Confederate government of West Virginia facts for kids

On June 20, 1863, the United States government created a new state called West Virginia. It was formed from 50 western counties of Virginia. This happened with the approval of President Lincoln and Congress. However, not many citizens in the new state participated in the decision. Many people and counties still felt they were part of Virginia and the Confederacy. In 1861, these 50 counties had about 355,544 white people, 2,782 free Black people, and 18,371 enslaved people. There were 79,515 voters and 67,721 men old enough for military service. West Virginia was a very important place during the war, with 632 battles and small fights happening there.

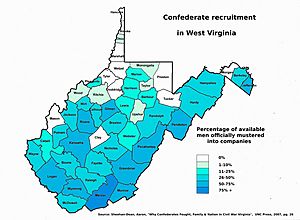

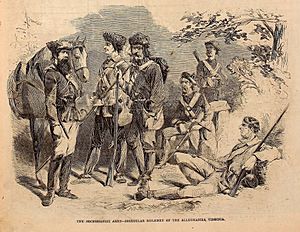

Even though the U.S. government saw West Virginia as a loyal Union state, about half of its soldiers joined the Confederate army. It was the only "border state" (a state between the North and South) that didn't send most of its soldiers to the Union. While the Union army controlled much of the new state, many areas were still held by small groups of fighters called guerrillas. The Union army stayed in West Virginia until 1869, dealing with unrest until 1868.

Contents

Why West Virginia Became a State

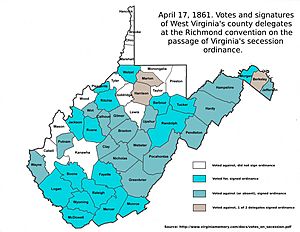

When the Virginia convention in Richmond voted to leave the United States on April 17, 1861, most delegates from the western counties (which became West Virginia) voted against it. Out of 49 delegates, 32 voted no, 13 voted yes, and 4 were absent.

After Union troops moved into western Virginia in May, some delegates who had first voted against leaving Virginia changed their minds. Many returned to the convention and signed the document to leave the Union. Some delegates were arrested, like Benjamin Wilson, or became refugees. Others joined the Confederate army.

Some delegates who didn't sign the secession document later had problems with the new Union-supporting government in Wheeling. For example, Sherrard Clemens spoke out against the new state. Marshall M. Dent was accused of treason. John Jay Jackson, Sr. called the new government "usurped." John Carlile, who had strongly supported a new state, tried to stop the statehood bill in the Senate but failed. He was later arrested for treason by President Lincoln. George W. Summers urged people to defend "old Virginia."

Feelings About Leaving the Union in West Virginia

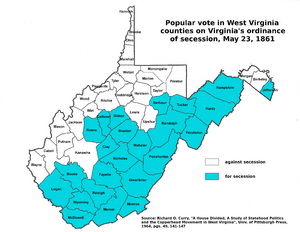

West Virginia was formed from three parts of Virginia: the Northwest, the Shenandoah Valley, and the Southwest. When Virginia considered leaving the United States, there was little support for it in the counties near Ohio and Pennsylvania. However, there was more support in the central and southern counties of what became West Virginia.

In January 1861, the first flag showing support for leaving the Union flew over the courthouse in Philippi, Barbour County. This flag was captured by Union soldiers in June 1861. Other flags supporting secession flew in Tucker County and Guyandotte. On May 14, the Confederate "stars and bars" flag was raised over the courthouse in Logan County.

Many people in the northwestern counties held meetings to support "Southern Rights." Even though many of these counties voted against leaving the Union, secessionists were active there. In total, 24 of the 50 counties that became West Virginia voted to leave the United States. These counties had 40% of the population and two-thirds of the land of the new state. The vote on May 23, 1861, showed about 19,000 to 20,000 people for secession and about 33,000 to 34,000 against it.

This meant a large part of West Virginia supported the Confederate government in Richmond. Union support in some border counties weakened when Union troops entered western Virginia in May 1861. In the northwestern counties, many men joined Confederate units. For example, Putnam County voted strongly against secession, but half of its soldiers joined the Confederacy. This also happened in Cabell, Kanawha, and Wayne counties. One reason for this was "state pride" and not wanting outside interference in Virginia's affairs.

County courts in several counties raised money to arm local militias to defend Virginia. When Governor Letcher called for militias, the counties along the northwestern border did not respond. However, militias in the southern and Valley counties mostly answered the call.

Important Confederate Leaders from West Virginia

Military Leaders

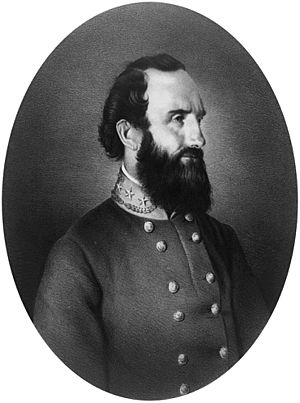

Sixteen Confederate generals were born or lived in West Virginia. Three of them led Virginia militias. The most famous general was Stonewall Jackson from Clarksburg. He became a Lieutenant-General before he died in 1863. He wanted to serve in western Virginia, but he was kept in the Shenandoah Valley. His famous "Stonewall Brigade" included many West Virginia volunteers.

Generals Albert G. Jenkins and William Lowther Jackson often led raids in West Virginia, looking for supplies and new soldiers. Jenkins died in battle in 1864. John McCausland became well-known for burning the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in 1864. John Echols led a regiment where half the men were from West Virginia. Edwin Gray Lee, a cousin of Robert E. Lee, also served and became a brigadier general.

Other important military figures included Christopher Q. Tompkins and George S. Patton (grandfather of the famous World War II general). They helped organize volunteers in the Kanawha Valley. Patton was killed in battle in 1864. Angus W. McDonald led a cavalry unit and helped defend bridges. Lt. Col. Vincent A. Witcher was a cavalry officer who fought in many battles, including Gettysburg. Hanse McNeill led a group of Rangers who operated in the Shenandoah Valley. After he died, his son Jesse took command and famously captured two Union generals.

Many West Virginia recruits served under John Imboden, who operated in West Virginia and was part of Lee's Gettysburg campaign. West Virginia volunteers joined many Confederate infantry and cavalry units, artillery batteries, and ranger companies. In total, about 20,000 to 22,000 West Virginians served the Confederacy.

Political Leaders

After Virginia voted to secede, they appointed delegates to the Confederate Congress. Gideon D. Camden was one, but he resigned because his home was behind Union lines. Other delegates from West Virginia counties included Charles Wells Russell, Robert Johnston, and Alexander Boteler. Boteler also served on Stonewall Jackson's staff. These politicians worked to strengthen the Confederate government and regain control of their districts.

Albert G. Jenkins left his military role to serve in the Confederate Congress but later returned to the army. Samuel Augustine Miller took his place and worked on army pay and clothing issues. Robert Johnston supported a strong central government and Jefferson Davis's power. Charles Wells Russell, whose district was mostly under Union control, was very active in Congress.

Allen T. Caperton from Monroe County became a Confederate senator and served until the end of the war. He later became a U.S. senator for West Virginia. Samuel Price from Greenbrier County became Lieutenant Governor of Virginia. He was concerned that Richmond wasn't doing enough to defend western Virginia. He was arrested by Union forces but was rescued.

Mason Mathews, a state senator, warned Jefferson Davis about conflicts between Confederate generals that hurt the defense of western Virginia. His son, Henry, later became a governor of West Virginia. After the war, President Lincoln asked the Virginia legislature to meet again. Samuel Price and Allen Caperton were arrested but later released and received pardons. One hundred and one West Virginians received special pardons for their roles in the Confederacy.

Confederate Mail and Money

Mail Service

Confederate post offices in West Virginia generally followed the line of counties that supported secession. They stretched from Harpers Ferry to southwest Virginia. There were at least 50 such post offices in towns like Shepherdstown, Martinsburg, and Lewisburg. Before official Confederate stamps were issued, postmasters would mark letters as "paid."

Some postmasters served both sides. The post office in Harpers Ferry closed when Confederate forces left in June 1861. The longest-serving postmaster was James A. Shanklin in Union, Monroe County, who served from 1821 to 1865. Many post offices opened or closed depending on which side controlled the area. After the war, five West Virginians who were "rebel postmasters" received special pardons from President Andrew Johnson.

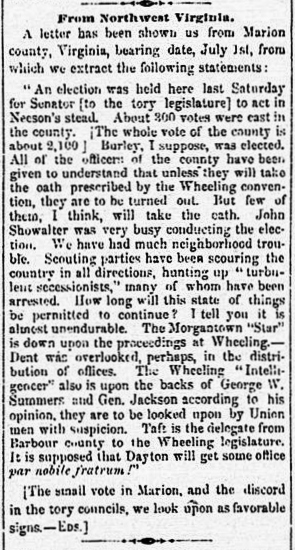

Confederate mail carriers operated in various counties. A route ran from Parkersburg to Calhoun County. Sometimes, Confederate mail was secretly put into the Federal mail system by sympathetic postmasters. However, suspicious mail was sometimes opened by Federal authorities, leading to arrests. In central West Virginia, the ongoing guerrilla war disrupted both Union and Confederate mail services. Women often carried mail informally through Union lines because they were less likely to be searched.

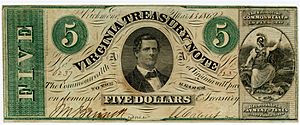

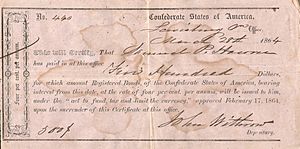

Money

Confederate money was mostly used in the eastern and southern counties of West Virginia. Confederate officers often used it to pay for goods during raids. Many Virginia notes had a picture of Jonathan M. Bennett, the state auditor, who was from Lewis County. Confederate bonds were also issued. The paychecks of West Virginia's Confederate soldiers would have brought a lot of this money into the state.

In 1863, Dr. Thomas B. Camden sold his horse for $140 in Confederate money before he was imprisoned. After the war, legal cases about using Confederate money to pay debts or buy land lasted for many years. In 1873, a state law said that Confederate money used in contracts from 1861-1865 had to be valued at its true worth at the time of the contract. In areas controlled by the Union army, many merchants didn't want to accept Confederate money.

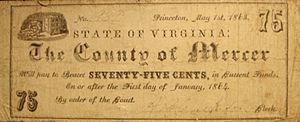

At the start of the Civil War, the Confederacy was just beginning to print its own money. U.S. currency was still used. There were no Confederate coins. Local towns and counties in Virginia, like Lewisburg, began to print their own small paper money (called scrip) for daily transactions. In 1862, a law allowed counties and larger towns to issue scrip for amounts under five dollars. Monroe, Greenbrier, and Mercer counties also issued low-value scrip.

Prisoners and Civilians During the War

Prisoner Exchanges

The Confederate government tried to arrange prisoner exchanges with the U.S. government. Many West Virginia citizens were held in prisons in Wheeling and Camp Chase in Ohio. In October 1861, Virginia's auditor, Jonathan M. Bennett, asked the Confederate Secretary of War to help free or exchange these prisoners. An exchange program started between the two sides, but it ended a few years later.

Judge George W. Thompson was arrested twice for refusing to take an oath of loyalty to the Union-supporting government in Wheeling. He was sent to Camp Chase but was later released in a prisoner exchange. His arrests caused some U.S. officials to question their legality. Joseph Holt, a U.S. Judge-Advocate General, complained that the Wheeling government's many arrests were hurting the prisoner exchange program.

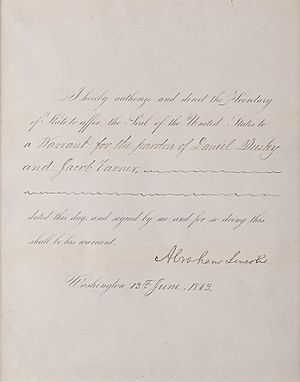

In December 1862, Confederate rangers captured weapons and a U.S. post office in Ripley, Jackson County. They were later captured but treated as civilians and sent to a civilian prison. Governor John Letcher wrote to President Lincoln, saying they were military personnel. Lincoln pardoned the two men, and they were exchanged for Union prisoners.

Confederate authorities also arrested civilians they suspected of disloyalty. Records show 337 men from western Virginia were held in Castle Thunder prison in Richmond. They were arrested for things like voting against secession or having Union soldiers on their property. Civilians often found themselves caught between the two sides. For example, in January 1863, the Union-elected sheriff of Barbour County was arrested by Confederate troops. In response, Governor Pierpont arrested eight Barbour citizens as hostages. One of them died in prison. The sheriff and hostages were eventually released.

Life for Civilians

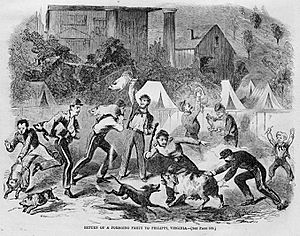

The first major land battle of the war in Philippi, Barbour County, led to widespread looting by Union troops. Even though Union General McClellan promised his troops would respect private property, it was hard to control them. Many claims for destroyed property were made.

Union General George Crook wrote that he had to "burn out" all of Webster County to deal with guerrillas. In January 1862, his troops destroyed buildings and forage for 16 miles. Prisoners were sometimes killed in the field. General John C. Fremont continued this "hard war" policy.

In March 1862, Confederate President Jefferson Davis declared martial law (military rule) in several counties due to complaints about outlaws. General Henry Heth was in charge of enforcing this, but it didn't last long. Some guerrilla groups, while claiming to support the Confederacy, also robbed civilians regardless of their loyalty.

In November 1862, Union General Robert H. Milroy ordered fines on civilians to pay for rebel raids and horse stealing. He threatened fire and executions. Confederate General John Imboden told Jefferson Davis, and a formal protest was made. General Halleck said Milroy had no authority for these orders, which violated war laws. Over $6,000 had been collected by then, but it was later returned.

Sometimes, civilians were forced to move behind Confederate lines. After a raid in May 1863, families were evicted from their homes in Weston. Others, like Dr. Thomas B. Camden, were sent to Camp Chase prison with their families.

It was hard to know who controlled what areas. In August 1861, General McClellan told his troops to focus on main roads and railroads and ignore the inner areas for a while. Union forces occupied counties along the Ohio border and around the B&O railroad. They also held Charleston and the Kanawha Valley. Confederate forces held parts of southern and eastern West Virginia until the end of the war.

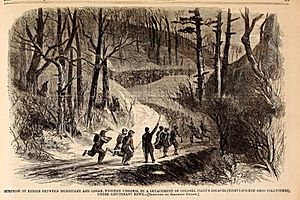

Raids and counter-raids were common from 1862 to 1865, with ongoing guerrilla warfare in much of the state. In 1863, Arthur I. Boreman, who would become the new state's governor, said it wasn't safe for loyal people to go into the interior away from the Ohio River. The ease with which a Confederate raid happened in 1863 frustrated Union generals. In June 1864, Governor Boreman asked General David Hunter to send forces to the southwestern counties, which were "infested with large bodies of guerrillas."

After a Union general and his men were captured in February 1864, an Ohio newspaper wrote that West Virginia might not be as loyal as some thought. It said the state was "just as well stocked with rebels both armed and unarmed as any other portion of the South."

At the end of the war, over 5,000 Confederate soldiers were released in Charleston. Many West Virginians were also released at Appomattox when the main Confederate army surrendered. West Virginians received the same release conditions as soldiers from the 11 Confederate states.

Troubles continued in West Virginia even after the war ended. Some guerrillas kept fighting. Union soldiers were called in to deal with public disturbances until 1868 and finally left the state in 1869.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |