Jane Jacobs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jane Jacobs

OC OOnt

|

|

|---|---|

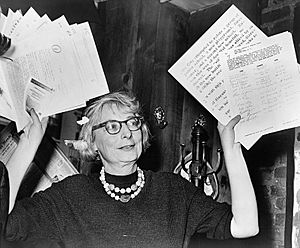

Jacobs as chair of a Greenwich Village civic group at a 1961 press conference

|

|

| Born |

Jane Butzner

4 May 1916 Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | 25 April 2006 (aged 89) Toronto, Ontario, Canada

|

| Education | Graduate of Scranton Central High School; two years of undergraduate studies at Columbia University |

| Occupation | Journalist, author, urban theorist |

| Employer | Amerika, Architectural Forum |

| Organization | Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway, Stop Spadina Save Our City Coordinating Committee |

|

Notable work

|

The Death and Life of Great American Cities |

| Spouse(s) | Robert Jacobs |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | OC, OOnt, Vincent Scully Prize, National Building Museum |

Jane Jacobs (born Jane Butzner; May 4, 1916 – April 25, 2006) was an American-Canadian writer, thinker, and activist. She greatly influenced how we understand cities and how they grow. Her most famous book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), argued that big city projects like "urban renewal" (tearing down old areas to build new ones) and "slum clearance" (removing poor neighborhoods) often hurt the people living there.

Jacobs believed that cities should be built for people, not just for cars or big buildings. She led many community efforts to stop large construction plans. For example, she fought against Robert Moses's idea to build a highway through her own Greenwich Village neighborhood in New York City. She was a key person in stopping the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have cut through areas like SoHo and Chinatown. In 1968, she was arrested during a public meeting about this project.

Later, she moved to Toronto, Canada, in 1968. There, she also helped stop another big highway project, the Spadina Expressway. As a woman writer who challenged male experts in city planning, Jane Jacobs faced criticism. People sometimes called her just a "housewife" because she didn't have a college degree in urban planning. However, her ideas eventually became very respected by important thinkers like Richard Florida.

Contents

Jane's Early Life

Jane Isabel Butzner was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Her mother, Bess Robison Butzner, was a former teacher and nurse. Her father, John Decker Butzner, was a doctor. After finishing high school, she worked for a year without pay at the Scranton Tribune newspaper. She helped the editor of the women's page.

Moving to New York City

In 1935, during the Great Depression, Jane moved to New York City with her sister Betty. Jane loved Manhattan's Greenwich Village right away. This area was different from the city's usual grid layout. The sisters soon moved there from Brooklyn.

In her early years in Manhattan, Jacobs had many different jobs. She worked as a secretary and a freelance writer. She wrote about working areas in the city. These experiences, she later said, helped her understand city life and businesses better. She sold articles to newspapers and magazines like Vogue. She also studied at Columbia University for two years. She took classes in subjects like geology, law, and economics.

Jane's Work and Ideas

After her time at Columbia University, Jane Butzner got a job at Iron Age magazine. In 1943, her article about Scranton's economic problems became well-known. It even led to a warplane factory being built there. She also spoke up for equal pay for women and for workers' rights to form unions.

Working for Amerika

She became a writer for the Office of War Information. Then, she worked as a reporter for Amerika, a U.S. State Department magazine published in Russian. While working there, she met Robert Hyde Jacobs Jr., an architect. They married in 1944 and had three children.

The Jacobses chose to stay in Greenwich Village instead of moving to the growing suburbs. They felt suburbs were "parasitic," meaning they relied too much on cities. They fixed up their house in a mixed neighborhood and made a garden.

During the McCarthy era, Jacobs was questioned about her political beliefs. Even though she was against communism, she supported unions. This made her a target for suspicion. She explained her views to the Loyalty Security Board in 1952.

Writing for Architectural Forum

Jacobs left Amerika in 1952. She then found a good job as an associate editor at Architectural Forum magazine. She started writing about city planning and "urban blight" (areas that were run down). In 1954, she wrote about a new development in Philadelphia. Her editors expected a positive story. However, Jacobs criticized the project because it didn't help the poor African Americans living there. She felt that "development" often destroyed community life. This made her question the common ideas about city planning in the 1950s.

In 1955, Jacobs met William Kirk, a minister who worked in East Harlem. He told her how "revitalization" projects were affecting East Harlem. He showed her the neighborhood.

In 1956, Jacobs gave a speech at Harvard University. She spoke to important architects and city planners about East Harlem. She told them to "respect... strips of chaos that have a weird wisdom of their own." Her speech was well-received, but it also made her a challenge to the established city planners. Architectural Forum published her speech that year.

Her Famous Book: Death and Life of Great American Cities

After her Harvard speech, Jacobs was asked to write an article for Fortune magazine. This article, "Downtown Is for People" (1958), was her first public criticism of Robert Moses. Her views were not popular with supporters of urban renewal.

The Fortune article caught the attention of the Rockefeller Foundation. In 1958, they gave Jacobs a grant to study city planning and urban life. She spent three years researching and writing. In 1961, her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities was published.

This book is one of the most important in city planning history. She created terms like "social capital" and "eyes on the street." These ideas are now used in urban design and sociology. Jacobs strongly criticized the city planning profession, calling it a "pseudoscience" (something that pretends to be scientific but isn't). This made many male city planners angry. They attacked her personally, calling her a "militant dame" and a "housewife." They said she was an amateur who shouldn't interfere. However, her ideas eventually became very influential.

In 1962, she left Architectural Forum to focus on writing and raising her children. She also became against the Vietnam War. She marched on the Pentagon in 1967. She also criticized the building of the World Trade Center in New York.

Fighting for Greenwich Village

In the 1950s and 1960s, Jacobs's home neighborhood of Greenwich Village was changing. City plans, private developers, and New York University were all expanding. Robert Moses had plans to tear down several blocks and build expensive high-rises. This plan forced many families and small businesses out of their homes.

Moses also wanted to extend Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park. He said it would help traffic flow and connect to the planned Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX).

In response, local activist Shirley Hayes started a group called the "Committee to Save Washington Square Park." Jacobs joined this group. She took a bigger role, reaching out to newspapers like The Village Voice. The committee gained support from important people like Eleanor Roosevelt. On June 25, 1958, the city closed Washington Square Park to traffic. This was a big win for the community.

But plans for the LOMEX highway continued. In the 1960s, Jacobs led the Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway. She kept fighting the highway plans in 1962, 1965, and 1968. She became a local hero for her strong opposition. On April 10, 1968, she was arrested at a public hearing. She was accused of causing a disturbance. After trials, the charge was reduced to disorderly conduct.

Life in Toronto

Soon after her arrest in 1968, Jacobs moved to Toronto, Canada. She lived at 69 Albany Avenue in The Annex until her death in 2006. She decided to leave the U.S. partly because she was against the Vietnam War. She also worried about her two sons who were old enough to be drafted into the military. She and her husband chose Toronto because it was a pleasant city with job opportunities.

In Toronto, she quickly became a leading figure. She helped stop the proposed Spadina Expressway. A common idea in her work was to ask if cities were being built for people or for cars. She was arrested twice during protests. She also greatly influenced the rebuilding of the St. Lawrence neighborhood, which became a successful housing project. She became a Canadian citizen in 1974.

In 1996, she was made an officer of the Order of Canada for her important writings and ideas on urban development. In 2002, she received an award for her lifetime contributions from the American Sociological Association. Toronto's city government held a conference in 1997 called "Jane Jacobs: Ideas That Matter." This led to the creation of the Jane Jacobs Prize. This award gives money to "unsung heroes" who help make Toronto a better city.

Jacobs was not afraid to support political candidates. She was against the 1997 plan to combine the cities of Metro Toronto. She feared that individual neighborhoods would lose power. She advised David Miller in his successful mayoral campaign in 2003. During that campaign, Jacobs helped fight against building a bridge to the Toronto City Centre Airport. The city council later stopped the bridge project.

Jacobs also fought against a plan by Royal St. George's College to change its facilities. She even suggested the school should leave the neighborhood. Although the city council first rejected the school's plans, the decision was later reversed.

She also influenced city planning in Vancouver. Jacobs has been called "the mother of Vancouverism." This refers to Vancouver's approach of building dense cities in a good way.

Jane Jacobs passed away in Toronto Western Hospital at age 89 on April 25, 2006. Her family said: "What's important is not that she died but that she lived, and that her life's work has greatly influenced the way we think. Please remember her by reading her books and implementing her ideas."

Jane's Legacy

Jane Jacobs is seen as an inspiration for the New Urbanist movement. This movement focuses on creating walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. She also influenced ideas about decentralization (spreading power out) and radical centrism (finding new solutions beyond traditional politics).

While Jacobs thought her biggest impact was on economic theory, she is most known for her work in urban planning. Her observations changed how cities are planned. She showed that many accepted planning models from the mid-20th century were wrong. For example, economist Edward Glaeser agreed with Jacobs's criticism of Robert Moses. Moses had replaced good neighborhoods with tall housing projects. Glaeser said these projects became "centers of crime, poverty, and despair."

She also introduced ideas like the "Ballet of the Sidewalk" and "Eyes on the Street." "Eyes on the Street" means that when many people are out and about, they naturally watch over the street. This makes the area safer. These ideas greatly influenced planners like Oscar Newman. His work led to the defensible space theory, which is about designing spaces to prevent crime. Jacobs's and Newman's ideas affected American housing policy. The HOPE VI Program aimed to tear down high-rise public housing projects and replace them with lower, mixed-income housing.

Throughout her life, Jacobs wanted to change how cities were developed. She argued that cities were like living things or ecosystems. She supported "mixed-use" development (where homes, shops, and offices are all in one area) and "bottom-up" planning (where plans come from the community, not just from top officials). Her strong criticisms of "slum clearing" and "high-rise housing" helped stop these practices.

Jacobs is remembered as someone who wanted cities to be developed carefully. She left "a legacy of empowerment for citizens to trust their common sense and become advocates for their place."

Even though Jacobs mainly focused on New York City, her ideas are considered universal. For example, her fight against tearing down neighborhoods for urban renewal also resonated in Melbourne, Australia. There, residents fought against large high-rise housing projects in the 1960s.

Jacobs fought against the main trends in planning at the time. While the United States is still largely suburban, Jacobs's work helped make city living popular again. Because of her ideas, many struggling urban neighborhoods are now improved through gentrification (when wealthier people move in and improve an area) instead of being completely torn down.

Jane Jacobs Days

After Jacobs passed away in April 2006, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg declared June 28, 2006, as Jane Jacobs Day. The City of Toronto also proclaimed her birthday, May 4, 2007, as Jane Jacobs Day.

Jane's Walks

To honor Jane Jacobs, two dozen free neighborhood walks were offered in Toronto in May 2007. These were called Jane's Walks. Later, a Jane's Walk event was held in New York. By 2016, Jane's Walks were happening in 212 cities in 36 countries. These walks explore local areas on foot or by bike. They often apply ideas that Jacobs talked about. Volunteers organize and lead the walks, usually around her birthday in early May.

Exhibitions

In 2016, to celebrate Jane Jacobs's 100th birthday, a Toronto gallery held an exhibit called "Jane at Home." It showed parts of her home life and where she worked. Her Toronto living room was recreated, showing where she met important thinkers and leaders. The exhibit included her typewriter, original writings, and old photos.

In 2007, the Municipal Art Society of New York had an exhibit called "Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York." It aimed to teach people about her writings and activism. It also encouraged new generations to get involved in their neighborhoods.

Jane Jacobs Medal

The Rockefeller Foundation, which had given grants to Jacobs, created the Jane Jacobs Medal in 2007. This award recognizes people who have greatly helped thinking about urban design in New York City. The medal comes with a cash prize. Past winners include Barry Benepe, who helped start the New York City Green Market program, and Peggy Shepard, who works for environmental justice.

The Canadian Urban Institute also gives an award in her honor, the Jane Jacobs Lifetime Achievement Award. This award recognizes someone who has had a big impact on their region's health, following Jane Jacobs's ideas.

Other Honors

- Jane Jacobs Way, West Village, New York City

- Jane Jacobs Park, Toronto (construction began in 2016)

- Jane Jacobs sculptural chairs, Toronto

- Jane Jacobs Toronto Legacy Plaque, her home in Toronto

- Jacobs' Ladder, rose bushes dedicated by neighbors in Toronto

- Jane Jacobs Street, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

- Jane Jacobs Street, Black Mountain, North Carolina

- A Google Doodle celebrated her 100th birthday on May 4, 2016.

- A conference room in London is named after her.

Jacobs received the Vincent Scully Prize from the National Building Museum in 2000. She is also the subject of the 2017 documentary film Citizen Jane: Battle for the City. This film shows her victories over Robert Moses and her ideas about urban design.

Criticisms of Her Ideas

The planners and developers Jacobs fought against were among the first to criticize her ideas. Robert Moses is often seen as her main opponent. Since then, Jacobs's ideas have been studied many times.

In places like the West Village, the very things she said would keep neighborhoods diverse have instead led to gentrification. This means that these areas have become some of the most expensive places to live. Her family's own home, an old candy shop, is an example of the gentrifying trend that her ideas helped create.

However, gentrification also happened because many wealthy people unexpectedly moved back into cities. Jacobs had no way of knowing this would happen. For example, she wanted to save older buildings because they were affordable for poor people. She saw them as helping keep social diversity. But these older buildings have become valuable just because they are old, which was not expected in 1961.

Economist Tyler Cowen has criticized her ideas for not dealing with problems of scale or large infrastructure. He suggests that economists disagree with some of her approaches. For example, while her ideas were sometimes called "universal," they might not work when a city grows from one million to ten million people. This suggests her ideas might only apply to cities similar to New York, where she developed many of them.

Jane Jacobs's Books

Jane Jacobs spent her life studying cities. Here are some of her important books:

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

This is her most influential book, published in 1961. It was read by city planners and the general public. The book strongly criticizes the urban renewal policies of the 1950s. She argued these policies destroyed communities and created unnatural city spaces. In the book, she praised the variety and complexity of old neighborhoods with mixed uses. She disliked the boring and sterile feel of modern planning. Jacobs suggested getting rid of strict zoning laws and letting free markets work. This would lead to dense, mixed-use neighborhoods. She often used New York City's Greenwich Village as an example of a lively urban community.

The Economy of Cities

This book argues that cities are the main drivers of economic growth. Jacobs believed that fast economic growth comes from "urban import replacement." This is when a city starts making goods locally that it used to buy from other places. For example, if Tokyo used to buy bicycles from other cities, but then started making its own. Jacobs said that import replacement builds up local skills and production. She also claimed that these new local products are then sold to other cities. This gives those cities a chance to do their own import replacement, creating a positive cycle of growth.

In this book, Jacobs also suggested that cities existed before agriculture. She argued that in early cities, trading wild animals and grains led to people specializing in different jobs. This specialization then led to the discovery of farming.

The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty

This book, published in 1980, explored the idea of Quebec becoming independent from Canada. Jacobs believed that Quebec's independence would be good for Montreal, Toronto, the rest of Canada, and the world. She thought this could happen peacefully. She used the example of Norway's secession from Sweden and how it benefited both nations. Jacobs stressed that Montreal needed to continue leading French-Canadian culture. She felt that if Montreal became just a "regional city," it would hurt Quebec's independence and Canada's future.

Cities and the Wealth of Nations

This book tries to do for economics what The Death and Life of Great American Cities did for city planning. Jacobs argued that cities, not nation-states, are the true main players in the global economy. She repeated her idea of import replacement from her earlier book. She also thought about what would happen if we focused on cities first and nations second.

Jacobs also described different types of regional economies. She talked about "backward regions" (losing population), "supply regions" (based on natural resources), and "transplant regions" (factories moved from where the product was invented). She also discussed "Entrepôt cities" (trading hubs) and "Hub cities" (regional capitals). Finally, she described growing metropolitan areas as "Import-Replacing" cities. Jacobs believed economies are always changing. She encouraged new businesses and local investment to help economies grow and diversify.

Systems of Survival

This book looks at the moral rules behind different types of work. Jacobs observed that moral judgments about work fit into two patterns. She called them "Moral Syndrome A" (for business owners, scientists, farmers) and "Moral Syndrome B" (for government, charities, religious groups). She claimed these moral patterns are fixed. She also discussed what happens when these two moral systems get mixed up.

The Nature of Economies

This book argues that the same principles apply to both ecosystems and economies. Jacobs believed that both grow through differences and combinations. They also expand by using energy in many ways and keep themselves going by "self-refueling." The book uses many examples from both economics and biology to show these ideas.

One idea is how "something from nothing" is created. In nature, sunlight provides energy. In economies, human creativity and natural resources provide this starting energy. Another idea is how new types of work are created by combining different technologies.

Dark Age Ahead

Published in 2004, this book presents Jacobs's argument that "North American" civilization shows signs of decline. She compared it to the fall of the Roman Empire. She focused on five important parts of our culture: family and community, good education, free thought in science, fair government and taxes, and responsible businesses. Jacobs's view in this book is more pessimistic than her earlier works. However, she admitted it's hard to tell if a culture is growing or declining at any given time.

Writings

- Constitutional chaff; rejected suggestions of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, with explanatory argument (1941)

- The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961)

- The Economy of Cities (1969)

- The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty (1980)

- Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1985)

- The Girl on the Hat (Children's Book Illustrated by Karen Reczuch), (1990)

- Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics (1992)

- A Schoolteacher in Old Alaska – The Story of Hannah Breece (1995)

- The Nature of Economies (2000)

- Dark Age Ahead (2004)

- Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs (2016)

See also

In Spanish: Jane Jacobs para niños

In Spanish: Jane Jacobs para niños

- David Crombie

- Fred Gardiner

- Highway revolts in the United States

- Innovation Economics

- Urban secession

- Urban vitality

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |