Robert Moses facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Moses

|

|

|---|---|

Moses in 1939 with a model of his proposed Battery Bridge

|

|

| 49th Secretary of State of New York | |

| In office January 17, 1927 – January 1, 1929 |

|

| Governor | Al Smith |

| Preceded by | Florence E. S. Knapp |

| Succeeded by | Edward J. Flynn |

| 1st Chairman of the New York State Council of Parks | |

| In office 1924–1963 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Laurance Rockefeller |

| 1st Commissioner of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation | |

| In office January 18, 1934 – May 23, 1960 |

|

| Appointed by |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Newbold Morris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 18, 1888 New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

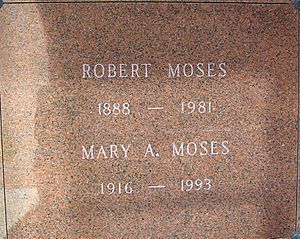

| Died | July 29, 1981 (aged 92) West Islip, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Education | |

Robert Moses (December 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American urban planner and public official. He worked in the New York metropolitan area from the early to mid-20th century. Even though he was never elected to a public office, Moses became one of the most powerful people in New York City and New York State. His huge building projects and ideas about city development influenced many engineers, architects, and planners across the United States.

Moses held many jobs during his more than 40-year career. Sometimes, he held up to 12 titles at once. These included New York City Parks Commissioner and Chairman of the Long Island State Park Commission. He worked closely with New York Governor Al Smith early on. This helped him become an expert at writing laws and working within the state government. He created many independent public organizations. Through these, he controlled millions of dollars and could fund new projects with little outside control.

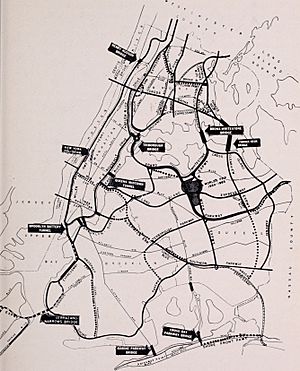

Moses's projects changed the New York area a lot. They also changed how cities in the U.S. were designed and built. As Long Island State Park Commissioner, Moses built Jones Beach State Park. This is the most visited public beach in the United States. He also designed the New York State Parkway System. As head of the Triborough Bridge Authority, Moses controlled bridges and tunnels in New York City. He also controlled the tolls collected from them. He built the Triborough Bridge, the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel, and the Throgs Neck Bridge, along with several major highways.

These roads and bridges, plus efforts to rebuild cities, changed New York. Old housing areas were torn down and replaced with large public housing projects. This inspired other cities to do similar development work.

Moses's reputation became less positive after a book called The Power Broker was published in 1974. This book, written by Robert Caro, questioned the benefits of many of Moses's projects. It also described Moses as being unfair to some groups. Because of The Power Broker, Moses is now seen as a controversial figure in New York City's history.

Contents

Early Life and His Start in Public Service

Moses was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on December 18, 1888. His parents were German Jewish. The family moved to New York City in 1897. His father was a successful store owner and real estate investor. Moses's mother was also active in community building projects.

Moses went to Yale University, Wadham College, Oxford, and Columbia University. He earned a PhD in political science in 1914. He then became interested in New York City reform politics. He wanted to stop unfair hiring practices in government. His ideas caught the attention of Belle Moskowitz, an advisor to Governor Al Smith. Smith later appointed Moses as the state's Secretary of State. He held this job from 1927 to 1929.

Moses gained power with Governor Smith, who was elected in 1922. Smith worked to combine many New York State government agencies. During this time, Moses started his first big public projects. He used Smith's political power to pass laws. This helped create the new Long Island State Park Commission and the State Council of Parks. In 1924, Governor Smith made Moses chairman of the State Council of Parks. He also became president of the Long Island State Park Commission.

Moses was known for being good at writing laws. People called him "the best bill drafter in Albany". At a time when people were used to corruption, Moses was seen as a government savior. He efficiently carried out many projects, like building Jones Beach State Park.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, the federal government had money for projects. But states and cities didn't have many projects ready. Moses was one of the few officials who had projects ready to start. This allowed New York City to get a lot of funding from programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA). One of his most important jobs was Parks Commissioner of New York City. He held this role from 1934 to 1960.

Key Roles and Offices Held

Robert Moses held many important positions. These jobs gave him great power to shape how New York City and the surrounding area developed. Here are some of the main offices he held:

- Long Island State Park Commission (President, 1924–1963)

- New York State Council of Parks (Chairman, 1924–1963)

- New York Secretary of State (1927–1928)

- Bethpage State Park Authority (President, 1933–1963)

- Emergency Public Works Commission (Chairman, 1933–1934)

- Jones Beach Parkway Authority (President, 1933–1963)

- New York City Department of Parks (Commissioner, 1934–1960)

- Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (Chairman, 1934–1968)

- New York City Planning Commission (Commissioner, 1942–1960)

- New York State Power Authority (Chairman, 1954–1962)

- New York's World Fair (President, 1960–1966)

- Office of the Governor of New York (Special Advisor on Housing, 1974–1975)

Moses's Impact on New York

During the 1920s, Moses had disagreements with Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt wanted to build a parkway through the Hudson Valley. Moses managed to get money for his Long Island parkway projects instead. These included the Northern State Parkway, the Southern State Parkway, and the Wantagh State Parkway. The Taconic State Parkway was built later. Moses also helped build Long Island's Meadowbrook State Parkway. This was the first highway in the world with separate lanes and limited access.

Moses was very important in changing New York state's government in the 1920s. A report led by Moses suggested combining many government agencies. It also proposed a new budget system and four-year terms for the governor. Most of these ideas were adopted.

Building WPA Swimming Pools

During the Great Depression, Moses and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia wanted to build new pools. They planned 23 pools around the city. These pools would be built using money from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). This was a federal program created to help with the Depression.

Eleven of these pools were designed to open in 1936. They were in parks like Astoria Park, Crotona Park, and McCarren Park. Moses and his architects created a similar design for these pools. Each place would have separate pools for diving, swimming, and wading. They would also have bleachers and bathhouses. The pools were designed to be at least 55 yards long. They had underwater lighting, heating, and filtration. They were built using cheap materials and featured Art Deco and Classical architecture styles.

Construction for some pools began in 1934. By mid-1936, ten of the eleven WPA pools were finished. They opened one per week. Together, these pools could hold 66,000 swimmers. Ten of these pools were later named New York City Landmarks in 2007 and 2008.

There were claims that Moses tried to keep African American swimmers out of his pools and beaches. One person who worked for Moses said he believed Moses wanted the pools to be a few degrees colder. This was supposedly because Moses thought African Americans did not like cold water.

Major Water Crossings

Moses had power over many projects, including public housing. But his role as chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority gave him the most power.

The Triborough Bridge

The Triborough Bridge (now the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge) opened in 1936. It connects the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens with three separate spans. The Authority that ran the bridge had a lot of independence. This was because of how its bond contracts were written. New York City and State often had little money. But the bridge's toll money brought in tens of millions of dollars each year. This allowed the Authority to raise hundreds of millions by selling bonds. Toll money grew quickly as more cars used the bridges. Instead of paying off the bonds, Moses used the money to build more toll projects.

Brooklyn–Battery Link

In the late 1930s, there was a big debate. Should a new road link between Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan be a bridge or a tunnel? Bridges are wider and cheaper to build. But they need more space for ramps than tunnels. A "Brooklyn Battery Bridge" would have damaged Battery Park and affected the financial district. Many groups opposed the bridge, including preservationists and financial businesses.

Moses, however, wanted a bridge. He thought it could carry more traffic and be a more visible landmark. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and Governor Herbert H. Lehman had little money. The federal government also refused to give more funds. Moses, with money from Triborough Bridge tolls, said that money could only be spent on a bridge. He also disagreed with the chief engineer, Ole Singstad, who wanted a tunnel.

The bridge project was stopped only because the federal government did not approve it. President Roosevelt ordered the War Department to say that bombing a bridge there would block access to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Moses was stopped. In apparent retaliation, he moved the New York Aquarium from Castle Clinton to Coney Island. He also tried to tear down Castle Clinton itself, a historic fort. The fort was saved only after it was given to the federal government.

Moses then had no choice but to build a tunnel. He started the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel (now the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel). This tunnel connects Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan. A 1941 publication from Moses's Authority claimed the government forced them to build a tunnel that cost twice as much and carried half the traffic. However, engineering studies did not support these claims.

Post-War Urban Development

Moses's power grew after World War II. Mayor LaGuardia retired, and later mayors agreed to most of Moses's plans. In 1946, Mayor William O'Dwyer named Moses "city construction coordinator." This made Moses New York City's main contact in Washington. Moses also gained more control over public housing.

When O'Dwyer resigned, Moses gained even more control over infrastructure projects. One of his first actions was to stop a citywide zoning plan. This plan would have limited his power to build within the city. Moses also became the only person allowed to negotiate for New York City projects in Washington. By 1959, he had overseen the building of 28,000 apartment units. To clear land for these high-rises, Moses sometimes destroyed almost as many homes as he built.

From the 1930s to the 1960s, Robert Moses built many bridges. These included the Triborough, Marine Parkway, Throgs Neck, Bronx-Whitestone, Henry Hudson, and Verrazzano-Narrows Bridges. His other projects included the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Staten Island Expressway. He also built the Cross-Bronx Expressway and many New York State parkways.

Moses was also behind Shea Stadium and Lincoln Center. He helped with the United Nations headquarters. Moses also influenced cities outside New York. Many smaller American cities hired him to design freeway networks in the 1940s and 1950s. For example, Portland, Oregon hired Moses in 1943.

Moses knew how to drive a car, but he did not have a driver's license. His early highways were "parkways." These were curving, landscaped roads meant to be pleasant to drive on. Later, with more cars, he built freeways, like parts of the Interstate Highway System.

Brooklyn Dodgers and Shea Stadium

Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley wanted to replace the old Ebbets Field. He proposed building a new stadium near the Long Island Rail Road in Brooklyn. O'Malley asked Moses to help him get the land. But Moses refused. He had already planned to build a parking garage on that site. Also, O'Malley's plan for the city to buy the land for him was rejected. People thought it was wrong for the government to pay so much for a private business.

Moses wanted New York's newest stadium to be in Queens. He wanted it in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, where the World's Fair would be. He hoped it would host all three of the city's major league teams. O'Malley strongly disagreed. He said the team belonged in Brooklyn. Moses would not change his mind. After the 1957 season, the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles. The New York Giants moved to San Francisco.

Moses later built the 55,000-seat multi-purpose Shea Stadium on the Queens site. Construction started in 1961 and finished in 1964. The stadium attracted a new team, the New York Mets. They played at Shea until 2008. The New York Jets football team also played there from 1964 to 1983.

The End of the Moses Era

Moses's reputation began to decline in the 1960s. He started to lose political battles. For example, he opposed the free Shakespeare in the Park program. This got a lot of negative attention. He also tried to destroy a playground in Central Park for a parking lot. This made many middle-class voters angry.

The opposition grew stronger when Pennsylvania Station was torn down. Many blamed Moses for this "development scheme." This destruction of a great landmark made many people turn against Moses's plans. He wanted to build a Lower Manhattan Expressway. This road would have gone through Greenwich Village and SoHo. Urban activist Jane Jacobs was a strong critic. Her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities helped turn public opinion against Moses. The city government rejected the expressway in 1964.

Moses's power was further weakened by the 1964 New York World's Fair. His predictions for attendance were too high. Generous contracts for fair executives also caused financial problems. Moses kept denying the fair's money troubles, even with evidence. This led to investigations by the press and government. They found problems with the accounting. Moses's reputation was hurt by his usual traits: not caring about others' opinions and trying to force his way. The fair was not approved by the Bureau of International Expositions (BIE). This group supervises such events worldwide. Moses refused to follow BIE rules, so many countries did not participate.

After the World's Fair, New York City mayor John Lindsay and Governor Nelson Rockefeller wanted to use toll money from Moses's bridges. They wanted to cover money problems in the city's agencies, like the subway system. Moses opposed this idea. Lindsay then removed Moses from his job as the city's main contact for federal highway money.

The state legislature voted to combine Moses's Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) into the new Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Moses could have fought this in court. But he was promised a role in the new authority. So, he did not challenge the merger. On March 1, 1968, the TBTA became part of the MTA. Moses gave up his chairman job. He became a consultant to the MTA, but he was frozen out. His promised role did not happen, and he was out of power.

Moses had hoped to build one last big bridge project. This would have been a bridge crossing Long Island Sound from Rye to Oyster Bay. But Governor Rockefeller did not push for it. He feared public backlash. In 1973, Rockefeller canceled plans for the bridge.

The Power Broker Book

Moses's public image got another big hit in 1974. This was when The Power Broker was published. It was a Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Robert Caro. Caro's long book showed Moses in a mostly negative way. Many people say Moses's bad reputation comes mainly from this book. For example, Caro described how Moses did not care about people when building the Cross-Bronx Expressway. He also said Moses did not favor public transit.

The book gives Moses credit for his early successes, like creating Jones Beach. But it also shows how his desire for power became more important than his earlier goals. Moses is blamed for destroying many neighborhoods. He built 13 expressways across New York City. He also built large urban renewal projects without much thought for the existing communities.

Caro also pointed out that Moses showed unfair tendencies. These included opposing Black World War II veterans from moving into a housing complex meant for them. He also supposedly tried to make swimming pool water cold to discourage African American residents in white neighborhoods.

Later Life and Death

In his last years, Moses enjoyed swimming. He was an active member of a health club.

Robert Moses died from heart disease on July 29, 1981. He was 92 years old. He passed away at Good Samaritan Hospital in West Islip, New York.

Moses was of Jewish background and raised in a non-religious way. He later converted to Christianity. He was buried in a crypt at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Moses's Lasting Legacy

Many places and roads in New York State are named after Robert Moses. These include two state parks: Robert Moses State Park – Thousand Islands and Robert Moses State Park – Long Island. There is also the Robert Moses Causeway on Long Island. The Robert Moses Niagara Power Plant in Lewiston, New York also bears his name. The Niagara Scenic Parkway was once named after him, but its name was changed in 2016. The Moses-Saunders Power Dam also carries his name. There is a school named after him in North Babylon, New York and a Robert Moses Playground in New York City. A statue of Moses stands in his long-time hometown, Babylon Village, New York.

During his time leading the state park system, the state's parks grew to nearly 2.6 million acres. By the time he left office, he had built 658 playgrounds in New York City alone. He also built 416 miles of parkways and 13 bridges. New York has more public benefit corporations than any other U.S. state. These organizations build and maintain most of the state's infrastructure.

Looking Back at Robert Moses

Criticism and The Power Broker

Robert Moses's life and work were most famously described in Robert Caro's 1974 book The Power Broker.

The book pointed out that Moses often started huge projects without enough funding. He knew the state legislature would eventually have to pay for them to avoid looking like they failed. He was also accused of using his power to help his friends. For example, he secretly changed the route of the Northern State Parkway. This was to avoid rich estates. But he told farmers who lost their land that it was for "engineering reasons." The book also claimed Moses tried to harm the reputations of officials who opposed him. He would call some of them communists during the Red Scare. The book also noted that Moses often favored parks over schools and other public needs.

Critics say Moses cared more about cars than people. They point out that he forced hundreds of thousands of people to move from their homes. He destroyed traditional neighborhoods by building many expressways through them. His projects contributed to the decline of the South Bronx and the amusement parks of Coney Island. They also caused the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants baseball teams to move to other cities. His building of expressways also slowed down the planned expansion of the New York City Subway. Critics also say he made it hard for people without cars to enjoy the recreation facilities he built.

Concerns About Fairness

Caro's The Power Broker also accused Moses of building low bridges over his parkways. This was supposedly to make it harder for buses to use them. Buses were often used by poorer families and those without cars. He was also accused of discouraging Black people from visiting Jones Beach. He allegedly made it hard for Black groups to get permits for buses. Some claims suggest he assigned Black lifeguards to less popular beaches. While low bridges were common on early parkways for looks, some believe Moses used them more to make it harder for commercial vehicles later. However, some sources question the claims about buses being unable to use the parkways.

Moses was also against Black war veterans moving into Stuyvesant Town. This was a housing complex built for World War II veterans. Moses defended his actions of moving poor communities. He said it was a necessary part of making cities better. He famously said, "I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs."

There were also claims that Moses chose locations for recreational facilities based on the racial makeup of neighborhoods. For example, when he chose sites for eleven pools that opened in 1936. One author wrote that Moses purposely put some pools in mostly white neighborhoods. This was to discourage African Americans from using them. Other pools meant for African Americans were placed in inconvenient spots. Caro wrote that people close to Moses claimed they could keep African Americans from using the Thomas Jefferson Pool by making the water too cold. However, no other source has confirmed that heaters were turned off or not included in the pool's design.

A New Look at His Work

Some experts have tried to improve Moses's reputation. They compare the huge scale of his projects to the high costs and slow speed of public works today. Moses built most of his projects during the Great Depression. Despite the economic problems, his projects were finished on time. They have been reliable public works ever since. This is different from the delays seen in modern projects, like the rebuilding of Ground Zero or the Second Avenue Subway.

In 2007, three major exhibits led to a new look at Moses's image. Experts like Hilary Ballon, an architectural historian, argue that Moses deserves a better reputation. They say his legacy is more important than ever. People often take the parks, playgrounds, and housing he built for granted. These projects now help connect communities. Without Moses's infrastructure and his determination, New York might not have recovered from its problems in the 1970s and 1980s. It might not be the economic center it is today.

Kenneth T. Jackson, a New York City historian, said in 2007, "Every generation writes its own history." He suggested that The Power Broker reflected a time when New York was struggling. Now, New York is growing again. This makes people look at its infrastructure differently. Many big projects are being considered again, which reminds people of the Moses era. Politicians are also rethinking Moses's legacy. In 2006, Governor-elect Eliot Spitzer said a book about Moses today might be called At Least He Got It Built. He added, "That's what we need today. A real commitment to get things done."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Robert Moses para niños

In Spanish: Robert Moses para niños

- Car culture

- Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation

- Modernist architecture

- Transportation in New York City

- Urban sprawl

- M. Justin Herman

- Edward J. Logue

- Edmund Bacon (architect)

- Austin Tobin – Port Authority Executive Director

- Long Island State Parkway Police

- New York State Park Police

- New York State Police

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |