History of Poland (1945–1989) facts for kids

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 covers the time when Poland was a communist country after World War II. During these years, Poland saw a lot of industrial growth and cities grew bigger. People's lives generally got better. However, this period also had tough times. There were early Stalinist controls, social problems, political fights, and money troubles.

As World War II ended, the Soviet Red Army and Polish forces pushed out the German army from Poland. In February 1945, a meeting called the Yalta Conference decided that Poland would have a temporary government. This government was a mix of groups until elections could be held. But Joseph Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, made sure the communists had control. A government called the Provisional Government of National Unity was set up in Warsaw. It ignored the Polish government-in-exile that had been in London since 1940.

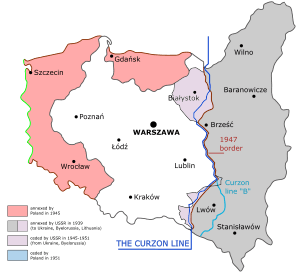

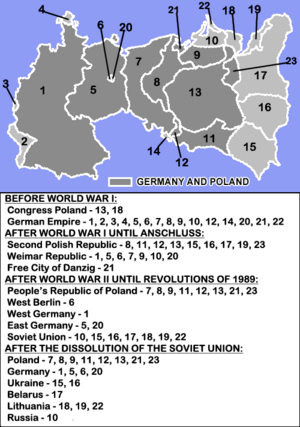

Later, at the Potsdam Conference in July–August 1945, the main Allied countries agreed to move Poland's borders far to the west. Poland's new territory was between the Oder–Neisse line and the Curzon Line. This made Poland smaller than before the war. After the war, Poland became a country with mostly one ethnic group. This happened because many Jewish people were killed in the Holocaust. Also, many Germans left or were moved out, and Ukrainians and Poles were resettled.

The new government soon gained strong political power. The Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR), led by Bolesław Bierut, took firm control. Poland remained an independent country but was part of the Eastern Bloc, under Soviet influence. The July Constitution was put into law on 22 July 1952. The country was then officially named the Polish People's Republic (PRL).

After Stalin died in 1953, things became a bit more open. This "thaw" allowed a more liberal group of Polish communists, led by Władysław Gomułka, to take power. By the mid-1960s, Poland faced more money and political problems. These problems led to the 1968 Polish political crisis and the 1970 Polish protests. When food prices went up, many workers went on strike. The government then started a new economic plan. It involved taking large loans from Western countries. This led to a rise in living standards and hopes. But the plan also connected Poland's economy more to the world economy. It struggled after the 1973 oil crisis. In 1976, the government of Edward Gierek had to raise prices again. This caused the June 1976 protests.

The cycle of strict rules and reforms changed when Karol Wojtyła was elected Pope John Paul II in 1978. His election gave a big boost to those who opposed the government. This was especially true during the pope's first visit to Poland in 1979. In August 1980, a new wave of strikes began. This led to the creation of the independent trade union "Solidarity" (Solidarność). It was led by Lech Wałęsa. The growing strength of the opposition made the government of Wojciech Jaruzelski declare martial law in December 1981. However, with changes happening in the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev, more pressure from the West, and a struggling economy, the government had to talk with its opponents. The 1989 Round Table Talks led to Solidarity taking part in the 1989 election. Their big win started the first of many changes from communist rule in Central and Eastern Europe. In 1990, Jaruzelski stepped down as president. Wałęsa became president after the presidential election.

Contents

Poland After World War II (1944–1948)

Changes to Borders and People

Before World War II, about one-third of Poland's people were from ethnic minorities. In 1939, Poland had about 35 million people. But by 1946, fewer than 24 million lived within its new borders. Of these, over three million were minorities like Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews. Most of them soon left Poland.

Poland lost the highest percentage of its people in World War II. About 16–17 percent of its population died. Around 6 million Polish citizens died from war-related causes between 1939 and 1945. This includes 3 million Polish Jews. About 2 million ethnic Poles also died.

The war greatly affected Poland's historical minorities. The country's many different ethnic groups, seen in past counts, mostly disappeared a few years after the war. Many educated Poles also suffered greatly. Many of the country's leaders and thinkers from before the war died or were scattered.

Rebuilding Poland was hard. The new government struggled to gain full control. There was also much mistrust of the new leaders. Poland's new borders were not set until mid-1945. Soviet forces took valuable industrial equipment and factories from the former eastern territories of Germany that were given to Poland. They sent these assets to Russia.

After the Soviets took the Kresy lands east of the Curzon Line, about 2 million Poles were moved to the new western and northern lands. These lands were taken from Germany and given to Poland under the Potsdam Agreement. Other Poles stayed in what became the Soviet Union. More moved to Poland after 1956. With people from central Poland also moving, the number of Poles in these new "Recovered Territories" reached 5 million by 1950. Most of the 10 million former German residents had fled or were expelled to post-war Germany by 1950. This included about 4.4 million during the war and 3.5 million moved by Polish officials in 1945–1949. The Allies decided on the expulsion of Germans at Potsdam.

Poles also moved Ukrainians and Belarusians from Poland to the Soviet Union. In 1947, Operation Vistula spread out the remaining Ukrainians in Poland. Most Polish Jews were killed by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust. Many survivors moved to the West and to the new country of Israel. For the first time, Poland became a country with mostly one ethnic group. These forced and voluntary moves were some of the biggest population changes in European history.

Unlike other European countries, Poland continued to try Nazi criminals and their helpers into the 1950s. Poland was very strict in looking into and prosecuting war crimes among the communist nations after the war. Between 1944 and 1985, Polish courts tried over 20,000 people, including 5,450 Germans.

Rebuilding Cities and the Economy

Poland's buildings and roads were badly damaged during the war. This made it fall even further behind Western countries in making goods. Over 30% of Poland's pre-war resources and buildings were lost. Poland's capital, Warsaw, was one of the most destroyed cities. Over 80 percent was ruined after the Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

Poland gained more developed western lands and lost its poorer eastern regions. By 1948, Poland's industrial production was higher than before the war. This happened during the Three-Year Plan. People worked hard to rebuild their lives. The Three-Year Plan was created by the Central Planning Office. It was led by Czesław Bobrowski and economist Hilary Minc. They wanted to keep some parts of a market economy. People's living standards in Poland got much better. But Soviet pressure made the Polish government reject the American Marshall Plan in 1947. Instead, Poland joined the Soviet-led Comecon in 1949.

Warsaw and other ruined cities were quickly rebuilt. People cleared the rubble, mostly by hand. Materials often came from former German cities like Wrocław. Wrocław, Gdańsk, Szczecin, and other formerly German cities were also completely rebuilt.

Communist Power Takes Hold

The Soviet Union wanted to make sure Poland would be under its influence. So, before the Red Army even entered Poland, it tried to remove any pro-Western groups. In 1943, after the Katyn massacre was revealed, Stalin stopped talking to the Polish government-in-exile in London. At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union agreed to allow a government with communists and pro-Western Poles. They also agreed to hold free elections later.

The old Communist Party of Poland was destroyed in Stalin's purges in 1938. About five thousand Polish communists were sent to Russia and killed. But in 1941, some survivors convinced the Soviets to restart a Polish party. This new party, the Polish Workers' Party (PPR), started in Warsaw in January 1942. After its first leaders died or were arrested, Władysław Gomułka became its first secretary by late 1943. Gomułka was a strong communist. He disliked Soviet ways but believed Poland needed to be friends with the Soviet Union. He may have survived the purges because he was in prison in Poland in 1938–39.

Gomułka stayed in Poland during the German occupation. He was not part of the group Stalin organized in the Soviet Union. In 1945, Gomułka's party was small compared to other groups in Poland.

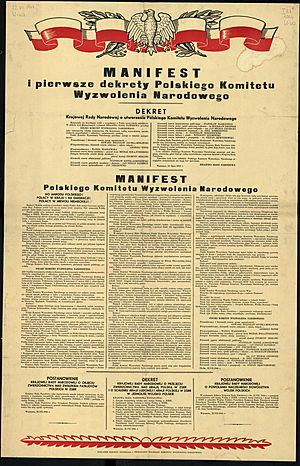

When Polish lands were freed, control went from Nazi Germany to the Red Army. Then it went to Polish communists. They formed the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) in July 1944 in Lublin. Polish communists became the most powerful group in Poland, even though they had little support at first. The PKWN said it followed the old March Constitution of Poland.

On 6 September 1944, the PKWN announced a big land reform. This changed the old social and economic structure of the country. Over one million peasant families received land from large estates.

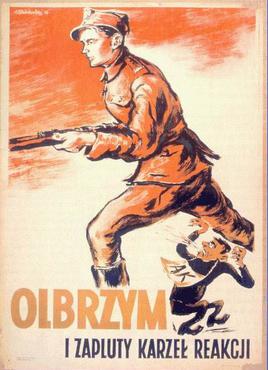

The communists were helped by the Yalta decisions and Soviet support. They controlled important government parts, like the security services. After the Warsaw Uprising was defeated in late 1944, the exiled government from London was seen as failing. Its groups became isolated. Resistance against communist forces weakened. People were tired of years of hardship. They found the ideas of the PKWN Manifesto more appealing. Besides land reform, the PKWN Manifesto did not call for other big changes in ownership. It did not mention taking over industries. Businesses were supposed to go back to their owners. Workers in freed areas started taking over factories in 1944. They set up workers' councils and began rebuilding and producing. The PPR had to use much effort to take control of these factories.

The PKWN became the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland in January 1945. This government was led by Edward Osóbka-Morawski, a socialist. But communists held most key positions. A Polish-Soviet friendship treaty in April 1945 limited Western influence in Poland. Later Soviet-influenced governments answered to the State National Council (KRN). This was a communist-controlled parliament formed by Gomułka in January 1944. The Polish government-in-exile did not recognize these communist structures. It formed its own parliament, the Council of National Unity (RJN).

The Yalta agreement said Poland's government should include "all democratic and anti-Nazi elements." Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk of the Polish government-in-exile resigned in November 1944. He accepted the Yalta terms and went to Moscow. He talked with Bolesław Bierut about forming a "national unity" government. Mikołajczyk and other exiled Polish leaders returned to Poland in July 1945.

The new Provisional Government of National Unity (TRJN) was set up on 28 June 1945. It lasted until the elections of 1947. Edward Osóbka-Morawski remained prime minister. Gomułka became first deputy prime minister, and Mikołajczyk became second deputy and minister of agriculture. The government was "provisional." The Potsdam Conference soon said that free elections must be held.

The communists' main rivals were former members of the Polish Underground State. These included Mikołajczyk's Polish People's Party (PSL) and soldiers from the Polish Armed Forces in the West. Mikołajczyk's party was important because the communists legally recognized it. It could work in Polish politics. The PSL wanted to stop the communists from having all the power. It also hoped to create a parliament and a market economy by winning the promised elections. Mikołajczyk hoped an independent Poland, friendly with the Soviet Union, could be a bridge between East and West.

Soviet-backed parties controlled most of the power. This was especially true for the Polish Workers' Party under Gomułka and Bierut. Bierut represented those who came from the Soviet Union to join the Polish party. This increased after the PPR Congress in December 1945. The party's members grew from a few thousand in early 1945 to over one million in 1948.

To show Soviet control, sixteen important leaders of the Polish anti-Nazi underground were put on trial in Moscow in June 1945. Their removal meant that a democratic change, as called for by the Yalta agreements, was not possible. British and American diplomats watched the trial without protest. The exiled government in London, led by Tomasz Arciszewski after Mikołajczyk's resignation, was no longer officially recognized by Great Britain and the United States on 5 July 1945.

From 1945–47, about 500,000 Soviet soldiers were in Poland. Between 1945 and 1948, Soviet authorities imprisoned about 150,000 Poles. Many former Home Army members were caught and killed. At a PPR meeting in May 1945, Gomułka said Poles saw communists as "the NKVD's worst agency." Edward Ochab said Soviet troops leaving Poland was a top goal. But tens of thousands of Poles died in the post-war struggles. Many were sentenced on false charges or sent to the Soviet Union. Soviet troops' status in Poland was not made legal until late 1956. This happened when a Polish-Soviet agreement was signed. The Soviet Northern Group of Forces would stay in Poland.

Fake Elections, Mikołajczyk's Defeat

Stalin had promised free elections in Poland at the Yalta Conference. However, Polish communists, led by Gomułka and Bierut, did not plan to give up power. They knew they had little support from the people. To get around this, in 1946, a national vote called the "Three Times Yes" referendum was held before the parliamentary elections. The referendum asked three general but political questions about the Senate, national industries, and western borders. It was meant to check and boost the popularity of communist ideas. Most important parties were left or center. They could have easily approved all three options. But Mikołajczyk's Polish People's Party (PSL) decided to oppose the first question: ending the Senate. The communists voted "Three Times Yes."

Partial results, put together by the PSL, showed little support for the communist side on the first question. But after a campaign with fake votes and threats, the communists claimed big wins on all three questions. This led to the nationalization of industry and state control of the economy. It also created a single national parliament (Sejm).

The communists gained power by slowly taking away the rights of their non-communist enemies. They especially crushed Mikołajczyk's PSL party. In some well-known cases, perceived enemies were sentenced to death on false charges. One was Witold Pilecki, who organized resistance in Auschwitz. Leaders of the Home Army and the Council of National Unity were also persecuted. Many resistance fighters were killed or forced to leave the country. Opposition members were also harassed by the government. The Ministry of Public Security (UB), NKVD, and Red Army steadily reduced the number of partisans. The right-wing uprising greatly decreased after the amnesty of July 1945 and faded after the amnesty of February 1947.

By 1946, all right-wing parties were banned. A new pro-government Democratic Bloc was formed in 1947. It included only the Polish Workers' Party and its allies. On 19 January 1947, the first parliamentary elections took place. They mainly featured the PPR and allied candidates. Mikołajczyk's Polish People's Party was the main opposition. However, the PSL's power was already weakened by government control and persecution. Stalin adjusted the election results to favor the communists. Their bloc claimed 80% of the votes. The British and American governments protested the election. They said it clearly broke the Yalta and Potsdam agreements. The rigged elections ended the multi-party system in Poland. This time, the vote fraud was much better hidden. An NKVD colonel in charge of election oversight told Stalin that about 50% of the votes were for the regime's Democratic Bloc. In the new Sejm, out of 444 seats, 27 went to Mikołajczyk's party. Mikołajczyk said the results were fake. He was threatened with arrest and fled the country in October 1947, helped by the US Embassy. Other opposition leaders also left. In February, the new Sejm created the Small Constitution of 1947. Over the next two years, the communists took all political power in Poland.

Polish United Workers' Party and Its Rule

The old Polish Socialist Party (PPS) split at this time. The ruling Stalinists used "salami tactics" to break up the opposition. Communist politicians worked with the left-wing PPS group led by Józef Cyrankiewicz. He became prime minister under new president Bierut in February 1947. The socialists' choice to work with the communists led to their party's end. Cyrankiewicz visited Stalin in Moscow in March 1948 to talk about joining parties. The Kremlin was not happy with Gomułka leading the communist party. They agreed to the merger. Cyrankiewicz secured his own place in Polish politics until 1972. In December 1948, Gomułka was removed. Bierut was put in charge of the communist Polish Workers' Party. The PPR and Cyrankiewicz's PPS joined to form the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR). This party held power for the next forty years. Poland became a one-party state and a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Only two other parties were allowed: the United People's Party (ZSL), which came from Mikołajczyk's PSL and represented farmers, and the Alliance of Democrats (SD), a small party for educated people.

As the time of Sovietization and Stalinism began, the PZPR was not united. The biggest split happened before the union with the PPS. Stalinists forced Gomułka out of the PPR's top job. They suppressed his group of native communists. The PZPR split into several groups. They had different ideas and ways of doing things. They also wanted different levels of independence from the Soviet Union. While Marxism–Leninism was the official idea, the communist government continued many old Polish ways. This included methods from past Polish rulers and traditions of working with the countries that had divided Poland in the 19th century.

Poland was part of the Soviet Bloc. The party's goals of power and reform were always limited. This was due to rules from the Soviet Union and the Polish people's unhappiness. Poles knew they lacked national independence and freedoms. Party leaders also knew they would lose their jobs if they did not follow Soviet rules. Poland's political history was shaped by the Soviets and Polish communists needing each other.

A political elite called the nomenklatura grew. It included leaders, managers, and officials in the ruling party. They were in all parts of government and other organizations. Nomenklatura members were chosen by the party. They controlled all public life, like the economy, industry, and education. The party said this group ensured that reliable and skilled people were in charge. But later, critics like Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski said this system was a dictatorship by central officials for their own benefit. The Polish public generally liked the government's social programs. These included building apartments, child care, worker vacations, health care, and full employment. But people disliked the special privileges given to nomenklatura members and security services.

Stalinist Era (1948–1956)

Gomułka Removed, Stalinist Controls

After 1948, Poland, like other Eastern Bloc countries, had a Soviet-style purge. Communist officials were accused of "nationalist" or "deviationist" ideas. This campaign included the arrest of Marian Spychalski in May 1950 and Michał Rola-Żymierski five months after Stalin died. In September 1948, Władysław Gomułka and other communist leaders who stayed in Poland during the war were accused of not following Leninism. They were removed from the party for opposing Stalin's direct control. Gomułka was accused of "right-wing nationalist deviations." He had indeed focused on Polish socialist traditions. He also criticized Rosa Luxemburg's party for downplaying Polish national goals. More seriously, the Soviets claimed Gomułka was part of an anti-Soviet plot. He was arrested by the Ministry of Public Security (MBP) in August 1951. He was questioned by Roman Romkowski and Anatol Fejgin, as the Soviets demanded. Gomułka was imprisoned without a public trial and released in December 1954. Bierut replaced Gomułka as leader of the PPR (and then the PZPR). Gomułka's Polish friends and his past defiance helped him in 1956. That's when the Polish party had a chance to become more independent.

Polish communists who came from wartime groups in the Soviet Union, like the Union of Polish Patriots, controlled the Stalinist government. Their leaders included Wanda Wasilewska and Zygmunt Berling. Now in Poland, those still active and favored by Russia ruled the country. They were helped by the MBP and Soviet "advisers" in every part of the government. These advisers ensured pro-Soviet policies. The most important was Konstantin Rokossovsky, Poland's defense minister from 1949 to 1956. He was a Soviet Marshal and war hero.

Military service became required again after the war. The army soon reached its size of 400,000 men.

Soviet-style secret police, including the Department of Security (UB), grew to about 32,000 agents by 1953. At their peak, there was one UB agent for every 800 Polish citizens. The MBP also controlled the Internal Security Corps, the Civil Militia (MO), border guards, prison staff, and paramilitary police ORMO. The ORMO started as a self-defense group. In February 1946, the PPR organized this group.

During Stalin's time, prosecutors, judges, and officials of the Ministry of Public Security committed acts that are considered crimes against humanity. For example, in 1951, members of the Freedom and Independence (WiN) group were executed in Warsaw. These were former anti-Nazi fighters who had come forward after an official amnesty. The post-war Polish Army, intelligence, and police had Soviet NKVD officers. These officers stayed in Poland until 1956.

Many people were arrested in the early 1950s. In October 1950, 5,000 people were arrested in one night. In 1952, over 21,000 people were arrested. By late 1952, official data showed Poland had 49,500 political prisoners. Former Home Army commander Emil August Fieldorf suffered years of harsh treatment in the Soviet Union and Poland. He was executed in February 1953, just before Stalin died.

Many people, including some in the PZPR, resisted the Soviet and local Stalinists. This limited the harm from the harsh system in Poland. Political violence after 1947 was not widespread. The Church, though some of its property was taken, remained mostly untouched. Educated people kept their ability to bring about future reforms. Farmers avoided full collectivization. Some private businesses survived. Changes slowly happened between Stalin's death in 1953 and the Polish October of 1956.

Nationalization and Planned Economy

In February 1948, Minister of Industry Hilary Minc attacked the Central Planning Office. He called it a "bourgeois" leftover. The office was closed. The Polish Stalinist economy began. The government of President Bierut, Prime Minister Cyrankiewicz, and Minc started big economic changes. Poland became like the Soviet model of a "people's republic." It had a centrally planned command economy. This was different from the earlier appearance of democracy and partial market economy.

Ownership of industry, banks, and rural land changed greatly. These changes were made in the name of egalitarianism (equality). They had wide public support.

The way Poland's economy worked was set up in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Soviet-style planning began in 1950 with the Six-Year Plan. It focused on quickly building heavy industry. This "accelerated industrialization" happened after the Korean War started. It was driven by Soviet military needs. Many consumer-focused investments were canceled. The plan also tried to force collectivization of agriculture, but this failed.

One main project was the Lenin Steelworks and its "socialist city" of Nowa Huta (New Steel Mill). Both were built from scratch in the early 1950s near Kraków. Land taken from large landowners was given to poorer farmers. But later attempts to take land from farmers for collectivization were widely disliked. In what was called the "battle for trade," private businesses were taken over by the state. Within a few years, most private shops disappeared. The government started a campaign to collectivize farms. But this was slower than in other Soviet countries. Poland remained the only Eastern Bloc country where individual farmers still owned most of the land. A Soviet-Polish trade treaty in January 1948 set the main direction for Poland's future trade.

In 1948, the United States announced the Marshall Plan. This plan aimed to help rebuild post-war Europe. After first welcoming the idea, the Polish government refused American help. This was due to pressure from Moscow. After the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, the Soviet Union forced Poland to give up its claims for money from Germany. As a result, Germany paid no major war damages to Poland or its citizens. Poland's compensation came from the land and property left by Germans in the annexed western territories.

Despite no American aid, East European "command economies," including Poland, made progress. They closed the historical wealth gap with Western Europe's market economies. Capital accumulation made Poland's national income grow over 76% in real terms. Farm and factory production more than doubled between 1947 and 1950. Big social changes helped the economy and industry grow. Farmers moved to cities and became workers (1.8 million between 1946 and 1955). Cities grew quickly. The total population of Polish cities increased by 3.1 million. Cheap labor and access to the Soviet market helped gather resources. But productivity was low, and there was not enough investment in new technologies. The centrally planned economies of Eastern Europe grew relatively better than the West in the post-war years. But they suffered economic damage later, especially after the 1973 oil crisis. However, the rise in living standards was not as good as in the West.

Reforms and De-Stalinization

The last Polish–Soviet land exchange happened in 1951. About 480 square kilometers of land along the border were swapped between Poland and the Soviet Union.

The Constitution of the Polish People's Republic was put into law in July 1952. The country officially became the Polish People's Republic (PRL). It promised free health care for everyone. Large state-owned enterprises gave employees many benefits. These included housing, sports places, and hospitals. These benefits started to shrink in the 1970s. In the early 1950s, the Stalinist government also made big changes to the education system. The program of free and required schooling for all, and free higher education, was very popular. But communists controlled what was taught. History and other subjects had to follow Marxist ideas approved by ideological censorship. From 1951–53, many pre-war professors seen as against the government were fired from universities. Government control over art and artists grew. Soviet-style socialist realism became the only accepted art form after 1949. Most art and literature served as party propaganda.

The reforms often helped many people. After World War II, many were willing to accept communist rule for a return to normal life. Hundreds of thousands joined the communist party. But many Poles still felt unhappy. They adopted a "resigned cooperation" attitude. Others, like the Freedom and Independence group (from the Home Army) and the National Armed Forces, actively fought the communists. They hoped for a World War III to free Poland. Most people who fought the communist government gave up during amnesties in 1945 and 1947. But the secret police continued harsh actions. Some fought into the 1950s.

The communists angered many Poles by persecuting the Catholic Church. The PAX Association, created in 1947, tried to divide Catholics and promote a church friendly to communist rule. PAX did not succeed much in changing Catholic public opinion. But it published many books and approved Catholic newspapers. In 1953, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, the Primate of Poland, was put under house arrest. This happened even though he was willing to compromise with the government. In the early 1950s, the war against religion by the secret police led to arrests of hundreds of religious people. This ended with the Stalinist show trial of the Kraków Curia.

The 1952 constitution promised many democratic rights. But in reality, the Polish United Workers' Party controlled the country. It used its own rules to oversee all government bodies.

Stalin died in 1953. This led to a partial thaw in Poland. Nikita Khrushchev became the new Soviet leader. The PZPR's Second Congress met in March 1954. Cyrankiewicz, who had been replaced as prime minister by Bierut, returned to that post. He remained prime minister until December 1970. The Six-Year Plan was changed to make more goods for people. Khrushchev, at the Congress, asked Bierut why Gomułka was still held. Bierut denied knowing.

After an official, Józef Światło, left to the West and revealed secrets, the Ministry of Public Security was closed in December 1954. Gomułka and his friends were freed. Censorship was slightly relaxed. Two notable magazines, Po prostu and Nowa Kultura, dared to speak out. From early 1955, the Polish press criticized the Stalinist past. It praised older Polish socialist traditions. Political discussion groups grew. The party itself seemed to be moving towards social democracy. Leftist thinkers, who joined the party for social justice, moved more decisively towards social democracy. They soon started the Polish revisionism movement.

In February 1956, Khrushchev criticized Stalin's cult of personality at a Soviet party meeting. He began a reform course. The de-Stalinization of Soviet ideas put Poland's Stalinist hardliners in a tough spot. Unrest and a desire for reform grew across the Eastern Bloc. Stalin's ally Bierut died in March 1956 in Moscow. This made a split in the Polish party worse. In March, Edward Ochab replaced Bierut as first secretary. The Soviet Congress also inspired some democracy in Poland. Ochab started reforms to decentralize industry and improve living standards.

The number of security agents was cut by 22%. A widespread amnesty released 35,000 prisoners. 9,000 political prisoners were freed. Hardline Stalinists like Jakub Berman were removed from power. Some were arrested. Berman was dismissed in May but never prosecuted. A few people who committed Stalinist crimes were tried and jailed. A wider plan to charge those responsible was proposed but not approved by Gomułka. He was a victim of Stalinist persecution himself. Gomułka made some changes but did not want to destabilize the security system, now under his control, by wide-ranging trials.

Gomułka's Time (1956–1970)

Polish October

On 28 June 1956, workers in Poznań went on strike and rioted. They had asked officials many times to help improve their bad situation. The strike started because of wage cuts and changed working conditions. Protests by factory workers became a huge citywide protest. The military brought 16 tanks and other vehicles. Some were taken by protesters, who also broke into government buildings. 57 people died and hundreds were hurt in two days of fighting. Several large military groups arrived. But the army mainly supported the police and security forces. At the Poznań radio station, Prime Minister Cyrankiewicz warned the rioters. He said anyone who "dares raise his hand against the people's rule may be sure that... the authorities will chop off his hand." Of the 746 people arrested, almost 80% were workers. Officials tried to find out if the events were planned by Western or anti-communist groups. They failed. The events were found to be spontaneous and locally supported. The Poznań revolt led to bigger, more liberal changes within the Polish communist party. It also changed its relationship with Moscow.

The protests and violence deeply shook the party. The 7th Plenum of the Central Committee in July 1956 split into two groups. These were the "hardliners" Natolin and the "reformist" Puławy factions. The Natolin group included communist officials from the army and state security. They wanted to remove "Stalin's Jewish protégés" but had Stalinist sympathies themselves. Many in the Puławy group were former Stalinist supporters. They became liberal reformers and wanted Gomułka to return to power. In response to the unrest, the government tried to make peace. Wage increases and other reforms for Poznań workers were announced. In the party and among educated people, demands for wider reforms of the Stalinist system grew stronger.

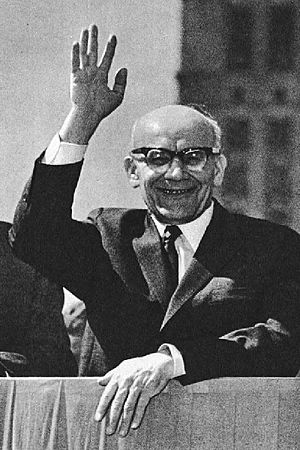

The leaders realized they needed new leadership. In what became known as the Polish October, the Politburo chose Gomułka. He had been freed from prison and brought back into the party. The Central Committee then elected him as the new first secretary of the PZPR without Soviet approval. Gomułka convinced Soviet leaders that he would keep Soviet influence in Poland. Before Gomułka's rise, there were worrying Soviet military moves. A high-level Soviet group led by Khrushchev flew to Warsaw. They wanted to see and influence the changes in the Polish party. After some tense talks, they returned to Moscow. The Soviet leader announced on 21 October that armed intervention in Poland should be dropped. This was supported by pressure from communist China. China demanded that the Soviets leave the new Polish leaders alone. On 21 October in Warsaw, Gomułka returned to power. This started an era of national communism in Poland. Gomułka promised to end Stalinism. In his speech, he spoke of many social democratic reform ideas. This gave hope to left-wing revisionists and others that the communist state could be reformed. The revisionists wanted to represent the worker movement. Their main goals were political freedom and self-management in state businesses. However, the end of Soviet influence in Eastern Europe was not yet in sight. On 14 May 1955, the Warsaw Pact was signed in Warsaw to counter NATO.

Many Soviet officers in the Polish Armed Forces were dismissed. But very few Stalinist officials were put on trial for the harsh actions of the Bierut period. The Puławy group argued that mass trials of Stalinist officials, many of whom were Jewish, would cause hatred towards Jews. Konstantin Rokossovsky and other Soviet advisers were sent home. The Polish communist system became more independent. Gomułka knew about the political situation. He agreed that Soviet troops would stay in Poland. No open anti-Soviet actions would be allowed. However, he made Polish-Soviet relations more formal. A military cooperation treaty in December 1956 said that Soviet forces in Poland "can in no way violate the sovereignty of the Polish state." Poland avoided Soviet armed intervention, unlike the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Gomułka, in turn, supported the Soviets loyally throughout his career. In one act of defiance, the Polish delegation at the United Nations did not vote to condemn the Soviet intervention in Hungary in November 1956.

Some Polish academics and philosophers tried to connect Poland's history with Marxist ideas. They wanted to create a unique form of Polish Marxism. But these efforts were stopped. The government did not want to anger the Soviet Union by straying too far from the Soviet party line. Leszek Kołakowski, a leading revisionist, was criticized by Gomułka in 1957. He was expelled from the party in 1966 and had to leave Poland in 1968.

Promises Not Kept

Poland welcomed Gomułka's return with relief. He promised to end police terror, allow more freedom of thought and religion, raise wages, and stop collectivization. He kept some of these promises. Production of consumer goods increased a bit. Party leaders and educated people gained more freedom. This was felt as "a certain diversity and revitalization of elite public life." The discussion group Club of the Crooked Circle lasted until 1962. Other forms of community expression and academic freedom lasted until the 1968 Polish political crisis. The allowed academic discussions were very different from how workers were treated. Workers' self-management councils, which formed in 1956, were controlled by the party by 1958. In the communist era, workers had some influence and protection of their economic interests. This was as long as they did not get involved in independent politics or publicly pressure the government.

Economic reform was tried when the Sejm created the Economic Council in 1957. The council included famous economists. They suggested a market reform. It would start by giving businesses more self-rule and independent decision-making. But the suggested economic improvements were not compatible with the strict central economic system. The reform effort failed.

In October 1957, Poland's Foreign Minister Adam Rapacki proposed a European nuclear-free zone. It would include Poland, West Germany, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia. In August 1961, the new Berlin Wall made the division of Europe permanent.

From 1948–71, the Polish government signed agreements with Western European countries, Canada, and the United States. These agreements paid for losses suffered by citizens and companies due to the war and later nationalization. The agreement with the U.S. followed a visit by Vice President Richard Nixon in August 1959. It was signed in 1960. The agreed amount was paid by the Polish government in twenty parts. The U.S. government then took responsibility for claims from U.S. citizens.

After the first reforms, Gomułka's government started to go back on its promises. Control over media and universities was slowly tightened. Many younger, more reform-minded party members were forced out. Over 200,000 were removed in 1958. The Gomułka who promised reforms in 1956 became the strict Gomułka of the 1960s. Poland had a stable period in that decade, but the hopes of "Polish October" faded. Decisions made in 1963 ended the post-October liberalization. Gomułka's allies were replaced by his own people. This was clear when Roman Zambrowski, a leading Jewish politician, was removed from the Politburo.

Poland under Gomułka was seen as one of the more liberal communist states. However, Poles could still go to prison for writing political satire about the party leader, like Janusz Szpotański. Or for publishing a book abroad. In March 1964, a "Letter of the 34" signed by leading intellectuals criticized worsening censorship. It demanded a more open cultural policy, as promised by the constitution. Jacek Kuroń and Karol Modzelewski were expelled from the party and imprisoned in 1965. They wrote a criticism of party rule. They accused the government of betraying the workers' cause. Like many younger Polish reformers, they spoke from leftist positions.

As the government became less liberal, Gomułka's popularity dropped. His initial vision lost its power. Many Poles found Gomułka's self-righteous attitude annoying. He reacted to criticism by refusing to change. He surrounded himself with friends, like Zenon Kliszko. Within the party, Minister of the Interior Mieczysław Moczar and his nationalist-communist group, "the Partisans," looked for a chance to take control.

By the mid-1960s, Poland faced economic problems. Improvements in living standards slowed down. From 1960–70, real wages for workers grew only 1.8% per year. The post-war economic boom was ending. The increasingly global economy was not good for national economies with trade barriers. Like other communist countries, Poland spent too much on heavy industry, weapons, and big projects. It spent too little on consumer goods. The failure of Soviet-style collectivization meant land went back to farmers. But most farms were too small to be successful. Farm productivity remained low. Economic ties with West Germany were frozen. Gomułka blamed economic decline on bad implementation of party plans. He did not understand the role of the market. His government did not create foreign debt.

From 1960, the government used more anti-Catholic policies. This included anti-religious propaganda and making religious practices harder. Gomułka was the last Polish politician who seriously tried to carry out an anti-clerical program. In 1965, Polish bishops sent a Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish Bishops to the German Bishops. In 1966, celebrations of 1,000 years of Christianization of Poland were led by Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. These became huge displays of the Catholic Church in Poland's power. The government held its own national celebrations. But the Church's ability to draw huge crowds impressed Catholic leaders. Talks between the state and church, symbolized by independent Catholic deputies in parliament, quickly worsened.

1968 Events

By the 1960s, rival officials began to plot against Gomułka. Poland's security chief, Mieczysław Moczar, used nationalistic talk and anti-Jewish feelings to gain support. He became the main challenger. The party leader in Upper Silesia, Edward Gierek, also emerged as a possible leader. Gierek was favored by more practical party members. From January 1968, Polish opposition groups were strongly influenced by the Prague Spring movement.

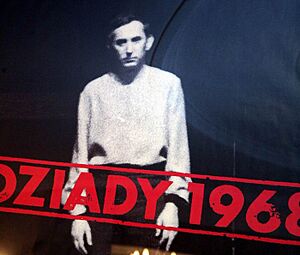

In March 1968, student protests broke out at the University of Warsaw. This happened after the government banned the play Dziady by Adam Mickiewicz at the National Theatre. It was banned for alleged "anti-Soviet references." Later, the ORMO and other security forces attacked protesting students in several cities.

In the March 1968 events, Moczar used the protests to start an anti-intellectual and anti-Semitic campaign. This campaign was officially called "anti-Zionist." Its real goal was to weaken the pro-reform party group. Thousands of Jewish people lost their jobs. About 15,000 Jews left Poland between 1967 and 1971. Only a few thousand remained of what was once Europe's largest Jewish community.

Other victims were college students. Many were expelled and had their careers ruined. Teachers who defended students were also affected. Warsaw University had several departments closed. Liberal educated people, Jewish or not, were removed from government jobs. Leftist thinkers and student leaders lost faith in the socialist government. Finally, the party itself removed thousands of members who did not fit the new environment of intolerance. The 1968 purges also meant a big change in party leadership. Older communist members were removed. People whose careers started in People's Poland took their place. This gave Gomułka's successor, Edward Gierek, one of the youngest power elites in Europe.

The focus on educated dissidents in 1968 overshadowed a similar awakening among Polish workers. Gdańsk, where thousands of students and workers fought the police on March 15, had the highest rate of arrests. Most people arrested in March and April 1968 were classified as "workers."

An internal attempt was made to discredit Gomułka. But he tolerated some parts of the witch hunt. Meanwhile, the Moczar movement caused lasting damage to society. Gomułka's government regained control. It was saved by international and domestic factors. The Moczar group could not take over the party. The Soviet Union, led by Leonid Brezhnev, was busy with the crisis in Czechoslovakia. It did not want to change Polish leadership.

In August 1968, the Polish People's Army took part in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Some Polish intellectuals protested. Ryszard Siwiec burned himself alive during an official holiday. Poland's role in crushing the Czech liberalization movement further separated Gomułka from his former liberal supporters. But within the party, opposition to Gomułka faded. The 5th Congress of the PZPR confirmed his rule in November. Brezhnev, who attended, used the chance to explain his Brezhnev Doctrine. This doctrine said the Soviet Union had the right to use force if an allied state moved too far from the "fraternal course."

Treaty with West Germany, Food Riots, and Gomułka's Fall

In December 1970, Gomułka's government had a big political success. West Germany recognized Poland's post-World War II borders. In talks for the Treaty of Warsaw, Germany secured the right for Germans in Poland to move to West Germany. They could also help financially those who stayed. Hundreds of thousands were affected. German Chancellor Willy Brandt signed the agreement. He knelt and asked for forgiveness for Nazi crimes. This gesture was understood in Poland as being for all Poles. The reconciliation process between Poland and Germany had started five years earlier. Polish Church leaders had sent a letter of reconciliation to German bishops. The Polish government had criticized it then.

Gomułka felt proud and secure after the treaty. It was his big political achievement. It showed a lasting trend in Poland's foreign policy: reducing dependence on Russia and building good relations with Germany for security.

But this event could not hide Poland's growing economic crisis. Fixed, artificially low food prices kept city people calm. But it caused economic strain. The situation could not last. On 12 December 1970, the government suddenly announced big increases in basic food prices. The new prices were hard for many workers to understand. The timing was bad (before Christmas). This led to strong public reaction and Gomułka's fall.

From 14–19 December 1970, mass protests against price rises broke out in northern cities like Gdańsk, Gdynia, Elbląg, and Szczecin. In violent clashes, 19 public buildings were destroyed or damaged. This included party headquarters in Gdańsk and Szczecin. The PZPR Central Committee was meeting in Warsaw. But a smaller group, led by Gomułka, allowed limited use of deadly force. Gomułka wanted to end the conflict forcefully. Party leaders like Zenon Kliszko and Stanisław Kociołek directed local actions. In Gdynia, soldiers were told to stop protesters from returning to factories. They fired into a crowd of workers leaving trains. Deadly clashes also happened in Szczecin. About fifty people were killed in the coastal region in December.

The protests spread to other cities. More strikes happened. Angry workers took over many factories. A general strike across Poland was planned for 21 December 1970.

The party leaders met in Warsaw on 20 December. They saw the danger the worker revolt posed to their system. After talking with worried Soviet leaders, they arranged for Gomułka to resign. He was stressed and ill. Several of his helpers were also removed. Edward Gierek became the new first secretary. Mieczysław Moczar, another strong candidate, was not trusted by the Soviets.

Another strike in Szczecin broke out on 22 January 1971. Gierek gambled that his personal visits would solve the crisis. He went to Szczecin on 24 January and to Gdańsk the next day. He met the workers, apologized for past mistakes, and said he understood their problems as a former worker. He promised to govern for the people. Szczecin strikers demanded freely elected worker councils and union representatives. Gierek agreed. But in reality, officials soon pushed worker leaders out of legal labor groups and their jobs. The February 1971 Łódź strikes followed, focusing on economic demands. Afterward, prices were lowered, wage increases announced, and big economic and political changes were promised.

The Polish opposition, usually led by educated people, was in disarray after the blows of 1968 and 1970. Their weak connection with the communist party was broken. But a new plan had not yet appeared. However, in 1971, Leszek Kołakowski published an important article. It suggested a civil resistance movement that would work even in a repressed socialist society.

Gierek's Decade (1970–1980)

Catching Up with the West

Gierek, like Gomułka in 1956, came to power with many promises. He said everything would be different: wages would rise, prices would stay stable, there would be free speech, and those responsible for the violence would be punished. People believed Gierek was honest. His promises bought him some time. He started a new economic plan. It was based on borrowing large amounts of money from Western banks. This money was to buy technology to improve Poland's exports. This huge borrowing, over 24 billion US dollars during Gierek's years, was for equipment and modernizing Polish industry. It was also for importing consumer goods to motivate workers.

For the next few years, the government tried reforms. For the first time, many Poles could buy cars, televisions, and other luxury items. Attention was paid to workers' wages. Farmers no longer had to deliver goods to the state. They were paid higher prices for their products. Free health service was finally given to rural, self-employed Poles. Censorship was eased. Poles could travel to the West and keep foreign contacts easily. Relations with Polish people living abroad improved. This cultural and political relaxation led to more freedom of speech. Big investments and Western technology purchases were expected to improve living standards. They were also meant to create competitive Polish industry and agriculture. Modernized factories would lead to more Polish exports to the West. This would bring in foreign money to pay off debts.

This "New Development Strategy" relied on global economic conditions. The plan failed suddenly due to a worldwide recession and higher oil prices. The 1973–74 oil crisis caused inflation and a recession in the West. This led to a sharp rise in prices of imported goods in Poland. Demand for Polish exports, especially coal, also fell. Poland's foreign debt, which was zero when Gomułka left, grew quickly under Gierek. It reached billions of dollars. Continuing to borrow from the West became harder. Consumer goods started to disappear from Polish shops. The new factories built by Gierek's government were often ineffective. They were badly managed. The basics of market demand and cost effectiveness were often ignored. The big internal economic reform promised by Gierek's team did not happen.

Western loans helped industry grow and supported Gierek's policy of consumerism. But only for a few years. Industrial production grew by 10% per year from 1971 to 1975. These years are remembered by many older Poles as the most prosperous. But growth dropped to less than 2% in 1979. Debt servicing took 12% of export earnings in 1971. It rose to 75% in 1979.

In 1975, Poland signed the Helsinki Accords. This was possible because of "détente" between the Soviet Union and the United States. Despite promises, there was little change in freedoms in Poland. However, Poles became more aware of their rights. They were encouraged by their government's treaty promises.

Gierek's government faced growing problems. This led to more dependence on the Soviet Union. The constitution, changed in February 1976, made the alliance with the Soviet Union official. It also confirmed the communist party's leading role. The wording of the changes was softened after protests by intellectuals and the Church. But the government felt it needed more authority due to debt and economic crisis. The issues raised helped unite the growing political opposition.

Gierek's government focused less on Marxist ideas. From his time, Poland's "communist" governments focused on practical issues. New trends started in Polish economic policy. These included focusing on individual effort and competition. Some saw this as an attack on egalitarianism (social equality). Social inequalities did increase. Parts of the educated class, party officials, and small businesses formed a new middle class. The new "socialist" ways were less strict. They stressed innovation and modern management. They also involved workers. All this was seen as needed to move the economy past constant crises. Poland in the 1970s became more open to the world. It joined the global economy. This changed society forever. It also created new economic problems. Opposition ideas, promoting active individuals, grew alongside these changes.

New Social Unrest and Organized Opposition

Because of the 1970 worker protests, food prices stayed frozen and artificially low. Demand for food was higher than supply. This was also because real wages increased. In the first two years of Gierek's rule, wages rose more than in the entire 1960s. In June 1976, the government tried to raise prices. Basic food prices went up by 60% on average. This was three times the rate of Gomułka's increases six years before. Wage increases were skewed towards richer people. This led to an immediate nationwide wave of strikes. There were violent protests at the Ursus Factory near Warsaw, in Radom, Płock, and other places. The government quickly backed down and canceled the price rises. But strike leaders were arrested. The party leaders staged "spontaneous" public gatherings. They wanted to show "anger of the people" at the "trouble-makers." But Soviet pressure stopped further price increases. Gierek's good relations with Leonid Brezhnev were now damaged. Food ration cards, introduced in August 1976, remained a part of life in Poland. The government's retreat, for the second time, was a big defeat. The government could not reform or meet people's basic needs. It had to sell everything abroad to pay foreign debts. The government was in a difficult spot. People suffered from lack of necessities. Organized opposition found room to grow.

Because of the 1976 protests and arrests, a group of intellectuals formed the Workers' Defence Committee (KOR). Its goal was to help workers who were victims of the 1976 repression. The KOR supported workers' movements. The dissidents saw that the working class was key to resisting the government's abuses. The new opposition was increasingly an alliance of educated people and workers. The KOR was the core of organized opposition. It helped other opposition groups form. More groups soon followed. These included the Movement for Defense of Human and Civic Rights (ROPCiO), Free Trade Unions of the Coast (WZZW), and the Confederation of Independent Poland (KPN). The newspaper Robotnik ('The Worker') was given out in factories from September 1977. The idea of independent trade unions was first raised by Gdańsk and Szczecin workers in 1970–71. Now it was developed by the KOR. This led to the Free Trade Unions in 1978, which was the start of Solidarity. The KPN was the smaller right-wing part of the Polish opposition. Opposition members tried to resist the government by saying it broke the Constitution of the Polish People's Republic, Polish laws, and international agreements.

For the rest of the 1970s, resistance grew. It took forms like student groups, secret newspapers and publishers, importing books, and a "Flying University." The government used various ways to stop these movements.

Polish Pope John Paul II

On 16 October 1978, Poland experienced what many Poles believed was a miracle. Cardinal Karol Wojtyła, the archbishop of Kraków, was elected pope at the Vatican. He took the name John Paul II. The election of a Polish pope had a huge effect on Poland. When John Paul visited Poland in June 1979, half a million people welcomed him in Warsaw. In the next eight days, about ten million Poles attended his outdoor masses. John Paul clearly became the most important person in Poland. He was not so much opposed as ignored by the government. Instead of calling for rebellion, John Paul encouraged an "alternative Poland." This meant social groups independent of the government. So, when the next crisis came, the nation would be united.

Polish People Abroad

The Polish government-in-exile in London was not recognized after World War II. It was made fun of by the communists. But for many Poles, it was very important. Under President Edward Bernard Raczyński, it overcame internal fights. After the Polish pope was elected and Polish opposition grew, its image improved.

Large Polish communities in North America, Western Europe, and elsewhere were politically active. They strongly supported those struggling in Poland. The anti-communist American Polonia and other Poles were grateful for President Ronald Reagan's leadership. Important Polish groups in the West included Radio Free Europe, run by Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, and the monthly literary Kultura magazine in Paris, led by Jerzy Giedroyc.

Last Years of the Polish People's Republic (1980–1989)

Failing Economy and Worker Unrest

By 1980, the government had to try again to raise consumer prices to a real level. But they knew this would likely cause another worker rebellion. Western financial companies told the government in April 1980 that it could no longer pay for artificially low prices of consumer goods. The government gave in after two months. On 1 July, it announced gradual price rises, especially for meat. A wave of strikes and factory occupations began at once. The biggest ones happened in Lublin in July.

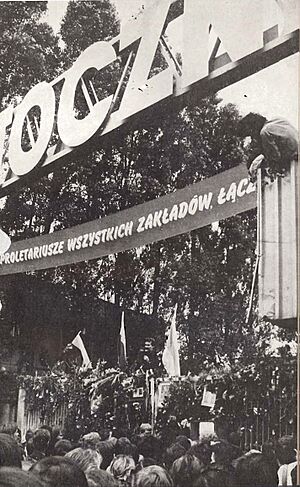

The strikes reached the politically important Baltic Sea coast. A sit-down strike began at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk on 14 August. Among the strike leaders were Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa. Wałęsa was a shipyard electrician who had been fired. He led the strike committee. The Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee made a list of 21 demands on 17 August. The strikes spread along the coast, closing ports and stopping the economy. With help from activists from the KOR and other intellectuals, workers organized as a united front. They were not just asking for better pay. They made a key demand: to create trade unions independent of government control. Other issues included rights for the Church, freeing political prisoners, and better health services.

The party leaders had a choice. They could use massive force or make a friendly agreement. They chose the latter. On 31 August, Wałęsa signed the Gdańsk Agreement with Mieczysław Jagielski, a party leader. The agreement recognized workers' right to form free trade unions. It also made the government promise to end censorship, stop weekend work, raise the minimum wage, improve welfare and pensions, and give more freedom to factories. The party's power was weakened but still recognized. Poland's international alliances were also recognized. More moderate groups saw this as necessary to prevent Soviet intervention. The opposition negotiators did not worry about the cost of the economic promises. A wave of national excitement swept the country. Similar agreements were signed in other strike centers: in Szczecin (the Szczecin Agreement), Jastrzębie-Zdrój, and at Katowice Steelworks.

Solidarity

The Gdańsk Agreement was a big step. It led to a meeting of independent union representatives on 17 September in Gdańsk. This meeting formed the trade union "Solidarity" (Polish Solidarność). It was led by Lech Wałęsa. The idea of independent unions spread quickly across Poland. Solidarity groups formed in most workplaces and regions. After overcoming government efforts to stop it, Solidarity was finally registered in court as a national labor union in November. In early 1981, a network of union groups was set up in major factories.

At first, Solidarity was a non-political movement. It aimed to rebuild civil society. But in 1980, Solidarity became legal and important. It and the Polish opposition did not have a clear plan for the future. In 1981, Solidarity took on a political role. It helped form a broad social movement against the ruling system. This movement was led by workers. It included members from the Catholic Church to non-communist leftists. The union was supported by intellectual dissidents. It followed a policy of nonviolent resistance. According to Karol Modzelewski, Solidarity in 1980–81 was based on the idea of friendship between educated people and workers. In ideas and politics, Solidarity followed its allied intellectuals.

Solidarity's actions, though about union matters, were seen as the first step to ending the government's control over social groups. Because of conditions in socialist society, Solidarity soon lost its focus on labor. It became a movement for civic rights and an open society. Removing the ruling party or breaking free from the Soviet Union was not on the agenda. The union used strikes to block government policies. The goals of the first Solidarity (1980–81) were to reform socialism. It did not want to bring back private ownership or capitalism. Solidarity was an egalitarian movement. It did not ask for property taken by the state after World War II to be returned. Solidarity was socialist, and social justice was its goal. The first Solidarity uprising can also be seen as workers rebelling against new capitalist features. These features reduced their role in Gierek's society. It also had an "anti-politics" approach, building civil society without the state or market. People strongly against communism were a small minority in the first Solidarity. It included one million communist party members. Besides workers, farmers and students also created their own groups: Rural Solidarity and Independent Students' Union. They were recognized by the government after strikes in January 1981.

In September 1980, after the labor agreements, First Secretary Gierek was removed. Stanisław Kania replaced him as party leader. Like his predecessors, Kania made promises the government could not keep. This was because officials were stuck. If they followed economic needs, they would cause political instability. The gross national income fell by 2% in 1979, 8% in 1980, and 15–20% in 1981.

At a communist meeting in December 1980 in Moscow, Kania argued with Leonid Brezhnev and other Warsaw Pact leaders. They pushed for military intervention in Poland. Kania and Defense Minister Wojciech Jaruzelski said they would fight the "counterrevolution" in Poland themselves. They believed there was still a chance for Solidarity's working-class side to win, not the anti-socialist elements. President Jimmy Carter and President-elect Ronald Reagan called Brezhnev. The intervention was postponed. Meanwhile, Solidarity, not fully aware of the danger, did its work. It practiced democracy in the union and pushed for a sovereign society. The independent unions tried to "recapture public life from the monopoly control of the party." On 16 December 1980, the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970 was unveiled in Gdańsk. This marked a high point for Solidarity.

Mass protests happened at that time. These included a general strike in Bielsko-Biała in winter 1981. There was also a nationwide warning strike in spring. And hunger protests in summer. The warning strike followed the Bydgoszcz events (March 1981). During these events, officials used violence against Solidarity activists. The planned general strike was called off after Solidarity made a deal with the government. But negotiators worked under threat of Soviet intervention. Wałęsa's compromise prevented a fight with the government. But the protest movement lost some of its energy. In the following months, Solidarity grew weaker. Its popular support was no longer able to lead mass actions.

Minister Jaruzelski also became prime minister in February 1981. In June, the Soviet Central Committee pressured the Polish party for a leadership change. But Jaruzelski received strong support from military members of the Polish Central Committee. The IX Congress of the PZPR took place in July. Kania was reelected first secretary. The party's internal reformers lost.

As the economy worsened and the government avoided reforms, government and Solidarity representatives met in early August. The talks ended in disagreement. During a Solidarity meeting, Modzelewski and Kuroń suggested a democratic change. They proposed that the Union take a major political role. It would help govern the country, take responsibility, and keep social peace. This would ease the ruling party's burdens. Such a deal was seen as the only way forward. But it needed government partners interested in a negotiated solution.

Solidarity's existence and the political freedoms it brought paralyzed the authoritarian state. Daily life became harder. People showed extreme anger. Party officials' hostility towards Solidarity grew quickly.

At a State Defense Committee meeting on 13 September, Kania was warned that the "counterrevolution" must be stopped by martial law. PZPR regional secretaries soon made the same demands. In October, First Secretary Kania stepped down. Prime Minister Jaruzelski became the party chief.

In September and October, the First Congress of Solidarity met in Gdańsk. Wałęsa faced opposition and was barely elected chairman. The delegates passed a radical reform program. It used the word "social" or "socialized" 150 times. The congress called on workers in other East European countries to follow Solidarity. Local, increasingly "political" strikes continued. Wałęsa called them "wildcats." He tried to control them from the center. He tried to reach an agreement with the state. He met General Jaruzelski and Catholic Primate Józef Glemp on 4 November. At that time, the government tried to reduce Solidarity's role. The union had nearly ten million members, almost four times as many as the ruling party. A militant mood and unrealistic demands were shown at a meeting on 3 December. But the authorities recorded the talks. They then broadcast the recordings, which they had manipulated.

The government, without talking to Solidarity, adopted an economic plan. It could only be carried out by force. It asked parliament for special powers. In early December, Jaruzelski was pressured by his generals for immediate forceful action. Their demands were repeated at a Politburo meeting on 10 December. On 11 and 12 December, Solidarity's National Commission declared 17 December a day of countrywide protest. Neither Solidarity nor the government was willing to back down. In Brezhnev's time, there could be no peaceful solution. The Soviets now preferred the conflict to be solved by Polish authorities.

Martial Law Imposed

On 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski cracked down on Solidarity. He claimed the country was about to collapse and that there was a danger of Soviet intervention. Martial law was declared. The free labor union was suspended, and most of its leaders were arrested. Several thousand citizens were held or imprisoned. Polish police (Milicja Obywatelska) and riot police ZOMO stopped strikes and protests. Military forces entered factories to crush the independent union movement. There were violent attacks, including the pacification of Wujek Coal Mine, where 9 people were killed. The martial law actions were mainly against workers and their union. Workers, more than educated activists, were treated most harshly. The authorities succeeded in causing trauma to Solidarity members. The mass movement could not recover. The Catholic Church tried to calm Solidarity before and after martial law.

At first, the government wanted to change Solidarity into a compliant union. It would be stripped of its educated advisers. But most Solidarity leaders refused to cooperate, especially Wałęsa. So the government decided to completely destroy the union movement.

Strikes and protests followed, but they were not as widespread as in August 1980. The last mass street protests by Solidarity happened on 31 August 1982. This was the second anniversary of the Gdańsk agreements. The "Military Council of National Salvation" officially banned Solidarity on 8 October. Martial law was formally lifted in July 1983. But many controls on freedoms and political life, as well as food rationing, stayed in place through the mid-to-late 1980s. Despite restrictions, "the official cultural realm remained far more open than it was prior to 1980." Among the concessions by the troubled government were the Constitutional Tribunal in 1982 and the Polish Ombudsman office in 1987.

In the mid-1980s, many, including most activists, thought Solidarity was a thing of the past. It continued as a small underground group. It was supported by various international groups, from the Catholic Church to the Central Intelligence Agency. When most senior Solidarity figures were arrested, Zbigniew Bujak, head of the Warsaw branch, stayed hidden. He led the secret group until his arrest in 1986. But after martial law, the public showed signs of tiredness and disappointment. It became clear that Solidarity was not a united front.

"Market Socialism" and System Collapse

During the chaotic years of Solidarity and martial law, Poland entered a decade of economic crisis. It was worse than in Gierek's time. Work on big unfinished projects from the 1970s used up available money. Little was left to replace old factory equipment. Manufactured goods were not competitive on the world market. Bad management, poor production organization, and shortages of materials made workers' morale worse. 640,000 working-age people left the country between 1981 and 1988.

Governments under General Jaruzelski (1981–1989) tried market economy reforms. They aimed to improve the economy by ending central planning. They reduced central control. They introduced self-management and self-financing for state businesses. They also allowed self-government by employee councils. The reforms had positive but limited effects. They greatly increased economic knowledge. Some of their achievements were later claimed by Solidarity governments. But businesses' self-rule had to compete with party interference. Officials avoided making life harder for people. Western governments did not want to support what they saw as a communist regime reform. The government allowed more small private businesses. This moved further from the 'socialist' economy model. Old ideas were dropped. Priority was given to practical issues. To improve the economy, the government turned to free market reforms. This included a growing liberal part from the mid-1980s. Marketization, made official by a 1988 law, continued past the mid-1990s. "Market socialism" was introduced as leaders lost faith in the socialist system. Even party managers were threatened by the declining economy. Businesses were supposed to become independent and self-financing. This included workers' councils that resisted changes. Owners of private businesses did well in the final years of the People's Republic. The number of such businesses increased. Foreign investment was also encouraged. But limited marketization did not turn the economy around. Centralized economic decision-making continued. Newly independent businesses moved towards a chaotic partial privatization. This included some corruption. On a more basic level, many ordinary Poles took advantage of the changes. They got involved in many ways to earn money.

The worsening economic crisis made life much harder for ordinary citizens. It led to more political instability. Rationing and queuing became normal. Ration cards were needed to buy basic goods. The government used ration cards to avoid market control of income and prices. This was to prevent social unrest. Western banks no longer wanted to lend money to the bankrupt Polish government. Access to goods Poles needed became even more limited. Most scarce foreign money had to be used to pay Poland's huge foreign debt. It reached US$27 billion by 1980 and US$45 billion in 1989. The government controlled all official foreign trade. It kept a very artificial exchange rate with Western currencies. This exchange rate made economic problems worse. It led to a growing black market and a shortage economy. The widespread underground economy involved bribery, waiting lists, speculation, and direct exchanges between businesses. A large part of personal incomes came from side activities. Society declined. The environment, physical, and mental health also worsened. Death rates kept increasing. In the late 1980s, the PZPR feared another social explosion. This was due to high inflation, low living standards, and growing public anger. The authorities themselves felt confused and powerless.

Last Years and Transition (1980–1989)

Towards Round Table Talks and Elections

In September 1986, the government announced a general amnesty. It began working on several important reforms. With a more open political environment, Wałęsa was asked to restart the National Commission from the first Solidarity. But he refused. He preferred to work with Solidarity's Expert Commission advisers. A National Executive Commission, led by Wałęsa, was openly formed in October 1987. Other opposition groups started street protests. These included the Fighting Solidarity, the Federation of Fighting Youth, and the Freedom and Peace Movement. The Orange Alternative "dwarf" movement organized colorful events. The liberal magazine Res Publica was allowed to be officially published.

In the 1987 Polish political and economic reforms referendum, 67% of voters participated. Most approved the government's reforms. But a formal public approval was missed. This was because the government set very strict rules for passing the referendum. This failure hurt the market-oriented economic reforms.

The ruling communist leaders slowly realized they would need a deal with the opposition. This deal would have to include leading Solidarity figures. Solidarity as a labor union could not regain its strength after martial law. It was almost destroyed later in the 1980s. But it remained a symbol that helped people accept big changes. The Solidarity organization as a mass movement, and its main social democratic part, had been defeated. Solidarity's name was still used. But the opposition movement split into different political groups. A new idea among intellectuals was that "democracy was based on private property and a free market." This view no longer meant wide political participation. It focused instead on elite leadership and a capitalist economy. Solidarity became a symbol. Its activists openly took "anti-communist" positions. Its leadership moved to the right. The historic mass movement was now represented by a few people. Lech Wałęsa, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, and Leszek Balcerowicz were about to play key roles. They supported a free market. They were strongly influenced by American and West European financial interests.

Jaruzelski's Poland depended on cheap goods from the Soviet Union. Big Polish reforms were not possible under the last three conservative Soviet leaders. The perestroika and glasnost policies of the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, were key to reforms in Poland. Gorbachev basically rejected the Brezhnev Doctrine. This doctrine said the Soviet Union would use force if its Eastern European countries tried to leave the communist bloc. Changes in the Soviet Union changed the international situation. They gave Poland a historic chance for independent reforms. US President Ronald Reagan's strong stance also helped. David Ost stressed Gorbachev's positive influence. With his support for Poland and Hungary joining the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Gorbachev pushed the region towards the West.

Nationwide strikes broke out in spring and summer 1988. They were weaker than the 1980 strikes. They stopped after Wałęsa stepped in. He got the government to promise to start talks with the opposition. The strikes were the last active political involvement of the working class in People's Poland. They were led by young workers. These workers were not connected to old Solidarity members. They opposed the harmful effects of the economic changes happening. According to researcher Maciej Gdula, the political activity that followed was only by elites. It was not inspired by or discussed with any mass social group. The opposition leaders no longer felt strongly committed to workers' welfare. Polish dissidents were no longer secure as leaders. They were eager to bargain with the weakened government. They now shared the government's economic goals.

Both sides were pushed by the new international situation and the recent strikes. In September 1988, preliminary talks began between government and Solidarity leaders in Magdalenka. Many meetings happened. Wałęsa and Minister of Internal Affairs, General Czesław Kiszczak, were involved. In November, Wałęsa debated Alfred Miodowicz, head of the official trade unions, on national TV. This improved Wałęsa's image.

At a PZPR meeting from 16–18 January 1989, General Jaruzelski and his group overcame resistance. They threatened to resign. The party decided to allow Solidarity to be legal again. They would talk formally with its leaders. From 6 February to 4 April, 94 negotiation sessions took place. These were called the "Round Table Talks." They led to political and economic compromises. Jaruzelski, Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski, and Wałęsa did not directly take part. The government side included Czesław Kiszczak and others. The Solidarity opposition included Adam Michnik, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Bronisław Geremek, and Jacek Kuroń. The talks resulted in the Round Table Agreement. Political power would go to a new two-chamber parliament and a president.

By 4 April 1989, many reforms and freedoms for the opposition were agreed. Solidarity, now the Solidarity Citizens' Committee, would be legal again as a trade union. It could take part in semi-free elections. These elections had limits to keep the PZPR in power. Only 35% of seats in the Sejm, the main lower parliament chamber, would be open to Solidarity candidates. The other 65% were for the PZPR and its allies. The Round Table Agreement only called for reform, not replacement, of "real socialism." The party thought the election would neutralize conflict and keep them in power. But the agreed social policies were quickly dropped by both the party and the opposition.