Napoleon III facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Napoleon III |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, c. 1855

|

|||||

| Emperor of the French | |||||

| Reign | 2 December 1852 – 4 September 1870 | ||||

| Predecessor | Himself (as President of France) | ||||

| Successor | Adolphe Thiers (as President of France) | ||||

| Cabinet Chief | |||||

| President of France | |||||

| In office 20 December 1848 – 2 December 1852 |

|||||

| Prime Minister |

|

||||

| Vice President | Henri Georges Boulay de la Meurthe | ||||

| Predecessor | Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (as Chief of the Executive Power) | ||||

| Successor | Himself (as Emperor of the French) | ||||

| Born | 20 April 1808 Paris, First French Empire |

||||

| Died | 9 January 1873 (aged 64) Chislehurst, England |

||||

| Burial | St Michael's Abbey, Farnborough | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Louis-Napoléon, Prince Imperial | ||||

|

|||||

| House | Bonaparte | ||||

| Father | Louis Bonaparte | ||||

| Mother | Hortense de Beauharnais | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | Second French Empire | ||||

| Service/ |

|

||||

| Years of service | 1859–1870 | ||||

| Rank |

|

||||

| Unit |

|

||||

| Battles/wars |

|

||||

Napoleon III (born Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 1808 – 9 January 1873) was a very important leader in France. He was the first President of France from 1848 to 1852, and then he became the last monarch of France, ruling as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. He was the nephew of the famous Napoleon I.

In 1848, he was elected President of the Second Republic. When he couldn't be reelected by law, he took power by force in 1851. After that, he declared himself Emperor and started the Second Empire. He ruled until the French Army was defeated and he was captured by Prussia and its allies at the Battle of Sedan in 1870.

Napoleon III was a popular ruler who helped modernize France's economy. He also made Paris much more beautiful with new wide streets and parks. He expanded France's overseas territories and made the French merchant navy the second largest in the world. He was involved in wars like the Second Italian War of Independence and the very difficult Franco-Prussian War, where he was captured.

He ordered a huge rebuilding of Paris, led by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. He also made the railway system bigger and better across the country and updated the banking system. Napoleon III supported the building of the Suez Canal and improved farming methods, which stopped famines in France and helped the country export food. He also made trade agreements with other European countries, like the one with Britain in 1860. He introduced social reforms, giving French workers the right to strike and organize. He also allowed women to attend French universities.

In foreign policy, Napoleon III wanted France to be a strong influence in Europe and worldwide. He teamed up with Britain to defeat Russia in the Crimean War (1853–1856). He helped Italian unification by fighting against the Austrian Empire. In return, France gained Savoy and Nice in 1860. He also sent troops to protect the Papal States (lands ruled by the Pope) from being taken over by Italy. He helped unite the Danubian Principalities, which became modern-day Romania. Napoleon III also doubled the size of the French colonial empire in Asia, the Pacific, and Africa. However, his attempt to create an empire in Mexico failed completely.

From 1866, Napoleon III faced the growing power of Prussia, led by its Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who wanted to unite Germany. In July 1870, Napoleon III declared war on Prussia because of public pressure. The French Army was quickly defeated, and Napoleon III was captured at Sedan. He was removed from power, and the Third Republic was declared in Paris. He went to live in England, where he died in 1873.

Early Life and Family History

Childhood and Growing Up

Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, who later became known as Louis Napoleon and then Napoleon III, was born in Paris on April 20, 1808. His father was Louis Bonaparte, the younger brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. His uncle Napoleon had made Louis king of Holland. His mother was Hortense de Beauharnais, the only daughter of Napoleon's wife, Joséphine.

Joséphine, who could not have more children, suggested the marriage between Louis and Hortense so that Napoleon I could have an heir. Louis and Hortense had a difficult relationship and did not live together much. Their first son died young. Though they were separated, they had another son, and then decided to have a third child. Louis was born a bit early. Some of Louis Napoleon's enemies said he was not the son of Louis Bonaparte, but most historians today agree he was.

Charles-Louis was baptized in 1810. His uncle, Emperor Napoleon, was his godfather. When he was seven, Louis Napoleon visited his uncle in Paris and saw soldiers parading. He last saw his uncle just before Napoleon went to the Battle of Waterloo.

After Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, all members of the Bonaparte family had to leave France. Hortense and Louis Napoleon moved to Switzerland. He went to school in Germany, which gave him a slight German accent for the rest of his life. His teacher at home taught him French history and ideas about revolution.

A Young Revolutionary (1823–1835)

When Louis Napoleon was fifteen, his mother moved to Rome, Italy. He learned Italian and explored old ruins. He became friends with the French Ambassador, François-René de Chateaubriand, a famous writer.

He reunited with his older brother, Napoléon-Louis. Together, they joined the Carbonari, a secret group fighting against Austria's control of Northern Italy. In 1831, when Louis Napoleon was 23, the Austrian and papal governments attacked the Carbonari. The two brothers had to run away. During their escape, Napoléon-Louis got sick and died in his brother's arms. Hortense joined Louis Napoleon, and they managed to escape the police and the Austrian army, finally reaching the French border.

Hortense and Louis Napoleon secretly traveled to Paris. The old king, Charles X, had just been replaced by a more liberal king, Louis Philippe I. They stayed in a hotel, and Hortense asked the King if they could stay in France. Louis Napoleon even offered to join the French Army. The King secretly met Hortense and agreed they could stay briefly if they kept a low profile. Louis-Napoleon was told he could join the army if he changed his name, which he refused to do. They had to leave Paris on May 5, the tenth anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte's death, because their presence had become known, and people were gathering outside their hotel to mourn the Emperor. They went to Britain briefly, then back to Switzerland.

Early Adult Years and Political Ideas

Becoming the Bonaparte Leader

After Napoleon I fell in 1815, some people in France, called Bonapartists, wanted a Bonaparte to rule again. Napoleon I's son was first in line, but he was held captive in Vienna and died in 1832. After his death, Charles-Louis Napoleon became the main heir of the Bonaparte family and the leader of the Bonapartist cause.

While living in Switzerland, he joined the Swiss Army and trained as an officer. He also started writing about his political ideas. He believed in a government that was "strong without being a dictator, free without chaos, independent without conquering others." He published his ideas in books like Napoleonic Ideas, which were translated into many languages. He believed in giving all men the right to vote and putting the country's interests first.

Failed Attempts to Take Power (1836–1848)

Louis Napoleon believed he was meant to lead France. He thought if he marched into Paris, like Napoleon I did in 1815, the French people would support him. So, he planned a takeover against King Louis-Philippe.

His first attempt was in Strasbourg in 1836. He gathered some soldiers, but the plan failed quickly. Louis Napoleon fled back to Switzerland. King Louis-Philippe demanded that Switzerland hand him over, but Switzerland refused. Louis Napoleon then left voluntarily and traveled to London, then to Brazil, and then to New York. While in New York, he learned his mother was very ill and rushed back to Switzerland to be with her before she died in 1837. He could not attend her burial in France because he was still not allowed in the country.

Louis Napoleon returned to London in 1838. He had inherited money from his mother and lived comfortably. He met important people like Benjamin Disraeli and Michael Faraday. He also studied Britain's economy and admired Hyde Park, which later inspired his plans for Paris.

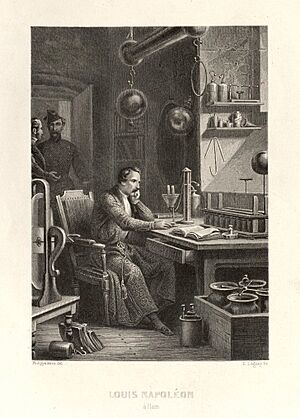

In 1840, he tried another takeover. He gathered about sixty armed men, hired a ship, and sailed to Boulogne, France. This attempt also failed badly. Customs agents stopped them, and soldiers refused to join. Louis Napoleon and his men were arrested. Newspapers made fun of him. He was sentenced to life in prison in the fortress of Ham in Northern France.

While in prison, he wrote poems, essays, and articles. He became known as a writer. His most famous book, L'extinction du pauperisme (1844), studied poverty among workers and suggested ways to end it. He believed workers should have property and good jobs. This book became very popular and helped him later.

He was unhappy in prison. He knew that Napoleon Bonaparte's popularity was growing in France. In 1840, Napoleon's remains were brought back to Paris with a huge ceremony, but Louis Napoleon could only read about it in prison. In 1846, he escaped from prison by disguising himself as a worker carrying wood. He was then taken by carriage and boat to England. A month after his escape, his father died, making Louis Napoleon the clear leader of the Bonaparte family.

Back in London, he continued his studies. He also met a wealthy woman named Harriet Howard who became his companion and helped him financially with his political plans.

Rise to Power

The 1848 Revolution and Becoming President

In February 1848, Louis Napoleon heard about a revolution in France. King Louis Philippe had to leave the country. Louis Napoleon went to Paris, where the Second Republic was declared. He wrote to the new government, saying he wanted to serve his country. He was asked to leave Paris until things were calmer, and he did.

He didn't run in the first elections for the National Assembly, but other Bonaparte family members were elected, showing the name still had power. In the next elections in June 1848, he was elected in four different areas. Many of his supporters were peasants and working-class people. His book on poverty was popular, and his name was cheered alongside socialist leaders.

The government leaders thought about arresting him, but he cleverly wrote that he would wait to return so his presence wouldn't cause problems for the Republic.

In June 1848, there was a big uprising in Paris by left-wing groups. The army crushed it, and many people were killed or arrested. Because Louis Napoleon was not in Paris, he was not linked to either the uprising or the harsh response. He was elected again in September and took his place in the National Assembly. In just seven months, he went from an exile to a powerful figure, as France prepared for its first-ever presidential election.

Winning the 1848 Presidential Election

The new constitution of the Second Republic said that the president would be elected by popular vote, meaning all men could vote. The elections were set for December 1848. Louis Napoleon quickly announced he would run. There were other candidates, including a general, a poet, and socialist leaders.

Louis Napoleon set up his campaign in Paris. His companion, Harriet Howard, gave him a large loan to help pay for his campaign. He didn't speak much in the National Assembly and wasn't a great speaker. He spoke slowly with a slight German accent. His opponents sometimes made fun of him.

His campaign appealed to many different groups. He promised to support "religion, family, property" but also to "give work to those unoccupied" and "look out for the old age of the workers." His supporters, many of them veterans of Napoleon I's army, campaigned for him across the country. Even conservative leaders supported him, thinking he would be easy to control.

The elections were held on December 10–11. Louis Napoleon won by a huge margin, getting 5,572,834 votes, or 74.2 percent of all votes. His main opponent got only 1.4 million votes. Louis Napoleon won support from peasants, unemployed workers, small business owners, and thinkers like Victor Hugo. He won in almost all parts of France.

Prince-President (1848–1851)

Louis Napoleon moved into the Élysée Palace in December 1848. He hung portraits of his mother and Napoleon I. He chose the title "Prince-President" and wore the uniform of a general.

He quickly got involved in foreign policy. He sent French troops to Italy to help the Pope, who had been overthrown by Italian republicans. This made French Catholics happy but angered republicans. To please Catholics, he approved a law that gave the Catholic Church a bigger role in French education.

In May 1849, new elections for the National Assembly were held. A group of conservative republicans, called "The Party of Order," won most seats. Socialists also did well, but moderate republicans did poorly. The Party of Order had enough power to block Louis Napoleon's plans.

In June 1849, socialists tried to take power in Paris. Louis Napoleon acted quickly, and the uprising was stopped. Many leaders were arrested or fled. The National Assembly then passed a new election law that prevented 3.5 million French voters from voting, mostly working-class people. Louis Napoleon disagreed with this law and presented himself as the protector of universal male suffrage (the right for all men to vote). He toured the country, giving speeches against the Assembly. He asked for the law to be changed, but the Assembly refused.

According to the Constitution, he had to step down at the end of his term. Louis Napoleon wanted to change the Constitution so he could run again, arguing that four years wasn't enough time to finish his plans. He traveled around the country and gained support, but the Assembly did not approve the change by the required two-thirds majority.

Taking Power: The Coup d'état (December 1851)

Louis Napoleon believed the people supported him, so he decided to stay in power by other means. His close advisors secretly planned a takeover. On the night of December 1–2, soldiers quietly took control of important buildings and newspaper offices in Paris. The next morning, Parisians saw posters announcing that the National Assembly was dissolved, universal male suffrage was restored, and new elections would be held. Many members of the National Assembly were arrested.

Some people, like writer Victor Hugo, tried to organize resistance, and a few barricades appeared in the streets. But the army quickly crushed these uprisings. There were also small uprisings in other parts of France, but these were also put down.

After the takeover, Louis Napoleon's government arrested many of his opponents, especially those from left-wing groups. About 26,000 people were arrested, and many were sent away from France. Strict rules were put on newspapers, requiring government permission to publish and allowing newspapers to be shut down after three warnings.

Louis Napoleon wanted to show that the people supported his new government. So, on December 20–21, a national vote (a plebiscite) was held asking if voters agreed to the takeover. Many mayors encouraged people to vote. Over 7.4 million people voted yes, while about 640,000 voted no. Louis Napoleon was convinced he had the public's support.

However, critics like Victor Hugo, who had supported Louis Napoleon earlier, were very angry about the takeover. Hugo left France and became a strong opponent of Napoleon III, refusing to return for twenty years.

The Second Empire Begins

A New Empire and More Power

Louis Napoleon wanted to change France from a dictatorship to a parliamentary government without another revolution. But he found himself stuck between extreme political groups. The 1851 vote also gave him the power to change the constitution. A new constitution was created in 1852, which gave Louis Napoleon unlimited 10-year terms as president. He gained absolute power to declare war, sign treaties, and start new laws. The constitution also brought back universal male suffrage but reduced the power of the National Assembly.

His government introduced new rules to control opposition. One of his first actions was to take property from the family of the late King Louis-Philippe, who had imprisoned him. Government officials were required to wear uniforms at official events. The Minister of Education could fire university professors and check their course content. University students were forbidden from growing beards, which were seen as a symbol of republicanism.

In February 1852, an election was held for a new National Assembly. The government used all its resources to support candidates who backed the Prince-President. Most votes went to official candidates. The new Assembly had only a small number of opponents.

Even with all this power, Louis Napoleon was not satisfied with being just an authoritarian president. He wanted to become Emperor. After the election, he went on a successful tour of France. In cities like Marseille, he laid the cornerstones for new buildings.

When Napoleon returned to Paris, the city was decorated with banners saying "To Napoleon III, emperor." The Senate then held another vote in November 1852 on whether to make him emperor. After a huge majority voted yes (over 7.8 million for, 253,000 against), on December 2, 1852—exactly one year after his takeover—the Second Republic officially ended. It was replaced by the Second French Empire. Prince-President Louis Napoleon Bonaparte became Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. The 1852 constitution stayed the same, but the word "president" was replaced with "emperor."

Modernizing France's Economy and Cities (1853–1869)

Building a Better France

One of Napoleon III's main goals was to modernize France's economy, which was behind countries like the United Kingdom. He believed the government should actively help the economy grow. He encouraged new banks to provide loans for businesses and government projects. He also opened French markets to foreign goods, which forced French industries to become more efficient.

The time was good for industry. Gold discoveries in California and Australia increased the money supply in Europe. New banks like Crédit Mobilier were created, selling shares to the public and lending money for big projects. By 1870, France had 20,000 kilometers of railway lines, up from only 3,500 in 1851. These railways connected French ports and other countries, carrying millions of passengers and goods.

New shipping lines were created, and ports in Marseille and Le Havre were rebuilt, connecting France by sea to many parts of the world. The number of steamships tripled, making France's merchant fleet the second largest globally by 1870. Napoleon III also supported the building of the Suez Canal between 1859 and 1869, a huge project led by a former French diplomat.

The rebuilding of Paris also helped businesses grow. The first department store, Bon Marché, opened in Paris in 1852 and grew very quickly. Other department stores like Au Printemps soon followed, becoming models for modern stores worldwide. Napoleon III's plans also included reclaiming farmland and planting new forests, like the large Landes forest in Europe.

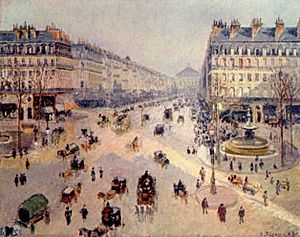

Rebuilding Paris (1854–1870)

Napoleon III started his rule by launching massive public works projects in Paris. He hired tens of thousands of workers to improve the city's sanitation, water supply, and traffic. He appointed Georges-Eugène Haussmann as the new prefect of the Seine department and gave him special powers to rebuild the city center. They planned the new Paris together.

Paris's population had doubled since 1815, but its old, narrow medieval streets were not suited for so many people. To make space, Napoleon III ordered the annexation of eleven towns around Paris in 1860, increasing the city's size and the number of its districts (arrondissements) from twelve to twenty.

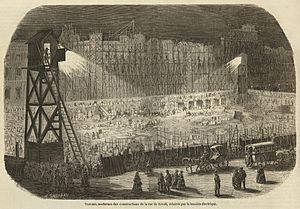

For many years, Paris was a huge construction site. New aqueducts brought clean water to the city, and hundreds of kilometers of pipes distributed it. A second network used less clean water for washing streets and watering parks. He completely rebuilt the Paris sewers and installed miles of pipes for gas streetlights.

Starting in 1854, Haussmann's workers tore down old buildings and built wide new avenues to connect key parts of the city. Buildings along these avenues had to be the same height and style, giving Paris its distinctive look.

Napoleon III also built two new railway stations: the Gare de Lyon (1855) and the Gare du Nord (1865). He finished Les Halles, a large market, and built a new hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu. The most famous new building was the Paris Opera, the largest theater in the world, designed by Charles Garnier.

Napoleon III also wanted to create new parks and gardens for Parisians to relax in. He was inspired by London's parks, especially Hyde Park. He worked with Haussmann and an engineer named Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand to create four large parks around the city: the Bois de Boulogne (west), the Bois de Vincennes (east), the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (north), and the Parc Montsouris (south). Thousands of workers dug lakes, built waterfalls, and planted trees.

He also improved older parks and created about twenty smaller parks in different neighborhoods. His goal was for everyone in Paris to be within a ten-minute walk of a park. These parks were very popular with all Parisians.

Finding an Empress

After becoming emperor, Napoleon III needed a wife to have an heir. He was still close to his companion, Harriet Howard, who attended events with him. He tried to find a royal wife, but some families declined because of his Catholic religion or concerns about his future.

Finally, Louis-Napoleon announced he had found the right woman: Eugénie du Derje de Montijo, a 23-year-old Spanish Countess. She had studied in Paris. They had a civil ceremony on January 22, 1853, and a grand church ceremony a few days later. In 1856, Eugénie gave birth to their son and heir, Napoléon, Prince Imperial.

Empress Eugénie faithfully carried out her duties, hosting guests and attending events with the Emperor. She even traveled to Egypt to open the Suez Canal and represented him when he was away. She was a strong supporter of women's equality. She pushed for the first woman in France to receive a high school diploma (baccalauréat) and tried to get a famous female writer, George Sand, elected to the French Academy.

Foreign Policy and Wars (1852–1860)

Peace and Nationalities

In a speech, Napoleon III said, "The Empire means peace," assuring other countries he wouldn't attack them to expand France. However, he was determined to have a strong foreign policy and warned he wouldn't stand by if another European power threatened its neighbors.

He also supported a new idea called "principle of nationalities," which meant creating new countries based on shared national identity, like Italy, instead of keeping old empires. He believed these new nations would become allies of France.

Alliance with Britain and the Crimean War (1853–1856)

Napoleon III wanted an alliance with Britain, where he had lived in exile. An opportunity came in 1853 when Russia put pressure on the weak Ottoman Empire. Russia wanted control over Christian lands in the Balkans and over Constantinople. The Ottoman Empire, supported by Britain and France, refused. When Russia wouldn't leave territories it had occupied, Britain and France declared war on March 27, 1854.

French and British troops landed in the Crimea and began to besiege the Russian port of Sevastopol. The siege lasted 332 days, and many soldiers died from disease. The French lost 95,000 soldiers, mostly due to illness. The suffering of the army was kept secret from the French public.

After the Russian Tsar died in 1855, his replacement, Alexander II, sought peace. Negotiations were held in Paris in 1856. The Crimean War gave France more power and respect in Europe. It was the first war between major European powers in almost half a century, showing that the old system of keeping peace was breaking down. This success encouraged Napoleon III to try an even bolder foreign policy in Italy.

Helping Italy Unite

On January 14, 1858, Napoleon and the Empress survived an assassination attempt. Bombs were thrown at their carriage, killing eight people and injuring over a hundred. The leader was an Italian nationalist named Felice Orsini, who believed killing Napoleon III would lead to a republican revolt in France that would help Italy become independent. Orsini was executed. This attack made Napoleon III focus on Italian nationalism.

Part of Italy was independent, but central Italy was ruled by the Pope, and much of the north was controlled by Austria. Napoleon III had fought with Italian patriots when he was young and sympathized with them. However, his wife, his government, and the Catholic Church in France supported the Pope and the existing Italian governments.

Count Cavour, the Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia (an independent Italian state), secretly met with Napoleon in July 1858. They agreed to work together to drive the Austrians out of Italy. In return, Napoleon III asked for Savoy and Nice, two areas that had been taken from France after Napoleon I's fall.

Napoleon III promised to send 200,000 soldiers to help Piedmont-Sardinia's 100,000 soldiers. In return, France would get Nice and Savoy if the people there agreed in a vote. The Austrian Emperor, Franz Joseph, grew impatient and invaded Piedmont in April 1859, starting the war.

War in Italy: Magenta and Solferino (1859)

Napoleon III, despite little military experience, decided to lead the French army in Italy himself. The French army crossed the Alps, and another part landed in Genoa. The Austrian commander was not aggressive, allowing the French and Piedmontese armies to unite.

The first major battle was at Magenta on June 4, 1859. It was a long and bloody fight, but the French won. The Austrians lost many men. The battle is remembered because a new bright purple dye was named "magenta" after it.

Napoleon III and King Victor Emmanuel made a triumphant entry into Milan, which had been ruled by the Austrians. The Austrians were driven from Lombardy, but their army remained in the Venice region. On June 24, the second and decisive battle was fought at Solferino. This battle was even bloodier than Magenta, with about 40,000 casualties. Napoleon III was shocked by the number of dead and wounded and quickly proposed a ceasefire, which was accepted.

Count Cavour and the Piedmontese were disappointed because Venice was still controlled by Austria, and the Pope still ruled Rome. Napoleon III returned to Paris and was celebrated. He also granted a general pardon to political prisoners and exiles.

Even without the French army, Italian unification continued. Uprisings occurred in central Italy, and Italian patriots led by Giuseppe Garibaldi took over Sicily. Napoleon III suggested the Pope give up his rebellious provinces to Victor Emmanuel, but the Pope was furious. Rome and the surrounding area remained under Papal control, and Venice was still occupied by Austrians. However, the rest of Italy came under Victor Emmanuel's rule.

As promised, Savoy and Nice became part of France in 1860 after votes, though some debated how fair these votes were. On February 18, 1861, the first Italian parliament met, and Victor Emmanuel was declared King of Italy.

Napoleon's support for Italy made him unpopular with strong French Catholics and even Empress Eugénie, who was very Catholic. To win them over, he agreed to keep French troops in Rome to protect the Pope. Garibaldi tried to capture Rome in 1862 and 1867 but was stopped by French and Papal troops. French troops stayed in Rome until August 1870, when they were called back for the Franco-Prussian War. In September 1870, Garibaldi's soldiers finally entered Rome, making it the capital of Italy.

After the Italian campaign, Napoleon III's foreign policy focused more on expanding France's influence around the world. His health began to decline, and he became less involved in daily governing.

Expanding the Overseas Empire

In 1862, Napoleon III sent troops to Mexico to try to set up a friendly monarchy there, with Archduke Maximilian of Austria as Emperor. However, the Mexican government resisted. After the American Civil War ended in 1865, the United States made it clear that France had to leave Mexico. Napoleon's army was spread thin, with troops in Mexico, Rome, and Algeria. Prussia was also becoming a threat. Napoleon realized he had to withdraw his troops from Mexico in 1866. Maximilian was overthrown and executed.

In Southeast Asia, Napoleon III was more successful. In 1862, France took control of Cochinchina (southern Vietnam, including Saigon). In 1863, he established a protectorate over Cambodia. France also gained influence in Southern China.

Life at Court and Cultural Impact

Court Life and Palaces

Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie lived in the Tuileries Palace in Paris. The Emperor's rooms were often warm and smoky because he smoked many cigarettes. The Empress's rooms were beautifully decorated.

The court moved between different palaces throughout the year. In May, they went to the Château de Saint-Cloud. In June and July, they visited the Palace of Fontainebleau for walks and boating. In July, they went to health spas like Vichy. From 1856, they spent September in Biarritz at the Villa Eugénie, a large house overlooking the sea, where they would walk, dance, and play games. In November, they moved to the Château de Compiègne for forest trips and more games. Famous scientists and artists, like Louis Pasteur and Giuseppe Verdi, were invited to these events.

At the end of the year, they returned to the Tuileries Palace for formal receptions and grand balls with hundreds of guests. Visiting leaders were often invited. During Carnival, there were elaborate costume balls.

Supporting the Arts and History

Napoleon III liked traditional art, and he commissioned famous painters like Alexandre Cabanel. However, he also supported new art. In 1863, the jury of the Paris Salon, a famous art show, rejected many works by new artists, including Édouard Manet. Artists complained, and Napoleon III decided that the rejected paintings should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry.

This exhibit, called the Salon des Refusés, attracted many visitors. While some laughed at the paintings, it was the first time the public saw these new, avant-garde works, which then became known.

Napoleon III also started or finished the restoration of many important historical buildings, led by architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. These included Notre Dame Cathedral, Mont Saint-Michel, and the medieval town of Carcassonne. He also closed a prison at Mont-Saint-Michel so it could be restored and opened to the public.

Social and Economic Changes

Social Reforms for Workers and Education

From the start of his reign, Napoleon III introduced social reforms to improve the lives of working-class people. He opened clinics for sick workers and provided legal help for those who couldn't afford it. He also supported companies that built affordable housing for workers. He made it illegal for employers to write negative comments on workers' required work documents, which had prevented them from getting other jobs. In 1866, he encouraged a state insurance fund to help disabled workers and their families.

To help the working class, Napoleon III offered a prize for an inexpensive butter substitute. This was won by a chemist who created margarine.

Workers' Rights and Education for Girls

His most important social reform was the 1864 law that gave French workers the right to strike, which had been forbidden for a long time. In 1866, he also gave factory workers the right to organize. He made rules about how apprentices should be treated and limited working hours on Sundays and holidays. He removed a law that favored employers' word over employees' in court.

Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie worked to give girls and women better access to public education. In 1861, with their help, Julie-Victoire Daubié became the first woman in France to receive the baccalauréat diploma (a high school degree). In 1862, the first professional school for young women opened, and a woman named Madeleine Brès became the first to enroll in medical school at the University of Paris.

In 1863, he appointed Victor Duruy, a respected historian, as his new Minister of Public Education. Duruy sped up reforms, often clashing with the Catholic Church, which wanted to control education. Despite the Church's opposition, Duruy opened schools for girls in many towns, totaling 800 new schools.

Between 1863 and 1869, Duruy created libraries for schools and required primary schools to teach history and geography. High schools began teaching philosophy, which had been banned. For the first time, public schools taught modern history, languages, art, and music. These reforms had a big impact: in 1852, over 40% of army recruits couldn't read or write, but by 1869, that number dropped to 25%.

At the university level, Napoleon III founded new university branches in several cities and created research institutes for sciences, history, and economics.

Economic Growth and Trade

A key part of Napoleon III's economic policy was lowering tariffs (taxes on imported goods) to open French markets. He had seen how this helped Britain. He faced strong opposition from French business owners and farmers who feared competition. But he secretly negotiated a new trade agreement with Britain in 1860, which gradually lowered tariffs in both countries. He signed it without asking the Assembly. Similar agreements were made with other European countries. This forced French industries to modernize and become more efficient, as Napoleon III intended, and trade between countries grew.

By the 1860s, the large government investments in railways, infrastructure, and financial policies had greatly changed the French economy and society. French people traveled more often and farther than ever before. The opening of public school libraries and bookstores in train stations led to more books being read across France.

During the Empire, industrial production in France increased by 73%, growing twice as fast as in the UK. Exports grew by 60% between 1855 and 1869. French farming also increased by 60% due to new techniques and markets opened by railways. The threat of famine, which had troubled France for centuries, disappeared. The last recorded famine in France was in 1855.

More people moved from the countryside to cities. The number of people working in agriculture dropped from 61% in 1851 to 54% in 1870. The average salary of French workers grew by 45%, keeping pace with rising prices. More French people were able to save money; the number of bank accounts more than doubled.

Growing Opposition and Liberal Changes (1860–1870)

Despite economic progress, opposition to Napoleon III slowly grew, especially in the French Parliament. Republicans always opposed him, believing he had wrongly taken power. Conservative Catholics were unhappy because he seemed to abandon the Pope in Italy and built a public education system that competed with Catholic schools. Many business owners were unhappy because lower tariffs meant more competition from British goods. Parliament members were also unhappy that he only consulted them when he needed money.

Napoleon's large public works and expensive foreign policy led to growing government debt. He needed to restore confidence and involve the Parliament more. In December 1861, he gave the Parliament more powers. The Senate and Assembly could now respond to his plans, ministers had to defend their programs, and deputies could suggest changes. He also allowed deputies to speak freely and published records of each session. The budget for each government department would be voted on separately, and the government could no longer spend money by special decree when Parliament was not in session.

Deputies quickly used their new rights. They criticized his Italian policy, but his proposals were still approved. In the 1863 elections, pro-government candidates still won most votes, but the opposition gained much more support, especially in Paris and other large cities. The new Assembly had a large group of opponents, from Catholics to republicans, who now had more power.

Despite this opposition in Parliament, Napoleon III's reforms remained popular in the rest of the country. In 1870, another national vote was held asking if people approved of the liberal reforms he had added to the Constitution. Napoleon III saw this as a vote on his rule. He won decisively, with over 7.3 million votes for and 1.5 million against. The leader of the republican opposition sadly wrote, "We were crushed. The Emperor is more popular than ever."

Later Years and Downfall

Declining Health and the Rise of Prussia

Throughout the 1860s, the Emperor's health got worse. His time in prison had damaged it. He had chronic pain in his legs and feet, especially in cold weather, and always kept his rooms very warm. He smoked a lot and didn't trust doctors. He walked slowly, often with a cane. His writing became hard to read, and his voice was weak. By 1870, a friend from England found him "terribly changed and very ill."

The government kept his health problems secret, fearing that if the public knew, people would demand he step down. In June 1870, doctors finally examined him and found he had gallstones, a serious condition. Before they could do much, France faced a diplomatic crisis.

In the 1860s, Prussia emerged as a new rival to France in Europe. Its leader, Otto von Bismarck, wanted Prussia to lead a unified Germany. Bismarck saw Austria and France as obstacles and planned to divide and defeat them.

Searching for Allies and War with Prussia

In 1864, when German states invaded Denmark, Napoleon III saw the threat of a unified Germany. He tried to find allies to challenge Germany but failed. Britain was suspicious of Napoleon and didn't want to get involved in European wars. Russia also didn't trust Napoleon, believing he encouraged Polish nationalists to rebel against Russian rule. Bismarck, on the other hand, had helped Russia against the Polish rebels.

In 1865, Napoleon met Bismarck. They discussed Italy, and Bismarck hinted that if France stayed neutral in a war between Austria and Prussia, France would be rewarded with some territory. Napoleon III thought of Luxembourg.

In 1866, relations between Austria and Prussia worsened. Napoleon and his foreign minister expected a long war and an Austrian victory. Napoleon III thought he could get something from both sides for France's neutrality. He secretly signed a treaty with Austria, promising French neutrality in exchange for Venice (if Austria won) and a new German state on the Rhine allied with France. At the same time, he offered Bismarck a secret treaty for French neutrality in exchange for a part of German territory. Bismarck, confident in his army, refused Napoleon's offer.

On June 15, Prussia invaded an Austrian ally. On July 3, the Prussian army crushed the Austrian army. Austria asked for a ceasefire. Prussia then took over several smaller German states. Napoleon III's health worsened again after Austria's defeat.

The Luxembourg Crisis

Napoleon III still hoped to get something from Prussia for France's neutrality. His foreign minister asked Bismarck for a region called the Palatinate and for Luxembourg to be demilitarized (no Prussian soldiers there). Napoleon's advisor even asked for Belgium and Luxembourg to be annexed by France.

The King of the Netherlands, who was also the Grand Duke of Luxembourg, was willing to sell Luxembourg to France. But Bismarck quickly stepped in and showed the British ambassador Napoleon's demands. Britain then pressured the Dutch King not to sell Luxembourg. France had to give up its claim to Luxembourg in 1867, only getting the demilitarization of the Luxembourg fortress. Napoleon III gained nothing from this.

Failure to Strengthen the French Army

Despite his poor health, Napoleon III saw that the Prussian Army, combined with other German states, would be a strong enemy. In 1866, Prussia could mobilize 700,000 men, while France had only 385,000, with many stationed overseas. In 1867, Napoleon III suggested a military service system like Prussia's to increase the French Army to 1 million men. But many French officers preferred a smaller, professional army, and the republican opposition in Parliament strongly opposed it, calling it a militarization of society. Facing defeat in Parliament, Napoleon III withdrew his proposal. A smaller plan to create a reserve force was put in place instead.

A Last Search for Allies

Napoleon III was too confident in his military strength and went to war even though he couldn't find allies to stop German unification.

After Austria's defeat, Napoleon tried to find allies against Prussia again. In 1867, he proposed an alliance with Austria, promising them territory if they joined France in a war against Prussia. But Austria was undergoing major internal changes and was not enthusiastic. Also, Napoleon's attempt to install Maximilian in Mexico had just ended badly, with French troops withdrawn and Maximilian executed.

Napoleon III also tried to persuade Italy to be his ally. The Italian King was personally open to it, remembering Napoleon's help in Italian unification. But Italian public opinion was against France because French troops had fired on Italian patriots trying to capture Rome in 1867. Italy demanded France withdraw its troops from Rome, which Napoleon III could not accept due to strong Catholic opposition in France.

Meanwhile, Bismarck signed secret military treaties with the southern German states, ensuring their troops would fight with Prussia against France. In 1868, Bismarck also made a deal with Russia, allowing Russia more freedom in the Balkans in exchange for neutrality in a war between France and Prussia. This put more pressure on Austria not to ally with France. Bismarck also reached out to Britain, offering to protect Belgium's neutrality against France. In any war between France and Prussia, France would be completely alone.

In 1867, a French politician named Adolphe Thiers criticized Napoleon III's foreign policy, saying he made "no mistake that can be made." Bismarck believed French pride would lead to war. He used this pride in the Ems Dispatch in July 1870. France declared war on Prussia, which was a huge mistake. This allowed Bismarck to present the war as defensive, even though Prussia had aggressive plans to take French territories like Alsace and Lorraine.

Defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

When France declared war, patriotic crowds in Paris sang La Marseillaise and chanted "To Berlin!" But Napoleon was sad. He told a general he expected the war to be "long and difficult" and wondered if they would come back. He felt too old for a military campaign. Despite his poor health, Napoleon decided to go to the front as commander-in-chief, as he had done in Italy. On July 28, he left Paris by train with his 14-year-old son, the Prince Imperial, and his staff. He was pale and in pain. The Empress stayed in Paris as the Regent, in charge of the government.

The French army's mobilization was chaotic. Soldiers and units couldn't find each other. The German army, led by General Moltke, was much more efficient and moved three armies to the front. German soldiers also had a large reserve force. The French army arrived at the border with maps of Germany, but not of France, where the fighting actually happened. They also had no clear plan.

On August 2, Napoleon and his son went with the army as it made a small advance into Germany near Saarbrücken. The French won a minor fight but went no further. Napoleon III, very ill, had to lean against a tree. Meanwhile, the Germans had gathered a much larger army than the French expected. On August 4, the Germans attacked a French division in Alsace at the Battle of Wissembourg, forcing them to retreat. On August 5, the Germans defeated another French Army at the Battle of Spicheren.

On August 6, 140,000 Germans attacked 35,000 French soldiers at the Battle of Wörth. The French lost many soldiers and were forced to retreat. The French fought bravely, but the Germans had better planning, communication, and leadership. Their new Krupp field guns were also much more powerful and accurate than the French cannons, causing terrible casualties.

When news of the French defeats reached Paris on August 7, people were shocked. The Prime Minister and army chief resigned. Empress Eugénie, as Regent, appointed a new government and a new military commander, Marshal François Achille Bazaine. Napoleon III realized he wasn't helping the army and wanted to return to Paris. But the Empress telegraphed him, saying, "Don't think of coming back, unless you want to unleash a terrible revolution. They will say you quit the army to flee the danger." The Emperor agreed to stay with the army, but he no longer had a real role.

On August 18, the Battle of Gravelotte, the biggest battle of the war, took place. The Germans won, and Marshal Bazaine's army of 175,000 soldiers was trapped inside the city of Metz.

Napoleon was with Marshal Patrice de MacMahon's army. The Emperor, MacMahon, Bazaine, and the Empress in Paris all had different ideas about what the army should do. Napoleon had to act as a referee. He and MacMahon wanted to move their army closer to Paris to protect the city, but Bazaine insisted they move towards Metz. Napoleon III agreed. He sent his son, the Prince Imperial, back to Paris for safety. The Emperor, riding in an open carriage, was insulted by demoralized soldiers.

The movement of MacMahon's army was supposed to be secret, but it was published in the French newspapers, so the German generals quickly knew. Moltke ordered two Prussian armies to turn towards MacMahon's army. On August 30, part of MacMahon's army was attacked and lost many men and cannons. MacMahon decided to stop and reorganize his forces at the fortified city of Sedan, near the Belgian border.

The Battle of Sedan and Surrender

The Battle of Sedan was a complete disaster for the French. MacMahon arrived at Sedan with 100,000 soldiers, unaware that two German armies were closing in, blocking any escape. The Germans arrived on August 31 and began shelling the French positions from the heights around Sedan. On September 1, MacMahon was seriously wounded. Sedan was bombarded by 700 German guns. MacMahon's replacement tried cavalry attacks to break the German encirclement, but failed. The French lost 17,000 killed or wounded and 21,000 captured.

As German shells fell, Napoleon III wandered around the French positions. An officer with him was killed. Finally, at 1 PM, Napoleon ordered a white flag to be raised. He sent a message to the Prussian King: "Monsieur my brother, not being able to die at the head of my troops, nothing remains for me but to place my sword in the hands of Your Majesty."

On September 2, Napoleon, in a general's uniform, was taken to the German headquarters. He expected to see King William but met Bismarck and General von Moltke instead. They dictated the terms of surrender. Napoleon asked for his army to be disarmed and allowed to go to Belgium, but Bismarck refused. They also asked Napoleon to sign peace treaty documents, but he refused, saying the French government in Paris would need to negotiate. The Emperor was then taken to a nearby chateau, where the Prussian King visited him. Napoleon told the King he hadn't wanted the war, but public opinion had forced him into it.

Aftermath and Exile

News of the surrender reached Paris on September 3. Empress Eugénie was shocked, refusing to believe the Emperor had surrendered. When hostile crowds gathered near the palace, she secretly left and went to England.

On September 4, a group of republican leaders in Paris declared the return of the Republic and formed a new government. The Second Empire had ended.

Captivity, Exile, and Death

From September 5, 1870, to March 19, 1871, Napoleon III and his staff were held comfortably at Schloss Wilhelmshöhe in Germany. Eugénie visited him secretly.

Marshal Bazaine, trapped with a large part of the French Army in Metz, had secret talks with Bismarck. Bazaine suggested he could establish a conservative government in France loyal to Napoleon after the Germans defeated the republic in Paris. But Bismarck lost interest in this idea as the French position weakened.

Napoleon continued to write and dreamed of returning to power. But Bonapartist candidates won only a few seats in the new National Assembly elections in February. On March 1, the new assembly officially removed the emperor from power and blamed him for France's defeat. When peace was made, Bismarck released Napoleon. The emperor decided to live in exile in England.

Napoleon, Eugénie, their son, and their staff settled at Camden Place, a large country house in England. Queen Victoria visited him there.

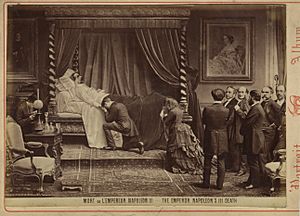

Napoleon spent his time writing and designing a more energy-efficient stove. In the summer of 1872, his health worsened. Doctors recommended surgery for his gallstones. After two operations, he became very ill. His final defeat in the war haunted him. On his deathbed, he asked his servant, "Isn't it true that we weren't cowards at Sedan?" These were his last words. He died on January 9, 1873.

Napoleon was first buried in a Catholic church in Chislehurst. After his son died in 1879 fighting in South Africa, Eugénie built a monastery and chapel for their remains. In 1888, their bodies were moved to the Imperial Crypt at St Michael's Abbey, England.

Napoleon III's Impact and Legacy

Building and Economic Achievements

Napoleon III, with Prosper Mérimée, continued to preserve many medieval buildings in France that had been neglected since the French Revolution. With Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as the main architect, many famous buildings were saved, including Notre Dame Cathedral, Mont Saint-Michel, and Carcassonne.

Napoleon III also oversaw the building of France's railway network, which helped the coal mining and steel industries grow. This greatly changed the French economy, bringing it into the modern age of large-scale business. The French economy, the second largest in the world at the time, grew very strongly under his rule. Two of France's largest banks today, Société Générale and Crédit Lyonnais, were founded during his reign. The French stock market also expanded. Historians mainly credit Napoleon for supporting the railways and helping the economy grow.

His military actions and Russia's mistakes, leading to the Crimean War, weakened the "Concert of Europe," a system that had kept peace for almost half a century. The war disrupted this peace, but the diplomatic solution showed the system still had some strength. Napoleon tried to change the map of Europe to France's advantage.

A type of cannon designed by France is still called a "Napoleon cannon" in his honor.

Historical View of Napoleon III

Napoleon III's historical reputation is not as grand as his uncle's. It was greatly damaged by France's military failures in Mexico and against Prussia. The famous writer Victor Hugo called him "Napoleon the Small," comparing him negatively to Napoleon I "The Great." In France, such strong criticism from a major writer made it hard to judge his reign fairly for a long time.

Some historians in the 1930s saw his rule as a step towards fascism, but by the 1950s, others celebrated it as an example of a modernizing government. However, historians generally view his foreign policy negatively, while his domestic policies, especially after he became more liberal after 1858, are seen more positively.

His greatest achievements were in improving France's infrastructure. He created a huge railway network that helped trade and connected the country, with Paris at its center. He is highly praised for rebuilding Paris with wide boulevards, impressive public buildings, beautiful residential areas, and large public parks like the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, which were used by everyone. He also promoted French businesses and exports. In international policy, he tried to be like his uncle, with many overseas ventures and wars in Europe. However, he handled the threat from Prussia poorly and found himself without allies against a much stronger force.

Historians also praise his concern for the working classes and poor people. His book Extinction of Pauperism, written in prison, helped him become popular among workers and contributed to his election in 1848. Throughout his reign, he worked to help the poor, sometimes going against common economic ideas of the time and using government resources to interfere in the market. For example, he gave French workers the right to strike in 1864, despite strong opposition from businesses.

Napoleon III in Films

Napoleon III has been played by several actors in movies:

- Walter Kingsford in The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936) and A Dispatch from Reuter's (1940)

- Frank Vosper in Spy of Napoleon (1936)

- Guy Bates Post in Maytime (1937) and The Mad Empress (1939)

- Leon Ames in Suez (1938)

- Claude Rains in Juarez (1939)

- Walter Franck in Bismarck (1940)

- Jerome Cowan in The Song of Bernadette (1943)

- David Bond in The Sword of Monte Cristo (1951)

- Siegfried Wischnewski in Maximilian von Mexiko (1970)

- Robert Dumont in Those Years (Spanish: Aquellos años, 1973)

- Julian Sherrier in Edward the Seventh (1975)

- Nick Jameson in The Secret Diary of Desmond Pfeiffer (1998)

- Erwin Steinhauer in Sisi (2009)

Napoleon III also has a small but important role in the animated film April and the Extraordinary World (2015).

Titles and Honors

Titles and Styles

His full title as emperor was: "Napoleon the Third, by the Grace of God and the will of the Nation, Emperor of the French".

Awards and Medals

From France

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, (1848)

- Médaille militaire, (1852)

- Commemorative medal of the 1859 Italian Campaign, (1870)

From Other Countries

Sardinia: Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 1849; Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy, 1855; Gold Medal of Military Valor, 1859

Sardinia: Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 1849; Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy, 1855; Gold Medal of Military Valor, 1859 Holy See: Grand Cross of the Order of Pope Pius IX, 1849

Holy See: Grand Cross of the Order of Pope Pius IX, 1849 Tuscany: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph, 1850

Tuscany: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph, 1850 Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, 1850

Spain: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, 1850 Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 1852

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 1852 Portugal: Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword, 1852; Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 1854; Grand Cross of the Order of St. James of the Sword, 1865

Portugal: Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword, 1852; Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 1854; Grand Cross of the Order of St. James of the Sword, 1865 Saxony: Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, 1852

Saxony: Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, 1852 Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross, 1853

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross, 1853 Bavaria: Knight of the Order of St. Hubert, 1853

Bavaria: Knight of the Order of St. Hubert, 1853- Mexico: Grand Cross of the Order of Guadalupe, 1854; Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle, 1865

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 1854

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 1854 Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1854

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1854 Austria: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, 1854

Austria: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, 1854 Two Sicilies: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit, 1854

Two Sicilies: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit, 1854 United Kingdom: Knight of the Order of the Garter, 1855

United Kingdom: Knight of the Order of the Garter, 1855 Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant, 1855

Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant, 1855 Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Military William Order, 1855

Netherlands: Grand Cross of the Military William Order, 1855 Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Order of the Seraphim, 1855; Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword, 1861

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Order of the Seraphim, 1855; Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword, 1861 Ottoman Empire: Order of the Medjidie, 1st Class, 1855; Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class, 1862

Ottoman Empire: Order of the Medjidie, 1st Class, 1855; Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class, 1862 Baden: Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1856; Grand Cross of the Order of the Zähringer Lion, 1856

Baden: Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1856; Grand Cross of the Order of the Zähringer Lion, 1856 Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 1856; Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 1856

Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 1856; Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 1856 Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Order of the Württemberg Crown, 1856

Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Order of the Württemberg Crown, 1856 Russia: Knight of the Order of St. Andrew, 1856; Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, 1856; Knight of the Order of the White Eagle, 1856; Knight of the Order of St. Anna, 1st Class, 1856

Russia: Knight of the Order of St. Andrew, 1856; Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, 1856; Knight of the Order of the White Eagle, 1856; Knight of the Order of St. Anna, 1st Class, 1856 Persia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Lion and the Sun, 1856

Persia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Lion and the Sun, 1856 Hesse-Kassel: Knight of the Order of the Golden Lion, 1858

Hesse-Kassel: Knight of the Order of the Golden Lion, 1858 Nassau: Knight of the Order of the Golden Lion of Nassau, 1858

Nassau: Knight of the Order of the Golden Lion of Nassau, 1858 Hanover: Knight of the Order of St. George, 1860; Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order

Hanover: Knight of the Order of St. George, 1860; Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order Tunisia: Husainid Family Order, 1860

Tunisia: Husainid Family Order, 1860 Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon, 1860

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon, 1860 Greece: Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer, 1863

Greece: Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer, 1863 Honduras: Grand Cross of the Order of Santa Rosa and of Civilization, 1869

Honduras: Grand Cross of the Order of Santa Rosa and of Civilization, 1869 Monaco: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Charles, 1869

Monaco: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Charles, 1869

Writings by Napoleon III

- Des Idées Napoleoniennes – a book outlining Napoleon III's ideas for France before he became Emperor.

- History of Julius Caesar – a history book he wrote during his reign, where he compared Julius Caesar's actions to his own and his uncle's.

- Napoleon III also wrote articles on military topics (like artillery), science (like electromagnetism), historical subjects, and the possibility of building the Nicaragua canal. His pamphlet The Extinction of Pauperism helped him gain political support.

Images for kids

-

Louis Bonaparte (1778–1846), the younger brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, the King of Holland, and father of Napoleon III

-

Hortense de Beauharnais (1783–1837), mother to Louis Napoleon in 1808

-

Rachel (1823–1858), a famous French actress of the time.

-

Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877), leader of the conservative republicans in the National Assembly, reluctantly supported Louis Napoleon in the 1848 elections and became his bitter opponent during the Second Republic.

-

François-Vincent Raspail, leader of the left wing of the socialist deputies in the Second Republic, who led an attempt to overthrow Louis Napoleon's government in March 1849. He was imprisoned, however Napoleon III commuted his imprisonment to an exile and he was allowed back into France in 1862

-

A caricature of Victor Hugo by Honoré Daumier from July 1849. Hugo supported Louis Napoleon in the election for president, but after the coup d'état went into exile and became his most relentless and eloquent enemy.

-

The Paris Opera was the centerpiece of Napoleon III's new Paris. The architect, Charles Garnier, described the style simply as "Napoleon the Third".

-

Napoleon III and Abdelkader El Djezairi, the Algerian military leader who led a struggle against the French invasion of Algeria

-

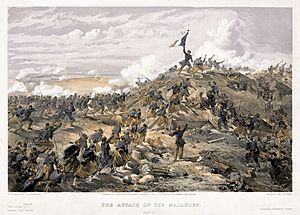

The Battle of Malakoff, 8 September 1855

-

Second French intervention in Mexico, 1861–1867

-

Napoleon III, by Gustave Le Gray, c. 1857

-

Victor Duruy, Napoléon III's Minister of Public Education from 1863 to 1869, created schools for girls in every commune of France and women were admitted for the first time to medical school and to the Sorbonne.

Error: no page names specified (help).

- Bonapartism

- Second Empire style

- Paris during the Second Empire

See also

In Spanish: Napoleón III para niños

In Spanish: Napoleón III para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |