History of Hungary facts for kids

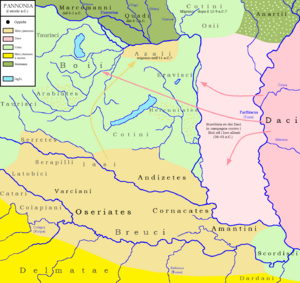

Hungary, located in Central Europe, is mostly made up of a large flat area called the Great Hungarian Plain. Long ago, during the Iron Age, it was a meeting point for different tribes like the Celts, Illyrians, and Germanic peoples.

The name "Pannonian" comes from Pannonia, a Roman Empire province. Only the western part of modern Hungary was part of Pannonia. Roman rule ended around 370–410 AD with the Hunnic invasions. Later, the Ostrogoths and then the Avars controlled the area. The Hungarians, also known as Magyars, moved into the Carpathian Basin between 862 and 895 AD.

The Christian Kingdom of Hungary was founded in 1000 AD by King Stephen I. The Árpád dynasty ruled for three centuries. The kingdom grew, reaching the Adriatic Sea and forming a union with Croatia in 1102. In 1241, the Mongols invaded under Batu Khan, defeating the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi. Many people died, and the kingdom was devastated. The Árpád dynasty ended in 1301. Hungary then faced many wars with the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century, losing much land after the Battle of Mohács in 1526.

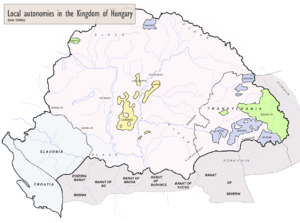

Defense against the Ottomans shifted to the Habsburgs of Austria. The remaining Hungarian kingdom came under Habsburg rule. After the Great Turkish War, all of Hungary became part of the Habsburg monarchy. Following the 1848 uprisings, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 created a joint monarchy, giving Hungary more power. This larger Hungarian territory was known as the Archiregnum Hungaricum.

After World War I, the Habsburg monarchy broke apart. The Treaty of Trianon in 1920 took away about 72% of Hungary's territory, giving it to neighboring countries like Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. A short-lived People's Republic was declared, followed by a restored Kingdom of Hungary, but it was ruled by a regent, Miklós Horthy. Between 1938 and 1941, Hungary regained some lost lands. During World War II, Germany occupied Hungary in 1944, and then the Soviet Union took control until the war ended. After 1945, the Second Hungarian Republic was established, becoming a socialist People's Republic from 1949 until 1989. The Third Republic of Hungary was founded in 1989, and Hungary joined the European Union in 2004.

Contents

Hungary's Early History

Life Before the Romans

Evidence shows that early humans lived in Hungary as far back as 500,000 years ago. Modern humans appeared around 33,000 years ago. Farming began around 6000 BC, and the Bronze Age started around 3000 BC.

The Iron Age began around 800 BC. Different groups like the Scythians and Celts lived in the region. The Pannonians, a type of Illyrian people, were also important.

Celtic tribes started settling in the 4th century BC, taking over much of western Hungary. They even fought successfully against the Scythians. These groups mixed over time. Southern Hungary was controlled by the powerful Celtic Scordisci tribe. The Dacians, another group, became strong in the 1st century BC under their leader Burebista, but his power collapsed after his death.

Roman Rule in Hungary

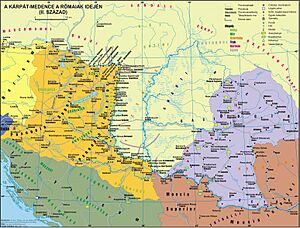

The Roman Empire gradually conquered the area of modern Hungary. Between 35 and 8 BC, Augustus and Tiberius fought the Pannonians. The Romans added these lands to their Illyricum province. Soon, the province of Pannonia was formed. Important Roman cities included Emona (modern Ljubljana) and Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica). The Romans built many roads, making travel on the Danube River easier.

The Dacians to the east, led by Decebalus, bothered the Roman border defenses. Emperor Trajan defeated them in two wars and created the province of Dacia. Latin, Greek, and Asian settlers moved in, and cities like Ulpia Traiana and Napoca (Cluj-Napoca) were founded. They mined a lot of gold and silver in Transylvania. Later, the Germanic Goths forced Emperor Aurelian to leave the province.

After a long period of peace, Pannonia faced frequent wars with Germanic and Sarmatian peoples from the north and east. The Vandals and Goths marched through, causing much destruction. After the Roman Empire split, Pannonia remained with the Western Roman Empire. As Romans left, Hunnic groups appeared near the Danube. Under King Rugila, the Huns settled the Great Hungarian Plain. In 433, the western part of Pannonia also came under Attila's control.

The Migration Period

In 453, King Attila died, and his empire quickly fell apart. The Huns moved back to Eastern Europe after Attila's son, Ellac, was defeated by Germanic tribes. The Ostrogoths and Gepids then set up their kingdoms in the Carpathian Basin. Their wars left the region in ruins.

From the early 6th century, the Lombards slowly took over parts of the region. After a series of wars, the Pannonian Avars invaded, led by Khagan Bayan I. The Lombards left for Italy in 568, and the Avars took control of the entire basin.

The Avars ruled for almost 250 years. Their khagan controlled a large area from Vienna to the Don River. They often fought against the Byzantines, Germans, and Italians. The Avars mixed with Slavic and Germanic peoples. They also brought other groups with them and played a role in Slavic migrations to the Balkans.

In the 7th century, the Avar society faced problems. After failing to capture Constantinople in 626, many groups rebelled against them. The Frankish Empire became their main rival.

After Charlemagne became king of Bavaria in 788, the Franks and Avars shared a long border. Conflicts were common. In 791, they went to war. The Franks won a quick victory, but the Avars used a "scorched-earth" strategy, avoiding battles and destroying food supplies. This caused many losses for the Frankish army. Four years later, a civil war broke out among the Avars. Charlemagne took over western Hungary, annexing it as the Avar March. Beyond the Danube, the Bulgars defeated the new Avar khagan in 804. The Avar Khaganate almost disappeared.

Even though their power was greatly reduced, the Avars continued to live in the Carpathian Basin. However, the number of Slavs, who came mainly from the south, grew rapidly. The expanding Kingdom of the East Franks prevented most Slavic groups from developing strong states. Only the Principality of Moravia managed to grow into modern-day Western Slovakia. The Bulgarians were not strong enough to control Transylvania effectively.

Medieval Hungary

Conquest and Early Kingdom (895–1000)

The Hungarians, also called Magyars, moved into the Carpathian Basin in the late 9th century. They were first mentioned living there in 862. The actual conquest began in 894, when they started fighting the Bulgarians and Moravians. The Hungarians took over the basin quickly. They defeated the First Bulgarian Tsardom and broke up the Principality of Moravia. By 900, they had firmly established their state. The invasion was peaceful for the local people, as leaders like Árpád and Kurszán did not leave mass graves.

The Hungarians' military strength allowed them to launch successful campaigns as far as modern Spain. However, a defeat at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 ended their raids on western lands. Raids continued against the Byzantine Empire until 970.

Duke Géza (c. 940–997) of the Árpád dynasty ruled part of the Hungarian territory. He wanted to bring Hungary into Christian Western Europe. Géza chose his son Vajk (later King Stephen I) as his successor, which was unusual for the time. Normally, the oldest surviving family member would take the throne.

After Géza's death in 997, Prince Koppány, the oldest family member, rebelled. He wanted to keep the old traditions and pagan beliefs. Stephen defeated Koppány and had him executed.

The name "Hungary" comes from the Greek word Oὔγγροι for the Magyars. The letter 'H' was added later in Medieval Latin. One idea is that the name comes from the Old Turkic name for the On-Oğur ("ten tribes") group. During the Middle Ages, Byzantine sources also called the Hungarian state Tourkia (Turkey).

The Kingdom Under the Árpád Dynasty (1000–1301)

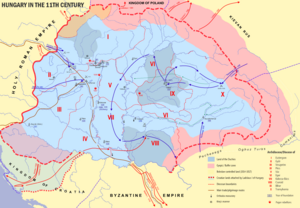

Hungary became an "Apostolic Kingdom" under Saint Stephen I. He was crowned with the Holy Crown of Hungary around 1000 AD. Pope Sylvester II gave him special rights over churches. By 1006, Stephen had secured his power by defeating rivals who wanted to follow old pagan ways or ally with the Byzantine Empire. Stephen set up a system of ten bishoprics and two archbishoprics. He also ordered the building of monasteries, churches, and cathedrals.

The Hungarian language is part of the Uralic language family. It was first written with a runic-like script. Under Stephen, the country switched to the Latin alphabet, and Latin was the official language until 1844. Stephen followed the Frankish way of governing. The land was divided into counties (megyék), each led by a royal official called an ispán. The ispán represented the king, managed people, and collected taxes. Each ispán had an armed force at their fortified castle.

After the Great Schism in 1054, which split Western Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Hungary saw itself as a protector of Western civilization. Pope Pius II later called Hungary "the shield of Christianity."

The Árpád dynasty ruled through the 12th and 13th centuries. King Béla III (1172–1196) was the richest and most powerful king of this dynasty. His annual income was worth about 23,000 kg of pure silver. This was more than the French king's income and double that of the English Crown. In 1195, Béla expanded the kingdom south and west to Bosnia and Dalmatia.

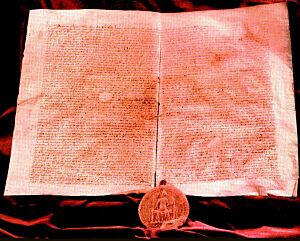

The early 13th century saw the reign of King Andrew II (1205–1235). In 1211, he gave land in Transylvania to the Teutonic Knights, but he expelled them in 1225. Andrew led the largest royal army in the Crusades (20,000 knights) to the Holy Land in 1217. In 1224, he issued the Diploma Andreanum, which protected the special rights of the Transylvanian Saxons.

Andrew II was forced to accept the Golden Bull of 1222. This was like England's Magna Carta. Every Hungarian king had to swear to it. The Golden Bull limited the king's power. It protected the rights of smaller nobles against the crown and powerful lords. It also defended the rights of the whole nation by restricting the king's power and making it legal to refuse unlawful commands. The smaller nobles began to present their complaints to the king, which led to the creation of the Parliament, or Diet. Hungary became the first country where a parliament had power over the king. The most important idea was that power belonged to the noble nation, represented by the Holy Crown.

Mongol Invasions

In 1241–1242, the Mongol invasion caused huge damage to Hungary. The Hungarian army was badly defeated at the Battle of Mohi. King Béla IV fled the country. Before the Mongols left, 20-50% of the population died. In the plains, 50-80% of settlements were destroyed. Only castles and strong cities survived, as the Mongols did not have time for long sieges.

After the Mongols left, King Béla invited settlers from other parts of Europe, especially Germany, to rebuild the country. About 40,000 Cumans, a nomadic tribe, came to Hungary after being defeated by the Mongols. The Jasz people also came with the Cumans. Cumans made up about 7–8% of Hungary's population in the late 13th century. They were later absorbed into the Hungarian population but kept their identity until 1876.

Because of the Mongol invasions, King Béla ordered hundreds of stone castles and fortifications to be built. These helped defend against a possible second Mongol invasion. The Mongols did return in 1286, but the new castles and military tactics stopped them. The Hungarian army defeated the Mongols near Pest. These castles also proved very useful later in the long fight against the Ottoman Empire. However, building them made the king owe money to the powerful feudal lords, which weakened the royal power.

Late Medieval Period (1301–1526)

After the Árpád Dynasty

After a period of disorder (1301–1308), Charles I, the first Angevin king of Hungary, successfully brought back royal power. He defeated powerful rivals known as "little kings." Charles I, who was related to the Árpád dynasty through his mother, ruled from 1308 to 1342. His new tax, customs, and money policies worked well.

A main source of the new king's power was the wealth from gold mines in eastern and northern Hungary. These mines produced about 1350 kg of gold each year. This was one-third of the world's total production at the time and five times more than any other European country. Charles also made an alliance with Polish King Casimir the Great. Hungary was one of the first European countries where the Renaissance appeared. A printing press was set up in Buda in 1472, one of the earliest outside Germany.

Louis the Great (1342–1382), the second Angevin king, expanded his rule to the Adriatic Sea. He even occupied the Kingdom of Naples several times. In 1351, a law was added to the Golden Bull of 1222. This law said that nobles' inherited lands could not be taken away and had to stay in their families. Louis also became king of Poland from 1370 to 1382. He was popular in Poland because he fought against the Tatars and pagan Lithuanians. In two wars against Venice, he took over Dalmatia and other territories on the Adriatic Sea. Louis also had a strong influence in Italy.

Some Balkan states like Wallachia and Serbia became his vassals. Louis led successful campaigns against the Ottoman Turks in 1366 and 1377. He also founded a university in Pécs in 1367.

King Louis died without a son. After years of civil war, Sigismund (1387–1437), a prince from the Luxembourg family, became king by marrying Louis the Great's daughter, Mary. Mary was even crowned a "king" in 1382. Sigismund had to give up some royal properties to gain support from the lords. For a while, a council of barons ruled the country, and the king was even imprisoned briefly. It took decades to bring back central control. After Mary's death, Sigismund ruled alone.

In 1404, Sigismund introduced the Placetum Regnum. This rule meant that papal messages could not be announced in Hungary without the king's permission. Sigismund called the Council of Constance (1414–1418) to end the Western Schism in the Catholic Church. During his long reign, the royal castle of Buda became one of the largest Gothic palaces of the late Middle Ages.

After Sigismund died in 1437, his son-in-law, Albert II of Germany, became King of Hungary. In 1437, there was a peasant revolt in Transylvania, influenced by Hussite ideas. The first Hungarian Bible translation was finished in 1439, just before Albert's death.

John Hunyadi, from a small noble family in Transylvania, became one of the country's most powerful lords. He was a great military leader. In 1446, the parliament elected him governor, and then regent (1453–1456). He was a successful crusader against the Ottoman Turks. One of his greatest victories was the Siege of Belgrade in 1456. Hunyadi defended the city against the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. During the siege, Pope Callixtus III ordered church bells to ring at noon every day for prayers. In many countries, the news of victory arrived first, so the ringing became a celebration of the victory. Catholic churches still ring the noon bell today.

Matthias Corvinus

The last strong Hungarian king was Matthias Corvinus (1458–1490), John Hunyadi's son. He was the first noble without royal family ties to become king. Matthias was a true Renaissance prince: a successful military leader, a good administrator, a linguist, an astrologer, and a supporter of arts and learning. He often called the Diet (Parliament) and gave more power to the smaller nobles in the counties. However, he ruled Hungary with absolute power through a large government.

Matthias wanted to expand his kingdom to the south and northwest and made changes inside the country. Peasants saw Matthias as a fair ruler because he protected them from greedy lords. Like his father, Matthias wanted to make Hungary the strongest power in the region, strong enough to push back the Ottoman Empire. To do this, he felt he needed to conquer parts of the Holy Roman Empire.

Matthias had a strong mercenary army called the Black Army of Hungary. This was a very large army for its time. It won many victories in the Austrian–Hungarian War, capturing parts of Austria (including Vienna) in 1485, and parts of Bohemia. In 1467, Matthias fought against Moldavia but lost the Battle of Baia. However, in 1479, the Hungarian army destroyed Ottoman and Wallachian troops at the Battle of Breadfield.

Matthias's library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe's largest collection of historical books, philosophy, and science in the 15th century. It was second only to the Vatican Library in Rome. The library was destroyed in 1526 after the Hungarian defeat at Mohács. Matthias died without a legal heir, which caused a serious political crisis in Hungary.

Decline and Division

Events between 1490 and 1526 led to Hungary losing its independence. Besides internal conflicts, the country was greatly threatened by the growing Ottoman Empire. By the early 16th century, the Ottoman Empire, just south of Hungary, was the second most populated state in the world. This allowed them to raise very large armies. However, Hungarian leaders at the time did not fully realize how serious this threat was.

Instead of preparing for defense, Hungarian lords focused on protecting their own privileges from a strong king. After Matthias Corvinus died without children, the lords chose Vladislaus II of Bohemia as king because he was known to be weak. He was even called King Dobzse ("Good" or "OK") because he would agree to everything. During his reign (1490–1516), the central government faced big money problems. The lords also dismantled the strong government systems Matthias had built. The country's defenses weakened as border guards and castle soldiers were not paid, and fortresses fell apart. Hungary's role in international politics became weak, its political stability was shaken, and social progress stopped.

In 1514, the weak King Vladislaus faced a major peasant rebellion led by György Dózsa. Hungarian nobles crushed it brutally. This disorder made it easier for the Ottomans to take Hungarian land. In 1521, the strongest Hungarian fortress in the south, Nándorfehérvár (modern Belgrade), fell to the Turks. In 1526, the Hungarian army was crushed at the Battle of Mohács. The young King Louis II died in the battle. The early spread of Protestantism further worsened internal unity in the country.

Early Modern Period

Wars with the Ottomans

After the Ottomans' big victory at the Battle of Mohács, they conquered large parts of Hungary and continued to expand until 1556. This time was full of political chaos. The Hungarian nobles were divided and elected two kings at the same time: Szapolyai and Ferdinand of Habsburg from Austria. Fights between these rival kings further weakened the country. When the Turks conquered Buda in 1541, Hungary was split into three parts.

The northwestern part of old Hungary (today's Slovakia, western Hungary, and parts of Croatia) remained under Habsburg rule as "Royal Hungary." The Habsburg emperors were also crowned kings of Hungary. The Turks could not conquer these northern and western parts.

The eastern part of the kingdom (Transylvania) became an independent principality at first. But it gradually came under Turkish rule as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The central area (most of present-day Hungary), including the capital Buda, became a province of the Ottoman Empire. Much of the land was destroyed by constant warfare. Most small Hungarian settlements disappeared. People in the Ottoman provinces could only survive in larger towns that were directly protected by the sultan. The Turks did not care about the Christian religions of their Hungarian subjects.

Because of this, most Hungarians living under Ottoman rule became Protestant (mostly Calvinist). This was because the Habsburgs' efforts to bring back Catholicism could not reach the Ottoman lands. During this time, Pozsony (today Bratislava) was the capital of Hungary (1536–1784). Hungarian kings were crowned there, and the Hungarian Parliament met there. Nagyszombat (modern Trnava) became the religious center. Most soldiers in Ottoman fortresses in Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs, not ethnic Turks.

In 1558, the Transylvanian Diet (assembly) of Turda declared that Catholic and Lutheran religions could be practiced freely, but Calvinism was forbidden. In 1568, this freedom was extended, saying, "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expulsion for his religion." Four religions were accepted, while Orthodox Christianity was "tolerated" (though building stone Orthodox churches was forbidden). When Hungary entered the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), Royal (Habsburg) Hungary joined the Catholic side, and Transylvania joined the Protestant side.

In 1686, a new European campaign began to retake the Hungarian capital. The army of the Holy League was very large, with over 74,000 soldiers from many European countries. They reconquered Buda in the second Battle of Buda. The second Battle of Mohács (1687) was a huge defeat for the Turks. In the next few years, all former Hungarian lands, except areas near Timișoara, were taken back from the Turks. By the end of the 17th century, Transylvania also became part of Hungary again. The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 officially recognized these changes. By 1718, the entire kingdom of Hungary was free from Ottoman rule.

The constant wars between Hungarians and Ottoman Turks stopped population growth. Many medieval settlements and their city dwellers were destroyed. The 150 years of Turkish wars greatly changed Hungary's ethnic makeup. Due to population losses, including forced removals and massacres, the number of ethnic Hungarians was much smaller by the end of the Turkish period.

Uprisings Against the Habsburgs

There were several uprisings against Habsburg rule between 1604 and 1711. These rebellions were against Austrian control and limits on non-Catholic Christian religions. Most of them happened in Royal Hungary but were often organized from Transylvania. The last uprising was led by Francis II Rákóczi, who became the "Ruling Prince" of Hungary after the Habsburgs were declared dethroned in 1707.

Despite some successes by Rákóczi's Kuruc army, the rebels lost the important Battle of Trenčín in 1708. When the Austrians defeated the Kuruc uprising in 1711, Rákóczi was in Poland. He later fled to France and then to Turkey, where he died in 1735. To prevent future armed resistance, the Austrians destroyed most of the castles on the border between the recovered territories and Royal Hungary.

Modern History

Period of Reforms (1825–1848)

Hungarian nationalism grew among thinkers influenced by the Age of Enlightenment and Romanticism. It quickly became strong, leading to the revolution of 1848–1849. There was a special focus on the Magyar language, which replaced Latin as the language of the state and schools. In the 1820s, Emperor Francis I had to call the Hungarian Diet, which started a Reform Period. However, progress was slow because nobles held onto their privileges, like not paying taxes and having exclusive voting rights. So, many achievements were symbolic, like the progress of the Magyar language.

Count István Széchenyi, a leading statesman, saw the urgent need for modernization. Other Hungarian political leaders agreed with him. The Hungarian Parliament met again in 1825 to deal with money problems. A liberal party emerged, focusing on peasants and workers' needs. Lajos Kossuth became the leader of the lower nobility in Parliament. Habsburg rulers wanted Hungary to remain an agricultural, traditional country and tried to stop its industrialization. Despite Habsburg opposition to important liberal laws about civil rights and economic reforms, the nation began to modernize. Many reformers, like Lajos Kossuth, were imprisoned.

Revolution and War of Independence

On March 15, 1848, large protests in Pest and Buda allowed Hungarian reformers to push for their "Twelve Demands." The Hungarian Diet used the Revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas to pass the April Laws, which included many civil rights reforms. Facing revolutions at home and in Hungary, Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I at first accepted Hungarian demands. After the Austrian uprising was put down, a new emperor, Franz Joseph, replaced Ferdinand. Joseph rejected all reforms and began to prepare for war against Hungary. A year later, in April 1849, an independent Hungarian government was formed.

The new government separated from the Austrian Empire. The Habsburg family was removed from power in Hungary, and the first Republic of Hungary was declared. Lajos Kossuth became governor and president, and Lajos Batthyány was the first prime minister. Joseph and his advisors cleverly used the new nation's ethnic minorities, like Croatian, Serbian, and Romanian peasants, who were loyal to the Habsburgs. They encouraged these groups to rebel against the new Hungarian government. However, most Slovaks, Germans, and Rusyns, as well as many Poles, Austrians, and Italians, supported the Hungarians.

Many non-Hungarian people held high positions in the Hungarian army, like General János Damjanich, an ethnic Serb who became a Hungarian national hero. At first, the Hungarian forces (Honvédség) held their ground. In July 1849, the Hungarian Parliament passed the most advanced ethnic and minority rights laws in the world, but it was too late. To crush the Hungarian revolution, Joseph prepared his troops and got help from Russian Czar Nicholas I. In June, Russian armies invaded Transylvania, while Austrian armies marched on Hungary from the west.

The Russian and Austrian forces overwhelmed the Hungarian army, and General Artúr Görgey surrendered in August 1849. The Austrian marshal Julius Freiherr von Haynau then became governor of Hungary. On October 6, he ordered the execution of 13 Hungarian army leaders and Prime Minister Batthyány. Kossuth escaped into exile. After the war, the country entered a period of "passive resistance." Archduke Albrecht von Habsburg was appointed governor, and this time was known for efforts to make Hungary more German, with the help of Czech officers.

Austria-Hungary (1867–1918)

Vienna realized that political reform was needed to keep the Habsburg Empire together. Major military defeats, like the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866, forced Emperor Joseph to accept changes. To calm Hungarian separatists, the emperor made a fair deal with Hungary, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. This created the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The two parts were governed separately by two parliaments from two capitals, but they had a common monarch and shared foreign and military policies. Economically, the empire was a customs union. The first prime minister of Hungary after the compromise was Count Gyula Andrássy. The old Hungarian constitution was restored, and Franz Joseph was crowned king of Hungary.

In 1868, Hungarian and Croatian assemblies made the Croatian–Hungarian Agreement. This recognized Croatia as an autonomous region.

Austria-Hungary was the second largest country in Europe after Russia. Its area was about 621,538 square kilometers in 1905. It was also the third most populated country in Europe.

Hungarian nationalists wanted education in the Magyar language. This united Catholics and Protestants who opposed Latin instruction. In the diet of 1832–1836, the conflict between Catholic laypeople and clergy grew. A commission was set up and offered Protestants some limited concessions. The main goal of this religious and educational struggle was to promote the Magyar language and Hungarian nationalism, and to gain more independence from German Austria.

The land-owning nobility controlled the villages and held most political roles. In Parliament, the powerful lords had lifetime memberships in the upper house. But the lower nobility dominated the lower house and parliamentary life after 1830. The tension between the "crown" (the German-speaking Habsburgs in Vienna) and the "country" remained constant. The Compromise of 1867 allowed the Hungarian nobility to run the country, but the emperor kept control over foreign and military policies. After Andrássy served as prime minister, he became foreign minister of Austria-Hungary (1871–1879) and set foreign policies that favored Hungarian interests. Andrássy was a conservative. His foreign policies aimed to expand the empire into southeast Europe, preferably with British and German support, and without upsetting Turkey. He saw Russia as the main enemy because of its own expansion into Slavic areas. He did not trust Slavic nationalist movements, seeing them as a threat to his multi-ethnic empire. Meanwhile, conflicts between powerful lords and lower nobility arose over cheap food imports (1870s), church-state issues (1890s), and a "constitutional crisis" (1900s). The lower nobility gradually lost local power and built their political base more on holding government jobs than on owning land. They relied more on the state and were less likely to challenge it.

Economy

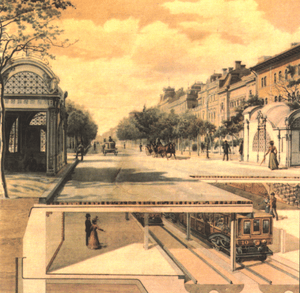

This period saw great economic growth in rural areas. The Hungarian economy, once behind, became quite modern and industrialized by the early 20th century, though farming remained the main part of the economy until 1880. In 1873, the old capital Buda and Óbuda (ancient Buda) officially merged with Pest, creating the new large city of Budapest. Dynamic Pest grew into the country's administrative, political, economic, trade, and cultural center.

Technology sped up industrialization and urbanization. The GDP per person grew about 1.45% per year from 1870 to 1913. This growth was very good compared to other European nations like Britain (1.00%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%). The leading industries were electricity, telecommunications, and transport (especially trains, trams, and ships). Key symbols of industrial progress were the Ganz and Tungsram companies. Many of Hungary's state institutions and modern government systems were set up during this time.

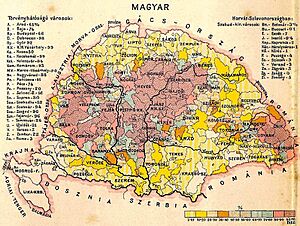

The 1910 census for Hungary (excluding Croatia) showed the population breakdown: Hungarian 54.5%, Romanian 16.1%, Slovak 10.7%, and German 10.4%. The largest religious group was Roman Catholicism (49.3%), followed by Calvinism (14.3%), Greek Orthodoxy (12.8%), Greek Catholicism (11.0%), Lutheranism (7.1%), and Judaism (5.0%).

World War I

After Archduke Franz Ferdinand was killed in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, a series of crises quickly grew. A general war began on July 28 when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Austria-Hungary drafted 9 million soldiers in World War I, with 4 million from Hungary. Austria-Hungary fought with Germany, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire, known as the Central Powers. They occupied Serbia, and Romania declared war. The Central Powers then conquered southern Romania and its capital, Bucharest. In November 1916, Emperor Franz Joseph died. The new monarch, Emperor Charles I, sympathized with those who wanted peace.

In the east, the Central Powers pushed back attacks from the Russian Empire. The Eastern Front of the Allied Powers, who were allied with Russia, completely collapsed. Austria-Hungary withdrew from the defeated countries. On the Italian front, the Austro-Hungarian army could not make much progress against Italy after January 1918. Despite successes on the Eastern Front, Germany faced a stalemate and eventual defeat on the more important Western Front.

By 1918, the economic situation in Austria-Hungary had become very bad. Strikes in factories were organized by leftist and pacifist groups, and army uprisings were common. In Vienna and Budapest, Austrian and Hungarian leftist liberal movements supported the separation of ethnic minorities. Austria-Hungary signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti in Padua on November 3, 1918. In October 1918, the personal union between Austria and Hungary was dissolved.

Between the World Wars (1918–1939)

After a short-lived communist government collapsed, Hungary became a right-wing country between 1919 and 1944. Its governments promoted a "nationalist Christian" policy. They praised heroism, faith, and unity. They disliked the French Revolution and rejected the liberal and socialist ideas of the 19th century. The governments saw Hungary as a defense against communism and its tools: socialism, globalism, and Freemasonry. A small group of aristocrats, civil servants, and army officers ruled, and the head of state, Admiral Horthy, was greatly admired.

The Hungarian People's Republic

After World War I, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy fell apart. Former Prime Minister István Tisza was killed in Budapest during the Aster Revolution in October 1918. On October 31, 1918, this revolution brought the leftist liberal Count Mihály Károlyi to power as prime minister. Károlyi had supported the Allied powers from the start of the war. On November 13, 1918, Charles I gave up his powers as king of Hungary, but he did not officially resign, which meant he could potentially return to the throne.

French Allied troops landed in Greece to re-arm Romania and Serbia and help the new country of Czechoslovakia. Despite a general ceasefire, the French army in the Balkans organized new campaigns against Hungary with the help of the Czechoslovak, Romanian, and Serbian governments.

The First Hungarian Republic was declared on November 16, 1918, with Károlyi as president. Károlyi tried to build the republic as an "eastern Switzerland" and convince non-Hungarian minorities (like Slovaks, Romanians, and Ruthenians) to stay loyal by offering them self-rule. However, these efforts came too late. Károlyi, believing in peace, ordered the Hungarian army to disarm completely. This left the republic without defense at a very vulnerable time. The surrounding new states quickly armed themselves and occupied large parts of Hungary with Allied help, even though their borders were not yet agreed upon.

On November 5, 1918, the armed forces of the provisional State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, with French support, attacked southern Hungary. On November 8, the armed forces of the Czechoslovak Republic attacked northern Hungary. The Treaty of Bucharest, signed in May 1918, was canceled by the Romanian government in October 1918. Romania then re-entered the war on the Allied side and advanced into Transylvania.

A movement inspired by Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points declared that Transylvania would unite with Romania. In November, the Romanian National Central Council told the Budapest government that it would take control of 23 Transylvanian counties. The Hungarian government rejected this, saying it did not protect the rights of ethnic Hungarians and Germans.

On December 2, the Romanian army began attacking the eastern (Transylvanian) parts of Hungary. Despite the foreign armies marching in, the Károlyi government made all spontaneous armed groups illegal. It tried to keep the old kingdom's territory intact but refused to rebuild the Hungarian armed forces. These actions failed to stop public unhappiness, especially when the Allied powers started giving parts of Hungary's traditional territories to Romania, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, based on ethnic groups rather than historical borders. French and Serbian forces occupied the southern parts of the former monarchy.

By February 1919, the new pacifist Hungarian government had lost all public support due to its failures at home and in the military. On March 21, 1919, after the Allied military representative demanded more land from Hungary, Károlyi signed all the demands and resigned.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Communist Party of Hungary, led by Béla Kun, joined with the Hungarian Social Democratic Party. They came to power and declared the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Sándor Garbai was the official head of government, but Béla Kun, in charge of foreign affairs, really controlled the Soviet Republic. The communists, called "The Reds," came to power mostly because they had an organized fighting force. They promised that Hungary would defend its territory without forcing people into the army, possibly with help from the Soviet Red Army.

The Hungarian Red Army was a small volunteer army of 53,000 men, mostly armed factory workers from Budapest. At first, Kun's government had some military successes. Under Colonel Aurél Stromfeld, the Hungarian Red Army drove Czechoslovak troops out of the north and planned to march against the Romanian army in the east. At home, the communist government took over industries, businesses, housing, transport, banks, medicine, and all large landholdings.

However, support for the communists in Budapest was short-lived, and they were never popular in towns and the countryside. After a failed coup attempt, the government started the "Red Terror," killing hundreds of people, mostly scientists and intellectuals. The Soviet Red Army never helped the Hungarian republic. Despite military successes against the Czechoslovakian army, the communist leaders gave back all the recaptured lands. This discouraged the volunteer army, and the Hungarian Red Army was dissolved. Facing anger at home and an advancing Romanian army in the Hungarian–Romanian War of 1919, Béla Kun and most of his friends fled to Austria. Budapest was occupied on August 6. Kun and his followers took many art treasures and the national bank's gold. These events, especially the final military defeat, led to a strong dislike among the public for the Soviet Union (which did not offer military help) and Hungarian Jews.

The Counterrevolution

The new fighting force in Hungary was the Conservative Royalist "Whites." These counter-revolutionaries, who had been organizing in Vienna and set up a counter-government in Szeged, took power. They were led by István Bethlen, a Transylvanian aristocrat, and Miklós Horthy, the former commander of the Austro-Hungarian navy. The conservatives saw the Károlyi government and the communists as traitors.

Without a strong national police or regular army, a "White Terror" began in western Hungary. This was carried out by semi-regular and semi-military groups and spread across the country. Many communists and other leftists were executed without trial. Radical Whites attacked Jews, blaming them for Hungary's territorial losses. The most famous White commander was Pál Prónay. The retreating Romanian army looted the country, taking livestock, machinery, and farm products to Romania in hundreds of freight cars.

On November 16, 1919, with permission from Romanian forces, the army of right-wing former admiral Miklós Horthy marched into Budapest. His government slowly brought back order and stopped the terror. However, thousands of supporters of the Károlyi and Kun governments were imprisoned. Radical political movements were suppressed. In March 1920, the parliament restored the Hungarian monarchy as a regency but delayed choosing a king until civil disorder ended. Instead, Horthy was elected regent. He was given power to appoint the prime minister, veto laws, call or dissolve parliament, and command the armed forces.

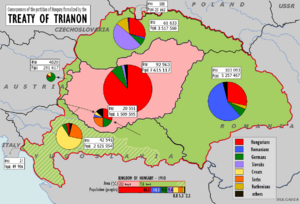

The Treaty of Trianon

Hungary's agreement to the Treaty of Trianon on June 4, 1920, confirmed the decision of the victorious Allied powers to redraw the country's borders. The treaty forced Hungary to give up more than two-thirds of its pre-war territories. The goal was to allow minority populations of the former Austria-Hungary to live in states dominated by their own ethnic group. However, many Hungarians still lived in these new territories. As a result, almost one-third of the 10 million ethnic Hungarians found themselves living outside their smaller homeland. They became unhappy minorities in hostile countries.

New international borders separated Hungary's industries from its old sources of raw materials and its former markets for farm and industrial products. Hungary lost 84% of its timber, 43% of its farmland, and 83% of its iron ore. Although post-Trianon Hungary kept 90% of the engineering and printing industry, it only kept 11% of timber and 16% of iron. Also, 61% of farmland, 74% of public roads, 65% of canals, 62% of railroads, 64% of hard surface roads, 83% of pig iron output, 55% of industrial plants, 100% of gold, silver, copper, mercury, and salt mines, and most importantly, 67% of credit and banking institutions of the former Kingdom of Hungary were now in neighboring countries.

"Irredentism"—the demand for the return of lost territories—became a main theme in Hungarian politics.

The Regency

Horthy appointed Count Pál Teleki as prime minister in July 1920. His government passed a law that limited the admission of "politically insecure elements" (often Jews) to universities. It also began to fulfill a promise of major land reform by dividing about 3,850 square kilometers from large estates into small holdings to calm rural unrest. However, Teleki's government resigned after Charles I of Austria, the former emperor and king of Hungary, tried unsuccessfully to retake Hungary's throne in March 1921. This attempt divided conservative politicians who wanted a Habsburg restoration and nationalist right-wing radicals who supported choosing a native Hungarian king. Count István Bethlen, a right-wing member of parliament, used this division to form a new Party of Unity under his leadership. Horthy then appointed Bethlen prime minister. Charles died soon after his second failed attempt to reclaim the throne in October 1921, and Hungary remained a kingdom without a king.

Prime Minister Bethlen controlled Hungarian politics between 1921 and 1931. He built a political system by changing election laws, giving jobs in the growing government to his supporters, and manipulating elections in rural areas. Bethlen brought order back to the country by giving money and government jobs to radical counter-revolutionaries in exchange for them stopping their terror against Jews and leftists.

In 1921, Bethlen made a deal with the Social Democrats and trade unions (called the Bethlen-Peyer Pact). He legalized their activities and freed political prisoners. In return, they promised not to spread anti-Hungarian ideas, call political strikes, or try to organize peasants. Bethlen brought Hungary into the League of Nations in 1922 and ended its international isolation by signing a friendship treaty with Italy in 1927. Overall, Bethlen tried to strengthen the economy and build relations with stronger nations. The demand for the return of lost territories, or irredentism, became the top political goal in Hungary. Bethlen used this desire to deflect criticism of his economic, social, and political policies.

The Great Depression, which started in 1929, caused living standards to drop. The country's political mood shifted further to the right. In 1932, Horthy appointed Gyula Gömbös as prime minister. Gömbös changed Hungarian policy towards closer cooperation with Germany and began efforts to make the remaining ethnic minorities in Hungary more Hungarian.

Gömbös signed a trade agreement with Germany. This helped Hungary's economy recover from the depression but made Hungary dependent on Germany for raw materials and markets. Adolf Hitler appealed to Hungarian desires to regain lost territories. Extreme right-wing groups, like the Arrow Cross Party, increasingly adopted extreme Nazi policies. They wanted to suppress Jews. The government passed the First Jewish Law in 1938, which limited Jewish involvement in the Hungarian economy.

In 1938, Béla Imrédy became prime minister. Imrédy's attempts to improve Hungary's relations with the United Kingdom at first made him unpopular in Germany and Italy. After Germany's takeover of Austria in March, he realized he could not upset Germany and Italy for long. In the autumn of 1938, his foreign policy became very pro-German and pro-Italian.

Imrédy wanted to gain power in Hungarian right-wing politics. He began to suppress political rivals. The growing Arrow Cross Party was harassed and eventually banned by Imrédy's government. As Imrédy moved further to the right, he suggested reorganizing the government along totalitarian lines. He also drafted a harsher Second Jewish Law. Parliament, under the new government of Pál Teleki, approved the Second Jewish Law in 1939. This law greatly restricted Jewish involvement in the economy, culture, and society. Importantly, it defined Jews by race instead of religion. This change negatively affected those who had converted from Judaism to Christianity.

World War II

During World War II, Hungary was part of the Axis powers. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy supported Hungary's claims to territories it lost in 1920. The two Vienna Awards returned parts of Czechoslovakia and Romania to Hungary. In the 1930s, Hungary relied more on trade with Fascist Italy because its economy had suffered during the Great Depression. This was important because Hungary's foreign debt grew as the government expanded to employ university graduates, who might have caused unrest if unemployed. In 1939, Hungary took over the rest of Carpathian Ruthenia after Czechoslovakia broke up.

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. Earlier, on July 24, Teleki wrote to Hitler that Hungary would not fight against Poland, as it was a matter of national honor.

On November 20, 1940, under pressure from Germany, Teleki made Hungary join the Tripartite Pact. In December 1940, he also signed a short-lived "Treaty of Eternal Friendship" with Yugoslavia. A few months later, after a Yugoslavian coup threatened Germany's planned invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler asked Hungary to support his invasion of Yugoslavia. He promised to return some former Hungarian territories lost after World War I in exchange for cooperation. Unable to stop Hungary from joining the war with Germany, Teleki took his own life. The right-wing radical László Bárdossy became prime minister. After the invasion of Yugoslavia and the creation of the Independent State of Croatia, Hungary annexed Bácska, the rest of Baranya, Prekmurje, and Muraköz.

Hungary did not immediately join the invasion of the Soviet Union, which began on June 22, 1941. Hitler did not directly ask for Hungarian help. Also, Hungary's involvement in Operation Barbarossa in 1941 was limited because the country did not have a large army before 1939, and there was little time to prepare troops. Nevertheless, many Hungarian officials argued for joining the war to encourage Hitler not to favor Romania in future border changes in Transylvania. Romanians had fought Hungarians during the 1848 revolution, causing many conflicts between the two countries. Today, most Hungarians still view Romania negatively.

After war broke out against Russia on the Eastern Front in 1941, many Hungarian officials argued for joining the war on the German side. Hungary entered the war, and on July 1, 1941, the Hungarian Karpat Group advanced far into southern Russia. At the Battle of Uman, the Karpat Group helped surround the 6th Soviet Army and the 12th Soviet Army. Twenty Soviet divisions were captured or destroyed.

Admiral Horthy worried about Hungary's growing reliance on Germany. He forced Bárdossy to resign and replaced him with Miklós Kállay, a conservative from Bethlen's government. Kállay continued Bárdossy's policy of supporting Germany against the Red Army. However, he also secretly started talks with the Western Powers.

In late 1941, the Hungarian army participated in the invasion of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Poland quickly fell, and Hungary allowed 70,000 Polish refugees to enter, which annoyed Hitler. During the Battle of Stalingrad, the Hungarian Second Army suffered terrible losses. Shortly after Stalingrad fell in January 1943, the Hungarian Second Army effectively stopped being a functioning military unit.

Secret talks with the British and Americans continued. Hitler learned of Kállay's deception and feared Hungary might make a separate peace. He ordered Nazi troops to launch Operation Margarethe and occupy Hungary in March 1944. Döme Sztójay, a strong supporter of the Nazis, became the new prime minister with the help of a Nazi military governor. SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann went to Hungary to oversee the large-scale deportations of Jews to German death camps in occupied Poland. Between May 15 and July 9, 1944, Hungarians deported 437,402 Jews to the Auschwitz concentration camp. In August 1944, Horthy replaced Sztójay with the anti-Fascist General Géza Lakatos. Under Lakatos, the acting Interior Minister ordered Hungarian police to prevent any Hungarian citizens from being deported.

In September 1944, Soviet forces crossed the Hungarian border. On October 15, 1944, Horthy announced that Hungary had signed a ceasefire with the Soviet Union. The Hungarian army ignored the ceasefire. The Germans launched Operation Panzerfaust. By kidnapping his son, they forced Horthy to cancel the ceasefire, remove the Lakatos government, and name Ferenc Szálasi, the leader of the Arrow Cross Party, as prime minister. Szálasi became prime minister of a new fascist government, and Horthy resigned. In cooperation with the Nazis, Szálasi restarted the deportations of Jews, especially in Budapest. Thousands more Jews were killed by Hungarian Arrow Cross members. The retreating German army destroyed the rail, road, and communication systems.

On December 28, 1944, a temporary government was formed in Hungary under acting Prime Minister Béla Miklós. Miklós's and Szálasi's rival governments both claimed to be legitimate. The Germans and pro-German Hungarians loyal to Szálasi continued to fight as the territory controlled by the Arrow Cross regime shrank. The Red Army surrounded Budapest on December 29, 1944, and the siege of Budapest began. It continued until February 1945. Most of what was left of the Hungarian First Army was destroyed north of Budapest between January 1 and February 16, 1945. Budapest surrendered to the Soviet Red Army on February 13, 1945.

On January 20, 1945, representatives of the Hungarian provisional government signed a ceasefire in Moscow. Szálasi's government fled the country by the end of March. Officially, Soviet operations in Hungary ended on April 4, 1945, when the last German troops were expelled. On May 7, 1945, General Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of Staff, signed the unconditional surrender of all German forces.

This era was marked by growing anti-Semitism, supported by the state. This led to the deaths of over 400,000 Jews from 1941 to 1945. From 1944 to 1945, the Soviets were driven out, and the Germans occupied Hungary. The war took many lives, and the siege of Budapest was especially devastating.

There were about half a million civilian and military victims of World War II in Hungary, in addition to hundreds of thousands killed in death camps because of their ethnicity. The country's infrastructure was badly damaged, and most of its wealth was taken by the Germans and Soviets. All the recaptured territories were also lost. The Hungarian civilian population suffered even more, with attacks in neighboring countries like Slovakia, Transcarpathia, and especially Vojvodina, leading to forced removals and massacres.

World War II ended with Hungary as a loser. Following the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947, Hungary had an even smaller area than after Trianon. The country, suffering from looting and inflation, was ordered to pay $300 million in damages.

Historian Tamás Stark estimated Hungary's military losses from 1941 to 1945 at 300,000–310,000. This included 110,000–120,000 killed in battle and 200,000 missing or prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. Civilian losses were about 80,000, including 45,500 killed in military campaigns and air attacks, and 28,000 Romani people killed. Jewish Holocaust victims totaled 600,000.

Post-War Communist Period

Transition to Communism (1944–1949)

The Soviet Army occupied Hungary from September 1944 to April 1945. The siege of Budapest lasted almost two months, from December 1944 to February 1945. The city suffered widespread destruction, including the demolition of all Danube bridges by the Germans. In Moscow in November 1944, Hungarian officials met with exiled communists and agreed on a post-war government. Miklós would be premier, and the Communist Party would be legalized and join the government. The provisional national government formed on December 22, 1944, in Debrecen, which was under Soviet control. It reorganized the public sector, began land reform, modernized elementary education, and called for elections.

By signing the Peace Treaty of Paris in 1947, Hungary again lost all the territories it had gained between 1938 and 1941. Neither the Western Allies nor the Soviet Union supported any changes to Hungary's pre-1938 borders, except for three more villages transferred to Czechoslovakia. The Soviet Union took over sub-Carpathia, which is now part of Ukraine.

The Peace Treaty with Hungary, signed on February 10, 1947, declared that the Vienna Award decisions of November 2, 1938, were "null and void." Hungary's borders were set along its 1938 frontiers, with a small loss of territory on the Czechoslovakian border. Many communist leaders from 1919 returned from Moscow. The first major violation of civil rights affected the ethnic German minority. Half of them (240,000 people) were deported to Germany in 1946–1948, even though most had not supported Germany during the war. There was also a forced "exchange of population" between Hungary and Czechoslovakia, involving about 70,000 Hungarians in Slovakia and fewer Slovaks in Hungary. Unlike the Germans, these people could take some of their property with them.

The Soviets initially planned to introduce communism gradually in Hungary. When they set up a provisional government in Debrecen on December 21, 1944, they included representatives from several moderate parties. Following demands from the Western Allies for a democratic election, the Soviets allowed the only truly free election in post-war Eastern Europe in Hungary in November 1945. This was also the first election in Hungary based on universal voting rights.

People voted for party lists. The Independent Smallholders' Party, a center-right peasant party, won 57% of the vote. Despite the hopes of communists and Soviets that giving land to poor peasants would make them popular, the Hungarian Communist Party received only 17% of the votes. The Soviet commander in Hungary, Marshal Voroshilov, refused to let the Smallholders' Party form a government alone. Under his pressure, the Smallholders formed a coalition government including communists, social democrats, and the National Peasant Party. The communists held some key positions. On February 1, 1946, Hungary was declared a republic, and the Smallholders' leader, Zoltán Tildy, became president. He appointed Ferenc Nagy as prime minister. Mátyás Rákosi, leader of the Communist Party, became deputy prime minister. Another leading communist, László Rajk, became minister of the interior, in charge of law enforcement and establishing the Hungarian secret police (ÁVH). The communists constantly pressured the Smallholders both inside and outside the government. They took over industrial companies, banned religious groups, and took key positions in local government. In February 1947, the police began arresting Smallholders Party leaders, accusing them of "conspiracy against the republic." Many prominent figures emigrated or were forced to flee, including Prime Minister Nagy in May 1947. Rákosi later boasted that he had dealt with his government partners "like slices of salami," cutting them off one by one.

In the parliamentary election in August 1947, the communists used widespread election fraud with "blue slips" (absentee ballots). Even so, they only increased their share from 17% to 24% in Parliament. The social democrats, who were now allies of the communists, received 15%, down from 17% in 1945. The Smallholders' Party lost much popularity, ending up with 15%. However, their former voters turned to three new center-right parties that seemed more determined to resist the communists. Their combined share of votes was 35%.

Facing their second election failure, the communists changed tactics. Under new orders from Moscow, they decided to drop democratic appearances and speed up the communist takeover. In June 1948, the Social Democratic Party was forced to "merge" with the Communist Party to create the Hungarian Working People's Party, which the communists controlled. Anti-communist social democrat leaders were forced into exile or removed from the party. Soon after, President Tildy was removed and replaced by a cooperative social democrat, Árpád Szakasits.

Eventually, all "democratic" parties were organized into a "People's Front" in February 1949, losing any remaining independence. Rákosi led the People's Front. Opposition parties were simply declared illegal, and their leaders were arrested or forced into exile. On August 18, 1949, the parliament passed the Hungarian Constitution of 1949, based on the Soviet Union's 1936 constitution. The country's name changed to the People's Republic of Hungary, "the country of the workers and peasants" where "every authority is held by the working people." Socialism was declared the nation's main goal. A new coat of arms with communist symbols like the red star, hammer, and sickle was adopted.

The Stalinist Era (1949–1956)

Rákosi, as chief secretary of the Hungarian Working People's Party, was the de facto leader of Hungary. He had almost unlimited power and demanded complete obedience from party members, including his two closest colleagues, Ernő Gerő and Mihály Farkas. All three had returned to Hungary from Moscow, where they had lived for many years and had close ties to high-ranking Soviet leaders. Their main rivals in the party were the "Hungarian" communists who had led the illegal party during the war and were more popular within the party.

Rajk, their most influential leader, was arrested in May 1949. He was accused of strange crimes, such as spying for Western powers and Yugoslavia (which was also communist but had bad relations with the Soviet Union). At his trial in September 1949, he was forced to confess to being an agent of Horthy, Leon Trotsky, Josip Broz Tito, and Western imperialism. He also admitted to being part of a plot to murder Rákosi and Gerő. Rajk was found guilty and executed. In the next three years, other party leaders considered untrustworthy, like former social democrats or other Hungarian illegal communists such as János Kádár, were also arrested and imprisoned on false charges.

Rajk's show trial is seen as the start of the worst period of Rákosi's rule. Rákosi tried to impose total control over Hungary. The personality cult, focused on him and Joseph Stalin, grew to extreme levels. Rákosi's pictures and statues were everywhere, and all public speakers had to praise his wisdom and leadership. Meanwhile, the secret police, led by Gábor Péter under Rákosi, cruelly persecuted all "class enemies" and "enemies of the people."

An estimated 2,000 people were executed, and over 100,000 were imprisoned. About 44,000 ended up in forced-labor camps, where many died from terrible work conditions, poor food, and almost no medical care. Another 15,000 people—mostly former aristocrats, industrialists, military generals, and other upper-class people—were deported from cities to countryside villages. There, they were forced to do hard farm labor. Some members of the Hungarian Working People's Party opposed these policies, and Rákosi expelled around 200,000 from the organization.

Nationalization

By 1950, the state controlled most of the economy. All large and medium-sized industrial companies, plants, mines, banks, and all retail and foreign trade companies were taken over by the state without any payment. Following Soviet economic policies, Rákosi declared that Hungary would become a "country of iron and steel," even though Hungary had no iron ore. The forced development of heavy industry was for military purposes, preparing for a war against "Western imperialism." A huge amount of the country's resources was spent on building entirely new industrial cities and plants from scratch, even though much of the country was still in ruins from the war. Hungary's traditional strengths, like agriculture and textile industries, were ignored.

Large agricultural estates were divided and given to poor peasants in 1945. In farming, the government tried to force independent peasants to join cooperatives, where they would become paid laborers. But many resisted stubbornly. The government responded with ever-higher demands for compulsory food quotas on peasants' produce. Rich peasants, called 'kulaks,' were declared "class enemies" and suffered all kinds of unfair treatment, including imprisonment and loss of property. This removed some of the most skilled farmers from production. The decline in farm output led to a constant shortage of food, especially meat.

Rákosi quickly expanded the education system in Hungary. This was an attempt to replace the old educated class with what Rákosi called a new "working intelligentsia." Besides effects like better education for the poor, more opportunities for working-class children, and increased literacy, this also spread communist ideas in schools and universities. Also, as part of efforts to separate church and state, almost all religious schools were taken over by the state. Religious instruction was called backward propaganda and gradually removed from schools.

Hungarian churches were systematically intimidated. Cardinal József Mindszenty, who had bravely opposed the German Nazis and Hungarian Fascists during World War II, was arrested in December 1948 and accused of treason. After five weeks in jail, he confessed to the charges and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Protestant churches were also purged, and their leaders were replaced by those loyal to Rákosi's government.

The Hungarian military quickly held public, pre-arranged trials to remove "Nazi remnants and imperialist saboteurs." Several officers were sentenced to death and executed in 1951, including Lajos Toth, a famous fighter pilot from World War II, who had returned from U.S. captivity to help revive Hungarian aviation. The victims were cleared of charges after communism fell.

Preparations for a show trial began in Budapest in 1953 to "prove" that Raoul Wallenberg had not been taken to the Soviet Union in 1945 but was a victim of "cosmopolitan Zionists." For this show trial, three Jewish leaders and two supposed "eyewitnesses" were arrested and tortured. The show trial was started in Moscow, following Stalin's anti-Zionist campaign. After Stalin and Lavrentiy Beria died, the preparations for the trial stopped, and the arrested people were released.

Rivalry Among Communist Leaders

Rákosi's economic priorities were developing military and heavy industry and paying war compensation to the Soviet Union. Improving living standards was not a priority, so Hungarians saw their living standards fall. Although his government became very unpopular, he held firm power until Stalin died on March 5, 1953. A confused power struggle then began in Moscow. Some Soviet leaders saw how unpopular the Hungarian government was and ordered Rákosi to give up his position as prime minister. He was replaced by another former communist-in-exile in Moscow, Imre Nagy, who was Rákosi's main opponent in the party. However, Rákosi kept his position as general secretary of the Hungarian Working People's Party. Over the next three years, the two men fought bitterly for power.

As Hungary's prime minister, Nagy slightly reduced state control over the economy and media. He encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. To improve general living standards, he increased the production of consumer goods and reduced taxes and quotas for peasants. Nagy also closed forced-labor camps, released most political prisoners (communists were allowed back into the party), and controlled the secret police. Their hated head, Gábor Péter, was convicted and imprisoned in 1954. These moderate reforms made him very popular in the country, especially among peasants and left-wing intellectuals.

Following a change in Moscow, where Georgy Malenkov, Nagy's main supporter, lost the power struggle against Nikita Khrushchev, Rákosi began to attack Nagy. On March 9, 1955, the central committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party condemned Nagy for "rightist deviation." Hungarian newspapers joined the attacks, and Nagy was blamed for the country's economic problems. On April 18, he was removed from his post by a unanimous vote of the National Assembly. Soon after, Nagy was even expelled from the party and temporarily left politics. Rákosi once again became the unchallenged leader of Hungary.

Rákosi's second period of rule did not last long. His power was weakened by a speech Khrushchev made in February 1956. Khrushchev criticized the policies of Stalin and his followers in Eastern Europe, especially attacks on Yugoslavia and the promotion of personality cults. On July 18, 1956, visiting Soviet leaders removed Rákosi from all his positions, and he flew to the Soviet Union, never to return to Hungary. But the Soviets made a big mistake by appointing his close friend and ally Gerő as his successor, who was equally unpopular.

Rákosi's fall led to much talk of reform both inside and outside the party. Rajk and others who were victims of the 1949 show trial were cleared of all charges. On October 6, 1956, the party allowed a reburial, which tens of thousands of people attended. It became a silent protest against the regime's crimes. On October 13, it was announced that Nagy had been reinstated as a party member.

The 1956 Revolution

On October 23, 1956, a peaceful student demonstration in Budapest presented 16 demands for reform and greater political freedom. When students tried to broadcast these demands, the State Protection Authority made arrests and tried to disperse the crowd with tear gas. When students tried to free those arrested, the police opened fire, starting a chain of events that led to the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

That night, army officers and soldiers joined the students in Budapest. Stalin's statue was pulled down, and protesters chanted "Russians go home," "Away with Gerő," and "Long live Nagy." The central committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party responded by asking for Soviet military help and deciding that Nagy should lead a new government.

Soviet tanks entered Budapest early on October 24. On October 25, Soviet tanks opened fire on protesters in Parliament Square. Shocked by these events, the central committee forced Gerő to resign and replaced him with Kádár.

Nagy announced on Radio Kossuth that he had taken over the government. He promised "the far-reaching democratization of Hungarian public life, the realization of a Hungarian road to socialism in accord with our own national characteristics, and the realization of our lofty national aim: the radical improvement of the workers' living conditions." On October 28, Nagy and his supporters, including Kádár, managed to take control of the Hungarian Working People's Party. At the same time, revolutionary workers' councils and local national committees formed across Hungary.

The change in party leadership was reflected in the government newspaper Szabad Nép ("Free People"). On October 29, the newspaper welcomed the new government and openly criticized Soviet attempts to influence Hungary. Radio Miskolc supported this view, calling for Soviet troops to leave immediately. On October 30, Nagy announced he was freeing Cardinal Mindszenty and other political prisoners. He also told the people that his government planned to end the one-party state. This was followed by statements from other leaders about bringing back the Smallholders Party, the Social Democratic Party, and the Petőfi (former Peasants) Party.

Nagy's most controversial decision was on November 1, when he announced that Hungary intended to leave the Warsaw Pact and declared Hungarian neutrality. He asked the United Nations to get involved in Hungary's dispute with the Soviet Union. On November 3, Nagy announced details of his coalition government, which included communists, Smallholders, Social Democrats, and Petőfi Peasants. Pál Maléter was appointed minister of defense.

Khrushchev became increasingly worried about these events. On November 4, 1956, he sent the Red Army into Hungary. Soviet tanks quickly captured Hungary's airfields, highway junctions, and bridges. Fighting happened across the country, and Hungarian forces were quickly defeated. During the Hungarian Uprising, an estimated 20,000 people were killed, almost all during the Soviet intervention. Nagy was arrested and imprisoned until his execution in 1958. Other government ministers or supporters were also executed or died in captivity.

The Kádár Era After the Revolution (1956–1989)

Once in power, Kádár attacked the revolutionaries. 21,600 people were imprisoned, 13,000 were held without trial, and 400 were killed. But in the early 1960s, Kádár announced a new policy: "He who is not against us is with us." This was a change from Rákosi's harsh statement, "He who is not with us is against us." Kádár declared a general amnesty, slowly reduced the secret police's power, and introduced more liberal cultural and economic policies. These aimed to overcome the hostility towards him and his government after 1956.

In 1966, the central committee approved the "New Economic Mechanism." This aimed to rebuild the economy, increase productivity, make Hungary more competitive in world markets, and create prosperity for political stability. Over the next two decades of relative peace, Kádár's government responded to calls for small political and economic reforms, as well as to opposition from those against reform. By the early 1980s, it had achieved some lasting economic reforms and limited political freedom. It also pursued a foreign policy that encouraged more trade with the West. However, the New Economic Mechanism led to growing foreign debt, used to support unprofitable industries.

Hungary's move to a Western-style democracy was one of the smoothest among the former Soviet bloc countries. By late 1988, activists within the party and government, and intellectuals in Budapest, increased pressure for change. Some became reform socialists, while others started movements that would become new parties. Young liberals formed the Federation of Young Democrats (Fidesz). A core group from the "democratic opposition" formed the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ). The national opposition created the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF). Public activism grew to a level not seen since the 1956 revolution.

End of Communism

In 1988, Kádár was replaced as general secretary of the Communist Party, and reform communist leader Imre Pozsgay joined the politburo. In 1989, the Parliament passed a "democracy package." This included allowing multiple trade unions, freedom of association, assembly, and the press, a new election law, and a major change to the constitution in October 1989. Since then, Hungary has reformed its economy and increased its connections with Western Europe. It became a member of the European Union in 2004.

A central committee meeting in February 1989 agreed in principle to a multi-party political system. It also called the October 1956 revolution a "popular uprising," in the words of Pozsgay, whose reform movement had been gaining strength as Communist Party membership dropped sharply. Kádár's main political rivals then worked together to move the country gradually towards democracy. The Soviet Union reduced its involvement by signing an agreement in April 1989 to withdraw Soviet forces by June 1991.

National unity reached its peak in June 1989 when the country re-buried Nagy, his associates, and, symbolically, all other victims of the 1956 revolution. A Hungarian National Round Table, with representatives from new parties, some re-created old parties, the Communist Party, and different social groups, met in late summer 1989. They discussed major changes to the Hungarian constitution to prepare for free elections and a transition to a fully free and democratic political system.

In October 1989, the Communist Party held its last congress and renamed itself the Hungarian Socialist Party. In a historic session from October 16–20, 1989, the Parliament passed laws for multi-party parliamentary elections and a direct presidential election. The laws changed Hungary from a People's Republic to the Republic of Hungary. They guaranteed human and civil rights and created a system that separates powers among the judicial, executive, and legislative branches of government. On the anniversary of the 1956 Revolution, October 23, the Hungarian Republic was officially declared by the provisional President Mátyás Szűrös, replacing the Hungarian People's Republic. The revised constitution also supported "values of bourgeois democracy and democratic socialism" and gave equal status to public and private property.

The Third Republic (Since 1989)

Foundation

The first free parliamentary election, held in May 1990, was like a public vote on communism. The revitalized communists did poorly, even though they had advantages as the "incumbent" party. Populist, center-right, and liberal parties did best. The MDF won 43% of the vote, and the SZDSZ got 24%. Under Prime Minister József Antall, the MDF formed a center-right coalition government with the Independent Smallholders' Party and the Christian Democratic People's Party. They had a 60% majority in parliament. Opposition parties included SZDSZ, the Hungarian Socialist Party, and Fidesz.

By June 1991, Soviet troops left Hungary. About 100,000 Soviet military and civilian personnel were stationed in Hungary, with about 27,000 pieces of military equipment. The withdrawal used 35,000 railway cars. The last units crossed the Hungarian-Ukrainian border.

Péter Boross became prime minister after Antall died in December 1993. The Antall/Boross coalition governments tried to create a well-functioning parliamentary democracy and a market economy. They also had to manage the political, social, and economic problems from the collapse of the communist system. The huge drop in living standards led to a massive loss of political support.

In the May 1994 election, the Socialists won the most votes and 54% of the seats, with Gyula Horn as the new Prime Minister. Their campaign focused on economic issues and the big drop in living standards since 1990. This showed a desire to return to the relative security and stability of the socialist era. However, voters rejected both right-wing and left-wing extreme solutions. After its disappointing result, the Fidesz party decided to change its ideas from liberal to conservative. This caused a big split in the party, and many members left for the other liberal party, the SZDSZ, which formed a coalition with the socialists, giving them more than a two-thirds majority.

Economic Reform

The coalition was influenced by Horn's socialism, by its economic experts (who had studied in the West), and by its liberal coalition partner, the SZDSZ. Facing the threat of state bankruptcy, Horn started economic reforms and aggressive privatization of state companies to multinational companies. This was done in exchange for promises of investment (for reconstruction, expansion, and modernization). The socialist-liberal government adopted a strict economic program, the Bokros package, in 1995. This had dramatic effects on social stability and quality of life. The government introduced university tuition fees and partly privatized state services. It also supported science. The government pursued a foreign policy of joining Euro-Atlantic organizations and improving relations with neighboring countries. Critics argued that the ruling coalition's policies were more right-wing than those of the previous right-wing government.

The Bokros package and privatization efforts were unpopular with voters. Rising crime rates, accusations of government corruption, and an attempt to restart the unpopular project of building a dam on the Danube also caused dissatisfaction. This led to a change in government after the 1998 parliamentary elections.

After a disappointing result in the 1994 elections, Fidesz, led by Viktor Orbán, changed its political position from liberal to national conservative. It added "Hungarian Civic Party" to its name. This conservative shift caused a big split in the party. Péter Molnár, Gábor Fodor, and Klára Ungár left the party and joined the SZDSZ. Orbán's Fidesz party won the most parliamentary seats in the 1998 election and formed a coalition with the Smallholders and the Democratic Forum.

First Government of Viktor Orbán: 1998–2002

The government led by Orbán promised faster growth, lower inflation, and lower taxes. It inherited an economy with good signs, including a growing export surplus. The government removed tuition fees and aimed to create good market conditions for small businesses. It also encouraged local production using domestic resources. In foreign policy, the Orbán government continued to prioritize joining Euro-Atlantic organizations. However, it was a stronger advocate for the rights of ethnic Hungarians living abroad than the previous government. As a result of a 1997 vote, Hungary joined NATO in 1999. In 2002, the European Union agreed to admit Hungary along with 9 other countries as members on January 1, 2004.

Fidesz was criticized by its opponents for how it presented history, especially the fall of communism in 1989. Fidesz suggested that the Socialist party was the moral and legal successor to the hated communist state party. The socialists, however, argued that they had pushed for change from within. They criticized Fidesz members for taking all the credit for the fall of communism.

In the 2002 election, the MSZP/SZDSZ left-wing coalition narrowly beat the Fidesz/MDF right-wing coalition in a fierce political fight. Voter turnout was very high at 73%. Péter Medgyessy became prime minister.

MSZP: 2002–2010