Otto von Bismarck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Otto von Bismarck

Prince of Bismarck

|

|

|---|---|

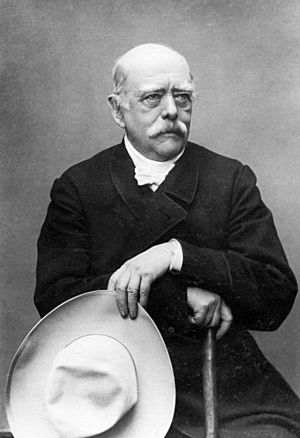

Bismarck in 1890

|

|

| Chancellor of the German Empire | |

| In office 21 March 1871 – 20 March 1890 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Deputy |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Leo von Caprivi |

| Federal Chancellor of the North German Confederation | |

| In office 1 July 1867 – 21 March 1871 |

|

| President | Wilhelm I |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Chancellor of the German Empire) |

| Minister-President of Prussia | |

| In office 9 November 1873 – 20 March 1890 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Preceded by | Albrecht von Roon |

| Succeeded by | Leo von Caprivi |

| In office 23 September 1862 – 1 January 1873 |

|

| Monarch | Wilhelm I |

| Preceded by | Adolf zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen |

| Succeeded by | Albrecht von Roon |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 23 November 1862 – 20 March 1890 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Albrecht von Bernstorff |

| Succeeded by | Leo von Caprivi |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen

1 April 1815 Schönhausen, Saxony, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 30 July 1898 (aged 83) Friedrichsruh, Aumühle, Schleswig-Holstein, German Empire |

| Resting place | Bismarck Mausoleum 53°31′38″N 10°20′9.96″E / 53.52722°N 10.3361000°E |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

Johanna von Puttkamer

(m. 1847; died 1894) |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Imperial German Army Landwehr |

| Rank | Colonel General with the rank of Field Marshal |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite with oak leaves |

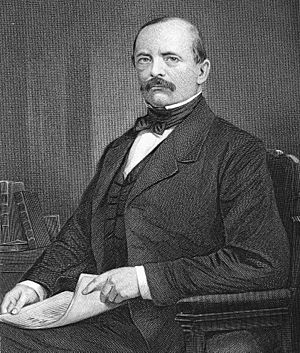

Otto von Bismarck (born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, April 1, 1815 – July 30, 1898) was a very important German leader. He was a statesman and diplomat from Prussia. Bismarck came from a wealthy family of landowners called Junkers. He quickly became powerful in Prussian politics.

From 1862 to 1890, he was the Minister-President and foreign minister of Prussia. Before that, he was an ambassador to Russia and France. Bismarck is most famous for bringing the many German states together to form the German Empire in 1871. He then became the first Chancellor of the German Empire and was a major player in European politics until 1890.

Bismarck worked closely with King Wilhelm I of Prussia to unite Germany. This partnership lasted for Wilhelm's entire life. King Wilhelm gave Bismarck the titles of Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen in 1865 and Prince of Bismarck in 1871. Bismarck started three short, but important wars against Denmark, Austria, and France. After defeating Austria, he created the North German Confederation. This was the first German national state, bringing the smaller North German states together with Prussia.

After defeating France, with the help of the South German states, he formed the German Empire. This new empire did not include Austria. By 1871, Prussia was the strongest power. Bismarck then used clever diplomacy to keep peace in Europe and maintain Germany's strong position. He was known for his Realpolitik, which means making decisions based on what is practical and useful, rather than on ideals. This earned him the nickname Iron Chancellor.

Bismarck also created the world's first welfare state. This was a system of social support to help workers. He did this to gain support from the working class, who might otherwise have supported his socialist opponents. He also had a big conflict with the Catholic Church, called the Kulturkampf ("culture struggle"). He eventually stopped this struggle and worked with the Catholic Centre Party to fight the Socialists.

Bismarck was a strong and outspoken person. He could also be charming and witty. He sometimes pretended to have a bad temper to get what he wanted. He often threatened to resign, which usually made King Wilhelm I agree with him. Bismarck had a long-term vision for Germany and Europe. He is seen as a hero by many German nationalists who built many monuments to honor him. Historians praise him for uniting Germany and keeping peace in Europe through smart diplomacy.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Otto von Bismarck was born in 1815 at Schönhausen, a family estate in Prussian Saxony. His father, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Bismarck, was a Junker estate owner and a former Prussian military officer. His mother, Wilhelmine Luise Mencken, was well-educated. In 1816, his family moved to their estate in Pomerania. Bismarck spent his childhood there.

Bismarck had an older brother, Bernhard, and a younger sister, Malwine. Many people thought Bismarck was a typical country Junker, and he often dressed in military uniforms. However, he was very well-educated and knew many languages, including English, French, Italian, Polish, and Russian.

School and University Years

Bismarck went to elementary school and two secondary schools. From 1832 to 1833, he studied law at the University of Göttingen. He then went to the University of Berlin from 1833 to 1835. In 1838, he studied agriculture at the University of Greifswald while serving as an army reservist.

At Göttingen, Bismarck became friends with an American student named John Lothrop Motley. Motley later became a famous historian and diplomat. He described Bismarck as a very gifted and charming young man.

Early Career and Family Life

Bismarck wanted to become a diplomat. He started training as a lawyer in Aachen and Potsdam. However, he soon resigned. In 1838, Bismarck began his military service in the Prussian Army. After that, he returned to manage his family's estates at Schönhausen when his mother passed away.

Around age 30, Bismarck became close friends with Marie von Thadden-Trieglaff. After her death, Bismarck asked to marry Marie's cousin, Johanna von Puttkamer. They married on July 28, 1847. Their marriage was long and happy, and they had three children: Marie, Herbert, and Wilhelm.

Early Political Career

Becoming a Politician

In 1847, when he was 32, Bismarck was chosen to represent his area in the new Prussian legislature. He quickly became known as a strong supporter of the King and traditional ways. He believed the monarch had a divine right to rule.

In March 1848, a revolution broke out in Prussia. King Frederick William IV initially wanted to use force to stop it. However, he later offered some changes to the liberals, like promising a constitution. Bismarck tried to gather peasants to support the King. He also tried to get the King's brother, Prince Wilhelm, to take the throne.

The liberal movement eventually failed by the end of 1848. Conservatives regained control. In 1849, Bismarck was elected to the Landtag, the lower house of the new Prussian legislature. At this time, he was against the idea of a unified Germany. He thought Prussia would lose its independence.

Diplomat in Frankfurt

In 1851, King Frederick William IV appointed Bismarck as Prussia's representative to the Diet of the German Confederation in Frankfurt. Here, Bismarck became more practical in his political views. He realized that Prussia needed to work with other German states to balance Austria's power. He slowly began to accept the idea of a united German nation. He believed that conservatives should lead this effort.

Bismarck also worked to stay friends with Russia and have a good relationship with Napoleon III's France. This was important to challenge Austria and prevent France from allying with Russia.

Ambassador to Russia and France

In 1857, King Frederick William IV suffered a stroke, and his brother Wilhelm became Regent. Wilhelm sent Bismarck to be Prussia's ambassador to Russia. This was a promotion, but it also kept Bismarck away from German politics.

Bismarck stayed in St. Petersburg for four years. During this time, he met Alexander Gorchakov, who would later be his rival. The Regent also appointed Helmuth von Moltke as Chief of Staff of the Prussian Army and Albrecht von Roon as Minister of War. Over the next 12 years, these three men would change Prussia.

Even though he was abroad, Bismarck stayed informed about German affairs through Roon. In May 1862, he became ambassador to France. He also visited England that summer. These trips allowed him to meet important leaders like Napoleon III, Prime Minister Palmerston, and Benjamin Disraeli.

Minister President of Prussia

When King Frederick Wilhelm IV died in 1861, his brother Wilhelm became King of Prussia. King Wilhelm I often disagreed with the liberal Prussian Parliament. In 1862, a crisis happened when the Parliament refused to approve money for army changes. The King's ministers couldn't get the budget passed. King Wilhelm I considered stepping down, but his son, Crown Prince Frederick William, believed Bismarck was the only one who could solve the problem.

On September 23, 1862, King Wilhelm I appointed Bismarck as Minister-President and Foreign Minister. Bismarck, Roon, and Moltke took charge. They restructured the balance of power in Europe by creating the German Empire. This was done through Bismarck's diplomacy, Roon's army reforms, and Moltke's military plans.

Bismarck quickly gained strong influence over the King. He was determined to keep the King's power strong. He argued that since the constitution didn't say what to do if the budget wasn't approved, he could just use the previous year's budget. So, taxes continued to be collected for four years without Parliament's approval.

"Blood and Iron" Speech

German unification was a big goal of the 1848 revolutions. Representatives from German states met in Frankfurt and tried to create a unified nation. They offered the title of Emperor to King Frederick William IV, but he refused. This attempt at unification failed for the liberals.

Bismarck believed that important changes would not happen through speeches or votes. In 1862, he famously said in a speech that the great questions of the day would be decided not by "speeches and majority resolutions" but by "blood and iron"—meaning military force. This showed his belief that war and military strength would be necessary to achieve Germany's goals.

Defeating Denmark and Austria

Before the 1860s, Germany was made up of many small states. Bismarck used both diplomacy and the Prussian military to unite them. He made sure Austria was not part of this unified Germany. This made Prussia the most powerful part of the new Germany.

In 1863, a problem arose over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Both Denmark and a Danish duke claimed them. Bismarck insisted the territories belonged to the Danish King under an old agreement. However, he was against Denmark fully taking Schleswig. With Austria's help, Prussia demanded Denmark return Schleswig to its old status. When Denmark refused, Austria and Prussia invaded, starting the Second Schleswig War. Denmark lost and had to give up both duchies.

Bismarck then made a deal with Austria called the Gastein Convention. Prussia got Schleswig, and Austria got Holstein. In 1865, Bismarck was given the title of Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen.

In 1866, Austria broke the agreement, and Bismarck used this as an excuse to start a war with Austria. He sent Prussian troops to take Holstein. Other German states joined Austria in the Austro-Prussian War. Thanks to Roon's army reforms and Moltke's military plans, the Prussian army was strong. Bismarck also made a secret alliance with Italy, which wanted land from Austria. Italy's involvement forced Austria to divide its forces.

The war lasted only seven weeks. Prussia won a major victory at the Battle of Königgrätz. King Wilhelm and his generals wanted to march on Vienna, but Bismarck convinced them to make a "soft peace." He wanted to quickly restore friendly relations with Austria.

As a result of the Peace of Prague (1866), the German Confederation was dissolved. Prussia took over Schleswig, Holstein, and several other states. Austria also promised not to interfere in German affairs. To strengthen Prussia's power, Bismarck formed the North German Confederation in 1867. This new confederation included 21 states north of the River Main. Bismarck largely wrote its constitution. King Wilhelm of Prussia became its president, and Bismarck was appointed Chancellor.

Bismarck gained huge political support in Prussia after this military success. In the 1866 elections, liberals lost their majority in Parliament. The new, more conservative Parliament approved the budgets from the past four years, which Bismarck had implemented without their consent.

Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871)

Prussia's victory over Austria increased tensions with France. The French Emperor, Napoleon III, wanted to gain territory as compensation for not joining the war against Prussia. Bismarck did not avoid war with France, but he feared that Austria or Russia might ally with France. He believed that if the German states saw France as the aggressor, they would unite behind Prussia.

A reason for war came in 1870 when a German prince was offered the Spanish throne. France pressured him to withdraw his offer. Not satisfied, France demanded that King Wilhelm promise no Hohenzollern would ever seek the Spanish crown again. To provoke France, Bismarck published the Ems Dispatch. This was a carefully edited version of a conversation between King Wilhelm and the French ambassador. The editing made each side feel insulted, leading to strong feelings for war.

France declared war on July 19. The German states saw France as the aggressor and united with Prussia. Bismarck's two sons served as officers in the Prussian cavalry. The German army, led by Moltke, won many victories. Napoleon III was captured at Sedan. The war ended with a siege of Paris.

Unifying Germany

Bismarck quickly worked to unite Germany. He negotiated with the southern German states, offering them special deals if they joined. These talks were successful, as patriotic feelings were very strong. While the war was still going on, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was declared German Emperor on January 18, 1871. This happened in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.

The new German Empire was a federation. Each of its 25 states kept some independence. The King of Prussia, as German Emperor, was the "first among equals." He led the Bundesrat, which discussed policies presented by the Chancellor.

France had to give up Alsace and part of Lorraine. This was because Moltke and his generals wanted it as a buffer zone. France also had to pay a large sum of money. Historians still debate whether Bismarck planned all these events or simply reacted to opportunities. However, his actions led to the creation of a powerful, unified Germany.

Chancellor of the German Empire

In 1871, Bismarck was given the title of Fürst (Prince). He was also appointed the first Imperial Chancellor (Reichskanzler) of the German Empire. He kept his Prussian jobs, like Minister-President and Foreign Minister. This gave him almost complete control over Germany's policies. In 1873, the job of Minister-President of Prussia was briefly separated, but Bismarck took it back by the end of the year.

The Kulturkampf (Culture Struggle)

Bismarck started a conflict with the Catholic Church in Prussia in 1871, called the Kulturkampf ("culture struggle"). He worried that the Pope and the Catholic Church had too much political power in Germany. He was also concerned about the rise of the Catholic Centre Party.

With support from the National Liberal Party, Bismarck removed the Catholic Department from the Prussian Ministry of Culture. This meant Catholics had no voice in high government circles. In 1872, the Jesuits were expelled from Germany. More anti-Catholic laws followed, allowing the government to control the education of Catholic clergy. In 1875, civil weddings became required, meaning church weddings alone were no longer legally recognized.

The Kulturkampf made Catholics organize and strengthen the Centre Party. Bismarck, a devout Protestant, became worried that secularists and socialists were using this struggle to attack all religions. He stopped the Kulturkampf in 1878 because he needed the Centre Party's support for his new fight against socialism. The new Pope, Pope Leo XIII, was more open to negotiation. Most anti-Catholic laws were removed, and Catholics largely supported German unification and Bismarck's policies.

Economy and Tariffs

In 1873, Germany and much of Europe faced an economic downturn called the Long Depression. To help struggling industries, Bismarck stopped free trade and introduced protectionist import-tariffs. This upset the National Liberals, who supported free trade.

Bismarck used the public's unhappiness with the Kulturkampf to distance himself from the National Liberals. By 1879, his close ties with them ended. He then turned to conservative groups, including the Centre Party, for support. He gained their support by putting in place tariffs to protect German agriculture and industry from foreign competition.

Policies Against Socialism

Bismarck was worried about the growing socialist movement and the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Since the SDP was protected by the constitution, Bismarck tried to weaken it without banning it completely. In 1878, he introduced Anti-Socialist Laws. These laws banned socialist organizations and meetings, outlawed trade unions, closed newspapers, and stopped the spread of socialist writings.

Despite these laws, the SDP continued to gain supporters and seats in the Reichstag. Bismarck also tried to win over working-class people by introducing social benefits. These included accident insurance, old-age insurance, and a form of socialized medicine. He called this "practical Christianity." He hoped these programs would make workers more loyal to the government and less likely to support socialists.

However, Bismarck did not completely succeed in stopping socialism. Support for the SDP continued to grow with each election.

Foreign Policies and Alliances

Bismarck was very skilled in diplomacy. He carefully studied the interests of other countries. This helped him avoid misunderstandings and find ways for Germany to work with other nations. He believed that diplomacy should be based on facts and calculations, not emotions.

After Germany was unified in 1871, Bismarck focused on keeping peace in Europe. He knew that France wanted revenge for losing Alsace and Lorraine. So, Bismarck worked to isolate France diplomatically. He kept good relationships with other European countries. He wasn't interested in colonies or a large navy, which helped him avoid conflicts with Great Britain.

Historians say Bismarck did not want any more territory after 1871. He worked hard to create a system of alliances that would prevent war in Europe. By 1878, he was seen as a champion of peace.

Bismarck feared that Austria, France, and Russia might team up against Germany. His solution was to ally with two of them. In 1873, he formed the League of the Three Emperors. This alliance included Wilhelm I, Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and Emperor Francis Joseph of Austria-Hungary. They aimed to control Eastern Europe and keep ethnic groups in check.

France was Bismarck's main challenge. Peaceful relations were difficult after Germany took Alsace and Lorraine. Bismarck believed France would never forgive this, so he focused on isolating France. He encouraged other countries to view France's new republican government negatively.

Bismarck also maintained good relations with Italy. The wars he started helped Italy gain territory and unify.

After Russia defeated the Ottoman Empire in 1878, Bismarck helped negotiate a peace deal at the Congress of Berlin. This treaty reduced the size of a pro-Russian state (Bulgaria). This worsened relations between Russia and Germany. Bismarck refused calls for a war with Russia. He also tried to help Britain in Central Asia, hoping to keep Russian troops far from Germany.

Triple Alliance

When the League of the Three Emperors fell apart, Bismarck negotiated the Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary in 1879. They promised to help each other if Russia attacked. He also formed the Triple Alliance in 1882 with Austria-Hungary and Italy.

Bismarck also made a secret Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1887. This was to prevent France and Russia from surrounding Germany. Both countries promised to stay neutral if the other was attacked, unless Russia attacked Austria-Hungary. However, this treaty was not renewed after Bismarck left office.

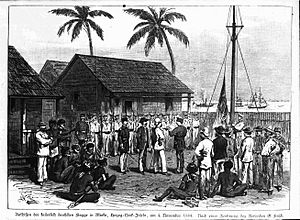

Colonies and Imperialism

Bismarck initially opposed acquiring colonies. He thought they would cost too much to get and defend, and would distract Germany from European affairs. He also believed that Germany's strict bureaucracy wouldn't work well in tropical colonies. However, in 1883–1884, he suddenly changed his mind and built an overseas empire in Africa and the South Pacific.

He was aware that the public wanted colonies for Germany's prestige. He was also influenced by merchants who wanted new markets. Other European nations were rapidly acquiring colonies, so Bismarck decided to join the Scramble for Africa.

Germany's new colonies included Togoland, German Kamerun, German East Africa, and German South-West Africa. The Berlin Conference (1884–1885), organized by Bismarck, set rules for acquiring African colonies. Germany also gained colonies in the Pacific, like German New Guinea.

Some historians argue that Bismarck's colonial policies were a way to deal with internal political and economic issues. He wanted to maintain economic growth and social stability. He also wanted to strengthen traditional power structures and avoid a major war.

Downfall and Retirement

In 1888, Kaiser Wilhelm I died. His son, Friedrich III, became emperor but was already very ill with cancer. He died after only 99 days. His son, Wilhelm II, then became emperor. Wilhelm II disagreed with Bismarck's careful foreign policy. He wanted Germany to expand quickly and have a bigger "place in the sun."

Bismarck was much older than Wilhelm II and had not expected to serve under him. Conflicts soon arose between them. Their final disagreement happened when Bismarck tried to pass strict anti-socialist laws in 1890. Wilhelm II was more interested in social problems and workers' rights. He often interrupted Bismarck in meetings to express his views.

Bismarck disagreed with Wilhelm's policies and tried to work around them. He even tried to get Wilhelm to veto the anti-socialist bill, hoping to provoke a violent clash with socialists that could be used as an excuse to crush them. Wilhelm refused, saying he wouldn't start his reign with bloodshed.

The final break came when Bismarck refused to sign a proclamation about worker protection, as required by the constitution. This was his way of protesting Wilhelm's growing interference. Bismarck also secretly tried to undermine a European labor council that Wilhelm wanted.

Bismarck resigned at Wilhelm II's request on March 18, 1890, at age 75. He was replaced by Leo von Caprivi. After his dismissal, Bismarck was given the honorary rank of "Colonel-General with the Dignity of Field Marshal" and the title of Duke of Lauenburg. He joked that the duke title would be useful for traveling secretly.

Bismarck retired to his estates and hoped to be called upon for advice, but he never was. After his wife's death in 1894, his health worsened. He became a full-time wheelchair user a year later.

Death

Bismarck spent his last years writing his memoirs, Gedanken und Erinnerungen (Thoughts and Memories). In his memoirs, he continued to criticize Wilhelm II. He also revealed the secret Reinsurance Treaty with Russia, which was a major breach of national security.

Bismarck's health declined in 1896. He died just after midnight on July 30, 1898, at age 83, in Friedrichsruh. He is buried in the Bismarck Mausoleum. His eldest son, Herbert, became Prince Bismarck. Bismarck's tombstone has the inscription: "A loyal German servant of Emperor Wilhelm I."

Bismarck's Legacy

Historians largely agree on Bismarck's importance. His achievements from 1862 to 1871 are seen as "the greatest diplomatic and political achievement by any leader in the last two centuries." Bismarck's most important legacy is the unification of Germany. Before him, Germany was a collection of hundreds of separate states. Thanks to his efforts, these states became one country.

After unification, Germany became one of Europe's most powerful nations. Bismarck's smart and careful foreign policies allowed Germany to stay strong and peaceful. He maintained friendly relations with almost all European nations. France was the main exception due to the Franco-Prussian War and Bismarck's harsh policies afterward. France became one of Germany's biggest enemies.

Bismarck believed that as long as Britain, Russia, and Italy were sure Germany wanted peace, France's hostility could be managed. However, his diplomatic system was undone by Kaiser Wilhelm II. Wilhelm II's policies eventually united other European powers against Germany, leading to World War I.

Historians note that Bismarck's peace-focused diplomacy was not popular with everyone in Germany. Many Germans wanted more expansion. Wilhelm II's desire for Germany to have a bigger global role was very different from Bismarck's approach. Also, Bismarck tried to keep the military from having too much say in foreign policy, but this changed by 1914.

Bismarck was a conservative who also brought in welfare programs. He taught conservatives to be nationalists and support social programs, which helped them gain more support. He worked with liberals, then fought Catholics, then allied with Catholics against liberals. However, some historians argue that he weakened liberalism in Germany, which had negative effects later.

Bismarck's personality has been viewed differently. Some describe him as intimidating and ruthless, using others' weaknesses. British historians see him as a very skilled leader who didn't leave a lasting system for less skilled successors. As a strong supporter of the monarchy, Bismarck didn't create strong constitutional checks on the Emperor's power. This created problems for Germany later on.

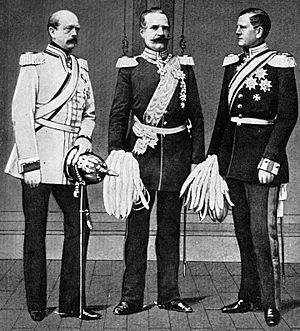

For most of his nearly 30 years in power, Bismarck had full control over government policies. He was strongly supported by his war minister, Albrecht von Roon, and the army leader, Helmuth von Moltke. Bismarck's diplomatic successes relied on a strong Prussian military, and these two men gave him the victories he needed to unite the German states.

Bismarck took steps to limit political opposition, such as restricting press freedom and passing anti-socialist laws. He fought the Catholic Church in the Kulturkampf. He later realized that Catholics were natural allies against socialists and changed his stance. Kaiser Wilhelm I rarely challenged Bismarck. Bismarck often got his way by threatening to resign. However, Wilhelm II wanted to rule himself, and removing Bismarck was one of his first goals as Kaiser. Bismarck's successors as Chancellor had much less power, as it was concentrated in the Emperor's hands.

Memorials and Memory

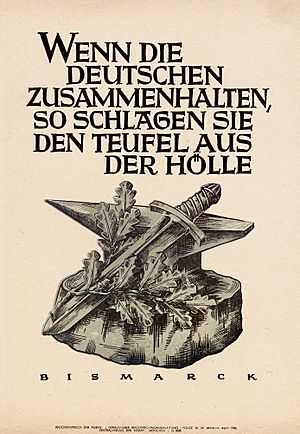

After he left office, people began to praise Bismarck. Funds were set up to build monuments and towers in his honor. Many buildings were named after him, and books about him became very popular. The first monument to him was built in Bad Kissingen in 1877.

Many statues and memorials are found across Germany. These include the famous Bismarck Memorial in Berlin and numerous Bismarck towers on four continents. The large, white Bismarck Monument in Hamburg, built in 1906, is one of the most famous memorials to him. Two warships were also named in his honor: the SMS Bismarck and the Bismarck.

Bismarck remained a very famous figure in Germany until the 1930s. He was remembered as a great hero who defeated enemies, especially France, and unified Germany into a powerful nation. However, there were other memories too. His fellow Junkers were disappointed that Prussia was absorbed into the German Empire. Liberals celebrated his creation of a unified state and the rule of law. Social Democrats and labor leaders, whom he had targeted, still saw him as an enemy. Catholics remembered the Kulturkampf and remained distrustful. Poles especially disliked his Germanization policies.

Some historians argue that the "Bismarck myth" that grew after his death made him seem like a strict nationalist. This myth was used against the Weimar Republic (Germany's first democracy) and influenced German political culture. It led Germans to seek a very strong leader, asking, "What Would Bismarck Do?"

Honors and Titles

Titles

Bismarck was given the title Graf von Bismarck-Schönhausen ("Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen") in 1865. In 1871, he became Fürst von Bismarck ("Prince of Bismarck"). In 1890, he received the title Herzog von Lauenburg ("Duke of Lauenburg"). This duchy was one of the territories Prussia took from Denmark in 1864.

Bismarck wanted his family to have the status of a sovereign duchy. He hoped to gain the privileges of a royal family for himself and his descendants. However, Kaiser Wilhelm I refused this. After Bismarck was forced to resign, he received only the honorary title of "Duke of Lauenburg," without the actual land or sovereignty. Bismarck saw this as a cruel joke by the Emperor.

Awards and Decorations

Bismarck received many honors and decorations from Germany and other countries throughout his life. These included:

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle (Prussia)

- Knight of the Black Eagle (Prussia)

- Pour le Mérite (Prussia)

- Iron Cross (1870) (Prussia)

- Knight of St. Hubert (Bavaria)

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (France)

- Knight of the Annunciation (Italy)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (Japan)

- Knight of the Golden Fleece (Spain)

- Knight of the Seraphim (Sweden-Norway)

- Knight of St. Andrew (Russia)

See also

In Spanish: Otto von Bismarck para niños

In Spanish: Otto von Bismarck para niños

- Conservatism in Germany

- House of Bismarck

- Bismarck towers

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |