History of Inuit clothing facts for kids

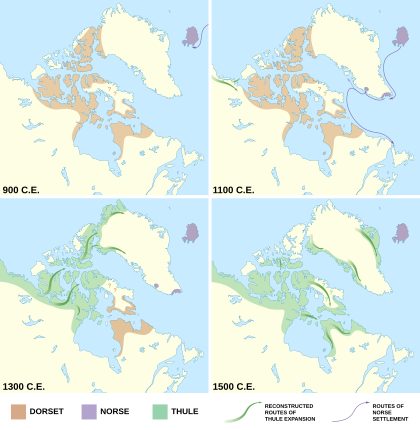

The history of Inuit clothing goes way back, even before written records. Clothes made by Inuit people haven't changed much over thousands of years. People across the Arctic, like the Inuit, Iñupiat, and Siberian groups, all have similar clothing styles. Tools and small statues found by archaeologists suggest these clothing ideas might have started in Siberia around 22,000 BCE. In northern Canada and Greenland, similar clothing systems appeared around 2500 BCE. Clothes found from the years 1000 to 1600 CE look very much like clothes from the 1600s to the mid-1900s. This shows how consistent Inuit clothing design has been for centuries.

Starting in the late 1500s, Inuit people began meeting traders and explorers from other parts of the world. These meetings slowly changed Inuit clothing. New tools and fabrics from outside became part of their traditional clothing. Sometimes, ready-made fabric clothes even replaced traditional animal skin outfits. Often, Inuit wore these new clothes because others expected them to. But many Inuit also liked the new fabric clothes because they were convenient. When Inuit chose to wear these new styles, it sometimes led to traditional clothing styles disappearing.

In the early 1900s, as more people moved to modern ways of life, fewer traditional skin garments were made for everyday use. This happened because people lost the skills to make them, and fewer people wanted them. Schools, especially the Canadian Indian residential school system, stopped older Inuit from teaching younger generations how to make clothes. Also, manufactured clothing became easier to find, and animal furs were harder to get. All these things together meant that by the 1990s, almost no one knew how to make traditional Inuit clothing anymore.

Since then, Inuit groups have worked hard to save these old skills. They are teaching them to younger people in ways that fit with modern life. While full traditional skin outfits are not common for daily wear, people still wear them in winter or for special events. Many Inuit seamstresses now use modern materials to make clothes that look traditional. This has led to a new Inuit fashion movement. However, as Inuit clothing becomes part of the wider fashion world, Inuit groups are worried about protecting their culture. They want to prevent others from copying their traditional garments, like the amauti, without permission.

Contents

Ancient Clothing Styles

Studying old Inuit clothing helps us understand where their unique skin clothing system came from. It's rare to find whole animal skin clothes at old sites because animal hides decay easily. So, it's hard to know exactly when Arctic skin clothing began. Scientists usually learn about the first clothing from sewing tools and art found at these sites.

In Siberia, archaeologists found small carved statues that seem to wear tailored skin clothes. These statues are very old, suggesting that clothing like the Inuit wear might have been used in Siberia as far back as 22,000 BCE. Small ivory statues from the Dorset culture, an ancient Inuit group in northern Canada (500 BCE to 1500 CE), also show what look like parkas, underwear, and Inuit boots called kamiit. Some of these Dorset figures have high collars instead of hoods. It's not clear if their parkas had no hoods or if the hoods were just down.

Tools for preparing and sewing animal skins have been found in northern North America and Greenland. These tools, made of stone, bone, and ivory, are like those the Inuit used later. This confirms that skin clothing was made there as early as 2500 BCE. Interestingly, no sewing needles were found at summer camps. This might mean the Dorset people had rules against making caribou clothing at coastal sites, just like the later Inuit did. Evidence of seal processing by the Dorset culture was found in Newfoundland and Labrador. This site was used for about 800 years, from 50 BCE to 770 CE.

Small statues from the Thule culture (1000 to 1600 CE) found in Nunavut, Canada, also show features of skin clothing. One ivory figure shows chest straps like those on a woman's parka, called an amauti. A wooden figure from Ellesmere Island even has tiny bear skin trousers! This was very unusual for ancient statues. Thule-era ivory figures from Igloolik show the large hoods and rounded tails typical of women's amauti.

Sometimes, pieces of frozen skin clothes, or even whole outfits, are found at archaeological sites. It's hard to know exactly how old they are because they are so fragile. Most are thought to be from the Thule culture (1000 to 1600 CE). Even though styles like hood height and flap size have changed, the basic patterns, seam locations, and stitching are very similar to clothes from the 1600s to the mid-1900s. This proves that Inuit clothing construction has been very consistent for centuries. For example, a boot sole from Kimmirut, Nunavut, from 200 CE, is made in the exact same style as modern boots.

Thule-era clothes are also very similar to later items. This suggests that the Inuit skin clothing system grew directly from the Thule system. On Devon Island in Nunavut, pieces of frozen skin clothing, including a child's mitten, were found in 1985. These items, from around 1000 CE, have patterns and stitching that match modern clothes. Other clothing items, like a kamleika (an overcoat made of gut-skin), were found on Ellesmere Island in 1978. They are from 1200 CE and are like gut-skin coats from the 1900s.

In 1972, eight well-preserved mummies wearing full outfits were found at Qilakitsoq in Greenland. They are from around 1475. Research shows their clothes were made and sewn just like modern skin clothing from the Kalaallit people of that area. In Alaska, clothing made of caribou and polar bear skin was found from the Kakligmiut Iñupiat group, dating from 1510–1826. These clothes also show little change in construction between 1500 and 1850.

Throughout history, Inuit groups shared clothing designs and styles with each other. They also learned from other Arctic peoples like the Chukchi and Yupik from Siberia, the Sámi people from Scandinavia, and other Indigenous groups in North America. There's evidence that ancient Inuit gathered at large trade fairs to swap materials and finished goods. This trade network covered about 3,000 kilometers (1,860 miles) of Arctic land.

European Contact

It's hard to know exactly when Europeans first met the Inuit because there aren't many records. The Norse people had settlements in Greenland from 986 to about 1410. The Thule people started moving there from North America around 800. It's believed they met after 1150. Old records and archaeology show that these groups traded and sometimes fought. The Norse didn't seem to adopt Inuit clothes or hunting methods.

For centuries after that, Europeans had little contact with the Inuit. Sometimes, sailors would kidnap Inuit from Labrador and take them to Europe to be shown off and studied. The Europeans would sometimes draw pictures and write about their captives, especially their clothes. The earliest known European pictures of living Inuit were printed in Germany in 1567. They show an Inuit woman and her child who were kidnapped from Labrador in 1566.

The first big increase in contact with the Inuit happened because of Martin Frobisher's trips. From 1576 to 1578, he tried to find the Northwest Passage in the North American Arctic. This meant he had to meet the Inuit. After him, hundreds of European ships came to hunt seals and whales, trade with the Inuit, and keep looking for the Northwest Passage. Europeans kept writing about Inuit clothing, creating the first detailed pictures of their garments. The clothing styles they drew stayed mostly the same over the centuries. For example, the 1567 pictures are similar to a 1654 painting of Kalaallit Inuit in traditional skin clothing. And those clothes are like the ones found with the mummies at Qilakitsoq.

After Frobisher and others arrived, contact with non-Inuit people, especially traders and explorers from America, Europe, and Russia, began to change Inuit clothing more. Foreigners brought things like steel needles, fabric, and ready-made European clothes. While these imported clothes never fully replaced traditional Inuit clothing, they became very popular in many areas. Small figures carved by Inuit after this contact show that fabric clothing was widely adopted. Often, Christian missionaries encouraged Inuit to wear outside clothes.

International trade, especially the fur trade and whaling, also caused unwanted changes to Inuit clothing. After setting up a trading post in Alaska in 1783, Russian traders stopped the local Inuit from using sea otter and bear furs for traditional clothes. They wanted to sell these valuable furs overseas. Similarly, in the mid-1800s, Inuit in West Greenland started selling their furs instead of making clothes from them. This was because the new money-based economy made it hard to keep their traditional way of life. After whaling grew in the Canadian Arctic around the mid-1800s, many Inuit men worked on whaling ships. The whaling season lasted until November, which was when they usually hunted caribou. This meant many men couldn't get enough caribou skins for warm winter clothes. This then limited their ability to hunt in winter, sometimes leading to their families starving.

Choosing New Clothes

Even though outside pressure often led to wearing foreign clothes, many Inuit also chose to adopt new materials and garments themselves. They would trade or buy ready-made fabric and clothing. In Canada, these items often came from the Hudson's Bay Company. In Greenland, they came from the Royal Greenland Trading Department. Men especially adopted ready-made cloth clothes more easily than women, because there were good foreign options for most men's clothing. In Greenland, many Inuit men quickly started wearing lopapeysa, which are traditional Icelandic sweaters. Men from the Nunavimiut group in Ungava Bay wore crocheted woolen hats under their hoods. Most Inuit men working on whaling ships wore cloth clothes completely during the summer, keeping only their waterproof sealskin kamiit (boots).

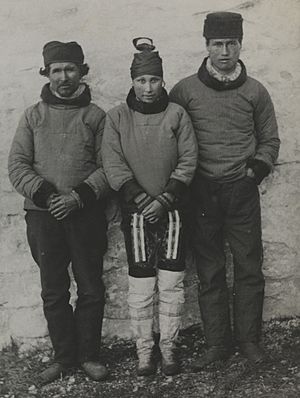

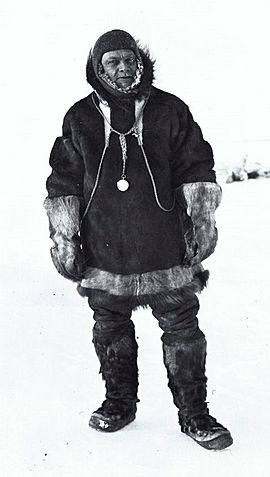

Sometimes, Europeans also adopted Inuit clothing. Whalers would sometimes wear Inuit garments for Arctic travel. They even hired whole Inuit families to travel with them and sew skin clothing. People at the time noted that this helped reduce deaths from cold on whaling ships. Canadian explorers Diamond Jenness and Vilhjalmur Stefansson lived with the Inuit during the Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913–1916). They wore Inuit clothing and studied how it was made. The Scandinavian team of the Fifth Thule Expedition (1922–1924) did the same.

While Inuit men easily adopted outside clothing, the women's amauti (a parka designed for mothers) had no ready-made European equivalent. So, Inuit women used purchased cloth to make clothes that fit their needs. Starting in the mid-1800s, the Iñupiaq people of northern Alaska began using colorful cotton fabrics like drill and calico to make over-parkas. These protected their caribou clothes from dirt and snow. Men's versions were shorter, while women's were calf-length with ruffles. In Iñupiaq, these are called atikłuk, and in Inuktitut (spoken in Canada), they are called silapaaq. The longer women's version eventually moved east to the Northwest Territories. There, it became known as the cloth parka or Mother Hubbard parka (named after a European dress). The Mother Hubbard parka was first worn over or under the fur amauti. Later styles were insulated with duffel cloth or fur and could be worn on their own, especially in summer. Women liked these garments because they were much simpler to make than skin clothing. Their new materials were also seen as a sign of wealth.

When Inuit chose to adopt outside clothing styles, it often led to traditional styles disappearing in many areas. Inuit from different groups often met at camps and trading posts set up by Europeans. They shared their techniques and styles, which made local clothing differences less noticeable. In the 1880s, a trading post on the east coast of Greenland made foreign clothes much more available. This led to traditional Inuit skin garments in that area becoming simpler and less common. In 1914, the Canadian Arctic Expedition arrived in the area of the Copper Inuit, who had been isolated. This led to the unique Copper Inuit clothing style almost disappearing. By 1930, it was nearly completely replaced by a mix of styles brought by new immigrants and European-Canadian clothing, especially the Mother Hubbard parka. Even though the Mother Hubbard only arrived there in the late 1800s, it became so popular that it is now seen as the traditional women's garment in those areas.

Changes Since the 1800s

Making traditional skin garments for everyday use has declined in the 1900s and 2000s. This is because people lost the skills, and fewer people wanted them. Changes in lifestyle due to outside influences were a big reason for this decline. This was most noticeable in the 1800s and 1900s when more non-Inuit missionaries, researchers, explorers, and government officials came to Inuit communities.

Few modern Inuit live the nomadic hunting and trapping lifestyle of their ancestors. Instead, they spend much of their time indoors in heated buildings. Many Inuit in Northern Canada work outdoor industrial jobs where fur clothing, especially kamiit (boots), would not be practical. Buying manufactured clothing saves time and energy compared to the hard work of making traditional skin clothing. It can also be easier to take care of.

The Canadian Indian residential school system in northern Canada, which started with Christian mission schools in the 1860s, greatly harmed the way elders passed down knowledge to younger generations. Children sent to residential schools or hostels were often separated from their families for years. These schools did little to include their language, culture, or traditional skills. Children who lived at home and went to day schools were at school for long hours. This left little time for families to teach them traditional clothing-making and survival skills. Until the 1980s, most northern day schools did not teach Inuit culture, which made the cultural loss even worse. The time for traditional skills was further reduced in areas with strong Christian influence, as Sundays were seen as a day of rest for church, not for work. Without time or interest to practice, many younger people lost interest in making traditional clothing.

The availability of animal furs also affected the making of skin garments. In the early 1900s, too much hunting led to a big drop in caribou herds in some areas. A lack of materials after the 1940s caused a style of baggy leggings or stockings worn by some Inuit groups to disappear. Many areas today have hunting rules that affect how many furs are available. Greenland, for example, requires a hunting license, limits the number of animals that can be hunted, and sets hunting seasons.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, strong protests against seal hunting from animal rights groups, especially a big Greenpeace Canada campaign in 1976, led to strict rules. These rules limited the import of sealskin goods in the United States (1972) and Europe (1983). These rules crashed the market for seal furs and caused a big drop in hunting as a main job. This reduced the furs available for northern seamstresses and increased poverty. Inuit income levels dropped by about 95% compared to before the bans.

Greenpeace Canada apologized to Inuit in 1985 for the problems caused by their campaign. The European Union ban on seal products was confirmed again in 2009. In 2015, exceptions were made for certified Indigenous-hunted products, but a 2020 report said this exception didn't help much economically. The sealskin ban has never been removed or made less strict in the United States. Many Inuit have said that efforts to ban seal hunting and sealskin are short-sighted and don't understand their culture.

All these things together meant less demand for elders to make skin garments. This made it less likely that they would pass on their skills. By the mid-1990s, the skills needed to make Inuit skin clothing were almost completely lost. At the same time, more traditional clothing started appearing in Inuit art. This might have been a way to show feelings of cultural loss.

Bringing Back Traditions

Since the 1990s, Inuit groups have worked hard to save traditional skills and teach them to younger generations in a way that fits modern life. Many old barriers to learning traditional knowledge have been removed. By the 1990s, residential schools and the hostel system in the Yukon and Northwest Territories were completely gone. In northern Canada, many schools now offer courses that teach traditional skills and cultural topics.

Outside of formal schools, cultural programs like Miqqut and Traditional Skills Workshop have helped teach modern Inuit how to make traditional clothing. These programs are led by groups like Pauktuutit (Inuit Women of Canada) and Ilitaqsiniq (Nunavut Literacy Council). Sewing groups and classes are popular in northern communities. Many museums now work with Inuit communities to share knowledge and offer training.

From 2016 to 2020, the Canadian government gave $5.7 million to support sealing and sealskin crafts in Indigenous communities. This effort was promoted by Hunter Tootoo, an Inuit Member of Parliament, who often wears sealskin ties and vests. The money has been used for sewing workshops like Nattiq Sealebration. This program teaches professional sewing skills and business practices. The goal is to boost the local market for fur products and support Inuit artists. In 2017, the Canadian government made May 20 National Seal Products Day to support Indigenous sealskin products.

On a practical level, modern techniques make clothing production easier and faster. This makes it simpler for new seamstresses to learn. Prepared skins are available in many northern stores today, so seamstresses can buy the materials they need directly. Wringer washing machines can be used to soften hides. Household chemicals like bleach can make soft white leather when rubbed on skins. Sewing machines and serger machines make stitching more consistent and less time-consuming. Many women follow traditional patterns to make traditionally-styled garments from new materials like cloth, mixing old and new techniques.

Modern Inuit Style

Today, many Inuit wear a mix of traditional skin garments, clothes made with traditional patterns but new materials, and mass-produced imported clothing. What they wear depends on the season, weather, what's available, and what they think is stylish. The fabric-based atikłuk and the Mother Hubbard parka are still popular in Alaska and Northern Canada. Mothers from all walks of life still use the amauti, which can be worn over fabric leggings or jeans. Both handmade and store-bought clothes might have logos and images from traditional or modern Inuit culture. These could be Inuit organizations, sports teams, music groups, or common northern foods.

Store-bought clothes are often changed or adjusted. Seamstresses might add fur ruffs to the hoods of store-bought winter jackets. Boot tops made of skin can be sewn to mass-produced rubber boot bottoms. This creates a boot that is warm like skin clothing but also waterproof and grippy like artificial materials. Traditional patterns might be changed for modern needs. For example, amauti are sometimes made with shorter tails for comfort while driving.

Even though it's not common for Inuit to wear full traditional skin outfits every day, fur boots, coats, and mittens are still popular in many Arctic places. Skin clothing is best for winter, especially for Inuit who work outdoors in traditional jobs like hunting and trapping, or modern jobs like scientific research. Traditional skin clothing is also worn for special events like drum dances, weddings, and holidays. The ceremonial clothing of the Copper Inuit, which had disappeared, has now been brought back for drum gatherings and other special occasions. Modern Inuit in Igloolik celebrate Qaqqiq, the Return of the Sun, with a fashion show of caribou skin and cloth garments. For many modern people, sewing still connects them to Inuit spirituality.

Even clothes made from woven or synthetic fabric today follow ancient shapes and styles. This makes them both traditional and modern at the same time. Modern Inuit clothing has been studied as an example of sustainable fashion and unique local design. Much of the clothing worn by Inuit in the Arctic today is a "blend of tradition and modernity." One expert, Betty Issenman, says that wearing traditional fur clothing is not just practical. It's also a "visual symbol" that shows someone is part of a strong and respected society with very old roots.

Modern Fashion

Inuit-Led Fashion

Starting in the 1990s, Pauktuutit (Inuit Women of Canada) began to promote Inuit fashion and culture outside the Canadian Arctic. They worked with Canadian museums, exhibitions, and festivals to show off clothes designed by Inuit. People liked these events. In 1998, Pauktuutit started a program called "The Road to Independence." Its goal was to help Inuit women become financially independent by teaching them how to design, make, and sell clothes in the modern fashion world. The program was successful, but it also raised concerns. People worried that traditional Inuit clothing, especially the woman's parka or amauti, might be copied and used by non-Inuit without permission. This has happened with other Inuit creations like kayaks, parkas, and even kamiit (boots).

In 1999, American designer Donna Karan of DKNY sent people to the western Arctic to buy traditional garments, including amauti. They wanted to use these as inspiration for a new clothing collection. Her representatives didn't tell the local Inuit why they were there. The Inuit only found out after a journalist contacted the Inuit women's group Pauktuutit for a comment. Pauktuutit said the company's actions were unfair. They said "the fashion house took advantage of some of the less-educated people who did not know their rights." The items they bought were shown in the company's New York store. Pauktuutit believed this was done without the seamstresses' knowledge or permission. After Pauktuutit organized a successful letter-writing campaign, DKNY canceled the planned collection.

In 2001, after the Road to Independence project and the DKNY problem, Pauktuutit started the Amauti Project. This project aimed to find ways to legally protect the amauti. It is seen as traditional knowledge owned by all Inuit women. After talking with many Inuit seamstresses, the project concluded that "All Inuit own the amauti collectively." However, individual seamstresses might use specific designs passed down through their families. To protect this shared cultural ownership, Pauktuutit has asked the Canadian government and the World Intellectual Property Organization to create a special protected status for the amauti. As of 2020, no such protection has been made.

The growth of Inuit fashion is supported by national groups like Pauktuutit and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Local groups like the Nunavut Arts and Crafts Association also help. Modern Inuit fashion has been shown in art exhibitions and fashion shows both in the Arctic and outside. In 2016, an art group in Quebec showed modern sealskin fashion by Inuit designers. In 2017, Martha Kyak was the first Inuit designer to be featured at a big Indigenous fashion show in Ottawa. Inuit designers Victoria Kakuktinniq and Melissa Attagutsiak were invited to show their work at Paris Fashion Week in March 2019. In 2020, the Winnipeg Art Gallery opened an exhibition called Inuk Style showing both old and new Inuit fashion. Kakuktinniq also showed her designs at New York Fashion Week in February 2020.

Materials and Style

Inuit fashion is part of the larger Indigenous American fashion movement. Modern Inuit designers use a mix of new and old materials to create clothes in both traditional and modern shapes. Victoria Kakuktinniq's work, which has greatly influenced modern Inuit fashion, focuses on parkas with traditional styles. Melodie Haana-SikSik Lavallée has combined satin with sealskin to make items from "Victorian gowns to 60s-inspired suits." Many designers also make jewelry from local materials like bone.

Some designers highlight parts of Inuit culture through the look of their products. Artist Becky Qilavvaq has made clothes printed with Inuit song lyrics and pictures of traditional tools. Designer Adina Tarralik Duffy has made onesies and leggings printed with the designs from common northern food products like Pilot Biscuits and Klik canned ham. Martha Kyak's clothing uses geometric designs that came from traditional Inuit tattooing.

Designers who focus on traditional materials like sealskin often do so to support Inuit culture and promote sustainable fashion. Designer Rannva Simonsen, who moved to Nunavut in 1997, has worked with sealskin since 1999. Nicole Camphaug started by sewing sealskin scraps to her own boots. Eventually, friends and family asked for their own, and she started selling seal-trimmed shoes. Using sealskin, a traditional Inuit clothing material, has been debated by non-Inuit. This is because of anti-sealing campaigns by animal rights groups like Greenpeace Canada and PETA. Since the late 2010s, some designers have said that Canadians outside the Arctic seem to be more supportive of Inuit sealskin fashion.

Online selling, especially through social media sites like Facebook, has helped Inuit-designed clothing become popular and sell outside northern communities. This has sometimes caused problems. Inuit crafters and clothing designers have had sales listings for seal products blocked on social media sites. Throat singer Tanya Tagaq had her Facebook account temporarily stopped in 2017 after posting a photo of a sealskin coat. Facebook apologized and fixed the issue within hours.

Non-Inuit Clothing Companies

The connection between traditional Inuit clothing and the modern fashion industry has often been difficult. Inuit seamstresses and designers have described times when non-Inuit designers used traditional Inuit designs and clothing styles without asking permission or giving credit. In some cases, designers changed original Inuit designs in a way that changed their cultural meaning. But they still labeled the products as if they were truly Inuit. Inuit designers have criticized this practice as cultural appropriation.

In 2015, a design company in London called KTZ released a collection with many Inuit-inspired clothes. One sweater in particular had designs taken directly from old photos of a unique caribou parka worn by an Inuit shaman. This garment, known as the Shaman's Parka, is well-known to people who study Inuit culture. It was designed in the late 1800s by the angakkuq (shaman) Qingailisaq and sewn by his wife, Ataguarjugusiq. Qingailisaq or his son, the angakkuq Ava, sold the coat in 1902. It ended up in the American Museum of Natural History. Its detailed designs were inspired by spiritual visions. Ava's great-grandchildren criticized KTZ for not getting permission to use the design from his family. After the media reported the criticism, KTZ apologized and removed the item from sale.

Some brands have tried to work directly with Inuit designers. In 2019, Canadian winterwear brand Canada Goose launched Project Atigi. They asked fourteen Canadian Inuit seamstresses to each design a unique parka or amauti using materials from Canada Goose. The designers kept the rights to their designs. The parkas were shown in New York City and Paris before being sold. The money from the sales, about $80,000, was given to the national Inuit organization Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK). Some Inuit designers criticized the first Project Atigi for not being advertised enough to potential applicants.

The next year, the company released a bigger collection called Atigi 2.0. This involved eighteen seamstresses who made a total of ninety parkas. The money from these sales was again given to ITK. Gavin Thompson, a vice-president for Canada Goose, told CBC that the brand plans to keep expanding the project. A parka from the first collection was shown at the Inuk Style exhibition in 2020. In 2022, Victoria Kakuktinniq designed a special collection for the third version of Project Atigi. The ads for this collection featured Inuit women as models: throat singer Shina Novalinga, actress Marika Sila, and model Willow Allen.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |