History of Poland (1939–1945) facts for kids

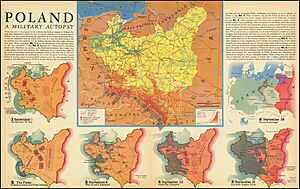

The history of Poland from 1939 to 1945 covers the time from the start of World War II until its end. In September 1939, both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland. They divided and took over the entire country. Later, when Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Germany occupied all of Poland. During this time, Germany carried out terrible policies, including the mass murder of many people.

Millions of Polish citizens suffered greatly under these occupations. About 5.6 million Poles died because of the German occupation, and around 150,000 died under Soviet rule. The Germans especially targeted Jewish people for complete destruction. About 90% of Polish Jews, nearly three million people, were murdered in the Holocaust. Many people, including Jews, Poles, and Romani people, were killed in Nazi death camps like Auschwitz and Treblinka.

The Polish government and military leaders went into exile, first in France, then in Britain. Polish armed forces were rebuilt and fought alongside the Allies in the West. Inside Poland, a strong resistance movement formed, known as the Home Army. This underground group was secretly directed by the Polish Government-in-Exile. There were also other resistance groups, including peasant, right-wing, leftist, and Jewish fighters. Sadly, major uprisings against the Germans, like the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising, were crushed.

Later in the war, the Soviet Union became a key player. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin worked to create a new Polish government that would be friendly to the Soviets. The future of Poland was decided by the major Allied powers (the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union) at conferences like Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam. The Soviet Union kept the eastern part of pre-war Poland. In return, Poland received land from Germany in the west, shifting the country's borders significantly.

Contents

Before the War: Rising Tensions

Poland's Preparation and German Expansion

After 1935, Poland's leaders tried to make their army stronger. They built new factories to produce modern weapons. However, Poland still lagged behind its powerful neighbors, especially Germany.

Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler, Germany's leader, began to rebuild Germany's military, which was against the rules set after World War I. Germany also started taking over nearby lands. In 1938, Germany took over Austria. Poland also took a small border area from Czechoslovakia, hoping to get back land it felt was its own. This action was not well-received by other countries.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

In March 1939, Germany took over the rest of Czechoslovakia. Hitler then demanded that Poland give up the city of Danzig and allow a special highway through Polish land to connect parts of Germany. Poland refused these demands. Britain then promised to help Poland if Germany attacked. Hitler reacted by canceling his non-aggression pact with Poland.

In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a secret agreement called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. This pact was a non-aggression treaty, meaning they promised not to attack each other. But it also had secret parts that planned to divide Eastern Europe, including Poland, between them. This meant Poland's fate was sealed without its knowledge.

Alliances and Warnings

The Soviet Union had offered to form an alliance with France and Britain to stop Germany. However, Poland refused to let Soviet troops enter its territory, fearing they would never leave. Polish leaders believed that working with the Soviets was as dangerous as working with the Germans.

Polish mathematicians had secretly broken Germany's Enigma code machine. They shared this important discovery with Britain and France before the war. This helped the Allies understand German secret messages throughout the war.

By the end of August, Poland had updated its alliances with Britain and France. Poland was partly ready for war, but not fully. Britain and France tried to find a peaceful solution until the last minute. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany.

German and Soviet Invasions of Poland

German Invasion

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany attacked Poland without declaring war. They used a fake incident at a border post as an excuse. German forces, which were much stronger in technology and numbers, quickly moved into Poland. The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact protected Germany from a Soviet attack. On September 17, 1939, Soviet troops also invaded Poland. By the end of the month, Germany and the Soviet Union had divided most of Poland between them.

The Polish military was not ready for such a fast attack. Poland was surrounded on three sides by German territories. Even the new Slovak state helped Germany by attacking Poland from the south. The German army used a new tactic called "Blitzkrieg" (lightning war). This involved fast armored divisions and dive bombers. They attacked cities and transportation, killing many civilians. German forces were ordered to be very cruel and murdered many Polish civilians.

Each German army had special security groups that terrorized Polish people. Some Polish citizens of German background were trained to help the invasion. Many Polish civilians were killed by the German army during the September campaign.

Germany used 58 divisions, including 9 armored divisions, against Poland. They had 1.5 million soldiers, 2,600 tanks, and 1,390 warplanes. Poland had about 1.2 million troops, but many lacked modern weapons. They had 3,600 artillery pieces and 600 tanks. Their air force had 422 aircraft, but many were outdated.

Britain and France declared war on Germany on September 3, but they did little to help Poland. The Poles had expected a strong attack from the West, but it did not happen. The Polish government did not fully understand how isolated and hopeless their situation was.

German forces quickly broke through Polish defenses. Crowds of refugees fleeing to the east blocked roads. The Germans surrounded Warsaw by September 9. The biggest battle of the campaign, the Battle of the Bzura, was fought from September 9–21. On September 12, the Allied leaders in France decided that the Polish military campaign was already lost. The Polish leaders did not know this and still hoped for Western help.

Soviet Invasion

From September 3, Germany urged the Soviet Union to attack Poland. The Soviets waited until Poland was clearly defeated by Germany. On September 17, Soviet troops marched into Poland. They claimed they were protecting Belarusian and Ukrainian people. The invasion was coordinated with the German army. Polish forces were ordered not to fight the Soviets, but some clashes did happen. The Soviet forces moved west to the Bug River, taking the area agreed upon in the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

About 13.4 million Polish citizens lived in the areas taken by the Soviet Union. Many Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Jews in these areas welcomed the Soviet army. Britain and France did not strongly protest the Soviet invasion. If not for the Soviet-German pact, Germany would likely have taken all of Poland in 1939.

End of the Campaign

The Nazi-Soviet agreement was finalized on September 28. It set the new border between them, placing Lithuania in the Soviet sphere and moving the border in Poland to the Bug River. The idea of keeping a small independent Polish state was dropped.

The Polish government and military leaders retreated to southeastern Poland and crossed into neutral Romania on September 17. Germany pressured Romania to intern them, preventing them from going to France. However, General Władysław Sikorski, a Polish opposition leader, managed to leave for France.

Resistance continued in many places. Warsaw was heavily bombed and surrendered on September 27. The city suffered great damage and 40,000 civilians were killed. Other battles continued until early October. Some army units immediately began underground resistance. During the September Campaign, the Polish Army lost about 66,000 soldiers to Germany and 7,000 to the Soviet Union. About 400,000 became German prisoners and 230,000 became Soviet prisoners. 80,000 soldiers managed to escape the country. Many Polish Navy ships reached the United Kingdom, and tens of thousands of soldiers escaped through other countries to continue fighting.

Occupation of Poland

German-Occupied Poland

The German occupation caused the most suffering and terror for Poles. The worst event was the Holocaust, the mass murder of Jewish people. About one-sixth of all Polish citizens died during the war. Most civilian deaths were from deliberate German actions. Germany planned not only to take Polish land but also to destroy Polish culture and the Polish nation.

Large parts of western Poland were added directly to Germany. These included lands Germany had lost after World War I, plus other Polish areas. The annexed areas were divided into German administrative units. About 10.6 million people, mostly Poles, lived in these areas.

In some regions, German courts sentenced thousands of Poles to death. Jews were forced out of annexed areas and put into ghettos, like the Warsaw Ghetto. Catholic priests were also targeted, murdered, or sent to concentration camps. Poles faced property confiscation and severe discrimination. About one million Poles were forced out of their homes and replaced by Germans.

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Polish territories previously held by the Soviets were also organized under German rule. Eastern Galicia, for example, became a new district of the General Government.

The remaining part of Poland was called the General Government, with its capital in Kraków. This area was meant to be part of Germany's "living space" in the east. Hans Frank, a Nazi lawyer, was appointed Governor-General. He oversaw the segregation of Jews into ghettos and forced Polish civilians to work in German war industries.

Some Polish institutions, like the police, were kept but supervised by Germans. Political activity was banned, and only basic Polish education was allowed. University professors were sent to concentration camps. Ethnic Poles were meant to be slowly eliminated. Jews, targeted for faster extermination, were forced into ghettos. Many Jews escaped to the Soviet Union, and some were hidden by Polish families.

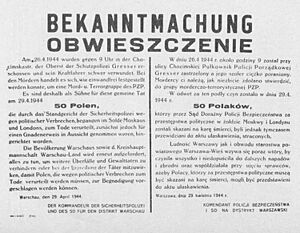

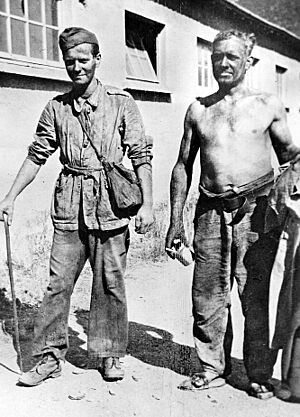

Tens of thousands of Polish intellectuals and others likely to resist were murdered. Catholic clergy were imprisoned or killed. Many resistance members were executed. From 1941, disease and hunger also reduced the population. Poles were deported in large numbers to work as forced labor in Germany. About two million were sent to Germany as slaves, and many died there. Poland was heavily looted and exploited throughout the war.

The Nazis had a plan called "Generalplan Ost" to kill or enslave millions of Slavic people in Eastern Europe. The cleared lands would then be settled by Germans. In 1942–43, they tried this plan in the Zamość region, removing 121,000 Poles from their villages.

Under the "Lebensborn" program, about 200,000 Polish children were kidnapped by Germans. They were tested to see if they looked "German" enough to be Germanized. Only 15-20% of these children were returned to Poland after the war.

When German occupation reached eastern Poland in 1941, the Nazis continued their anti-Jewish policies. They also terrorized ethnic Poles, especially intellectuals and Catholic priests. Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Lithuanians sometimes received better treatment from the Nazis. Their nationalist groups were sometimes used against Poles.

The International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg trials stated that the mass killing of Jews and Poles was genocide. Between 5.62 and 5.82 million Polish citizens died due to the German occupation.

Soviet-Occupied Poland

The Soviet Union took 50.1% of Poland's territory, with about 12.6 million people. This included many Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Jews. The Soviets saw these areas as colonized by Poles and claimed to be liberators. Many minorities welcomed the Red Army.

The Soviets closed Polish state institutions and reopened them with new Soviet leaders. They changed school languages to Ukrainian or Belarusian. All media was controlled by Moscow. The Soviet occupation created a police state based on terror. All Polish parties were banned. Soviet teachers encouraged children to spy on their parents.

The Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic churches were persecuted. Many businesses were taken over by the state. While conditions were difficult, they were generally better than in German-controlled areas. Cities like Lviv and Białystok were well-maintained.

All residents of the annexed areas automatically became Soviet citizens. Those who refused were threatened with being sent to Nazi-controlled Poland. The Soviets used past ethnic tensions to encourage violence against Poles.

The NKVD (Soviet secret police) started a reign of terror. About 230,000 Polish prisoners of war were denied prisoner status. Many officers were secretly executed in the Katyn massacre. Thousands of civilians were arrested and sent to Gulag labor camps in Siberia and Kazakhstan.

Some Poles, like Wanda Wasilewska, cooperated with the Soviets. She was allowed to publish a Polish newspaper. In 1943, the Soviets began forming a new Polish army under Zygmunt Berling to fight alongside them.

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union, many exiled Poles were released from Soviet prisons. Thousands joined the newly formed Polish Army under General Władysław Anders. However, many were too weak to survive the journey.

Around 150,000 Polish citizens died due to the Soviet occupation. About 320,000 were deported.

Cooperation with the Occupiers

In German-occupied Poland, there was no official collaboration at the political or economic level. The Germans wanted to destroy Polish leadership, not work with it. Most people who cooperated with the Nazis were from the German minority in Poland.

Scholars say that only a small number of Poles, perhaps a few thousand out of 35 million, collaborated. The Polish underground courts sentenced about 10,000 Poles for treason, with 200 death sentences.

The Germans forced Polish police to serve the occupation authorities, forming the "Blue Police." Their main job was to handle crime, but they were also used to fight smuggling and patrol Jewish ghettos. Many Blue Police members secretly helped the Polish resistance. However, some also assisted the Nazis in rounding up Poles for forced labor or in actions against Jews.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union, some Polish commanders accepted weapons from the Germans to fight Soviet partisans. This was condemned by the Polish Government-in-Exile. Such cooperation was purely tactical and not based on shared beliefs, unlike collaboration in other countries.

Resistance in Poland

Armed Resistance and the Underground State

The Polish resistance movement was the largest in occupied Europe. Resistance began almost immediately after the invasion. The Service for Poland's Victory was formed on September 27, 1939. This group later became the Union of Armed Struggle, led by General Stefan Rowecki.

The Home Army (Armia Krajowa or AK), loyal to the Government-in-Exile in London, was formed in February 1942. By mid-1944, it had about 400,000 members, but only a small number had enough weapons. The AK carried out many sabotage operations against the Nazis. However, the Nazis often retaliated by killing 100 Polish civilians for every German killed by the resistance.

The Polish Underground State began in April 1940. It was a secret government in Poland, supported by major pre-war political parties. It aimed to continue Polish statehood and carried out political, military, social, and educational activities in secret. In November 1942, Jan Karski, a special envoy, was sent to London and Washington to warn the Allies about the extermination of Jews in Poland.

After Germany Attacked the Soviet Union

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Polish communists became more active. They did not join the main resistance coalition. The Allies also assigned Poland to the Soviet sphere of operations, limiting direct British support for the Polish resistance.

Soviet partisans also became active in Poland, often clashing with the Home Army. This created chaos, as different groups fought each other. With Stalin's encouragement, new Polish communist groups were formed, like the Polish Workers' Party and the State National Council.

Jewish resistance groups, like the Jewish Combat Organization, began armed activities in 1943. In April, the Germans started deporting the remaining Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto, leading to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Jewish leaders knew they would be defeated but preferred to die fighting.

In 1943–44, the Underground State announced its plans for a future Poland. It promised democracy, land reform, and nationalization of industries. The main difference with the communists was about national independence and borders.

Operation Tempest and the Warsaw Uprising

In early 1943, the Home Army prepared for a national uprising. The situation was complicated by the advancing Soviet army, which had different plans for Poland's future. The plan for the uprising was called Operation Tempest. It included major actions like the Warsaw Uprising. In most cases, the Soviets did not cooperate with the Home Army and imposed their own rule.

As Soviet forces neared Warsaw in the summer of 1944, the Home Army launched the Warsaw Uprising on August 1. They hoped to free the capital before the Soviets arrived and establish an independent Polish government. The uprising was planned to last only a few days due to limited supplies.

However, the Germans were still very strong. The Soviets, who were not consulted, gave little help. Stalin had no interest in the uprising's success and waited for the Germans to crush the Polish fighters. The Poles appealed to the Western Allies for help, but little could be done without Soviet involvement.

In Warsaw, the Home Army initially took control of large parts of the city. But they faced a strong German force. The Germans and their allies committed mass killings of civilians. After the uprising surrendered on October 2, the Home Army fighters were treated as prisoners of war. But civilians were punished and evacuated.

The uprising caused at least 150,000 civilian deaths and destroyed most of Warsaw. The Germans systematically looted the city. The defeat of the Warsaw Uprising greatly weakened the Polish resistance. This allowed the Soviets and communists to establish a communist government in Poland with less opposition. The Soviets and their allied Polish army entered Warsaw on January 17, 1945. The Home Army was officially disbanded on January 19.

Government-in-Exile, Communist Victory

Polish Government in France and Britain

A new Polish Government-in-Exile was formed in Paris on September 30, 1939. Władysław Raczkiewicz became president, and General Władysław Sikorski became prime minister and commander-in-chief. The government wanted to restore Poland's pre-1939 borders and gain land from Germany.

By spring 1940, an 82,000-strong Polish army was formed in France. Polish soldiers fought in Norway and defended France against the German invasion. After France was defeated, the Polish government and about 19,000 soldiers were evacuated to Britain.

Polish pilots became famous for their bravery during the Battle of Britain. Polish sailors served with distinction in the Battle of the Atlantic. Polish soldiers also fought in North Africa.

Polish Army's Evacuation from the Soviet Union

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, Britain allied with the Soviets. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill urged Sikorski to also make an agreement with the Soviets. The Sikorski–Mayski treaty was signed on July 30, restoring Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations. Polish soldiers and others imprisoned in the Soviet Union since 1939 were released. It was agreed to form a Polish army in the Soviet Union to fight Germany.

Sikorski visited Stalin in the Soviet Union. They agreed to move the Polish army, led by General Władysław Anders, to the Middle East. About 78,000 Polish soldiers and tens of thousands of civilians left the Soviet Union for Iran in 1942. Most of these soldiers formed the II Corps, which later fought bravely in Italy, including at the Battle of Monte Cassino.

Decline of the Government-in-Exile

As Soviet forces advanced westward, it became clear that Stalin's plans for Poland were different from those of the Polish Government-in-Exile. Polish-Soviet relations worsened. New Polish communist groups were formed in Poland and the Soviet Union.

In April 1943, the Germans discovered mass graves of Polish officers at Katyn, near Smolensk. The Polish government suspected the Soviets were responsible and asked the Red Cross to investigate. The Soviets denied it, and Stalin reacted by cutting diplomatic ties with the Polish Government-in-Exile.

Prime Minister Sikorski was killed in an air crash in July 1943. His death further weakened the Polish government's position among the Allies.

At the Tehran Conference in late 1943, Allied leaders (Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin) agreed that Poland's new eastern border would be the Curzon Line. They also agreed to compensate Poland with land from Germany. The Poles were not consulted about these decisions.

As the Red Army entered Poland in 1944, Stalin demanded that the Polish Government-in-Exile recognize the new borders and remove leaders he considered "hostile." The Polish government in London lost its influence.

In June 1944, Polish Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk visited President Roosevelt, who urged him to talk directly with Stalin. Mikołajczyk later resigned because he could not convince his government to accept the territorial compromises. The British and Americans were then unwilling to deal with the Polish government that followed.

In 1944, Polish forces in the West made major contributions to the war. The II Corps stormed Monte Cassino in Italy. General Stanisław Maczek's 1st Armoured Division fought bravely in France and Belgium. General Stanisław Sosabowski's Parachute Brigade fought at Arnhem. The Polish Air Force and Navy also played important roles.

Soviet and Polish-Communist Victory

Soviet and allied Polish armies crossed the Bug River in July 1944. As they approached Warsaw, the Warsaw Uprising began. The Soviets paused their advance, allowing the Germans to crush the uprising. This opened the way for communist rule in Poland. The Soviets arrested and deported members of the Home Army and Underground State.

In January 1945, Soviet and Polish armies launched a massive offensive to liberate Poland and defeat Germany. Kraków was liberated on January 18. Auschwitz concentration camp survivors were freed on January 27. The Polish First Army entered the ruins of Warsaw on January 17, formally liberating the city.

The Polish Army, which grew to 400,000 soldiers, fought alongside the Soviets all the way to Berlin. Over 600,000 Soviet soldiers died fighting in Poland. Many Germans fled westward, terrified by reports of Soviet actions. By the end of the war, the Polish armed forces were the fourth largest on the Allied side.

Poland Reestablished with New Borders

Poland's War Losses

The human cost of World War II for Poland was immense. About 644,000 Polish citizens died from military action, and 5.1 million died from the occupiers' terror and extermination policies. Most of these deaths were civilians.

About 90% of Polish Jews died. Most who survived did so by fleeing to the Soviet Union. After the war, many surviving Jews left Poland due to anti-Jewish violence and a desire to start new lives elsewhere.

Among ethnic Poles, those with higher education suffered the most. About a third or more did not survive. Only about 10% of Poland's human losses were from military action; the rest were from intentional killings and hardships of war.

The war destroyed 38% of Poland's national wealth. Most of its factories and farms were ruined. Warsaw and other cities were largely destroyed and needed massive rebuilding.

| Specification | Number of persons in thousands | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Loss of life — total

a) due to direct military action |

6.028 644 |

100.0 10.7 |

| 2. War invalidity (war invalids and civilian invalids — total) a) physical handicap |

590 530 |

100.0 89.8 |

| 3. Excess of tuberculosis instances (exceeding the average theoretical number of instances) | 1.140 | 100.0 |

Beginnings of Communist Government

The State National Council (KRN), led by Bolesław Bierut, was formed in Warsaw by the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) on January 1, 1944. As the Soviets advanced, the communist-controlled Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) was set up in Lublin in July 1944. This group began to take over the country's administration. The PKWN issued a manifesto on July 22, starting an important land reform.

The communists were a small but powerful group. They worked with other Polish politicians who believed Soviet control was unavoidable. These groups formed the new Polish administration, ignoring the existing Underground State.

The Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland was formed in Lublin at the end of 1944. It was recognized by the Soviet Union and other countries. In April 1945, this government signed an alliance with the Soviet Union.

Allied Decisions and New Government

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Allies finalized decisions on Europe's post-war order. Churchill and Roosevelt accepted the Curzon Line as Poland's eastern border. They also agreed to give Poland land from Germany in the west. Poland was to have a temporary government of national unity, including both the existing communist government and pro-Western forces. The Polish Government-in-Exile protested these decisions.

Former Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk eventually accepted the Yalta decisions. In June 1945, he and other Polish democrats agreed with Stalin to form a Government of National Unity. This government was established on June 28, 1945, with Edward Osóbka-Morawski as prime minister and Władysław Gomułka and Mikołajczyk as deputy prime ministers. It was quickly recognized by the United Kingdom, the United States, and most other countries. Although formally a coalition, the government was controlled by the Polish Workers' Party. The exile government in London remained in existence but was no longer recognized.

Persecution of Opposition

The new communist authorities, backed by the Soviet NKVD and the Red Army, began to persecute political opponents. Many were arrested and executed. Thousands died in labor camps created by the Soviets.

Leaders of the Polish Underground State were invited to talks with the NKVD in March 1945. They were all arrested and taken to Moscow for trial. The British and Americans protested but could not secure their release. In June 1945, the "Trial of the Sixteen" took place in Moscow.

After the war, the Soviets looted German industrial property in Poland as war reparations. As the Soviets and pro-Soviet Poles took control, they faced armed resistance from former underground members and nationalist groups. Thousands of people were killed in this conflict.

A "Democratic Bloc" was formed by the communists and their allies. Mikołajczyk's Polish People's Party (PSL) was the only legal opposition. Other Polish political movements were not allowed to exist. Many Poles and some Western historians criticized the Western Allies for "abandoning" Poland to Soviet rule.

Soviet-Controlled Polish State

Post-war Poland became a state with limited independence, heavily influenced by the Soviet Union. This was the only possible outcome given the circumstances. The cooperation of the Polish Left with Stalin's regime helped preserve a Polish state within favorable borders.

As agreed at Yalta, the Soviet Union kept the eastern lands of Poland. In return, Poland received German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line, including parts of Pomerania, Silesia, and East Prussia. Millions of Germans were expelled from these new Polish territories.

The new western and northern territories of Poland were resettled by Poles who were "repatriated" from the eastern regions now in the Soviet Union. Ukrainians and Belarusians were also moved from Poland to their respective Soviet republics. This ensured that post-war Poland would not have large minority groups. Poland's territory became 20% smaller than in 1939.

Poland's new western borders were questioned by Germany and some Western countries. The Soviet Union guaranteed these borders, which further increased Poland's dependence on the Soviets.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Polonia (1939-1945) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Polonia (1939-1945) para niños

- History of Poland (1945–1989)

- List of Polish cities damaged in World War II

- Polish culture during World War II

- Polish material losses during World War II

- World War II casualties of Poland