Equites facts for kids

The equites (say: EK-wi-teez) were an important group of people in ancient Rome. Their name means "horsemen" or "cavalrymen" because they were originally the soldiers who rode horses in the Roman army. They were a social class, ranking just below the very powerful senators. If you were a member of this group, you were called an eques (say: EK-wes).

Contents

Who Were the Equites?

The equites were a special group of wealthy Roman citizens. At first, only the richest families, called patricians, could be cavalry soldiers. But over time, more wealthy citizens, even those not from patrician families, joined the cavalry.

Around 400 BC, Rome needed more cavalry, so they started letting other rich citizens join. By the time of the Second Punic War (218–202 BC), many wealthy citizens were required to serve as cavalrymen. Later, equites became more like senior officers in the army, rather than just regular cavalry soldiers.

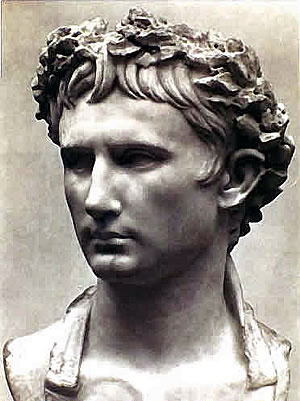

To be an eques, you had to own a certain amount of property. This amount changed over time. For example, Emperor Augustus (who ruled from 30 BC to 14 AD) doubled the required wealth to 100,000 denarii. This was a lot of money, about the same as 450 soldiers' yearly pay!

Under Augustus, the senators became a separate, even higher class. They needed even more wealth (250,000 denarii). Both senators and equites were a very small but powerful group in Rome. They held most of the important jobs in government and the military.

Over the centuries, the power of the equites changed. By the 3rd century AD, many top military jobs went to equites who had earned their rank through brave service, often starting as regular soldiers. By the 4th century, the title of eques became less special because too many people were given the rank.

Early Days of the Equites

Roman stories say that the first king of Rome, Romulus, started the Order of Knights around 753 BC. He supposedly created a group of 300 horsemen called the Celeres to be his personal guards. Later, King Lucius Tarquinius Priscus might have doubled this group to 600 horsemen.

In the early days, the state would give equites money to buy a horse and feed it. This was called an equus publicus (public horse).

The Republic Era

When Rome became a republic (around 509 BC), the army still used 600 cavalrymen. Later, around 400 BC, more cavalry units were created. At this time, some citizens who were wealthy enough but didn't have public horses volunteered to pay for their own horses. This led to soldiers getting paid for cavalry service, just like infantry soldiers.

It's believed that these new cavalry units were open to non-patricians. So, not all equites were patricians anymore. The number of patrician families slowly decreased, while the number of equites grew. However, patricians still had a lot of political power and prestige.

How They Voted

The Roman Republic had a system where political power was mostly held by the richest people. The most important assembly for voting was the comitia centuriata. In this assembly, citizens were divided into groups called centuriae for voting.

The equites (including patricians) had 18 votes, and the first class of commoners had 80 votes. This meant that the wealthiest people had enough votes (98 out of 193 total) to control who was elected to important government jobs like consuls. This system made sure that rich people always held power.

| Class | Wealth Needed (in drachmae or denarii) |

Number of Votes | Military Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rich Citizens | |||

| Patricii (Patricians) | (Born into it) | 6 | Officers and cavalry |

| Equites (Knights) | (Born into it or over 25,000) | 12 | Officers and cavalry |

| Common Citizens | |||

| First Class | 10,000 – 25,000 | 80 | Cavalry |

| Second Class | 7,500 – 10,000 | 20 | Infantry |

| Third Class | 5,000 – 7,500 | 20 | Infantry |

| Fourth Class | 2,500 – 5,000 | 20 | Infantry |

| Fifth Class | 400 – 2,500 | 30 | Light infantry |

| Proletarii (Poorest) | Under 400 | 1 | Sailors |

Military Leaders

During the middle of the Republic (338 – 88 BC), equites were the only ones who could be senior officers in the army. They were the six tribuni militum (military tribunes) in each legion, who took turns commanding the legion. They also commanded the allied cavalry units.

At first, equites made up all the cavalry. But as their numbers became too small, many young men from the first class of commoners volunteered for cavalry service. After the Second Punic War, equites mostly became officers, and the commoners filled the ranks of the cavalry.

Heroic Spirit

Equites were known for their bravery and desire for glory in battle. They wanted to show their worth and bring honor to their families. A big goal for them was to get spolia opima, which were the armor and weapons taken from an enemy leader they had killed in single combat. This was a very rare and high honor.

One famous story is about Titus Manlius Torquatus in 340 BC. He was a cavalry officer who fought and killed an enemy commander in a duel, even though his father, who was a consul, had ordered no one to engage the enemy. Manlius won, but his father had him executed for disobeying orders. This led to the saying "Orders of Manlius" (Manliana imperia), meaning orders that must never be ignored.

Business Life

In 218 BC, a law called the lex Claudia stopped senators and their sons from owning large trading ships. This was because it was thought that big business was not fitting for their high status. So, senators mostly invested their money in land.

But equites were free to invest their wealth in many businesses, like mining, industry, and especially tax farming. By 100 BC, equites owned almost all the tax-farming companies, called publicani.

Tax farming meant that private companies would pay the government an upfront amount for the taxes of a province. Then, they would collect the taxes themselves, keeping any extra money as profit. This often led to publicani charging too much and being unfair to the people in the provinces. This system caused problems and was eventually stopped by Emperor Augustus. After that, equites became more involved in banking, like lending and exchanging money.

Special Privileges

Equites had special clothes and titles. They wore a tunica angusticlavia (a tunic with a narrow purple stripe) under their toga. They also had the right to wear a gold ring (an anulus aureus) on their left hand. From 67 BC, they got special seats at games and public events, just behind the senators.

Equites in the Roman Empire

Under Emperor Augustus, the equites were organized in a more military way. They had their own governing body and even paraded every five years. Augustus also allowed any Roman citizen who met the wealth requirement to use the title eques and wear the special tunic and gold ring, even if they weren't officially part of the ordo equester (the equestrian order).

Only those given a public horse by the emperor (or who inherited the status) were officially part of the order. These equites were the ones who could hold important public jobs.

Public Careers

Equites who were part of the order had a typical career path, combining military and government jobs. After some time in local government, they usually served as military officers for about 10 years.

They commanded the army's auxiliary regiments (non-Roman citizen soldiers) and were senior staff officers in the legions. Their usual military path was to command an auxiliary infantry unit, then be a military tribune in a legion, and finally command an auxiliary cavalry unit.

While senators held the very top jobs, equites were given many important administrative and military roles by Augustus. For example, the governor of Egypt, which was a very important province for Rome's grain supply, was always an eques. They also governed smaller provinces and managed the empire's finances.

Equites also commanded the Praetorian Guard (the emperor's personal bodyguards) and the main imperial fleets. They also led Rome's fire brigade and police force.

These jobs came with very high salaries. For example, a governor of Egypt could earn 75,000 denarii a year! This was much more than a regular soldier earned in their entire 25-year service.

Relationship with Emperors

Some historians believe that emperors trusted equites more than senators. This was because senators, especially those commanding legions in provinces, could become powerful enough to try and overthrow the emperor. Equites were seen as less of a threat. For example, the important province of Egypt was always led by an eques, not a senator, to prevent anyone from gaining too much power over Rome's food supply.

However, equites were not always more loyal or less corrupt. Emperors were careful with powerful equites too. For instance, the command of the Praetorian Guard was usually split between two equites to prevent one person from becoming too powerful.

Powerful Elite

Even though equites outnumbered senators, together they formed a tiny, very rich elite. They controlled most of the political, military, and economic power in the Roman Empire. This small group helped bring a lot of stability to the empire for over 200 years.

Ranks within the Equites

Over time, the equites in imperial service were organized into different ranks based on their pay. There were four main pay grades, with salaries ranging from 60,000 to 300,000 sesterces per year.

Later, three main classes appeared: Viri Egregii (Select Men), Viri Perfectissimi (Best of Men), and Viri Eminentissimi (Most Eminent of Men). The Viri Eminentissimi were usually the commanders of the Praetorian Guard, the highest-ranking equites. The Viri Perfectissimi were heads of major government departments and important prefectures. The Viri Egregii included all other equites serving the emperors.

Equites in the Later Empire

In the 3rd century AD, military equites started taking over the top positions in the army and government. Many of these were career soldiers from the provinces, especially from the Danube region. They were very professional and emperors relied on them heavily.

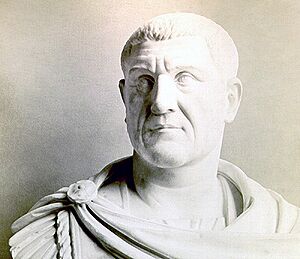

Emperor Diocletian (who ruled from 284–305 AD), who was himself an eques officer, removed hereditary senators from most administrative and military jobs. This meant the old Italian noble families lost much of their power.

By the 4th century, the number of equites grew hugely. Many public jobs were filled by equites, and even local councilors could get the rank. This made the title less prestigious. By 400 AD, being an eques just meant you held a mid-level government job.

A new noble order, the comites (companions of the emperor), was created by Constantine the Great. This group included top military and administrative officers. But like the equites, this title also became less special over time due to too many grants.

By the late 4th century, the senatorial class in Rome and Constantinople became the closest thing to the powerful equites of earlier times. They were still very wealthy landowners, but they had lost almost all their political and military power.

See also

- Publican

- Hippeus

- Medjay

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |