India Company went bankrupt. The Dutch lost New Amsterdam in the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

- In 1675, the Dutch New West India Company restarted. Curaçao became a free port for sugar, enslaved people, and illegal goods.

Dutch & Portuguese Asiento Holders: 1671–1701

In 1661, the Dutch and Portuguese signed a peace treaty. In 1667, the Dutch and English signed the Treaty of Breda, and New York became British. The Treaty of Lisbon (1668) ended twenty-eight years of war between Spain and Portugal. In the same year, France ended its war with Spain.

- 1671-1674: António Garcia, a Portuguese merchant, was the heir of Lomelino. In 1675, he sought help from Balthasar and Joseph Coymans and the Dutch West India Company. They helped finance the loan and shipping. Garcia arranged to buy all the enslaved people in Curaçao.

- 1676–1679: Manuel Hierro de Castro and Manuel José Cortizos. The Spanish wanted to get enslaved people from Cape Verde, but this went against the Dutch West India Company's rules. The Dutch offered to bring enslaved people to Hispaniola or other Spanish ports. From 1662 to 1690, only twenty slave vessels sailed under the Spanish flag.

- In May 1679, the Coymans financed slave transports, organized by Captain Juan Barroso del Pozo. They brought 9,800 enslaved people to Curaçao.

- In 1680, Barroso from Seville and Nicolás Porcio became Asentistas.

- 1682–1688: Juan Barroso del Pozo and Nicolás Porcio got the Asiento for 6.5 years. Porcio faced many financial problems after losing ships and enslaved people. In 1683, he traveled to Portobelo but was taken prisoner. He couldn't make his payments to the crown, claiming that local authorities in Cartagena were working against him.

- In 1683, Dutch privateers attacked Veracruz and Cartagena.

- In 1684, Genoa was heavily attacked by a French fleet for its alliance with Spain. As a result, Genoese bankers and traders made new financial connections with Louis XIV.

- 1685–1687: Balthasar Coymans managed to remove Porcio. The cash payment to the Spanish government was provided by Coymans' company in Amsterdam. Coymans made an immediate payment for Spanish navy ships being built in Amsterdam. He also paid an advance on the taxes he would owe for goods imported to Spanish America.

- In 1685, a Royal Order commanded Don Balthasar Coymans, Don Juan Barrosa, and Don Nicolás Porzio to gather ten Capuchin monks. These monks were to sail to Africa to buy enslaved people, convert them to Christianity, and sell them in the West Indies.

- In 1686, the Imperial Cortes started an investigation into the Asiento's legality. The Asiento with Coymans was canceled.

- In October 1686, the Dutch refused to accept the "Junta de Asiento de Negros," a commission with questionable authority.

- There was a risk of war between France, Britain, and Spain, leading to the Grand Alliance. The Dutch worried that Jamaica was becoming more important than Curaçao.

- The Dutch West India Company paid high dividends (10%).

- 1687–1688: Jan Carçau, a former assistant of Balthasar Coymans, took over the Asiento.

- In March 1688, Jan Carçao was imprisoned in Cádiz, accused of fraud. In June 1688, a commission stated that the Dutch must recognize the Junta's authority before discussions could continue.

- In August 1688, the shares of the Dutch East and West India companies dropped sharply on the Amsterdam stock market.

- 1688–1691: Nicolás Porcio.

- 1692–1695: Bernardo Francisco Marín de Guzmán.

- 1695–1701: Spain returned to the Portuguese. Manuel Ferreira de Carvalho represented the Cacheu and Cape Verde Company.

- By 1695, the French Navy had weakened and could no longer face the English and Dutch in open sea battles. They switched to privateering.

- 1695-1696: The Royal Africa Company suffered heavy losses and lost its monopoly after the Trade with Africa Act 1697.

- By 1696, it was clear that Charles II of Spain would die without children. His possible heirs included Louis XIV and Emperor Leopold.

- In May 1697, the French raided Cartagena and looted the city. Jean du Casse, who preferred an attack on Portobelo, gave his support reluctantly. All countries needed to boost their economies at the end of the Nine Years War. In September 1697, France signed peace treaties with Spain and England, and a trade treaty with the Dutch Republic. In the Caribbean, France received the Spanish islands of Tortuga and Saint-Domingue.

- 1699-1703: Manuel Belmonte worked with Luis and Simon Rodriques de Souza from the Portuguese West India Company.

- In 1700, a grandson of Louis XIV became King Philip V of Spain.

- In 1702, the War of the Spanish Succession began. The Grand Alliance (England, Dutch Republic, and Holy Roman Empire) declared war on France and Spain. Spanish naval losses meant they depended entirely on the French navy to communicate with the Americas. Spain relied on French ships not only for enslaved people but also for its silver fleet. Paying the French and Spanish for the Asiento was a major issue during the war.

- The Methuen Treaty regulated trade relations between England, Portugal, and possibly Brazil. The Portuguese had trouble giving up their Asiento rights.

French Asiento Holders: 1701–1713

- 1701–1713: Governor Jean-Baptiste du Casse, on behalf of the Compagnie de Guinée et de l'Assiente des Royaume de la France. This company focused on the slave trade for Guinea and Saint-Domingue, returning with sugar and other goods to Nantes. In 1701, the French King granted the Guinée Company the Spanish Asiento. The company reorganized and included both the Spanish and French Kings as shareholders. The Asiento did not involve the French Caribbean but Spanish America.

- In 1706, English planters on Jamaica asked the Guinée company to supply them with enslaved people, but this was refused.

- In 1711, Jacques Cassard led a French squadron that attacked and looted the Portuguese colony of Cape Verde. He then went to Montserrat and Antigua in the Caribbean before heading to Dutch possessions. In 1712, Cassard attacked Suriname and Berbice, demanding a large sum of money, which was paid in bills, enslaved people, and goods. Cassard returned to Martinique and then attacked Sint Eustatius. Curaçao was occupied by Cassard for a short time in 1713.

- The King ended the Asiento Company's monopoly in 1713. He opened the trade south of the Sierra Leone River to French private traders from five specific port towns. They paid a tax to the king for each enslaved African transported to the French West Indies.

British Asiento Holders: 1713–1750

After the Trade with Africa Act 1697, the Royal African Company lost its monopoly and became financially unstable in 1708.

- 1713–1743: The South Sea Company received the Asiento for thirty years. The English company had to pay 200,000 pesos to Philip for their share in the trade. This was to be paid in two equal parts. The company was also allowed to send one ship of 500 tons annually to Portobello for general trade, to prevent illegal trade.

The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 gave Britain the Asiento de negros for 30 years. This meant supplying the Spanish colonies with 144,000 enslaved people, at a rate of 4,800 per year. Britain could open offices in Buenos Aires, Caracas, Cartagena, Havana, Panama, Portobello, and Vera Cruz. An extra clause allowed one ship of no more than 500 tons to be sent to one of these places each year with general trade goods. One-quarter of the profits were to go to the King of Spain. The Asiento was granted in the name of Queen Anne and then given to the South Sea Company.

The company had to report its activities every five years. At the end of the contract, they had three years to remove their goods and settle their accounts.

By July, the South Sea Company had made agreements with the Royal African Company to supply the necessary enslaved Africans to Jamaica. They paid £10 for an enslaved person over 16 and £8 for one between 10 and 16. Two-thirds were to be male, and 90% adults. In the first year, the company shipped 1,230 enslaved people from Jamaica to America. When the first shipments arrived, local authorities refused to accept the Asiento because it hadn't been officially confirmed by Spanish authorities there. The enslaved people were eventually sold at a loss in the West Indies.

In 1714, the government announced that a quarter of profits would go to Queen Anne and another 7.5% to a financial advisor. Some company board members refused these terms, and the government had to change its decision. Despite these problems, the company continued, having raised 200,000 pesos to fund its operations. Queen Anne had secretly negotiated with France to get its approval for the Asiento. She proudly told Parliament of her success in taking the Asiento from France, and London celebrated this economic victory.

The South Sea Company's smuggling activities were a big concern for the Spanish. They invested heavily in naval protection. While this reduced the Asiento's profitability, increased Spanish monitoring helped detect more smuggling. An import duty of 33 pieces of eight was charged on each enslaved person (two children counted as one adult). In 1718, a war between England and Spain stopped Asiento operations until 1721. The company's assets in South America were seized, costing the company an estimated £300,000. Any hope of profit from trade disappeared. Similar conflicts interrupted the contract from 1727 to 1729 and 1739 to 1748. As more was learned about the company's illegal trading, Spain tightened its monitoring in the Americas in the 1730s. Spain then sought payment for the illegal trade carried out by the company. The issue was finally settled in 1750 when Britain agreed to give up its claim to the Asiento for a payment of £100,000 and favorable trade conditions with Spanish America. In 1752, the African Company of Merchants was founded.

It's estimated that the South Sea Company transported over 34,000 enslaved people. The death rates were similar to its competitors. Meanwhile, the slave trade became a business for privately owned companies. The Dutch West India Company began to outsource the slave trade in the 1730s. In 1740, a Havana company paid Spain for the Asiento to import enslaved people to Cuba.

- There was no Asiento during the Austrian War of Succession (1740-1748).

- 1748-1750: Spain renewed the Asiento with Britain for four years, but it ended with the Treaty of Madrid (1750). The Spanish authorities returned the slave trade to their own internal laws. By the mid-1700s, British Jamaica and French Saint-Domingue had become the largest slave societies in the region. By 1778, the French were importing about 13,000 enslaved Africans to the French West Indies each year.

- In 1762, the British imported more than 10,000 enslaved Africans to Havana. They used Havana as a base to supply the Caribbean and the southern Thirteen Colonies. In response to the short British occupation of Havana (1762–1763), when the British brought 3,500 enslaved people in ten months, the Spanish crown tried to restart its own transatlantic slave-trading role. Spain theoretically did not allow foreigners to directly share in colonial trade. This resulted in the colonies lacking necessary imports and encouraged smuggling.

Spanish Asiento Holders: 1765–1779

The Asiento was given to a group of Basques from 1765 to 1779.

- 1765–1772: Miguel de Uriarte, on behalf of Aguirre, Aristegui, J.M. Enrile y Compañía, or the Compañía Gaditana.

- 1773–1779: Aguirre, Aristegui y Compañía, or the Compañía Gaditana.

- A severe financial crisis in 1772 caused several bankers and their firms to go bankrupt. In 1773, many planters in Suriname and the Caribbean faced financial trouble, and the Dutch slave trade dropped.

- A major moral victory happened when the British Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, ruled in 1772 that slavery was illegal in Britain. This freed about 15,000 enslaved people who had come with their masters.

- During the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, the English seized some Dutch slave ships. An attempt to capture the Dutch castle at Elmina in Africa failed in 1782. While many Dutch territories in the West Indies were taken by the British, some, like Curaçao, were not attacked because they were well-defended.

- In 1784, the Spanish crown contracted with a large Liverpool firm to bring enslaved people to Venezuela and Cuba between 1786 and 1789.

- On February 4, 1794, a decree was passed by the National Legislative Assembly, making France the first European country to officially outlaw slavery in all its colonies. However, this was only put into practice in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Guiana.

- In March 1795, the Batavian Republic did not treat all citizens equally.

- The Law of May 20, 1802, brought back slavery in the French Empire.

Spain's involvement in the slave trade from Africa was small compared to Portugal, England, France, and the Netherlands. It's estimated that Spain made only 185 voyages and transported 276,885 enslaved people from 1500 to 1800. This is much less than the almost 25,000 voyages and over 7,331,831 enslaved people transported by those other nations during the same period. Of the total number of enslaved people, nearly half went to the Caribbean islands and the Guianas, about 40% to Brazil, and about 6% to mainland Spanish America. Most arrived between 1601 and 1625, but the number dropped to its lowest between 1676 and 1700. Less than 5% of the enslaved people went to North America. These numbers might change as new research suggests half went to Brazil and a quarter to the Caribbean.

See also

In Spanish: Asiento (economía) para niños

In Spanish: Asiento (economía) para niños