Benalla Migrant Camp facts for kids

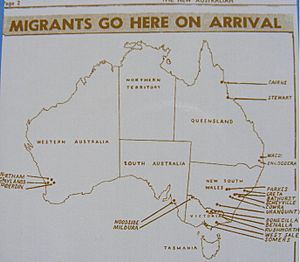

The Benalla Migrant Camp was a special place in Benalla, Australia. It was also known as the Benalla Holding Centre or the Benalla Migrant Accommodation Centre. After World War II, the Australian government set up 23 camps like this. Their purpose was to give temporary homes to new people arriving in Australia who were not from Britain.

The Benalla camp opened in 1949 and stayed open until 1967. It provided housing for many families, including single mothers and their children. Over 60,000 people lived there during its time. Most of them came from countries like Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Germany, and Estonia. For many years, the camp site was forgotten. But in 2016, it was officially recognized and listed as an important historical place.

Contents

What Was the Benalla Migrant Camp Like?

The Benalla Migrant Camp was first meant to be a "holding centre." This meant it offered short-term homes for families of new arrivals. These new Australians, mostly from central and eastern Europe, came as part of a big plan. Australia wanted to grow its population and workforce after the war.

New migrants had to agree to work in jobs chosen by the government. If the main earner in a family found work far away, their family would stay at a holding centre like Benalla. This system often meant families were separated, which many people criticized. The camp was also special because it had childcare. This allowed mothers to work, which was very unusual for that time.

Camp Buildings and Facilities

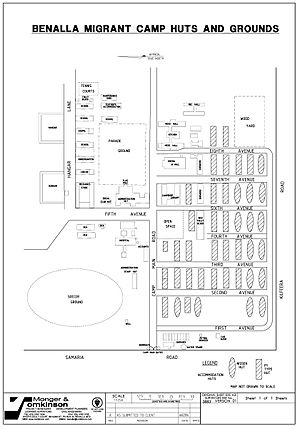

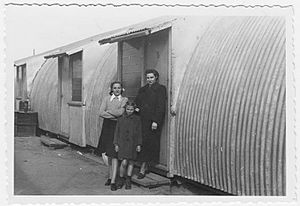

The homes at Benalla were simple huts made of corrugated iron. These were called 'P-type' huts and were originally used by the military. At first, they had no inner lining or power points. There were separate buildings for cooking and washing. The camp also had a kindergarten, a school, a hall, a hospital, shops, and a gym. Later, more huts called Nissen Huts were added to fit more people.

While living at the camp, residents had medical checks. They also took classes to learn English and about the Australian way of life. Most people were expected to stay for about four to six months. Some stayed longer, even up to 15 years, especially if they had a two-year work contract with the government. Residents had to pay a fee for their accommodation.

History of the Camp

The Benalla Migrant Camp was built on the site of a former air force training school. This school, called No.11 Elementary Flying Training School, was used by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) from 1941 to 1944. The camp was located next to a small airfield outside Benalla in north-east Victoria.

The camp opened in September 1949. It started as a small centre, housing between 200 and 400 people. The busiest time was in the early years. In 1951, it had its highest number of residents, with 1,063 migrants. The number of new arrivals slowed down after 1952, and some other holding centres closed.

Changes and Closure

In 1953, the rules for the camp began to change. Benalla was no longer just for family members. In 1958, its name officially changed to the Benalla Migrant Accommodation Centre. The facilities were improved. It started to house main earners and their families if they worked in the Benalla area and could not find other homes.

Even though the camp could hold 500 people, about 400 residents lived there through the 1950s. Around 200 people moved in and out each year. The camp continued to operate even after national reviews in 1953 and 1959. By the mid-1960s, fewer than 250 people lived there. In 1967, only 135 residents remained. An official review found it was too expensive to keep open. The camp closed on December 8, 1967.

After the camp closed, the airfield was still used for planes and recreation. Many of the old camp buildings were taken down in the 1980s. The Benalla City Council bought the land in 1992.

The Benalla Experiment

The Benalla Holding Centre had a special role in Australia's migrant camp system. It took in single mothers with children. These women were often called "unsupported mothers" or "widows and unmarried mothers" at the time. Australia's immigration plan allowed many of these mothers to come. This was a kind act to help the International Refugee Organization empty the Displaced Persons Camps in Europe. The Minister for Immigration, Harold Holt, knew it would be a challenge to find them jobs and homes.

From late 1951, many of these single mothers were sent to the Benalla Holding Centre. The camp was close to two new factories: Latoof and Callil (a clothing factory) and Renold Chains. These factories offered jobs to the women. Some women also worked at the camp as cooks, cleaners, or in the office. Others found jobs locally as housekeepers.

Challenges for Single Mothers

About one-third of the people living at the Benalla Migrant Camp were single mothers. At first, this idea, sometimes called the "Benalla experiment," seemed to work well. Especially after the camp facilities improved and good childcare was provided. Women received English language training and classes on how to run a home. This was meant to help them get married and fit into the wider community. Benalla was only supposed to be a short-term solution for these women. With 30-50 residents moving out each month, the system seemed fine at first.

However, the jobs available to these mothers did not pay enough. They could not save enough money to buy their own homes. For most of these women, the best way to leave the camp was to get married. Or, they could move in with their oldest child once that child started working and could set up a home. But if these chances did not happen, there was a problem.

Living in temporary conditions for a long time was hard on both the women and their children. By 1956, many social workers found that Benalla had many "long stayers." These were people who had little hope of leaving. Some were even afraid to leave the safety of the camp.

When the camp closed in 1967, a social worker named Mrs. K. Patterson was asked to help. She was to suggest ways for the remaining residents to join the community. One former social worker later said that the "Benalla experiment" was not a success. She called Benalla a "sad and tragic camp" where single mothers were sent. She noted that the women's spirits were low, and they struggled to fit into the community.

Becoming a Heritage Site

On May 19, 2016, the Benalla Migrant Camp was officially listed as an important historical site in Victoria. Historian Bruce Pennay said two main things led to this listing. First, a local resident named Sabine Smyth created an exhibition about the camp. Second, there were plans to redevelop the airport nearby, which could have put the site at risk.

In 2012, Sabine Smyth started collecting names, memories, old items, and photos from the camp. She wanted to create a photo exhibition for Australia Day in 2013. The Benalla Migrant Camp Exhibition was held in Hut 11, one of the old camp huts. In April 2013, a volunteer group called Benalla Migrant Camp Inc. was formed. Their goal was to keep collecting historical materials and create a permanent exhibition. The exhibition is still open to visitors regularly. Sabine Smyth continues to gather photos and stories from people who used to live at the camp.

The Listing Process

In January 2014, Sabine Smyth's group applied to have the former RAAF base and migrant camp listed as a heritage site. It was first rejected but then accepted on March 7, 2014. Separately, a heritage expert named Deborah Kemp also looked at the site. She was working for Benalla Rural City as part of the Benalla Airport Redevelopment Plan. This plan was for the World Gliding Championships held at the site in 2017. She found the site was important locally and likely at the state level too.

She noted that most of the original camp had been taken down or sold. This was to make space for an aged care facility. However, nine of the original P-type huts still remained. Six buildings were still in their original spots. These included two toilet blocks and four huts. Two of these huts were school buildings. One served as the camp chapel, and another was likely the crèche or kindergarten. Other old parts still there included concrete gate posts, an old underground water tank, and the road called BARC Avenue.

In 2015, a petition was started to save the camp's remains. This helped encourage Heritage Victoria to check the site's historical value in July 2015. At first, they suggested the site should not be added to the Victorian Heritage Register. They felt that the history of post-WWII migration was clearer at the larger camp in Bonegilla and at the former Maribyrnong Migrant Hostel.

Final Decision

In February 2016, Heritage Victoria held a meeting in Benalla to discuss this suggestion. About 100 community members attended over two days. They heard 18 statements that disagreed with the suggestion. Because of this, they decided the site was important and should be added to the state Heritage Register (VHR Number H2358).

The site was considered important at a state level for several reasons. It is one of the few remaining post-World War II migrant centres for non-British people. It was also Victoria's longest-lasting holding centre. It played a special role in helping vulnerable groups of non-British migrants settle after the war. It was also seen as socially important because of its connection to former residents and their families. It helps explain the experiences of non-British migrants after World War II to the wider community in Victoria.

Historian Bruce Pennay has called the Benalla Migrant Camp a site with a "difficult heritage." This is partly because it does not easily fit into the happy stories of migrant success that are often told about Australia's history. Pennay believes that all holding centres "raise uncomfortable questions." These questions are about the difficult policies of family separation, forced movement, trying to make people fit in, and whether there were enough support services.

The site is owned by the Benalla Rural City Council. A plan for its care and protection is currently being developed. The Benalla Migrant Camp Exhibition in Hut 11 continues to receive strong support from the community. Especially from former camp residents and their families, who now live all over Victoria, Australia, and the world.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |