Giovanni Testori facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giovanni Testori

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 12 May 1923 Novate Milanese, Italy |

| Died | 16 March 1993 (aged 69) Milan, Italy |

| Occupation | Playwright |

| Genre | Drama |

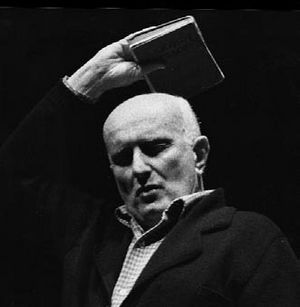

Giovanni Testori (born May 12, 1923, in Novate Milanese, Italy – died March 16, 1993, in Milan, Italy) was a talented Italian writer, journalist, poet, and artist. He was also a critic who wrote about art and books. Testori was a playwright (someone who writes plays), a director for the theater, and even a painter.

Contents

About Giovanni Testori

Early Life and School

Giovanni Testori was born in Novate Milanese, a town near Milan. He was the third of six children. His parents came from a beautiful area called Brianza, which was very important to Testori throughout his life. He often thought about his childhood and family, with whom he was very close.

Giovanni's father, Edoardo, started a textile factory near their home. Giovanni grew up in this house, and it's now where the Giovanni Testori Association is located.

Testori didn't always focus on school at first. But in 1939, he joined a classical high school. He earned his high school certificate in 1942.

While in high school, he developed a strong love for art and theater. Before he was even an adult, he started publishing articles as an art critic. His first essay, written in 1941, was about the artist Giovanni Segantini.

He also wrote for other magazines, focusing on artists of his time. In September 1942, he began studying architecture at the Politecnico di Milano university.

The 1940s: Art and Writing Begin

In 1943, during World War II, Testori and his family had to move to a large house in Sormano. Here, he spent time on another passion: painting. He taught himself how to paint.

During these years, Testori wrote about both modern and older artists. He wrote about artists like Manzù and Henri Matisse. He also wrote about Renaissance artists like Dosso Dossi and Leonardo da Vinci.

Testori also started writing plays in 1942. His first two short plays were La morte (The Death) and Un quadro (A Painting). He also published his first short story in 1943 and his first poem in 1945.

Painting and Reality

During World War II, painting became very important to Testori. He wrote articles about the big debate in Italian art: should art be realistic or abstract? Testori believed art should start from reality. He felt that to truly live and create art, you needed to be fully connected to the real world.

Stopping Painting (for a while)

In 1947, Testori earned a degree in literature from the Università Cattolica di Milano. His final paper looked at how art forms changed in early 20th-century European painting. He believed art in sacred places needed to be updated using modern styles.

Testori's first period as a painter ended around 1948. He painted frescoes (wall paintings) of the Four Evangelists in a church in Milan, which are now lost. He also painted a powerful Crucifixion in 1949, which is now at Casa Testori. After this, he stopped painting for a while. He even destroyed many of his works. He decided to focus almost entirely on writing.

Passion for Theater

In the late 1940s, Testori's love for theater grew. He became friends with Paolo Grassi, who helped create the famous Piccolo Teatro in Milan. From 1947 to 1948, Testori wrote weekly theater reviews for a magazine.

His first play, La Caterina di Dio, was performed in 1948. He wrote another play, Tentazione nel convento, which was not performed until after his death. In 1950, another of his plays, Le lombarde, was staged in Padua.

The 1950s: New Connections and Stories

In 1951, a big art exhibition about Caravaggio was held in Milan. There, Testori met Roberto Longhi, a famous art historian he greatly admired. They became good friends and started working together. Testori began writing for Longhi's new magazine, “Paragone.” His first article for the magazine was about the painter Francesco del Cairo.

In 1954, Testori published his first novel, Il dio di Roserio. This book was about cycling clubs in the towns around Lombardy. Testori often wrote about the lives and struggles of people from these areas. His writing style was unique, mixing dialect words with formal language.

In 1955, Testori helped organize an important art exhibition in Turin. It showed art from Lombardy and Piedmont from the 1600s. He even gave a special nickname, “pestanti” (Plaguesters), to artists from this time because of the plague that affected the region.

Testori also helped with the first big exhibition about the artist Gaudenzio Ferrari in 1956. He wrote about Ferrari's work as both a painter and a sculptor. Testori loved Ferrari's gentle art. But he also admired the more intense work of Antonio d’Enrico, known as Tanzio da Varallo. Testori organized the first exhibition dedicated to Tanzio da Varallo in 1957.

In 1958, Testori published Il ponte della Ghisolfa, the first book in his series I segreti di Milano (The Secrets of Milan). This series told stories about people and their lives in the city's outskirts. These books became very popular around the world. They were translated into French, Spanish, English, and German.

The 1960s: Theater and Poetry

Working with Luchino Visconti

In 1960, Testori's play La Maria Brasca was performed in Milan. That same year, his play L’Arialda was released. It was the first Italian play forbidden for young people. It faced many problems with censorship. The play was directed by the famous Luchino Visconti. When it came to Milan in 1961, a judge ordered the play to be stopped. Testori and his publisher faced legal issues because the text was considered "offensive." However, they were cleared of the charges in 1964.

Meanwhile, in 1960, Visconti released his film Rocco e i suoi fratelli. The movie's story was based on several of Testori's stories from Il Ponte della Ghisolfa.

Testori continued to work on art and theater. In 1967, his play La Monaca di Monza (The Nun of Monza) opened in Rome, again directed by Luchino Visconti.

Poems of Love and Life

In 1965, Testori's father passed away. That year, he published I Trionfi, a very long poem. This was the first part of a series of poems dedicated to Alain Toubas, a close companion in Testori's life. This series continued with L’amore (1968) and Per sempre (1970).

A New Vision for Theater

In 1968, Testori wrote an important article called Il ventre del teatro (The Belly of the Theater). In it, he strongly criticized the Italian theater of his time. He believed that words were the most important part of a play. He felt that theater should use "word-matter" that explores the deepest parts of human existence. He thought monologues (speeches by one person) were especially powerful.

At this time, Testori was working on a play called Erodiade. He was inspired by paintings of Herodias, especially those by Caravaggio. He saw Herodias as a symbol of art that struggles between being cursed and being saved.

Returning to Painting

After stopping painting around 1950, Testori started drawing and painting again by 1968. He created a series of 73 drawings called Heads of John the Baptist. His works were shown in several exhibitions in the 1970s.

The 1970s: New Plays and Public Voice

In 1971 and 1972, Testori curated an exhibition called Il Realismo in Germania (Realism in Germany). This show introduced German Realism and New Objectivity art to the Italian public for the first time.

His writing continued with l’Ambleto (1972), a new version of Shakespeare's Hamlet. This play showed Testori's unique language style, mixing different dialects, Spanish, French, Latin, and new words he invented.

L’Ambleto opened in Milan in 1973. It was the first play at the Salone Pier Lombardo, a new theater Testori helped create. This play was the start of an idea for a "trilogy of traveling players." These plays would be famous stories changed to fit a small group of actors. This series included Macbetto (1974), also based on Shakespeare, and Edipus (1977), based on Sophocles.

Testori also continued his work as an art critic. In 1973, he was involved in a major exhibition about 17th-century Lombard art. He also published books about his favorite realist artists from Northern Italy. He promoted the work of many modern and contemporary artists through exhibitions in galleries.

Saying Goodbye to His Mother

On July 20, 1977, Testori's mother, Lina Paracchi, passed away. She was always very important to him. This sad time led him to reflect on his Christian faith, which he had always held onto, despite life's difficulties.

This period inspired his monologue Conversazione con la morte (Conversation with Death), published in 1978. Testori himself performed this play, touring it to over a hundred places in Italy.

During this time, Testori became close to young people from the Comunione e Liberazione church movement. He found common ground with its founder, Luigi Giussani. They wrote a book together called Il senso della nascita (The Meaning of Birth) in 1980. Testori's connection with young people also led to his play Interrogatorio a Maria (Interrogation of Mary), performed in 1979.

Writing for a Major Newspaper

Giovanni Testori's first article for the important newspaper “Corriere della Sera” appeared on September 10, 1975. It was a review of an art exhibition. This began a long partnership with the newspaper. He wrote about art, books, and important news and cultural topics.

Testori's articles often had a strong impact on public opinion. He wrote about important social and religious issues. He became the art critic and editor of the art page for the newspaper in 1978. Over the next sixteen years, he published more than eight hundred articles. Many of his important articles were collected in his 1982 book, La maestà della vita (The Majesty of Life).

The 1980s: More Plays and Art Focus

A Second Trilogy of Plays

Interrogatorio a Maria was the start of a second group of three plays. It was followed by Factum est (1981) and Post Hamlet (1983).

Factum est was written for Andrea Soffiantini and a new theater company Testori helped create. It was first performed in a church in Florence in 1981. It was a monologue about a fetus (an unborn baby) trying to speak from its mother's womb, begging its parents not to give up on its birth.

Post Hamlet was Testori's third play based on Shakespeare's Hamlet. It was his last book published by Rizzoli. That same year, he moved to Mondadori for his poetry collection Ossa mea (1981-1982).

Honoring Alessandro Manzoni

In 1984, Testori published I Promessi sposi alla prova (The Betrothed to the Test), a play based on Alessandro Manzoni's famous novel. This play was performed in Milan in January 1984. It showed Testori's deep connection to Manzoni, who was a key author in his own education.

Testori also took part in celebrations for Manzoni's 200th birthday in 1985. In 1986, he wrote an essay about the possible inspirations for Manzoni's novel.

New Faces in Art

Testori continued his busy work as an art critic throughout the 1980s. He wrote reviews for newspapers and magazines. He also focused on bringing new, young painters and sculptors to public attention.

He was especially interested in new artists from Austria and Germany. He even created his own group name for some of them, calling them the “Nuovi ordinatori” (New Ordinators).

Art Criticism and Exhibitions

Testori's writings on art during the 1980s included important insights into both old and new art.

In 1981, he curated an exhibition of Graham Sutherland's work. He also helped with a large exhibition about the history of the Ospedale Maggiore hospital in Milan.

That same year, Testori wrote a detailed catalog for the artist Abraham Mintchine. He praised Mintchine's art and believed he would be rediscovered.

In 1983, he curated an exhibition for the artist Guttuso. He also helped with an exhibition about the painter Francesco Cairo.

In 1988, he organized an exhibition of Gustave Courbet's works from private collections. The next year, he showed works by Daniele Crespi. In 1990, Testori wrote the introduction for the complete catalog of Van Gogh's works.

The First "Branciatrilogia"

In the mid-1980s, Testori began a new series of three plays, called the first Branciatrilogia. These plays were written for the actor Franco Branciaroli. The first was Confiteor (1986). This play was inspired by a news story about a man who killed his disabled brother.

In 1988, In exitu was published as a novel. It was also performed with Testori as a co-actor and director. This play used a very unique language, mixing Italian, Latin, and French. It was meant to sound like a person struggling at the very end of their life.

The first Branciatrilogia ended with Verbò. Autosacramental (1989). This play was about the relationship between the poets Verlaine and Rimbaud. Testori and Branciaroli performed it together.

The Second "Branciatrilogia"

In the late 1980s, Testori became ill with cancer. This made him withdraw from public life, but it didn't stop his creativity.

In 1989, he published ...et nihil, a collection of poetry that won an award.

His health worsened in 1990, and he was hospitalized. But he continued to write a lot. He finished a translation of St. Paul's Second Letter to the Corinthians. He also started a second Branciatrilogia of plays. Two of these plays were completed: Sfaust (1990) and sdisOrè (1991). Both were performed by Franco Branciaroli.

The third play in this series, I tre lai. Cleopatràs, Erodiàs, Mater Strangosciàs, was published after his death.

Final Years

After an operation in 1990, Testori spent time recovering at home or in hotels. Even then, he continued to work.

In 1992, his last novel, Gli angeli dello sterminio (The Angels of Extermination), was published. It was set in a chaotic Milan, almost predicting the corruption scandal that hit the city around that time.

His very last play for the theater was Regredior, which was published in 2013 but never performed.

Giovanni Testori passed away in a Milan hospital on March 16, 1993.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Giovanni Testori para niños

In Spanish: Giovanni Testori para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |