Civil Resettlement Units facts for kids

Civil Resettlement Units, or CRUs, were special places set up after World War Two. They were created by doctors from the Royal Army Medical Corps to help British Army soldiers. These soldiers had been prisoners of war (POWs) and needed help getting back to normal life. The CRUs also helped their families and communities welcome them home.

Units started opening across Britain in 1945. They first helped soldiers held captive in Europe. Later, they also helped POWs from the Far East (FEPOWs). By March 1947, over 19,000 European POWs and 4,500 FEPOWs had visited a CRU.

Contents

Why Were CRUs Needed?

During the First World War, many experts thought that soldiers who became prisoners were safe from mental harm. They believed being away from the fighting protected them. This idea was linked to the belief that shell shock (a type of trauma) was a way to escape danger.

Around World War Two, this view began to change. Doctors like Millais Culpin and Adolf Vischer argued that POWs could suffer mental harm. Vischer even called this "barbed-wire disease." Doctors wanted to study these ideas, and the war gave them the chance. The 1929 Geneva Convention also changed how POWs were treated. It allowed for prisoner exchange, meaning POWs could return home before the war ended.

In September 1943, Lieutenant General Sir Alexander Hood held a meeting. They discussed how to bring POWs home. It was decided that British Army doctors should look into problems POWs might face. They also needed to figure out how to help them. A group called the "Invisible College" led this work. They later formed the Tavistock Institute after the war.

Early Ideas for Helping POWs

Doctors tried different ways to help soldiers. Some of the earliest ideas came from military hospitals and special army units.

Northfield Military Hospital

POWs with the most serious problems went to hospitals like Northfield Military Hospital. Doctors there noticed that patients often felt "resentful of everyone and everything." They worried these feelings could cause problems in society if many returning POWs felt this way.

No. 21 War Office Selection Board

Psychiatrist Major Wilfred Bion and psychologist Lieutenant Colonel Eric Trist worked at No. 21 War Office Selection Board (WOSB). This was at the Selsdon Court Hotel in Surrey. They tried to use officer selection methods to find POWs who could return to active duty. This "officer reception unit" aimed to give them advice on military training and jobs. Bion suggested that helping POWs should feel more military than medical. This way, the soldiers would not feel like they were being treated for mental issues.

The Crookham Experiment

Major A. T. M. "Tommy" Wilson, a psychiatrist, led an experiment. This was at No. 1 RAMC Depot in Crookham. The program helped medical staff who had been POWs. It ran from November 1943 to February 1944. About 1200 POWs took part in a four-week program.

POWs often had low spirits, missed work, got sick a lot, and had mental distress. The experiment's findings were published in a report called The Prisoner of War Comes Home. It said that most POWs were not mentally ill. Instead, they just needed support to adjust to life back home.

Setting Up Civil Resettlement Units

In March 1945, the War Office agreed to create 20 Civil Resettlement Units. In the spring of 1945, the CRU organizers quickly prepared for many POWs returning from Germany. They chose Hatfield House as the main CRU Headquarters. Other country houses across Britain were turned into CRUs. This allowed men to attend a unit close to their homes.

Choosing the Name

The team creating the CRUs thought carefully about the name. From earlier studies, army doctors knew that POWs were sensitive. They did not want to be seen as mentally "damaged." So, the Adjutant General Sir Ronald Adam gave official orders. He said that words like "rehabilitation" or "mental rehabilitation" should not be used.

One soldier who had been through a similar program also suggested changing the name. He said, "I would not call it a Special Training Unit to any man." He felt the word "training" should be changed. In the end, the planners decided to use "resettlement" or "resettlement training" instead.

Who Worked at a CRU?

Each CRU had a Commanding Officer and a Second-in-Command, who were military men. There was also a Medical Officer, usually a psychiatrist, though this was often kept quiet. Other staff included a Vocational Officer (for careers), a Ministry of Labour Liaison, and a Civil Liaison Officer. The Civil Liaison Officer was a social worker, usually a woman, trained in helping with mental and social issues.

Many other CRU staff were from the Auxiliary Territorial Service, which meant they were women. POWs might not have seen women for years. These women staff helped the returning soldiers feel more comfortable around women again.

The team at No. 1 CRU, the main headquarters, included Tommy Wilson as the head psychiatrist. Colonel Richard Meadows Rendel was the Commanding Officer. Psychologists Eric Trist and Isabel Menzies Lyth, mathematician Harold Bridger, and military officers Ian Dawson and Dick Braund were also part of the team.

What Happened at a CRU?

About 60 volunteers, divided into four groups of 15, arrived each week at a CRU. They listened to talks from the Commanding Officer and Medical Officer. After that, the program was mostly voluntary. The only required part was an interview when a soldier left the CRU.

Soldiers could attend workshops or visit nearby workplaces. They could also have short work experience placements. They had group discussions and met with the Vocational Officer to talk about jobs. They could also meet the Civil Liaison Officer to discuss social or relationship worries.

CRUs also held whist drives (card games) and dances. Local people came to these events. This helped civilians and returning POWs meet and get used to each other. The men did not have to wear their military uniforms, except for pay day.

Sharing Information About CRUs

To tell POWs about the program early, information was sent through the British Red Cross. Officers from the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force also shared details with POWs while they were still in camps.

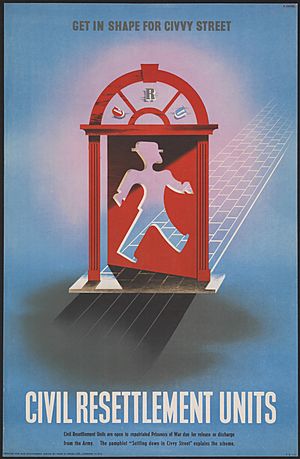

A leaflet called Settling Down on Civvy Street was given to POWs a week or two after they returned to Britain. This timing was chosen because the first excitement of being home might have worn off. At this point, POWs might start feeling frustrated or have questions.

Many local newspapers wrote stories about CRUs and the local men attending them. National newspapers also reported on the creation of the CRUs. On July 12, 1945, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited Hatfield. This visit created a lot of news coverage.

Who Attended the CRUs?

All the soldiers who went to the CRUs were volunteers. Those from earlier studies had been told by the Army to attend. However, they were due to leave the army once their course finished.

After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the War Office planned for CRUs to only accept Far East prisoners of war (FEPOWs). They thought the CRUs could not handle all POWs from Europe and the Far East. They also believed FEPOWs needed the service more.

However, Wilson and Rendel felt that European POWs should still have the chance to attend. They worked hard to expand the program and make space for both groups. Because of this, Rendel and Wilson were removed from leading the program. By the end of March 1947, over 19,000 European POWs and 4,500 FEPOWs had attended a CRU.

Did CRUs Work?

Major Adam Curle and Eric Trist studied how well CRUs worked. They found that only 26% of POWs who attended a CRU showed signs of "unsettlement." This was much lower than the 64% of POWs who did not attend a CRU. Curle and Trist also found that the "settled" men had better social relationships than a group of civilians. They believed this showed the CRU's value as a place for healing and community. However, they also noted that men who were already more "settled" might have been more likely to attend a CRU in the first place.

Some researchers, like Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely, have said that the study had a small number of participants. Also, it only looked at one location. This might limit how accurate the results are.

What Was the Legacy of CRUs?

The ideas and methods developed for the CRUs were later used to help European civilians who had lost their homes because of the war.

CRUs were one of the first controlled experiments in social psychology. The work done at the CRUs helped develop the idea of therapeutic communities. Many staff members from No. 1 CRU had also worked on the WOSBs. Their teamwork on these two programs led them to create the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in 1947.

The records of the Tavistock Institute, which include a lot of information about the CRUs, have been organized. They are now at the Wellcome Library and can be viewed there.

See also

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |