Georges-Eugène Haussmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

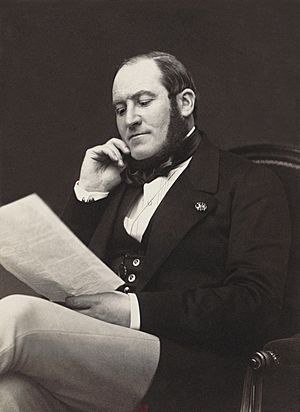

Georges-Eugène Haussmann

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies for Haute-Corse |

|

| In office 14 October 1877 – 27 October 1882 |

|

| Member of the Senate | |

| In office 9 June 1857 – 4 September 1870 |

|

| Monarch | Napoleon III |

| Prefect of Seine | |

| In office 23 June 1853 – 5 January 1870 |

|

| Monarch | Napoleon III |

| Preceded by | Jean-Jacques Berger |

| Succeeded by | Henri Chevreau |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 March 1809 Paris, France |

| Died | 11 January 1891 (aged 81) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris |

| Political party | Bonapartist |

| Spouse |

Octavie de Laharpe

(m. 1838–1890) |

| Children | Marie-Henriette Valentine Eugénie (illegitimate) |

| Education | Lycée Condorcet |

| Alma mater | Conservatoire de Paris |

| Profession | Official, prefect |

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, often known as Baron Haussmann (born March 27, 1809 – died January 11, 1891), was a French government official. He served as the prefect (a high-ranking administrator) of the Seine region, which includes Paris, from 1853 to 1870. Emperor Napoleon III chose him to lead a huge project to modernize Paris. This project involved building new wide streets called boulevards, creating beautiful parks, and improving public services. Even though some people criticized him for spending too much, his vision still shapes the look of central Paris today.

Contents

Georges-Eugène Haussmann's Life Story

Early Life and Career Beginnings

Georges-Eugène Haussmann was born in Paris on March 27, 1809. His family had German roots. His grandfather was a general under Napoleon Bonaparte and was given the title of Baron.

Haussmann went to school at Collège Henri-IV and Lycée Condorcet in Paris. He studied law but also loved music and studied at the Paris Conservatory. In 1830, he joined his father in a revolution that changed the king of France.

In 1838, he married Octavie de Laharpe. They had two daughters, Henriette and Valentine.

Haussmann started his career in government administration in 1831. He worked in different parts of France as a deputy prefect. A deputy prefect is like an assistant to the main administrator of a region. He was a hard worker, but he was also known for being a bit arrogant and bossy. This meant he wasn't promoted to the top job of prefect for a long time.

A New Opportunity

Things changed for Haussmann after the 1848 Revolution. This revolution led to the creation of the Second French Republic. Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew, became the first elected president of France.

Louis-Napoleon wanted to make big changes to Paris, like connecting the Louvre museum to the City Hall and creating a large park, the Bois de Boulogne. However, the current prefect of Paris was working too slowly.

In 1851, Louis-Napoleon became Emperor Napoleon III. He then started looking for a new prefect for Paris who could get his big plans done. After several interviews, Napoleon III chose Haussmann. On June 22, 1853, Haussmann became the prefect of the Seine. His mission was to make Paris healthier, less crowded, and more grand. He held this important job until 1870.

Remaking Paris: A Grand Project

Napoleon III and Haussmann began a massive project to rebuild Paris. They hired tens of thousands of workers. Their goal was to improve the city's sanitation, water supply, and traffic flow. Napoleon III had a large map of Paris in his office, where he marked where he wanted new boulevards to be built. These wide streets were meant to help traffic move better and connect important buildings. They also made it easier for troops to move around if needed. Napoleon III and Haussmann met almost every day to plan and solve problems.

Paris's population had doubled since 1815, but the city hadn't grown in size. To make room for more people and for those who had to move because of the new construction, Napoleon III added eleven nearby towns to Paris. This increased the number of city districts (arrondissements) from twelve to twenty, making Paris the size it is today.

For almost twenty years, Paris was a huge construction site. To bring fresh water to the city, Haussmann's engineer, Eugène Belgrand, built a new aqueduct. This increased Paris's water supply a lot. He also laid hundreds of kilometers of pipes to deliver water. A separate system used less clean water to wash streets and water the new parks. Haussmann completely rebuilt the city's sewer system and installed miles of pipes for gas streetlights.

Starting in 1854, Haussmann's teams tore down hundreds of old buildings in the city center. They built eighty kilometers of new wide avenues. Buildings along these new avenues had to be the same height and style, and faced with cream-colored stone. This gave Paris its famous uniform look. Haussmann rebuilt much of the city in just 17 years. About one-fifth of the streets in central Paris were his creation.

To connect Paris with the rest of France, Napoleon III built two new train stations: the Gare de Lyon (1855) and the Gare du Nord (1864). He also finished Les Halles, a large iron and glass market, and built a new hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu. The most famous new building was the Paris Opera, designed by Charles Garnier.

Creating Green Spaces

Napoleon III also wanted to build new parks and gardens for Parisians to relax and enjoy. He was inspired by parks in London, like Hyde Park. He worked with Haussmann and engineer Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand to create four large parks around the city.

Thousands of workers dug lakes, built waterfalls, planted lawns, flowerbeds, and trees. They also built small chalets and grottoes. These parks included the Bois de Boulogne (west), the Bois de Vincennes (east), the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (north), and Parc Montsouris (south).

Besides the large parks, Haussmann also updated older parks like Parc Monceau and the Jardin du Luxembourg. He also created about twenty smaller parks and gardens in different neighborhoods. The goal was for everyone in Paris to be within a ten-minute walk of a park. These parks were very popular with all Parisians.

The "Baron" Title

In 1857, Napoleon III wanted to thank Haussmann for his work. He offered to make him a member of the French Senate and give him an honorary title. Haussmann asked for the title of "Baron," which his maternal grandfather, a general under the first Napoleon, had held. This title was not officially recognized by law, so he was still legally "Monsieur Haussmann."

Haussmann's Downfall

At first, Napoleon III made all the decisions in France. But starting in 1860, he began to give more power to the French parliament. Members of the opposition in parliament started to criticize Haussmann. They complained about his high spending and his bossy attitude.

The cost of the rebuilding projects was growing very quickly. Property owners learned how to demand more money for their land when it was taken for new streets. This made the projects much more expensive. The government's financial watchdog also ruled that some of Haussmann's financial methods were illegal. Parliament had to approve large loans to cover the costs.

People also got angry when Haussmann took part of the Luxembourg Gardens for a new avenue. When the Emperor and Empress went to the theater, some people in the audience shouted, "Dismiss Haussmann!" Even so, the Emperor supported him for a while.

A politician named Jules Ferry even wrote a book making fun of Haussmann's accounting, calling it "The fantastic accounts of Haussmann." In 1869, the opposition won more seats in parliament. Napoleon III finally gave in to the pressure and asked Haussmann to resign. Haussmann refused, so the Emperor fired him. Six months later, during the Franco-German War, Napoleon III was captured, and his empire ended.

Haussmann later wrote that Parisians didn't like two things about him: he changed their daily lives by turning Paris upside down for 17 years, and they had to see the same prefect's face for so long.

After Napoleon III's fall, Haussmann lived abroad for about a year. He returned to public life in 1877 as a deputy for Ajaccio. He spent his later years writing his memoirs, which were published between 1890 and 1893.

Death

Georges-Eugène Haussmann died in Paris on January 11, 1891, at the age of 81. He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. His wife had passed away just eighteen days before him.

-

The Paris Opera was the centerpiece of Napoleon III's new Paris. The architect, Charles Garnier, described the style simply as "Napoleon the Third".

-

The Bois de Boulogne, built by Napoleon III and Haussmann between 1852 and 1858, was designed to give a place for relaxation and recreation to all the classes of Paris.

Haussmann's Lasting Impact

Haussmann's plan for Paris inspired city planners around the world. Similar wide boulevards, squares, and parks were created in cities like Cairo, Buenos Aires, Brussels, Rome, Vienna, Stockholm, Madrid, and Barcelona. After a big exhibition in Paris in 1867, the King of Prussia took a map of Haussmann's projects back to Berlin, which influenced that city's future plans.

His work also inspired the "City Beautiful Movement" in the United States. Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed Central Park in New York, visited the Bois de Boulogne many times. He was also influenced by the new parks like Parc des Buttes Chaumont. The American architect Daniel Burnham used many of Haussmann's ideas, including diagonal streets, in his 1909 plan for Chicago.

Haussmann was made a senator in 1857 and received the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour in 1862, a very high French award. His name is still remembered in Paris with the Boulevard Haussmann.

See also

In Spanish: Georges-Eugène Haussmann para niños

In Spanish: Georges-Eugène Haussmann para niños

- Haussmann's renovation of Paris

- Paris during the Second Empire

- Napoleon III style

- List of urban planners

- Hobrecht-Plan of Berlin, another large-scale urban planning approach conducted by James Hobrecht, created in 1853.

- Ildefons Cerdà who designed the 19th-century extension of Barcelona called the Eixample neighborhoods.

- Situationist International

- Walter Benjamin's The Arcades Project

- Robert Moses, New York planner with whom Haussmann is occasionally compared.

- David Harvey, Paris Capital of Modernity, especially the introduction and prologue.