Fort York facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fort York |

|

|---|---|

Aerial view of Fort York from the southeast

|

|

| Location | 250 Fort York Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Built | 1793 |

| Original use | Military fortification |

| Rebuilt | 1813–15 |

| Restored | 1932–34; 1949 |

| Restored by | Municipal government of Toronto |

| Current use | Museum |

| Owner | Municipal government of Toronto |

| Official name: Fort York National Historic Site of Canada | |

| Designated | 25 May 1923 |

| Official name: Fort York Heritage Conservation District | |

| Type | Heritage Conservation District |

| Designated | 21 May 1985 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Fort York is an old military fort in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was built in the early 1800s. Soldiers from Britain and Canada lived here. Their job was to protect the entrance to Toronto Harbour.

The fort has strong walls made of earth and stone. Inside, there are eight historic buildings. These include two blockhouses, which are like small, strong forts. Fort York is part of a larger area called the Fort York National Historic Site. This site covers about 16.6 ha (41 acres) and includes the fort, open fields, old military cemeteries, and a visitor centre.

The fort started as a small army camp in 1793. It was built by John Graves Simcoe. As tensions grew between Britain and America, the fort was made stronger in 1798. American forces destroyed the first fort in April 1813 during the Battle of York.

Workers started rebuilding the fort later in 1813. It was finished in 1815. The new fort was used as a hospital during the rest of the War of 1812. It even saw a short fight against an American ship in August 1814.

Fort York continued to be used by the British Army and Canadian soldiers. This was true even after a new fort, New Fort York, opened nearby in the 1840s. In 1870, the fort officially became Canadian property. The city of Toronto took over the fort in 1909. However, the Canadian military still used it sometimes until the end of the Second World War.

In 1923, Fort York and the land around it became a National Historic Site of Canada. The fort was fixed up to look like it did in the early 1800s. It reopened as a museum in 1934. Today, it teaches visitors about the War of 1812 and military life in Canada long ago.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Fort York is a newer name for the old fort. At first, people called it the Garrison or the Fort at York. These names came from the town of York, which the fort protected.

When a new fort was built in 1841, people started calling the older one the Old Fort. This helped them tell the two forts apart. The name Fort York became popular in the 1870s. When it became a museum, it was called Old Fort York. Later, in 1970, it was renamed Historic Fort York.

Fort York's Story

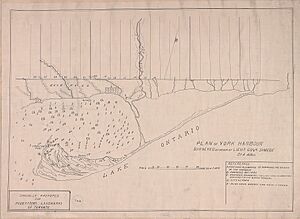

The British first looked at Toronto as a good place for a settlement and a fort in the 1780s. But they didn't build a permanent military camp until 1793. This was when relations between Britain and America were getting worse.

In the early 1790s, John Graves Simcoe was the leader of Upper Canada. He thought about building a fort in Toronto. He wanted to move British soldiers from American lands to safer spots in Canada. Simcoe also worried that American forces could easily attack British bases like the one in Kingston.

Simcoe chose Toronto, which was called York back then, for the new fort. It was far from the border and had a natural harbour that was easy to defend. He imagined the harbour as a place where British ships could control Lake Ontario. This would help stop any American attacks from the west.

Simcoe also wanted the fort to be a hub for moving soldiers around the colony. He planned roads and other forts to connect to it. This would create a backup route if the main water routes were blocked by Americans. However, many of these plans for other forts never happened because there wasn't enough money.

The First Fort (1793–1813)

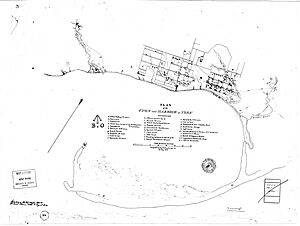

The first British army camp in Toronto was set up on July 20, 1793. About 100 soldiers from the Queen's Rangers arrived. They built 30 wooden cabins for winter. These cabins were shaped like the fort you see today.

Simcoe wanted Fort York to be part of a bigger defence system. But the main leader of Canada, Lord Dorchester, disagreed. He thought the money should be spent on improving defences at the naval base in Kingston.

Simcoe went ahead with building Fort York anyway. He had to use money from the local government, not military funds. By November 1793, the fort had two log barracks, a fence, and a sawmill. Over the next year, more buildings were added. The fort protected the harbour and the most likely land route for an American attack.

By 1796, the fort had 147 soldiers. But its defences were still limited. In 1798, Fort York officially became a British Army post. This meant it could get military funding. New buildings were put up, including barracks, a guardhouse, and a gunpowder magazine.

As tensions with America grew again, Major-General Isaac Brock ordered more defences. Three artillery batteries were built. These had furnaces to fire heated shot. This made them more dangerous to enemy ships.

When America declared war in 1812, many soldiers left Fort York to fight elsewhere. The fort was then guarded by local Canadian soldiers. Everyone knew the town needed better defences, but it was hard to get supplies during wartime.

The Battle of York

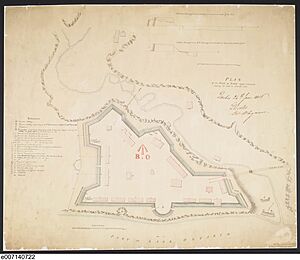

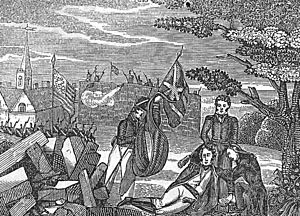

In April 1813, American forces attacked the town of York. This was part of a plan to take over Canada. Fort York was a key part of the town's defences. Soldiers, First Nations warriors, and local militia gathered at the fort.

Most of the fighting happened about 2 km (1.2 mi) west of the fort. The British and First Nations forces couldn't stop the Americans. They eventually retreated back to the fort. American soldiers then surrounded the fort, and both sides fired cannons. American ships also bombarded the fort from the lake.

The British commander, Roger Hale Sheaffe, knew they couldn't win. He ordered a secret retreat from the fort. He also told his men to blow up the fort's gunpowder magazine. This would stop the Americans from capturing it. The two sides kept firing until the British had left. The American soldiers thought the fort was still occupied because the British flag was still flying.

The gunpowder magazine held 74 tons of iron shells and 300 barrels of gunpowder. When it exploded, a huge amount of debris flew into the air. It landed on the American forces outside the fort. This explosion caused over 250 American casualties, including their general, Zebulon Pike.

American forces took over the fort after the town surrendered. They held local militia members there for two days. The British soldiers who died were buried in shallow graves inside the fort. The Americans destroyed many buildings, including most of the fort's structures, except for its barracks.

The Rebuilt Fort (1813–1932)

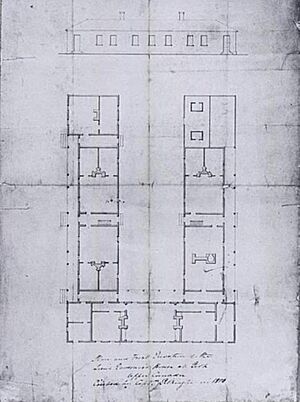

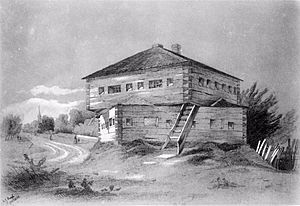

Plans to rebuild the fort began in late 1813. This was to protect four British naval ships that would be based in York's harbour. By November 1813, some new structures were ready. These included two blockhouses that could also house soldiers. The forest around the fort was cleared to remove cover for any future American attacks. The fort was finally finished around 1815.

The fort was used as a hospital from late 1813 until the end of the war. Ships brought wounded soldiers from the Niagara front. On August 6, 1814, American ships came near York's harbour again. They sent a ship with a white flag to check the town's defences. But the soldiers in the fort fired at it. The two sides exchanged fire before the American ship left. The American squadron stayed outside the harbour for three days but didn't attack again.

After the War of 1812

Work on the fort stopped when the war ended. By 1816, the rebuilt fort had eighteen buildings. It could hold 650 soldiers. Military leaders still saw York as an important place. It could protect a retreat or be a gathering point for defending the Niagara area.

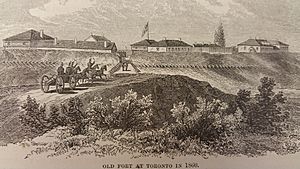

Over the next few decades, some buildings were torn down and replaced. The fort's condition often depended on how peaceful things were. It was poorly maintained during quiet times but repaired when there was a threat. By the 1830s, Fort York was old and decaying. A plan to build a new fort was approved in 1833.

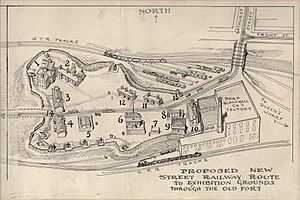

New Fort York was finished in 1841, about 2,779 ft (847 m) west of the old fort. Even with the new fort, the military still used Fort York's cannons to defend the harbour. The open space nearby was used for drills and target practice. From 1839 to 1840, the old fort also hosted a weather and magnetic observatory.

During the Rebellions of 1837–1838, most soldiers left Fort York to fight elsewhere. Only 10 British soldiers remained. The fort was reinforced after the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern. In 1854, the fort was almost empty again when soldiers went to fight in the Crimean War. Retired British soldiers, called "enrolled pensioners," mostly looked after it.

In the 1860s, relations between Britain and America worsened. There were talks about making the Toronto garrison stronger. But these plans didn't happen.

To improve relations with America, Britain started to remove its soldiers from smaller bases in North America. Fort York was officially given to the Canadian government on July 25, 1870. The last British soldiers left in 1871.

Local governments tried to buy Fort York, but the military refused. The old fort was still important. It was the only way to get to New Fort York from the city. It was also used for training, storage, and housing for military families. During the Second Boer War and the First World War, it was a place where people could sign up for the army.

In 1903, the city of Toronto agreed to buy Fort York. The city promised to protect and care for the old fort. The military could still use parts of it until new facilities were built. Soldiers continued to use the fort for storage and housing until the 1930s.

In 1905, there was a plan to build a streetcar line through Fort York. This made many people upset. Historical groups and politicians fought against it. Canadian Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier added new rules to the fort's sale. The city had to restore the fort to its original condition. If not, the land would go back to the federal government. The city officially took ownership in 1909.

On May 25, 1923, Fort York was named a National Historic Site of Canada.

Becoming a Museum (1932–Present)

In 1932, the city of Toronto started a two-year project to restore Fort York. They turned it into a historic site and museum. This was also a way to create jobs during tough economic times. The city wanted the fort to look like it did in 1816.

The Canadian military moved out of the fort. However, they briefly used parts of it again during the Second World War. A new building, Fort York Armoury, was built nearby in the 1930s for the military.

Fort York officially reopened as a museum on Victoria Day in 1934. A group of people dressed as old soldiers, playing fifes and drums, helped bring the fort to life.

In 1949, the city's Parks Division handed over management of the fort to the Toronto Civic Historical Committee. More restoration work was done that year.

In 1958, there was a plan to move Fort York closer to the water. This was to make way for the Gardiner Expressway. But people protested, and the plan was stopped. The expressway was built around the fort instead. This effort to save the fort helped start the historic preservation movement in Toronto.

The fort was added to Toronto's list of heritage properties in 1973. The whole area became a provincial "heritage conservation district" in 1985. Between 1976 and 2011, archaeologists dug up parts of the site. They wanted to find old buildings and learn about the fort's original layout.

In 1994, a group called the Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common was formed. They help support the historic site. That same year, the Fort York Guard was brought back. This group of high school and university students dressed in old uniforms. They performed musket, artillery, and music demonstrations in the summer. The Guard stopped operating in 2022.

In September 2017, Fort York hosted the archery event for the 2017 Invictus Games. This is a sports event for wounded military personnel.

Exploring the Grounds

The Fort York National Historic Site covers about 16.6 ha (41 acres) of land. When the fort was first built, it was right on the Toronto waterfront. But over many years, new land was created by filling in parts of the lake. By the 1920s, the fort was about 900 m (980 yd) inland.

The land belongs to the city of Toronto. It is one of the few National Historic Sites in Canada not owned by Parks Canada.

The historic site includes Fort York, the open fields called Garrison Common, the visitor centre, and military cemeteries. Some cemeteries are separated from the main site by railway lands. Two bridges, called Garrison Crossing, connect these areas. These bridges, finished in 2019, are the first in Canada made entirely of stainless steel. The cemetery was used for soldiers and their families from 1793 to 1863. Part of it is now Victoria Memorial Square.

In 2004, the Fort York Armoury was added to the heritage district. This building is still used by the Canadian Army today.

The grounds of the historic site are open to the public all year. But you can only enter the fort and visitor centre during museum hours.

Inside the fort and visitor centre, you can see exhibits. They teach about the War of 1812 and what military life was like in Canada in the 1800s.

Inside the Fort

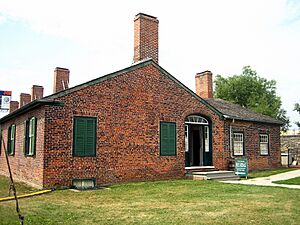

The fort itself covers about 3.24 ha (8.0 acres). It has strong, stone-lined earth walls and buildings inside. Fort York is the only real fort from the War of 1812 left in Canada. Its defensive walls and seven of its buildings date back to its rebuilding from 1813 to 1815. These buildings are the largest collection of War of 1812 structures in Canada.

The fort has eight historic buildings. Seven are from the 1813–15 rebuilding. The eighth is a rebuilt barracks. The original buildings include two blockhouses, two soldiers' barracks, the officers' "brick barracks" and mess hall, a brick gunpowder magazine, and a stone gunpowder magazine. These buildings are still in their original places and use their original materials. The stone magazine has walls 2 m (6.6 ft) thick and a bomb-proof door to protect ammunition.

The fort also has some modern facilities for the museum. These include a kitchen and washrooms built into the fort's northern walls. {{wide image|Pano of the central parade ground, old Fort York, 2015 09 10 (1).JPG - panoramio.jpg|900px|align-cap=center|A wide view of the fort's central parade ground.]]

Barracks Buildings

Three barracks buildings are from the fort's 1813–15 rebuilding. There are two for enlisted soldiers and one for officers. The officers had much nicer living spaces. The soldiers' barracks housed many soldiers and their families. By the 1860s, they were mostly used for just a few married soldiers and their families.

The brick officers' barracks has been restored to look like it did in the 1830s. It has two apartments for officers. Each apartment has four living areas and a kitchen/servant's room. The mess hall was for all officers. It has two entrances. The officers' brick barracks also has the city's "oldest kitchen" in its basement.

The fourth barracks, the blue officers' barracks and mess hall, is a rebuilt version of a junior officer's barracks. This single-story building has four apartments. Each has four separate rooms for three officers and a servant's room/kitchen. This blue barracks was rebuilt in 1986.

Blockhouses

The fort has two blockhouses. They were built to be very strong, with thick walls to stop splinters from cannon fire. They had small openings for guns and cannons. The second floor hung over the first. Unlike other blockhouses, these had storage and gunpowder rooms in the cellar. They didn't have windows on the first floor because it was too dangerous. Each floor could be sealed off if the other was attacked.

The blockhouses were placed north of the fort's cannons. They defended the back of the cannon areas while the rest of the fort was being built. Later, they became the fort's main safe place, or citadel. They also served as barracks. Blockhouse No. 1 could hold 120 soldiers, and Blockhouse No. 2 could hold 160. For a short time, they even had dry moats and drawbridges. The inside of the blockhouses changed over time to fit military needs and later, the museum.

Rampart Walls

The fort's buildings are surrounded by strong, stone-lined earth walls called ramparts. These walls were designed to absorb cannon fire. Wooden fences, called palisades, could be placed on top to stop land attacks. Even though the fort is no longer on the Toronto waterfront due to new land being created, you can still see the original shoreline outside the southern ramparts.

The ramparts have been changed and rebuilt many times. In 1916, part of the northeastern ramparts was torn down for a streetcar route. This part was rebuilt in the 1930s when the city restored the fort. However, it was rebuilt further south than its original spot.

The fort and its ramparts have nine places for cannons. More could be added during wartime. The main "circular battery" on the southern ramparts was made bigger in 1828 for more guns. Wooden fences and more cannons were added in the 1860s.

Lost Buildings

Many other buildings were once inside the fort but were later torn down. There isn't much left of the fort's original layout or structures. Most of them are buried underground. The remains of the first fort from 1793 are under the current fort. The first Government House is buried under the parade grounds.

Debris from the 1813 battle was buried in the crater made by the gunpowder magazine explosion. A maple tree now marks where the gunpowder magazine exploded. It has a plaque about the Rush-Bagot Treaty, which helped make the Great Lakes peaceful after the War of 1812.

Several buildings from the 1813–15 rebuilding were later demolished. These included a carpenter's shop, other barracks, and a cookhouse. Work on a third blockhouse was underway in 1815 but was destroyed by fire and never rebuilt.

Visitor Centre

The visitor centre is a large, rectangular building. It is north of the Gardiner Expressway and south of Garrison Common. It opened in 2014. The building is built along the original steep slope of Lake Ontario's shoreline. It also acts as a wall for the slope and Garrison Common. The roof is a green roof, and it's where visitors exit to Garrison Common.

The outside of the building facing south is made of special steel panels that change colour over time. This shows where the old shoreline used to be. Light comes into the building through narrow glass slits between the steel panels. Some parts of the south side have glass walls, letting visitors outside peek into the museum.

Inside, visitors walk up a ramp from the entrance to the top. This ramp leads to Garrison Common. The visitor centre has many exhibits. These include a 2,900 sq ft (270 m2) display of artifacts from the War of 1812. There's also a special vault for delicate artifacts. An "immersive exhibit" lets you experience the Battle of York. The centre also has offices and a meeting room.

Other Defences Around Toronto

Besides Fort York, the British built other forts and cannon batteries to defend Toronto. However, most of these buildings were torn down by the mid-1900s. Before the Battle of York in 1813, Toronto was defended by Fort York and three other blockhouses. Two were at Gibraltar Point, and one was in the town. There were also two cannon batteries west of the fort. Most of these were destroyed by American forces after the Battle of York.

After the battle, Fort York was rebuilt. Three new blockhouses were put up around the town. One was at Gibraltar Point, another near the Western Battery, and a third defended the western land approach. The blockhouse on Queen Street was taken down in 1818. The other two were in ruins by the mid-1820s. After the rebellions in 1837–38, three more blockhouses were built. These were taken down by the mid-1800s.

New Fort York was finished in 1841. It was used by the military until the end of the Second World War. Most of New Fort York was torn down in 1951, but its officers' quarters still stand.

See also

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |