Fuero facts for kids

A Fuero (pronounced FWEH-roh) is a special Spanish word for a set of laws or rules. It comes from the Latin word forum, which was an open space used for markets, courts, and meetings in ancient Rome.

The word fuero can mean different things. It often refers to a collection of laws for a specific town or region. It could also mean special rules for a certain group of people, like the church or the military. Think of it like a special rulebook just for them.

In the 20th century, the leader Francisco Franco used the term fueros for some of his main laws. This made it sound like these laws were old, important orders from a ruler, not something people could debate or change.

Contents

What are Fueros?

Fueros began in the Middle Ages. A powerful lord or king might grant or agree to these special rules for certain groups or communities. This often included the Catholic Church, the military, or specific regions that were part of a kingdom but had their own traditions.

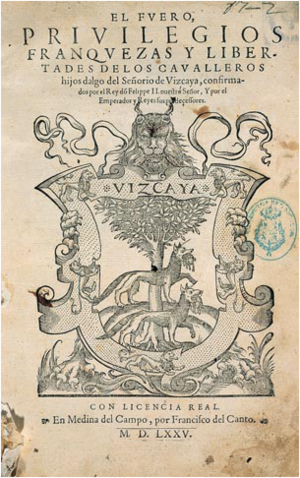

The idea of fueros is still debated today. Some people believe fueros were like a constitution, giving or recognizing rights. For example, the US President John Adams saw the fueros of Biscay (a Basque region) as an early example of a constitution. He thought they showed how people could have special rights.

Others believe fueros were simply special privileges given by a king. In reality, these special rules often came about because of power struggles. Kings might have agreed to them to get people to accept their rule. Or they might have granted them to reward loyal subjects. Sometimes, a king just recognized old traditions that a town or region already had.

In medieval Castile, kings could give special rights to certain groups. For instance, the Roman Catholic Church had many privileges. Clergy did not pay taxes to the state. They also had their own courts, so churchmen were tried by church laws, not civil laws. Another example was the Mesta, a group of wealthy sheep herders. They got huge grazing rights in Andalusia after it was taken back from the Muslims. Some historians believe these special rights slowed down economic growth in southern Spain.

Fueros for Towns and Cities

During the Reconquista (when Christian kingdoms took back land from Muslim rule), feudal lords gave fueros to some towns and cities. This was done to encourage people to settle in new areas or along trade routes. These laws covered how the towns were governed. They also included rules about crime, legal processes, and private matters. Often, a fuero from one town would be copied and slightly changed for another town.

Examples of Early Fueros

|

Year |

Given by |

Given to |

Basque and Pyrenean Fueros

The word fueros is often used today to talk about the special historic rules of the Basque regions in Spain. In France, a similar term is fors, used for the northern Pyrenees regions.

The Basque people and others in the Pyrenees mountains had their own rules for a long time. These rules were different from Roman or Gothic laws. They came from local traditions and were often passed down by word of mouth. Because of this oral tradition, Basque-speaking areas kept their unique laws longer. For example, the laws of Navarre developed differently from nearby kingdoms.

There are old sayings like "in Navarre, there were laws before kings." This means that the laws were so important that kings had to follow them. This sometimes caused problems between the king and the kingdom, especially if the kings were not from the area.

Fueros in the Middle Ages

In 1234, Theobald I, the first foreign king of Navarre, did not know the local laws. He asked a group to write them down. This was the first written fuero for Navarre. French kings ruling Navarre sometimes caused disagreements. This led to conflicts in the 13th century. The Basques' loyalty to the king depended on him respecting their old customs and oral laws.

Fueros and the Kings

When Ferdinand II of Aragon conquered Navarre between 1512 and 1528, he promised to keep Navarre's special laws (fueros). This helped him gain their loyalty. So, Navarre continued to operate under its historic laws. However, in France, King Louis XIII did not respect his father's wish to keep Navarre separate from France. Navarre's special laws and institutions were weakened in 1620–1624. Many important powers were moved to the French Crown.

For centuries, many Basques were born into a special noble status called hidalgo. This meant they had certain privileges. For example, people from Biscay were generally not supposed to be tortured or forced to serve in the Spanish army, unless it was for their own land's defense. Other Basque regions had similar rules.

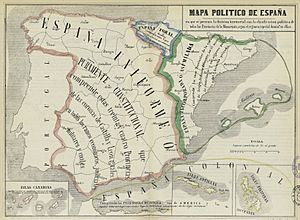

The kings of Castile swore to follow the Basque laws in Álava, Biscay, and Gipuzkoa. These provinces and Navarre kept their own self-governing bodies and parliaments. However, the kings' power often came first. As kings became more absolute, they valued these regional laws less. This led to uprisings and tension between local governments and the Spanish central government.

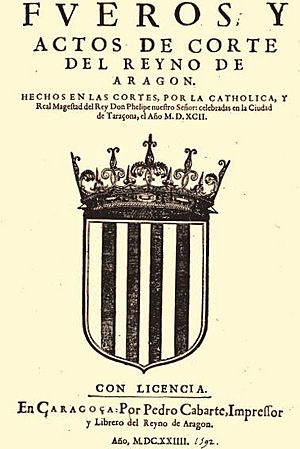

Even though they swore loyalty to the crown, people in Aragon and Catalonia also kept their separate laws. The "King of the Spains" was a title that connected different kingdoms and peoples. The Aragonese fueros caused problems for King Philip II. When his former secretary, Antonio Pérez, escaped a death sentence by fleeing to Aragon, the king could only use the Spanish Inquisition to try him. This was the only court that worked across all kingdoms. Pérez escaped to France, but Philip's army invaded Aragon and punished its leaders.

In 1714, the special laws and self-government of Catalonia and Aragon were violently ended. The Basques managed to keep their special status for a few more years. But the king still tried to centralize power. Before the Napoleonic Wars, relations between the Spanish Crown and Basque governments were very strained.

The End of the Fueros in Spain

The French Revolution in 1789 brought the idea of a single "nation state." This new idea did not allow for regional self-rule. In the French Basque Country, what little self-government remained was ended in 1790. This was followed by the forced movement of thousands of people from border villages.

Some Basques hoped for a separate Basque state under Napoleon in 1808. But the French army's actions and the failure of the self-government plan led the Basques to seek help elsewhere. The Spanish Constitution of 1812 ignored Basque self-government. The Basques accepted it unwillingly, as they were caught up in war.

Over the next two centuries, the level of self-rule for the Basque regions in Spain changed a lot. The call for fueros (meaning regional self-rule) was a main demand of the Carlists in the 19th century. This is why the Basque Country strongly supported the Carlists. The Carlists wanted to bring back an absolute monarchy. They were supported by those who had been protected by the fueros. But the Carlists lost three wars, which led to the loss of more Basque privileges.

The defeat of the Carlists meant that the old noble families lost power. New business owners welcomed the new customs borders. These borders protected new Basque industries from foreign competition and opened up the Spanish market.

Echoes of the Fueros Today

After the First Carlist War, Navarre made a separate agreement in 1841. This gave its provincial government some special administrative and tax rights within Spain. The other Basque regions kept some self-government for another 40 years, but it was finally ended in 1876. The end of the Third Carlist War led to the suppression of their self-government. It was replaced by "Economic Agreements."

Despite these agreements, the Spanish government often tried to ignore them. This caused anger in the Basque regions. It led to an uprising in Navarre in 1893–94. Sabino Arana, who later founded the Basque Nationalist Party, saw this revolt. He was inspired by it. Arana believed in Basque nationalism based on Catholicism and fueros (which he called Lagi-Zaŕa, meaning "Old Law").

A big moment for restoring Basque self-rule came during the Second Spanish Republic in the mid-20th century. An attempt was made to bring back some Basque self-government with the Statute of Estella. However, it failed to pass. Four years later, during a time of war, Basque nationalists supported the Republic. But the defeat of the Republic by Francisco Franco led to the suppression of Basque culture, including banning the public use of the Basque language.

Franco's government saw Biscay and Gipuzkoa as "traitor provinces" and cancelled their fueros. However, Álava and Navarre, which supported Franco, kept some self-rule. They had their own local telephone companies, police forces, road works, and some taxes for local government.

The Spanish Constitution of 1978, after Franco's rule, recognized "historical rights." It tried to find a balance between central control and regional self-rule. It allowed for the creation of "autonomous communities." These communities, like the Basque Country, could have their own governments. The Constitution uses terms like "nationalities" and "historic territories" but does not specifically name Basques or Catalans.

Today, the provincial governments in the Basque regions have been restored. They have gained back important powers. Other powers were transferred to the new government of the Basque Country autonomous community. The Basque provinces still collect taxes in their areas, working with the Basque, Spanish, and European governments.

In Navarre, the act that regulates the government's powers is called the Amejoramiento del Fuero ("Betterment of the Fuero"). Navarre's official name is Comunidad Foral de Navarra, with foral meaning 'chartered' or 'related to fuero'.

Private Law

While fueros are mostly gone from administrative law in Spain (except for the Basque Country and Navarre), some parts of the old laws remain in family law. In places like Galicia and Catalonia, rules about marriage contracts and inheritance are still governed by local laws. This has led to unique ways of dividing land.

These laws are not all the same. For example, in Biscay, different rules apply to inheritance in cities compared to country towns. Modern lawyers try to update these old family laws while keeping their original spirit.

Fueros in Spanish America

During the time of Spanish colonies in America, the Spanish Empire also extended fueros to the clergy. This was called the fuero eclesiástico. It gave special legal privileges to priests. The Spanish Crown tried to limit these privileges. Some historians believe this was a reason why many priests joined the Mexican War of Independence.

In the 18th century, Spain created a standing military in its colonies. Special privileges, called the fuero militar, were given to the military. This affected the colonial legal system. It was the first time that special rights were given to common people.

After Mexico became independent, fueros continued to be recognized. But in the mid-19th century, Mexican liberals gained power. They wanted everyone to be equal before the law. So, they tried to remove the special privileges of the clergy and the military. This led to a civil war, with conservatives fighting for "religion and privileges" (religión y fueros).

List of Fueros

See also

In Spanish: Fuero para niños

In Spanish: Fuero para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |