Helmut Kohl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Helmut Kohl

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

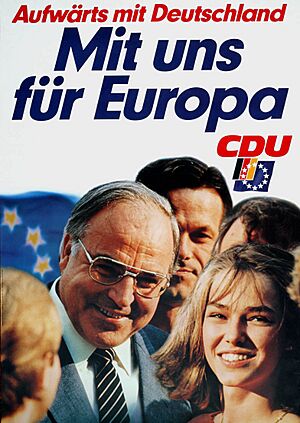

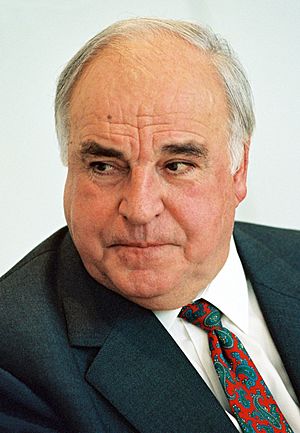

Kohl in 1996

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of Germany | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 October 1982 – 27 October 1998 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice-Chancellor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Helmut Schmidt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Gerhard Schröder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Christian Democratic Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 June 1973 – 7 November 1998 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Rainer Barzel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Wolfgang Schäuble | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 13 December 1976 – 1 October 1982 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Helmut Schmidt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Karl Carstens | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Herbert Wehner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the CDU/CSU group in the Bundestag | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 13 December 1976 – 4 October 1982 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief Whip | Philipp Jenninger | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy | Friedrich Zimmermann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Karl Carstens | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Alfred Dregger | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 May 1969 – 2 December 1976 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Otto Meyer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Peter Altmeier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Bernhard Vogel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl

3 April 1930 Ludwigshafen, Bavaria, German Reich |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 June 2017 (aged 87) Ludwigshafen, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Cathedral Chapter Cemetery, Speyer, Rhineland-Palatinate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | CDU (from 1946) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

Hannelore Renner

(m. 1960; died 2001)Maike Richter

(m. 2008) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Heidelberg University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

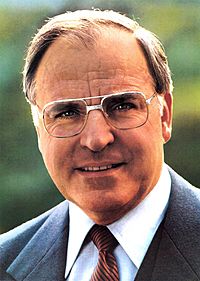

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (born April 3, 1930 – died June 16, 2017) was a German politician. He served as the Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998. He was also the leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party from 1973 to 1998.

Kohl was Chancellor for 16 years. This was the longest time any German chancellor had served since Otto von Bismarck. During his time in office, major events happened. These included the end of the Cold War, the German reunification (when East and West Germany became one country again), and the creation of the European Union (EU).

Born in Ludwigshafen to a Catholic family, Kohl joined the CDU party when he was 16 years old in 1946. He studied history at Heidelberg University and earned a special degree called a PhD in 1958. Before becoming a full-time politician, he worked in business.

In 1959, he became the youngest member of the state parliament in Rhineland-Palatinate. From 1969 to 1976, he was the minister president (like a state governor) of Rhineland-Palatinate. In 1973, he became the national leader of the CDU party.

In 1982, Kohl became Chancellor through a special vote in parliament. He formed a government with another party, the FDP. As Chancellor, Kohl strongly believed in European integration, which means countries in Europe working closely together. He also had a very good relationship with France. He was a strong friend of the United States and supported its policies against the Soviet Union.

After the Revolutions of 1989 (when communist governments in Eastern Europe fell), Kohl's government worked quickly to reunite Germany in 1990. Kohl and French President François Mitterrand were key figures in creating the Maastricht Treaty. This treaty officially established the European Union and the Euro currency. Kohl also helped expand the EU to include more countries in Eastern Europe. He played an important role in ending the Bosnian War.

After his time as Chancellor, Kohl became an honorary chairman of the CDU in 1998. He later resigned from this role in 2000 due to a party funding issue. However, his international reputation as a great European leader remained strong. He received many awards, including the Charlemagne Prize in 1988. In 1998, he was named an Honorary Citizen of Europe by European leaders. After he passed away, he was honored with the first-ever European act of state.

Contents

Life

Early Life and Education

Helmut Kohl was born on April 3, 1930, in Ludwigshafen am Rhein. He was the third child of Hans Kohl, a veteran and civil servant, and Cäcilie Kohl. His family was conservative and Catholic.

During World War II, his older brother died as a teenage soldier. When he was ten, Kohl had to join the Deutsches Jungvolk, which was part of the Hitler Youth. At 15, just before the war ended, he was officially sworn into the Hitler Youth because it was required for all boys his age. He was also called for military service in 1945 but did not fight. He later called this the "mercy of late birth," meaning he was too young to be involved in the war's worst parts.

Kohl went to elementary school and then high school. After finishing school in 1950, he started studying law in Frankfurt. In 1951, he moved to Heidelberg University to study history and political science. He was the first person in his family to go to university.

Before Politics

After graduating in 1956, Kohl worked as a researcher at Heidelberg University. In 1958, he earned his doctorate degree in history. His special paper was about how political parties started again in the Palatinate region after 1945.

After his studies, Kohl worked in business. First, he was an assistant at a factory in Ludwigshafen. Then, in 1960, he became a manager for a chemical industry group in Ludwigshafen.

Starting in Politics

In 1946, Kohl joined the newly formed CDU party. He became a full member when he turned 18 in 1948. In 1947, he helped start the youth group of the CDU in Ludwigshafen.

In 1959, Kohl was elected as the youngest member of the state parliament in Rhineland-Palatinate. In 1960, he was also elected to the local council in Ludwigshafen. He led the CDU party there until 1969.

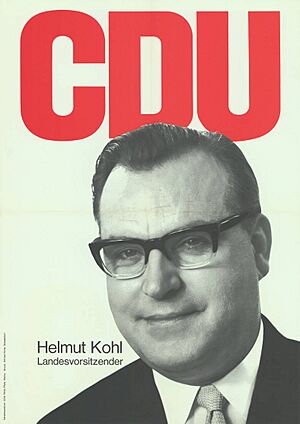

In 1963, he became the leader of the CDU group in the state parliament. In 1966, he was elected chairman of the CDU party in Rhineland-Palatinate.

Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate

Kohl became the minister-president (state governor) of Rhineland-Palatinate on May 19, 1969. He was the youngest person ever to lead a German state government. Soon after, he also became a vice-chairman of the national CDU party.

As minister-president, Kohl brought many changes, especially in schools and education. His government ended physical punishment in schools and changed how religious schools worked. He also founded the University of Trier-Kaiserslautern. He reorganized the state's districts and laws.

Becoming National Party Leader

Kohl joined the national board of the CDU in 1964. After the CDU lost the federal election in 1969, Kohl was elected to the party's executive committee. He pushed for reforms within the party, supporting more modern ideas in education and social policies.

In 1971, Kohl ran for party chairman but lost. However, after the CDU lost another election in 1972, the path was clear for Kohl. On June 12, 1973, he became the chairman of the CDU party. He remained chairman until 1998.

In 1974, when Chancellor Willy Brandt resigned, Kohl asked his party not to celebrate their opponent's difficulties. He wanted them to focus on serious politics.

First Try for Chancellor

In 1975, Kohl faced re-election in Rhineland-Palatinate. This was important because the CDU and its sister party, the CSU, were deciding who would run for chancellor in the next federal election. Kohl's party won a strong 53.9% of the vote in the state election. This helped make his position stronger.

On May 12, 1975, the CDU officially nominated Kohl as their candidate for chancellor. In the 1976 West German federal election, the CDU/CSU did very well, winning 48.6% of the votes. However, they did not form the government. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) formed a government led by Helmut Schmidt. After this, Kohl left his role as minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate to become the leader of the CDU/CSU in the national parliament, the Bundestag.

Leader of the Opposition

In the 1980 German federal election, Kohl was not the main candidate for chancellor. Instead, Franz Josef Strauß, the leader of the CSU, ran. Strauß also failed to defeat the SPD and FDP government. Kohl remained the leader of the opposition.

In September 1982, the SPD and FDP government had disagreements over economic policy. The FDP decided to leave the government and began talking with the CDU/CSU about forming a new one.

Chancellor of Germany, 1982–1998

|

|

|

Chancellorship of Helmut Kohl

|

|

|---|---|

| 1 October 1982 – 27 October 1998 | |

| Cabinet |

|

| Party | Christian Democratic Union |

| Election |

|

| Appointer |

|

| Nominator | Bundestag |

| Seat | Palais Schaumburg |

Becoming Chancellor

On October 1, 1982, the CDU, with support from the FDP, held a special vote in parliament. This vote removed the old chancellor and elected Helmut Kohl as the new Chancellor. Three days later, a new government was formed with Kohl as its leader.

This change was a bit controversial because the FDP had campaigned with the SPD in the previous election. To make sure the new government had strong public support, Kohl called for new elections very soon. He intentionally lost a confidence vote in parliament so that the president could dissolve the Bundestag and call for new elections. This move was allowed by the German court.

First Years as Chancellor (1983–1987)

In the federal elections of March 1983, Kohl won a big victory. The CDU/CSU got 48.8% of the votes, and the FDP got 7.0%. Kohl's new government made some important decisions. One was allowing NATO to place medium-range missiles in Germany, which faced a lot of opposition from peace groups.

On September 22, 1984, Kohl met with French President François Mitterrand at Verdun. This was a place where a famous battle between France and Germany happened during World War I. They shook hands, and this moment became a powerful symbol of friendship between the two countries. Kohl and Mitterrand became close political partners, which helped a lot with European integration. They started projects like Eurocorps (a European army corps) and Arte (a European TV channel).

In 1985, Kohl and U.S. President Ronald Reagan visited the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and a German military cemetery at Bitburg. This visit was meant to show the strong friendship between Germany and the U.S. However, it caused some controversy because the cemetery had graves of SS soldiers.

Policies at Home

During Kohl's time as Chancellor, several new social policies were introduced. Unemployment benefits were extended for older people. A child-rearing allowance was created to help parents. People who cared for others informally received support and tax benefits. An early retirement plan was also introduced to encourage older workers to retire and make way for unemployed people.

However, some decisions were controversial. Student aid became something that had to be paid back to the state. A health care reform in 1989 made patients pay for some services upfront and then get reimbursed. It also increased how much patients had to pay for hospital stays and medicines.

Second Term (1987–1991)

After the 1987 West German federal election, Kohl won with a slightly smaller majority and formed his third government. In 1987, Kohl hosted East German leader Erich Honecker. This was the first time an East German head of state visited West Germany. This showed that Kohl continued a policy of improving relations between East and West, which had started in the 1970s.

Road to Reunification

When the Berlin Wall fell and the East German communist government collapsed in 1989, Kohl's handling of the situation became a major turning point. Kohl quickly moved to make German unity a reality. He presented a ten-point plan for "Overcoming the division of Germany and Europe" without first talking to his partners or allies.

In February 1990, he visited the Soviet Union. He wanted to get a promise from Mikhail Gorbachev that the USSR would allow Germany to reunite. One month later, the East German counterpart of Kohl's CDU won the election in East Germany, supporting quick reunification.

On May 18, 1990, Kohl signed an economic and social union treaty with East Germany. This treaty meant that when reunification happened, it would be a faster process. This was important because East Germany was in a state of collapse.

Kohl and Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher worked to get approval from the World War II allies for German reunification. Gorbachev assured Kohl that a reunited Germany could choose its international alliances. Kohl wanted Germany to remain part of NATO and the European Community.

A reunification treaty was signed on August 31, 1990. Both parliaments approved it on September 20, 1990. On October 3, 1990, East Germany officially joined West Germany. The five states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia were formed. East and West Berlin became one city-state and the capital of the new Germany.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Kohl confirmed that former German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line were now part of Poland. He signed a treaty on November 14, 1990, in Warsaw. Earlier, Kohl had caused a diplomatic issue by suggesting Germany might not accept this border. However, he later changed his stance and assured other countries that a united Germany would accept the border. In 1993, Kohl also confirmed that Germany would not claim territories from the Czech Republic.

After Reunification (1990–1998)

Reunification made Kohl very popular. In the 1990 German federal election, the first all-German elections since the Weimar Republic, Kohl won by a large margin. He then formed his fourth government.

After the 1994 German federal election, Kohl was reelected, but with a smaller majority. The SPD party gained more power in the Bundesrat (the upper house of parliament), which limited Kohl's power. In foreign policy, Kohl was successful. For example, he helped make Frankfurt am Main the home of the European Central Bank. In 1997, he received an award for his work in uniting Europe.

By the late 1990s, Kohl's popularity had decreased because unemployment was rising. In the 1998 German federal election, he lost to Gerhard Schröder. The future Chancellor Angela Merkel started her political career as Kohl's protégé. In 1991, he appointed her to his government, helping her become well-known.

Retirement

A new government led by Gerhard Schröder took over on October 27, 1998. Kohl immediately resigned as CDU leader and mostly retired from politics. He remained a member of the Bundestag until 2002, when he decided not to run for re-election.

Party Funding Issue (1999–2000)

After leaving office, Kohl faced a scandal about party funding. It was discovered in 1999 that the CDU had received and kept illegal donations while Kohl was its leader. While it was never suggested that Kohl personally benefited, he was criticized for managing the party's finances outside of legal rules, such as using secret bank accounts. This damaged his reputation in Germany. However, outside of Germany, he was still seen as a great European statesman, remembered for his role in German reunification, European integration, and relations with Russia.

Life After Politics

In 2002, Kohl left parliament and officially retired. Later, his party largely supported him again. Angela Merkel, after becoming Chancellor, invited him to her office. In 2004, he published the first part of his memoirs, covering his life until he became chancellor in 1982. The second part, published in 2005, covered the first half of his time as chancellor.

In late February 2008, Kohl had a stroke and a fall, which caused serious head injuries. He then used a wheelchair and had difficulty speaking. While in the hospital, he married Maike Kohl-Richter in May 2008. He had further health issues, including heart surgery in 2012.

In 2011, despite his health, Kohl gave interviews where he criticized Angela Merkel's policies on Europe's debt crisis and relations with Russia. He felt her policies were against his ideas of peaceful European integration. He published a book called Aus Sorge um Europa ("Out of Concern for Europe") about these criticisms.

In 2016, Kohl sued his former ghostwriter and co-author for publishing comments he allegedly made without his permission. In 2017, a German court ordered them to pay Kohl a large sum for violating his privacy.

Political Views

Kohl strongly believed in European integration and had a close relationship with French President François Mitterrand. He also worked hard for German reunification. While he continued the policy of improving relations with Eastern countries, he supported Ronald Reagan's strong policies to weaken the Soviet Union. He had a difficult relationship with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, but he shared his reunification plans with her to ease her concerns.

Personality

Kohl faced strong opposition from the political left in West Germany. Some people made fun of his appearance, his simple language, and his local accent. He was sometimes drawn as a "pear" in satirical magazines, and this became a nickname for him. Comedians also imitated him.

When Kohl was minister-president, he was seen as a young reformer. But when he became the national party leader in 1973, this changed. Some journalists and opponents doubted if he was the right person to lead the country.

Kohl was not known for being charismatic or good with the media. His speeches were often long. He was a Catholic from the Palatinate region, and some journalists from Northern Germany felt he was different from previous leaders.

However, Kohl was good at connecting with people in small groups. He had an amazing memory for people and their lives, which helped him build strong relationships within his party and abroad. He invested a lot of time in personal connections, even with less important members of parliament and local party officials. This helped him gain loyalty and affection from his supporters. He could also be tough with his staff and political opponents.

Personal Life

Family

On June 27, 1960, Kohl married Hannelore Renner. They had known each other since 1948. They had two sons, Walter Kohl (born 1963) and Peter Kohl (born 1965). Hannelore Kohl spoke French and English and was an important adviser to her husband, especially on world affairs. She strongly supported German reunification and Germany's alliance with the United States.

Both sons studied in the United States. Walter Kohl worked as a financial analyst and later started a consulting firm with his father. Peter Kohl worked as an investment banker in London. Walter Kohl has a son named Johannes. Peter Kohl is married to Elif Sözen-Kohl and they have a daughter, Leyla.

Hannelore Kohl passed away on July 5, 2001.

| Helmut Kohl Chancellor of Germany |

Hannelore Kohl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Christine Volkmann | Walter Kohl | Kyung-Sook Kohl | Peter Kohl | Elif Sözen-Kohl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Johannes Volkmann | Leyla Sözen-Kohl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Second Marriage

In 2008, while in the hospital after his head injury, Kohl married Maike Kohl-Richter. She was a former employee from his time as Chancellor. They did not have children. During this marriage, Kohl had a brain injury, could barely speak, and used a wheelchair.

Kohl's sons and former friends criticized this marriage. His sons said their father was kept "like a prisoner" by his new wife. His children and grandchildren were also prevented from seeing him for the last six years of his life. After Kohl's death, his new wife prevented his sons and grandchildren from entering his house, which was their childhood home.

Honors and Awards

Helmut Kohl received many awards and honors. He was given honorary doctorates and citizenships. He shared the Charlemagne Prize with French President François Mitterrand for their work on French-German friendship and European unity. In 1996, he received the Prince of Asturias Award.

In 1998, European leaders named Kohl an Honorary Citizen of Europe. This was for his amazing work for European integration and cooperation. He was only the second person to receive this honor. After leaving office, he received Germany's highest honor, the Grand Cross in Special Design of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. In 1999, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Death and Funeral

Helmut Kohl passed away on June 16, 2017, in his hometown of Ludwigshafen, at the age of 87. He died of natural causes.

Kohl was honored with a special European act of state on July 1 in Strasbourg, France. This was the first time such an event was held for a European leader. A Catholic church service was also held in Speyer Cathedral. Kohl was buried in the Cathedral Chapter Cemetery in Speyer. It was reported that Kohl himself chose this burial place in 2015.

No members of Kohl's family (his children and grandchildren) attended the ceremonies. This was due to disagreements with his second wife, Maike Kohl-Richter. She had prevented them from visiting him at his home and ignored their wishes for the funeral arrangements.

Tributes

Many world leaders paid tribute to Helmut Kohl after his death. Chancellor Angela Merkel said Kohl was "great in every sense of the word." She praised his "supreme art of statesmanship in the service of people and peace." Pope Francis called Kohl "a great statesman and committed European." The 14th Dalai Lama described Kohl as "a visionary leader and statesman." Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, called Kohl "my mentor, my friend, the very essence of Europe." Former U.S. President George H. W. Bush called Kohl "a true friend of freedom" and "one of the greatest leaders in post-War Europe." Former U.S. President Bill Clinton said he was "deeply saddened" by the death of "my dear friend" whose "visionary leadership prepared Germany and all of Europe for the 21st century." French President Emmanuel Macron called Kohl a "great European" and "an architect of united Germany and Franco-German friendship." Former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev said it was "real luck" that leaders like Kohl were in charge during the difficult time of 1989–1990. He said Kohl's name would be remembered by Germans and all Europeans. Russian President Vladimir Putin said he admired Kohl's "wisdom and the ability to make well-considered, far-reaching decisions." NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg called Kohl "a true European" and the "embodiment of a united Germany in a united Europe."

See also

In Spanish: Helmut Kohl para niños

In Spanish: Helmut Kohl para niños

- First Kohl cabinet

- Second Kohl cabinet

- Third Kohl cabinet

- Fourth Kohl cabinet

- Fifth Kohl cabinet

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |