Oder–Neisse line facts for kids

The Oder–Neisse line is the modern border between Germany and Poland. It mostly follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers. These rivers flow into the Baltic Sea in the north. A small part of Poland, including the cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście, is actually west of this line.

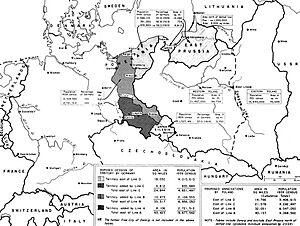

After World War II, all German lands east of this line became part of Poland. This was decided at the Potsdam Conference. This area was about a quarter of Germany's size before the war. The northern part of East Prussia, including the city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), went to the Soviet Union. Many German people, around 12 million, had already left these areas as the Soviet army advanced.

The Oder–Neisse line was the border between East Germany and Poland from 1950 to 1990. Both governments agreed to it in 1950. West Germany accepted the border later, in 1972. After Germany became one country again in 1990, the new German–Polish Border Treaty confirmed this line as the official border.

Contents

Understanding the Oder–Neisse Border

How the Border Changed Over Time

The lower part of the Oder River in Silesia was Poland's western border a long time ago, from the 900s to the 1200s. After World War I, some people thought this old border should be brought back. They believed it would help protect Poland from Germany.

Later, when the Nazis came to power in Germany, they made the German land east of this line ready for war. Polish people living there faced pressure to become more German. The Nazis also encouraged German people living in Poland to be very nationalistic.

Many areas between the Oder–Neisse line and Poland's old border were still Slavic-speaking even in the 1800s. For example, on Rügen Island, the local Slavic culture lasted until the 1800s. This was also true for parts of Farther Pomerania and Lower Silesia.

Poland's Border Before World War II

Before World War II, Poland's western border with Germany was set by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. This border partly followed an old line between the Holy Roman Empire and Greater Poland. But it was changed a bit to reflect where different ethnic groups lived.

For example, the people of Upper Silesia voted in 1921 on whether to join Germany or Poland. About 60% voted for Germany. This vote caused a lot of tension and even some fighting. In the end, the region was divided.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Poland wanted the city of Danzig to be part of Poland. They said it was historically Polish. However, by 1919, most people in Danzig were German. So, the Free City of Danzig was created. It was a city-state where Poland had some special rights.

Ideas for a New Polish Border

The idea of the Oder–Neisse line as a future Polish border started to appear in the late 1800s. Some Polish thinkers believed that lands like Upper Silesia and parts of East Prussia should return to Poland. They saw it as correcting historical wrongs.

At the Paris Peace Conference, Polish leaders suggested a border that would include all of Upper Silesia and most of Opolian Silesia. They also wanted all of Greater Poland, Danzig, Warmia, and Masuria. While some leaders at the conference agreed, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, strongly disagreed. This led to fewer changes in Poland's favor at that time.

Decisions During World War II

Why the Border Idea Grew

Between the two World Wars, some Polish nationalists believed in "Western thought." This idea said that Poland's "motherland territories" included areas that were part of Piast Poland in the 900s. Some even wanted Poland's border to reach the Elbe River.

After Nazi Germany attacked and took over Poland, many Polish politicians felt the border with Germany had to change. A safe border was seen as very important, especially after the terrible things the Nazis did. Changing the border was seen as a punishment for Germany and a way to make up for Poland's losses.

At first, the Polish government that was in exile (living outside Poland) wanted to add East Prussia, Danzig, and the Oppeln region of Silesia to Poland. They also wanted to make the border straighter in Pomerania. They believed these changes would give Poland a safer border.

As the war went on, these ideas changed. In 1941, the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin said that East Prussia should "return to Slavdom." He also suggested that Poland should get all German land up to the Oder River.

Tehran and Yalta Conferences

At the Tehran Conference in 1943, Stalin brought up the idea of Poland's western border moving to the Oder River. The American President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, agreed that Poland's border should move west to the Oder. He also agreed that Poland's eastern borders should shift west.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, American and British leaders met. They agreed on the basic ideas for Poland's future borders. In the east, Poland would give up land to the Soviet Union. In the west, Poland would get parts of East Prussia, Danzig, eastern Pomerania, and Upper Silesia.

Stalin then said that the Polish Prime Minister in exile was happy that Poland would get Szczecin and German lands east of the Western Neisse River. This was the first time the Soviets openly supported the Western Neisse as the border. The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, worried that giving Poland so much German land would cause problems. He said it would be "a pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food that it got indigestion." Stalin replied that many Germans had already fled from the Red Army. The final decision on Poland's western border was left for the Potsdam Conference.

Polish and Soviet Requests

Originally, Germany was supposed to keep Szczecin, and Poland would get East Prussia with Königsberg. But Stalin wanted Königsberg for the Soviet Navy as a port that wouldn't freeze in winter. So, he said Poland should get Szczecin instead.

The Polish government in exile had little say in these choices. But they wanted to keep the city of Lwów (now L'viv) in eastern Poland. Stalin refused. Instead, he suggested that all of Lower Silesia, including Breslau (now Wrocław), be given to Poland. Many Poles from Lwów later moved to Wrocław.

The final border was not the biggest change suggested. Some people wanted to include areas even further west, like where the Slavic Sorbs lived near Cottbus.

The exact spot of the western border was still unclear. The Western Allies generally agreed the Oder would be the border. But they weren't sure if it should follow the eastern or western Neisse River. They also debated if Szczecin, which is west of the Oder, should stay German or go to Poland. Szczecin was an important port for Berlin. The Western Allies wanted the border on the eastern Neisse. But Stalin refused.

The Potsdam Conference Decisions

At the Potsdam Conference in 1945, Stalin argued for the Oder–Neisse line. He said the Polish government wanted this border and that no Germans were left east of it. Later, the Russians admitted that at least a million Germans were still there. Polish Communist leaders came to the conference to argue for the Oder–Western Neisse border. They said the port of Szczecin was needed for exports from Eastern Europe.

Agreements and Concessions

The US Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes, said the US would let Poland manage the area east of the Oder and Eastern Neisse. This was in exchange for the Soviets reducing their demands for war payments from the Western zones. An Eastern Neisse border would have left Germany with about half of Silesia, including most of Wrocław. But the Soviets insisted that the Poles would not accept this.

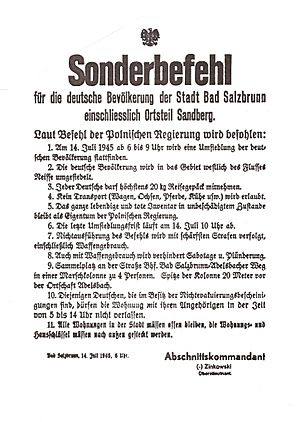

On August 2, 1945, the Potsdam Agreement was signed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. This agreement placed the German lands east of the Oder–Neisse line under Polish control. It was also decided that all Germans remaining in these new Polish territories should be moved out.

The "Recovered Territories"

These new lands were called the "Recovered Territories" in Poland. This name came from the idea that they were historically part of Poland. The term was used by the Communist government to make Polish settlers feel loyal to the new system. Poland gained about 112,000 square kilometers of former German land. In return, Poland gave up about 187,000 square kilometers of land east of the Curzon Line to the Soviet Union.

One reason for this new border was that it was the shortest possible border between Poland and Germany. It is only 472 kilometers long.

After World War II

The new border moved deep into what was Germany in 1937. This area had mostly German people. Almost all of Silesia, more than half of Pomerania, eastern Brandenburg, and parts of East Prussia became part of Poland. The northeastern part of East Prussia went to the Soviet Union.

These border changes led to large movements of people. Nearly all Germans remaining in the areas taken by Poland were moved out. At the same time, Polish people who had been forced to work in Germany during the war returned. Also, many Poles from the eastern parts of Poland, which were now part of the Soviet Union, were moved to these new territories.

Most Poles supported the new border. They feared Germany attacking again. The border was also seen as a fair result for Germany starting World War II and the terrible things they did. It also made up for Poland losing land to the Soviet Union in the east.

The United States did not formally recognize the Oder–Neisse line until 1989-1990. However, by the mid-1960s, the US government had largely accepted it as the final border.

Germany Accepts the Border

East Germany's View

East Germany's ruling party at first did not accept the Oder–Neisse line. But under pressure from the Soviet Union, they started calling it the "border of peace." In 1950, East Germany and Poland signed the Treaty of Zgorzelec. This treaty officially recognized the Oder–Neisse line as the "Border of Peace and Friendship."

In 1952, Stalin said that if the Soviet Union agreed to Germany becoming one country again, Germany had to accept the Oder–Neisse line as a permanent border. West Germany's leader, Konrad Adenauer, rejected this offer.

West Germany's View

West Germany believed that Germany's official borders were those from 1937. They said that the Potsdam Agreement only put the lands east of the Oder–Neisse line under Polish control temporarily. They felt the final border should be decided in a peace treaty.

Many Germans who had been moved from these eastern lands lived in West Germany. They formed a strong political group. Because of this, West German leaders, including Adenauer, often said they would not accept the Oder–Neisse line as permanent. They wanted to win the votes of these people.

However, this stance caused problems for West Germany with its Western allies. Many countries thought West Germany's view on the border was not good.

In 1970, West Germany's leader, Willy Brandt, changed the country's policy with his Ostpolitik. West Germany signed treaties with the Soviet Union and Poland. These treaties recognized Poland's western border at the Oder–Neisse line as the current reality. They also agreed that the border would not be changed by force. This made it easier for Germans who had been moved to visit their old homes.

In 1989, another treaty was signed between Poland and East Germany. This treaty defined the sea border and settled an old dispute.

In March 1990, the West German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, at first suggested that a reunified Germany might not accept the Oder–Neisse line. He later changed his mind after a big international reaction. In November 1990, after German reunification, Germany and Poland signed a treaty confirming the Oder–Neisse line as their border. Germany also changed its constitution to remove any way to claim the former German eastern territories.

The German-Polish Border Treaty became official in 1992. Another treaty, the Treaty of Good Neighbourship, was signed in 1991. It recognized the rights of German and Polish minorities living on both sides of the border. After 1990, about 150,000 Germans still lived in the areas transferred to Poland.

Other Important Points

Cities Divided by the Border

The border divided several cities into two parts. Examples include Görlitz (Germany) and Zgorzelec (Poland), Guben (Germany) and Gubin (Poland), and Frankfurt (Germany) and Słubice (Poland).

Open Border (1971–1980)

Between 1971 and 1980, the border was partially open. Millions of people visited the neighboring country. Polish tourists often went to East Germany to buy cheaper products.

See also

In Spanish: Línea Óder-Neisse para niños

In Spanish: Línea Óder-Neisse para niños

- Curzon Line

- Federation of Expellees

- Allied Occupation Zones in Germany

- Vistula-Oder Offensive, a military operation in 1945

- Malta Conference, a meeting in 1945

- Yalta Conference, a major meeting of Allied leaders in 1945

- Battle of Königsberg, a battle in 1945

- Battle of the Oder-Neisse, a battle in 1945

- Potsdam Conference, a meeting of Allied leaders in 1945

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |