Butler Island (Georgia) facts for kids

Butler Island is a 1,600-acre island located in the Altamaha River in McIntosh County, Georgia, United States. It's part of the Altamaha River Delta. The island is about 1 mile (1.6 km) south-southeast of Darien, Georgia.

The Altamaha River splits into different branches in this delta area. The northern branch, called the Butler River, is about 3.1 miles (5 km) long and flows north of Butler Island, which is shaped like a boomerang. Major highways, Interstate 95 and US Route 17, cross different parts of Butler Island. US Route 17 connects the island to General's Island and Darien.

A well-known landmark on the island is a 75-foot (23 m) tall brick chimney. This chimney is what remains of the rice mill from the old Butler Island Plantation.

Contents

A Famous Owner

Butler Island is named after its first owner, Major Pierce Butler (1744–1822). He was an important figure in early American history, known as a Founding Father. He also served as a U.S. Senator for South Carolina.

Major Butler was originally an officer in the British Army. He came to the American Colonies in 1768. In 1771, he married Mary Middleton, whose family owned many enslaved people in South Carolina. Butler later joined the American side during the Revolutionary War. He was a delegate for South Carolina at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. There, he strongly supported slavery. He served in the U.S. Senate from 1789 to 1796, and again from 1803 to 1804.

Plantations in Georgia

After his wife died in 1790, Major Butler sold his properties in South Carolina. He then invested in large plantations on the Sea Islands of Georgia. He moved enslaved people from South Carolina to work on these new plantations. Later, he bought more enslaved people from Virginia and West Africa. The West Africans had experience growing rice.

In the early years, cotton was the main crop grown on St. Simons Island. But as the soil there became less fertile, rice became the most important crop on Butler Island.

Roswell King managed Major Butler's Georgia plantations from 1802 to 1819. In 1803, he counted 540 enslaved people by name. He also rated their ability to work. Most plantations had a white overseer. Under him, a trusted Black "headman" or "driver" helped manage the work. At its busiest, the Butler Island Plantation had a white overseer, a Black "head driver," and four "drivers."

Major Butler was very strict. He managed the enslaved people on his plantations with military-like rules. His plantations were very organized. Everything needed, from shoes and clothes to furniture and tools, was made on the plantation.

In January 1815, during the War of 1812, British Admiral George Cockburn sailed into the Altamaha River. He offered freedom to the enslaved Africans held by Major Butler on St. Simons Island. About 138 of them accepted his offer. The British Navy took these newly freed people to Nova Scotia. They were given the last name "Butler."

Major Butler became the largest slaveholder in coastal Georgia. He owned around a thousand enslaved people. He had three plantations: Hampton on St. Simons Island, Butler Island, and Woodville. Woodville was used to grow corn and raise animals for the other plantations.

Hampton was about 10 miles (16 km) downstream from Butler Island. The Butler Island and Hampton plantations worked together. About 60% of the enslaved people lived in four settlements on Butler Island. Growing rice was harder work than growing cotton. So, the workforce on Butler Island was generally younger and stronger. Because of the risk of malaria, pregnant women, many children, older workers, and sick people lived at Hampton. Hampton was thought to be a healthier place. Between 1819 and 1834, more than half of the children on Butler Island died before age six.

Roswell King, Jr. took over managing the Butler plantations from his father. He managed them from 1819 to 1838, and again from 1841 to 1853. When Major Butler died in 1822, he owned 638 enslaved Africans on his Georgia plantations.

Growing Rice

Rice was grown in special fields that could be flooded with water. This needed careful control of fresh water to get the best harvest. Dikes were built around these fields to keep out the salty river water during high tide.

In coastal Georgia, rice was usually ready to harvest in late August. At this time, the grains were starting to get hard. The flooded fields were drained. Workers used small sickles to cut each rice stalk at its base. The stalks were tied into bundles and stacked to dry. After drying, the stalks were cut away. The dried rice was boiled, then dried again. It was then threshed to separate the kernels from the outer husks.

Next, the kernels were pounded using wooden tools called mortars and pestles. This loosened the hard outer coating, called hulls. The pounded kernels were then carried in woven baskets up a ladder into a "winnowing barn." This was a small building on tall stilts. The pounded kernels were dropped through a trap door in the floor. The wind would blow away the light hulls, while the heavier brown rice fell to the ground. The brown rice was then "polished" into white rice. This was done by soaking it to loosen the bran, which is a thin inner coating. The wet brown rice was then kneaded until the bran and germ separated from the white grain.

Pounding the rice with mortars and pestles was the most tiring part of the work. To make this easier, Roswell King tried to build a pounding mill in 1803. This mill was supposed to be powered by the river's tides. But building a strong base in the soft soil was hard. Also, the mill could only work when the tides were moving, which made it less efficient. By 1816, a water-powered mill was working. It had two pounding machines for the rice kernels. However, "All phases of producing the rice crop, except the pounding, were done by hand."

The Steam Mill

In 1832, the decision was made to build a steam-powered mill. Roswell King Jr. had wooden poles driven into the highest part of Butler Island. This was the plantation yard next to the Butler River landing. These poles were to support the heavy 14-horsepower steam engine and its brick chimney. The mill was finished in December 1833.

However, the new mill created problems in the production line. The steam engine could pound and polish rice much faster than workers could thresh and winnow it by hand. None of the threshing workers could keep up. The steam engine had to be shut down often to give them a break. Also, winnowing needed wind to blow away the hulls. So, the steam engine sat idle on days without wind. The workers who made barrels to pack the processed rice also fell behind. The steam engine needed a lot of wood for fuel, so more pine forests had to be bought. The workers did not like the steam engine. One visitor described it as creating "a perpetual monotonous burden."

The Butler Family

Major Butler did not leave his property to his only surviving son, Thomas. Instead, he wanted his daughter Sarah Butler Mease's sons to be his heirs. But they had to legally change their last names to "Butler." Her younger son, Pierce Mease (1810-1867), changed his name to Pierce Mease Butler in 1831. Her older son, John A. Mease (1806-1847), also changed his name to "Butler" in December 1831. Each of them inherited half of Major Butler's plantations and enslaved people.

Pierce Mease Butler

Pierce Mease Butler married British actress Fanny Kemble in 1834. She and their two young daughters spent their first winter with him on Butler Island in 1838. Kemble hoped to convince Butler to stop owning enslaved people, but she was unsuccessful. She wrote about her experiences with slavery in her memoir, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839. The couple separated in 1847, and Butler divorced Kemble in 1849. He prevented her from seeing their daughters for several years.

John A. Butler died in 1847. In his will, he said his share of the Georgia plantations should be sold. However, his brother Pierce and his widow Gabriella actually used his estate to buy more land. In August 1853, Pierce and John A. Butler's estate together bought the nearby 700-acre plantation on General's Island.

By 1844, the Butler Island rice mill was producing up to a million pounds of processed rice each year. With the addition of the General's Island plantation, the mill's output increased to two million pounds per year in the mid-1850s.

The Great Slave Auction

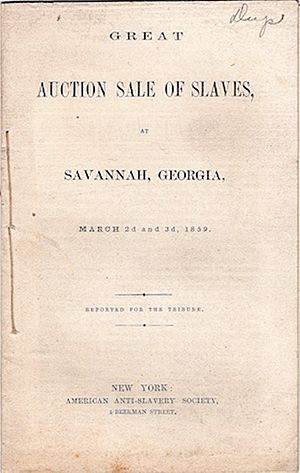

Pierce Butler lost a lot of money, but he avoided bankruptcy by selling his half of the enslaved people on the plantations.

The Great Slave Auction took place on March 2–3, 1859, at the Ten Broeck Race Course near Savannah, Georgia. Butler sold 436 enslaved Africans. This was the largest single sale of enslaved people in American history. Most of the enslaved people were brought by train, but some traveled by steamboat from Darien to Savannah. They were all housed in the racetrack's stables. People interested in buying were allowed to inspect them for four days before the auction. The enslaved people were sold in family groups of two to seven people. The sale brought in $303,850, which was an average of over $708 per person.

Mortimer Thomson, a reporter for The New York Tribune, pretended to be a bidder. He questioned the enslaved people and attended both days of the auction. His detailed report was published in the Tribune on March 9, 1859. It caused a huge stir and was reprinted in other Northern cities and as a pamphlet.

The sale helped Pierce Butler pay off most of his debts. The 1860 U.S. Census showed 505 enslaved Africans still living on Butler Island. These were all the property of John A. Butler's estate.

Civil War

Pierce Butler stayed in Philadelphia during the American Civil War. He was in Georgia when the war began in April 1861. He returned to Philadelphia in August. He was accused of treason and held at Fort Hamilton in New York City for a short time in 1861.

In February 1862, the Union Navy blocked the Altamaha River. They also took control of St. Simons Island and Butler Island. In June 1863, two regiments of U.S. Colored Troops landed on St. Simons Island. One of the commanders ordered his regiment to loot the deserted town of Darien. After looting, Darien was burned to the ground.

The enslaved Africans on the Butler plantations gained their freedom in 1863, thanks to the Emancipation Proclamation. The military stayed on Butler Island and St. Simons Island until 1866.

After the War

Pierce Butler's daughters, Sarah and Frances (Fan), had different views on slavery. Sarah shared her mother's anti-slavery views. Fan was close to her father and supported his views on slavery.

Pierce Butler and his daughter Fan returned to Georgia in March 1866 to reclaim the plantations. Fan wrote that all the enslaved people who had belonged to John A. Butler's estate were still on the properties. Seven of those who had been sold in 1859 also returned. The formerly enslaved people agreed to work as sharecroppers. This meant they would share the rice crop, 50-50, with the owners. Pierce Butler promised to support the elderly until they died and to support young children for three years.

Pierce Mease Butler died in Georgia in August 1867.

Frances Butler Leigh

Fan Butler took over managing the plantations. About 300 workers tended the rice on Butler Island. About 50 workers tended the cotton on St. Simons Island. Her contracts with the formerly enslaved workers needed approval from the Freedmen's Bureau. She paid workers $12 per month, plus food, clothing, and shelter. She turned an existing building on Butler Island into a school, infirmary, and church. She hired a Black graduate from a Pennsylvania seminary to be the instructor and minister.

An English cousin, Rev. James Wentworth Leigh, visited Butler Island in November 1869. Fan Butler and her sister visited him in England the next summer. Fan Butler and Rev. Leigh got engaged in December and married in England in June 1871. The Leighs stayed in England until they returned to Georgia in Autumn 1873.

While Fan Butler was away, the rice mill, steam engine, and other buildings were destroyed in a fire. It was believed to be arson. This fire destroyed about fifteen thousand dollars' worth of property, including all the seed rice for the next planting season. The Leighs returned to Butler Island in November 1873 and rebuilt the mill.

Rev. Leigh held church services for the free Black workers in the school. These services led him to start a new African-American Episcopal church in Darien in 1875. Frances Butler Leigh donated town lots she inherited from her father for the church. The church members built St. Cyprian's Episcopal Church, which was dedicated in 1876.

Rev. and Mrs. Leigh returned to England in January 1877.

Sarah Butler Wister's son, the novelist Owen Wister (1860-1938), inherited his mother's half of the plantations. He was the last family member to own land on Butler Island. He sold the last of the properties in 1923.

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |