Walter O'Malley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Walter O'Malley

|

|

|---|---|

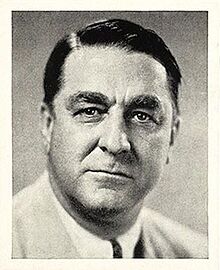

O'Malley on the cover of Time magazine, April 28, 1958.

|

|

| Born | October 9, 1903 The Bronx, New York, U.S.

|

| Died | August 9, 1979 (aged 75) Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Holy Cross Cemetery |

| Education | University of Pennsylvania (B.A.) Columbia University Fordham University (LL.B.) |

| Occupation | Baseball executive |

| Spouse(s) |

Katherine Elizabeth Hanson

(m. 1931; died 1979) |

| Children | 2, including Peter O'Malley |

| Parent(s) | Edwin O'Malley (father) Alma Feltner (mother) |

| Relatives | Peter Seidler (grandson) |

|

Baseball career |

|

| Career highlights and awards | |

As president

|

|

| Induction | 2008 |

| Vote | 75% |

| Election Method | Veterans Committee |

Walter Francis O'Malley (born October 9, 1903 – died August 9, 1979) was an important American sports leader. He owned the Brooklyn and later Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team from 1950 to 1979. In 1958, he made a huge change by moving the Dodgers from Brooklyn, New York, to Los Angeles, California. This brought Major League Baseball to the West Coast for the first time. He also helped the New York Giants move to San Francisco. In 2008, Walter O'Malley was honored in the National Baseball Hall of Fame for his big impact on baseball.

Walter's father, Edwin Joseph O'Malley, had many connections in politics. Walter was a very smart student and became a lawyer. He used his family's connections, his friends, and his skills to become successful. He first worked in public construction, then became a leader with the Dodgers. He started as the team's lawyer, then became its owner and president. He made the big business decision to move the team. Even though he moved the team, O'Malley was known for believing in loyalty between himself and his employees.

In 1970, O'Malley gave the team presidency to his son, Peter O'Malley. Walter became the first chairman of the Dodgers, a special title created just for him. He stayed in this role until he passed away in 1979. He left the team to his children, Peter O'Malley and Therese O'Malley Seidler.

Contents

Walter O'Malley's Early Life

Walter O'Malley was the only child of Edwin Joseph O'Malley (1881–1953). His father worked as a cotton salesman in The Bronx in 1903. Edwin O'Malley later became a city official in New York City. Walter's mother was Alma Feltner (1882–1940). Walter was a third-generation Irish-American. His grandfather was born in Ireland.

O'Malley grew up in the Bronx as a fan of the New York Giants baseball team. He often went to Giants games with his uncle. Walter was also a Boy Scout and reached the rank of Star Scout.

He attended Jamaica High School in Queens from 1918 to 1920. Then he went to the Culver Academy in Indiana. At Culver, he managed the baseball and tennis teams. He also worked on the student newspaper and was part of the debate team. His own baseball playing career ended when a ball hit him on the nose.

After Culver, he went to the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) and graduated in 1926. He was the second-highest ranked student in his class. He was also president of his junior and senior classes. O'Malley first started law school at Columbia University in New York City. However, his family lost money during the Wall Street Crash of 1929. He then switched to night school at Fordham University to save money.

O'Malley's Career Before Baseball

After finishing his law degree in 1930 at Fordham Law, Walter O'Malley worked as an assistant engineer for the New York City Subway. He then worked for Thomas F. Riley, and they formed a company together. With help from his father's political connections, Walter's company got contracts to do geological surveys. These surveys were for the New York Telephone Company and the New York City Board of Education. Later, Walter started his own engineering company.

Walter eventually focused on law, working on wills and deeds. By 1933, he was a senior partner in a law firm in Midtown Manhattan. During the Great Depression, O'Malley represented companies that were going bankrupt. He became wealthy by building a successful law practice. He invested wisely in various companies, including a railroad, a gas company, and a building materials firm. His success brought him influence and attention. Important figures in Brooklyn, like judge Henry Ughetta, noticed O'Malley's rising career.

Walter O'Malley and the Dodgers

George V. McLaughlin, president of the Brooklyn Trust Company, knew O'Malley's father. McLaughlin hired O'Malley to handle mortgage problems for businesses that were failing. The trust company owned part of the Brooklyn Dodgers team. This was because Charles Ebbets, who owned half of the team, had died in 1925. In 1933, Walter was chosen to protect the company's money interests in the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In 1942, when Larry MacPhail left his job as general manager to serve in the U.S. Army, O'Malley became the lawyer for the Dodgers. He also bought a small part of the team on November 1, 1944. He bought 25% of the team, as did Branch Rickey and John L. Smith. The heirs of Stephen McKeever kept the last quarter. In 1943, O'Malley became the chief legal counsel for the team.

Branch Rickey, who had built the St. Louis Cardinals into champions, took over as general manager. O'Malley started to buy more shares in the Dodgers. Rickey and O'Malley had very different backgrounds and ideas. O'Malley began to criticize Rickey, who was the highest-paid person in baseball. O'Malley felt Rickey was spending too much money. He also pressured Rickey to fire manager Leo Durocher.

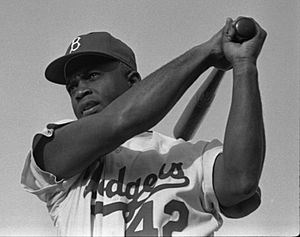

O'Malley thought Rickey's building of the Dodgertown spring training facility was too expensive. He also questioned Rickey's investment in the Brooklyn Dodgers football team. As the team's lawyer, O'Malley played a role in breaking baseball's color barrier. He helped Rickey in the secret search for Black baseball players. He also helped with the legal risks to the team. However, some stories say O'Malley played a smaller role in Jackie Robinson signing with the Dodgers.

Taking Control of the Dodgers

When co-owner John L. Smith died in July 1950, O'Malley convinced Smith's widow to give control of the shares to the Brooklyn Trust Company. O'Malley controlled this company as its chief lawyer. Rickey's contract as general manager was ending on October 28, 1950. O'Malley offered Rickey $346,000 for his shares. Rickey wanted $1 million.

O'Malley eventually bought out Rickey in a complex deal. Rickey had received an offer of $1 million from William Zeckendorf. This outside offer triggered a rule in their agreement. If an outside offer was made, a current owner could match it to keep control. The outside party would get $50,000.

O'Malley replaced Rickey with Buzzie Bavasi. O'Malley became the president and main owner of the Dodgers on October 26, 1950. Rickey had been a pioneer in baseball, creating the farm system and breaking the racial barrier with Jackie Robinson. After O'Malley took over, the Dodgers continued to be successful. They won the National League pennants in 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1956. In 1955, they won their first World Series championship.

Jackie Robinson had been a player Rickey brought in, and O'Malley did not respect Robinson as much as Rickey did. O'Malley called him "Rickey's prima donna" (meaning someone who is difficult to work with). Robinson did not like O'Malley's choice for manager, Walter Alston. Robinson often argued with umpires, but Alston rarely did. Robinson announced his retirement after the 1956 season.

The signing of Robinson made the team famous around the world. In 1954, Dodgers scout Al Campanis signed Sandy Koufax. This was partly because he was a Brooklyn boy and Jewish, which was important to the large Jewish community in Brooklyn. In 1955, Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella had a problem with a medical bill. The Dodgers felt the doctor was charging too much.

Even though the Dodgers won many pennants, they kept losing to the New York Yankees in the World Series. This frustrated O'Malley and the fans. In 1955, the team finally won the World Series for the first time. However, attendance at games started to drop. The stadium, Ebbets Field, was old and didn't have enough parking. Many fans had moved out of Brooklyn to Long Island.

O'Malley tried to get money and political support to build a new ballpark in Brooklyn. He needed the help of Robert Moses, a powerful figure in New York. O'Malley wanted a domed stadium near a train station in Brooklyn. Moses, however, wanted the Dodgers to move to Queens. Even though O'Malley had political support, Moses blocked the sale of the land needed for the new Brooklyn stadium.

In 1956, O'Malley bought the Los Angeles Angels minor league team and their stadium, Wrigley Field, in Los Angeles. This was to secure the Los Angeles market for the Dodgers. The mayor of Los Angeles, Norris Poulson, even traveled to the Dodgers' training camp to try and get the team to move. O'Malley saw how successful the Milwaukee Braves became after moving from Boston in 1953. They had a big stadium with lots of parking and no city taxes. Ebbets Field, in contrast, was small and had very little parking.

Moving the Dodgers to Los Angeles

Ultimately, O'Malley decided to move the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1957. Many Dodgers fans in New York felt betrayed. O'Malley is seen by baseball experts as one of the most important owners in baseball's expansion era. He was also key in getting the rival New York Giants to move west to become the San Francisco Giants. He needed another team to move with him to make West Coast road trips more affordable for visiting teams.

On April 15, 1958, the Dodgers and Giants started West Coast baseball at Seals Stadium. When O'Malley moved the Dodgers, it was such a big story that he appeared on the cover of Time magazine. The move broke the hearts of New York's National League fans. However, it was very successful for both teams and for Major League Baseball. The Dodgers immediately set a record for single-game attendance with 78,672 fans. In their first year in Los Angeles, the Dodgers made $500,000 more profit than any other team.

After the New York teams moved, Major League Baseball added many new teams across the country. The National League eventually returned to New York with the New York Mets four years after the Dodgers and Giants left.

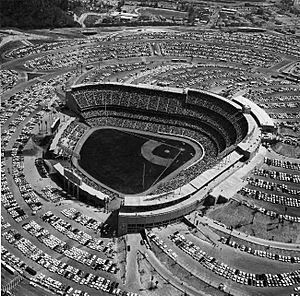

When he decided to move to Los Angeles in October 1957, O'Malley didn't have a stadium for the Dodgers to play in for 1958. He made a deal to rent the Los Angeles Coliseum for two years. The Dodgers played there while their new 56,000-seat Dodger Stadium was built for $23 million. The Dodgers soon started drawing over two million fans a year. They also continued to win, taking the World Series in 1959, 1963, and 1965.

O'Malley's Management Style

His son, Peter O'Malley, said his father believed in stability and not changing staff often. This made the organization strong. The management team worked well together, just like the team on the field. This is shown by how long Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda were Dodgers managers. Vin Scully was also the voice of the Dodgers for 67 seasons. The infield of Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, and Ron Cey played together for a very long time.

O'Malley rewarded loyal employees. He allowed Buzzie Bavasi to become president of the San Diego Padres expansion team. Alston said O'Malley convinced him that signing one-year contracts could be a lifetime job. However, O'Malley was also known for being very careful with money.

O'Malley did not like it when employees made demands. When manager Charlie Dressen asked for a three-year contract, he was let go. O'Malley made it clear that Walter Alston would only get one-year contracts. There were rumors that Alston even signed blank contracts. O'Malley also did not support those who remained friends with Branch Rickey. This was a big reason why Red Barber quit as the Dodgers announcer.

O'Malley also had arguments about player salaries. In 1960, he refused to pay Carl Furillo after he was released due to injury. This led Furillo to sue the team. In 1966, Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale held out together for new contracts. They wanted more money after the Dodgers won the World Series in 1965. They hired an agent, which was very unusual at the time. They held out until just before the season started.

Retirement from Presidency

On March 17, 1970, Walter O'Malley gave the team presidency to his son Peter. Walter remained as chairman until his death in 1979. Peter O'Malley held the position until 1998 when the team was sold. The team continued to be successful under Peter. They won the World Series in 1981 and 1988. They also continued to attract many fans.

In 1975, the Dodgers team was involved in the Andy Messersmith controversy. This led to the Seitz decision, which changed baseball's reserve clause. The reserve clause meant teams could keep players even if their contract expired. This decision opened the door for modern free agency. Messersmith and the Dodgers could not agree on a new contract. He pitched the whole season without a contract. The Seitz decision limited how long teams could keep players without a new deal. Messersmith became one of the first free agents. O'Malley worried that this would lead to high salary costs in baseball.

Walter O'Malley's Personal Life

On September 5, 1931, Walter O'Malley married Katherine Elizabeth "Kay" Hanson (1907–79). They had been dating since high school. Kay had been diagnosed with cancer in 1927 and had to have her voice box removed. She could only speak in a whisper for the rest of her life. Walter's parents did not approve of the marriage and did not attend the wedding. The couple had two children: Therese O'Malley Seidler (born 1933) and Peter O'Malley (born 1937).

In 1944, he renovated his parents' summer house in Amityville, New York. He moved his family there from Brooklyn. The house was next door to where Kay had grown up.

O'Malley enjoyed gardening for fun. He was a family man who went to church regularly. He attended his son Peter's football games and chaperoned his daughter's dances. On summer weekends, he took his family sailing on his boat, which he named Dodger. Later in life, the O'Malleys lived in Hancock Park, Los Angeles and Lake Arrowhead, California.

Death and Lasting Impact

Walter O'Malley was diagnosed with cancer. He died of congestive heart failure on August 9, 1979, in Rochester, Minnesota. O'Malley had never returned to Brooklyn before his death. He was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. His wife Kay had passed away a few weeks earlier.

Even though O'Malley had retired before his death, many people in Brooklyn still disliked him for moving the Dodgers. Some Brooklyn Dodgers fans even joked that he was one of the worst people of the 20th century. This was not just for moving the team, but for taking away a big part of Brooklyn's identity.

Despite this long-standing dislike, O'Malley was honored in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2008. He was chosen by the Veterans Committee. Tommy Lasorda said that O'Malley was a pioneer who made a huge change by bringing Major League Baseball to the West Coast. When asked how he wanted to be remembered, O'Malley said, "for planting a tree." This "tree" helped baseball grow internationally. His contributions to baseball were recognized even before he entered the Hall of Fame. He was ranked among the most influential sports figures of the 20th century by ABC Sports and The Sporting News.

On July 7, 2009, Walter O'Malley was inducted into the Irish American Baseball Hall of Fame. John Mooney, the curator, said that O'Malley privately built one of baseball's most beautiful ballparks, Dodger Stadium. He also set attendance records every year.

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |