Modern architecture facts for kids

|

Top: Villa Savoye, France, by Le Corbusier (1927); Empire State Building, New York, by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (1931)

Center: Palácio do Planalto, Brasília, by Oscar Niemeyer (1960); Fagus Factory, Germany, by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer (1911–1913) Bottom: Fallingwater, Pennsylvania, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1935); Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia, by Jørn Utzon (1973) |

|

| Years active | 1920s–1980s |

|---|---|

| Country | International |

Modern architecture, also known as modernist architecture, was a big movement and style in the 20th century. It came after Art Deco and before postmodern styles. Modern architecture used new building ideas and materials like glass, steel, and concrete.

It followed the idea that "form should follow function", meaning a building's look should come from its purpose. It also loved minimalism (keeping things simple) and didn't use much decoration. This style started in the early 1900s and was very popular after World War II until the 1980s.

Contents

- How Modern Architecture Began

- Early Modernism in Europe (1900–1914)

- Early American Modernism (1890s–1914)

- Modernism Grows in Europe and Russia (1918–1931)

- Art Deco: Modern with Style

- American Modernism (1919–1939)

- Architecture of the 1937 Paris Exposition

- New York World's Fair (1939)

- World War II and Postwar Building (1939–1945)

- Le Corbusier's Postwar Work (1947–1952)

- Late Modernist Architecture

- Postwar Modernism in the United States (1945–1985)

- Frank Lloyd Wright and the Guggenheim Museum

- Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Less is More

- Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames

- Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and Wallace K. Harrison

- Philip Johnson: From Modern to Postmodern

- Eero Saarinen: Sculptural Designs

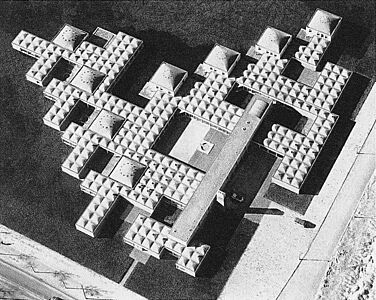

- Louis Kahn: Monumental and Solid

- I. M. Pei: Modern Master of Museums

- Fazlur Rahman Khan: Engineering Tall Buildings

- Minoru Yamasaki: Unique Skyscrapers

- Postwar Modernism in Europe (1945–1975)

- Tropical Modernism: Adapting to Warm Climates

- Latin America: A Modern Showcase

- Asia and Australia: Modernism Across Continents

- Africa: Modern Designs in Diverse Climates

- Preserving Modern Architecture

- See also

How Modern Architecture Began

Modern architecture started in the late 1800s. New technologies, engineering, and building materials made it possible. People also wanted to create something completely new and useful, breaking away from old styles.

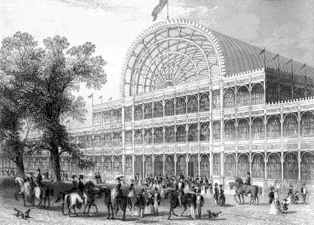

New materials like cast iron, drywall, large plate glass windows, and reinforced concrete made buildings stronger, lighter, and taller. In 1848, a way to make very big glass windows was invented. The Crystal Palace in 1851 was an early example of using iron and glass. Later, in 1864, the first glass and metal walls were used.

These changes led to the first steel-framed skyscraper, the ten-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago, built in 1884. Another big step was the safety elevator, invented by Elisha Otis in 1854. This made tall office and apartment buildings practical. Electric light also helped, making fires less common than with gas lighting.

-

The Crystal Palace (1851) used big glass windows and an iron frame.

-

The Home Insurance Building in Chicago (1884), one of the first skyscrapers.

-

The Eiffel Tower being built (1887–89).

New materials and methods inspired architects to move away from older styles like eclecticism and Beaux-Arts architecture. Architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc encouraged this. In his 1872 book, he said to "use the means and knowledge given to us by our times" to create a new architecture. This book influenced many architects.

Early Modernism in Europe (1900–1914)

-

The Glasgow School of Art by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1896–99).

-

Austrian Postal Savings Bank in Vienna by Otto Wagner (1904–1906).

-

The AEG Turbine factory in Berlin by Peter Behrens (1909).

-

The Steiner House in Vienna by Adolf Loos (1910).

-

Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann, Brussels, (1906–1911).

-

The Ginsburg skyscraper in Kyiv (1910–1912), once Europe's tallest.

-

The Fagus Factory in Alfeld by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer (1911–13).

-

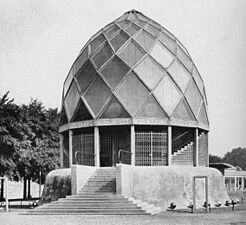

The Glass Pavilion in Cologne by Bruno Taut (1914).

Around 1900, some architects started to challenge traditional styles. The Glasgow School of Art (1896–99) had huge vertical windows. The Art Nouveau style, started by Victor Horta and Hector Guimard, brought in new decorations inspired by plants. In Barcelona, Antoni Gaudí made buildings like sculptures, with no straight lines.

Architects also tried new materials. In Paris, Auguste Perret and Henri Sauvage began using reinforced concrete for apartment buildings in 1903. This material could be shaped easily and create large open spaces. Perret even left concrete bare in a parking garage in 1905, filling spaces with glass. Sauvage added stepped floors to a building, creating terraces.

Otto Wagner in Vienna also pushed for a simpler style. He designed the Austrian Postal Savings Bank (1904–1906) with a plain exterior of marble and aluminum. The inside was very simple, with steel, glass, and concrete as the only "decoration."

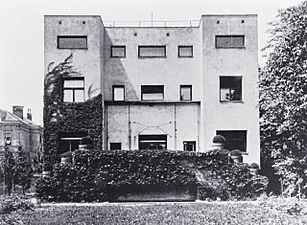

Adolf Loos in Vienna also removed all decoration. His Steiner House (1910) was a simple, plain building. The Vienna Secession movement spread. Josef Hoffmann, a student of Wagner, built the Stoclet Palace in Brussels (1906–1911). It was made of geometric blocks, with a pool reflecting its shapes.

In Germany, the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation) was formed in 1907. It aimed to create well-designed, high-quality products and a new type of architecture. Peter Behrens designed the AEG turbine factory (1909), an early modernist industrial building. Adolf Meyer and Walter Gropius built the Fagus Factory (1911–13), a building with no decoration where all its parts were visible.

Early American Modernism (1890s–1914)

-

The Arthur Heurtley House in Oak Park, Illinois (1902).

-

Larkin Administration Building by Frank Lloyd Wright, Buffalo, New York (1904–1906).

-

Inside Unity Temple by Frank Lloyd Wright, Oak Park, Illinois (1905–1908).

-

The Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright, Chicago (1909).

Frank Lloyd Wright was a very original American architect. He didn't like to be put into any specific style. He worked for Louis Sullivan, who famously said "form follows function". Wright wanted to break all the old rules.

He was known for his "Prairie Houses", like the Winslow House (1893–94) and the Robie House (1909). These were large, geometric homes with no decoration and strong horizontal lines, looking like they grew from the flat American landscape. His Larkin Building (1904–1906) and Unity Temple (1905) also had very new forms, unlike anything seen before.

Early Skyscrapers: Reaching for the Sky

-

Home Insurance Building in Chicago by William Le Baron Jenney (1883).

-

Prudential (Guaranty) Building by Louis Sullivan in Buffalo, New York (1896).

-

The Flatiron Building in New York City (1903).

-

The Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building in Chicago by Louis Sullivan (1904–1906).

-

The Woolworth Building and New York skyline in 1913.

-

The neo-Gothic top of the Woolworth Building by Cass Gilbert (1912).

The first skyscrapers appeared in the United States in the late 1800s. Cities were growing fast, and land was expensive. New technologies like steel frames and safer elevators made these tall buildings possible.

The first steel-framed skyscraper, the Home Insurance Building in Chicago, was ten stories high. It was designed by William Le Baron Jenney in 1883. Louis Sullivan built the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building (1904–1906) in Chicago. While these buildings were new in their height and structure, their decorations often copied older styles.

The Woolworth Building (1912) was the tallest building in the world for a time. Its structure was modern, but its outside looked neo-Gothic, with arches and spires. It was even called the "Cathedral of Commerce."

Modernism Grows in Europe and Russia (1918–1931)

After World War I, there was a debate between architects who liked traditional styles and modernists. Modernists like Le Corbusier in France and Walter Gropius in Germany wanted simple, pure forms with no decoration. Louis Sullivan's idea of "Form follows function" became very popular. Some architects, like Auguste Perret, mixed modern forms with stylish decoration.

International Style: Simple and Clean (1920s–1970s)

-

The Villa La Roche-Jeanneret by Le Corbusier, Paris (1923–25).

-

Villa Paul Poiret by Robert Mallet-Stevens (1921–1925).

-

Hôtel Martel rue Mallet-Stevens, by Robert Mallet-Stevens (1926–1927).

The most important person in French modernism was Le Corbusier. He believed in functional, pure architecture without decoration. He also wanted planned cities. In 1923, he wrote "Toward an Architecture," with his famous saying, "a house is a machine for living in."

In the 1920s, he built many houses around Paris. They all used reinforced concrete and had open floor plans with glass walls. They were usually white and had no outside decoration. The Villa Savoye (1928–1931) became a symbol of modern architecture. It was an elegant white box with ribbon windows, raised on white pillars.

Bauhaus and German Design (1919–1933)

-

The Bauhaus Dessau building in Dessau, designed by Walter Gropius (1926).

-

ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau bei Berlin by Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer (1928–30).

-

Haus am Horn, Weimar by Georg Muche (1923).

-

The Barcelona Pavilion (modern reconstruction) by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1929).

-

The Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart, built by the German Werkbund (1927).

In Germany, the Bauhaus school was founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius. It combined art and technology. Gropius designed the new school buildings in a purely functional, modern style. Famous artists like Vasily Kandinsky taught there.

Gropius believed in standardizing architecture and building many apartment blocks for factory workers. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe also led the modernist movement in Berlin. He designed the German pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona exposition. It was a pure modernist building with glass and concrete walls and clean, horizontal lines.

When the Nazis came to power, they closed the Bauhaus in 1933. Gropius and Mies van der Rohe moved to the United States and became very important teachers and designers there.

Expressionist Architecture: Artful Shapes (1918–1931)

-

Foyer of the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin by Hans Poelzig (1919).

-

The Einstein Tower near Berlin by Erich Mendelsohn (1920–24).

-

The Mossehaus in Berlin by Erich Mendelsohn (1921–23).

-

Horseshoe Estate public housing by Bruno Taut (1925).

-

Second Goetheanum in Dornach by Rudolf Steiner (1924–1928).

-

Het Schip apartment building in Amsterdam by Michel de Klerk (1917–1920).

-

De Bijenkorf store in The Hague by Piet Kramer (1924–1926).

Expressionism in Germany (1910–1925) was different from the strict Bauhaus style. Architects like Bruno Taut and Erich Mendelsohn wanted poetic, expressive, and hopeful buildings. Many of their ideas stayed on paper because of economic problems.

Erich Mendelsohn built the Einsteinium (1920–24) near Berlin, an observatory with unique, sculptural forms. His Mossehaus in Berlin was an early example of the streamline moderne style. Fritz Höger designed the Chilehaus in Hamburg (1921–24), which looked like a giant steamship. Hans Poelzig built the huge Großes Schauspielhaus theater in Berlin (1919), with dramatic shapes. Bruno Taut built large apartment complexes, sometimes with unusual shapes like a horseshoe, and used bright colors.

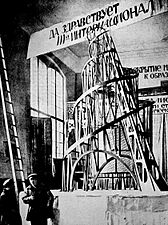

Constructivist Architecture: Soviet Style (1919–1931)

-

Model of the Tower for the Third International, by Vladimir Tatlin (1919).

-

The Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow by Alexey Shchusev (1924).

-

The USSR Pavilion at the 1925 Paris Exposition by Konstantin Melnikov (1925).

-

Rusakov Workers' Club, Moscow, by Konstantin Melnikov (1928).

-

Zonnestraal Sanatorium in Hilversum by Jan Duiker and Bernard Bijvoet (1926–1928).

-

Van Nelle Factory in Rotterdam by Leendert van der Vlugt and Mart Stam (1927–1931).

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Russian artists and architects looked for a new Soviet style. Vladimir Tatlin proposed a huge, spiraling tower for Moscow in 1920. The Constructivist movement began in 1921, aiming to find the "communist expression of material structures."

Architects built workers' clubs, shared apartment houses, and communal kitchens. Konstantin Melnikov designed the Rusakov Workers' Club (1928) and his own unique home. He also built the Soviet Pavilion for the 1925 Paris Exposition, a geometric glass and steel structure.

The style became less popular in the 1930s as leaders favored more grand, traditional styles.

New Objectivity: Practical Designs (1920–1933)

-

Apartment house in Stuttgart by Mies van der Rohe (1927).

-

Flats in Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg by Bruno Taut (1920s).

-

Flats in Siemensstadt, Berlin, by Hans Scharoun (early 1930s).

-

Former Schocken Department Store, Chemnitz, by Erich Mendelsohn (1927-1930).

The New Objectivity (or Neue Sachlichkeit) was a modern architecture style in Europe, mainly Germany, in the 1920s and 30s. It was also called Neues Bauen (New Building). This style focused on practical and clear designs, seen in projects like the Neues Frankfurt (New Frankfurt).

Modernism Becomes International: CIAM (1928)

By the late 1920s, modernism was a big movement across Europe. Architects started traveling, meeting, and sharing ideas. In 1927, the German Werkbund held an exhibition where many leading modern architects designed houses.

In 1928, the first Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) was held in Switzerland. Architects like Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe attended. They discussed how modern cities should be organized. Their ideas were written down in "The Athens Charter" in 1957, which influenced city planners for many years.

Art Deco: Modern with Style

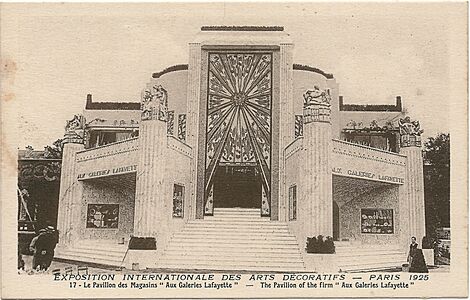

The Art Deco style was modern but different from the strict modernism of Le Corbusier. It used new materials like concrete, glass, and steel, and rejected old historical styles. However, unlike pure modernism, Art Deco loved decoration and color. It used symbols of modernity like lightning bolts and zig-zags.

Art Deco started in France before World War I and became very popular worldwide in the 1920s and 1930s. It was often used for department stores and movie theaters. The 1925 Paris Exposition showed many Art Deco designs.

American Art Deco: The Skyscraper Style (1919–1939)

-

The American Radiator Building in New York City by Raymond Hood (1924).

-

Guardian Building in Detroit, by Wirt C. Rowland (1927–29).

-

Chrysler Building in New York City, by William Van Alen (1928–30).

-

Crown of the General Electric Building (1933).

-

30 Rockefeller Center, now the Comcast Building, by Raymond Hood (1933).

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, a lively American Art Deco style appeared in skyscrapers like the Chrysler Building, Empire State Building, and Rockefeller Center in New York City. These buildings used modern materials like stainless steel and concrete, combined with Art Deco shapes.

Their interiors were brightly decorated with geometric patterns inspired by ancient pyramids and African designs. This style was popular for office buildings and large movie theaters.

Streamline Style and Public Works (1933–1939)

-

Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles (1936).

-

The San Francisco Maritime Museum, once a public bathhouse (1936).

-

Intake towers of Hoover Dam (1931–36).

-

Long Beach Main Post Office (1933–34).

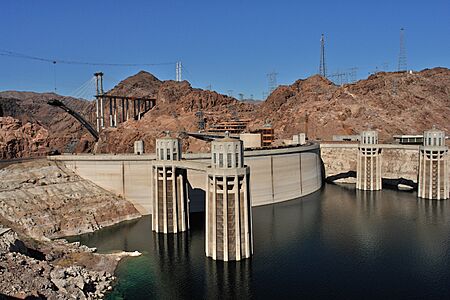

The Great Depression (starting in 1929) led to a new style called "Streamline Moderne". This style often looked like ocean liners, with rounded corners, strong horizontal lines, and nautical features. It was used for airports, train stations, and even appliances.

In the U.S., government buildings adopted a style called PWA Moderne. This was a simpler version of classical architecture, used for post offices and even the huge Pentagon (1941–43).

American Modernism (1919–1939)

-

Ennis House in Los Angeles, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1924).

-

Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright (1928–34).

-

Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach by Rudolph Schindler (1926).

-

Lovell Health House in Los Feliz, Los Angeles, California, by Richard Neutra (1927–29).

Frank Lloyd Wright always said his architecture was unique. From 1916 to 1922, he built houses with textured cement blocks, called his "Mayan style." His most famous house was Fallingwater (1934–37) in Pennsylvania. It's a remarkable building with concrete slabs hanging over a waterfall, blending perfectly with nature.

Austrian architects Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra also made important contributions to American modernism, especially with their designs for homes in California.

Architecture of the 1937 Paris Exposition

-

Reconstruction of the Pavilion of the Second Spanish Republic by Josep Lluis Sert (1937) showed Picasso's Guernica.

-

The Zeppelinfield stadium in Nuremberg, Germany (1934), by Albert Speer.

-

The Casa del Fascio (House of Fascism) in Como, Italy, by Giuseppe Terragni (1932–1936).

The 1937 Paris International Exposition showed the end of Art Deco and pre-war styles. Most buildings were in a classical Art Deco style. The pavilions of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were huge and grand, showing off their power.

Le Corbusier's student, Josep Lluis Sert, designed the Spanish pavilion, a simple glass and steel box. Inside, it showed Pablo Picasso's famous painting Guernica.

Some leaders in the 1930s used classical architecture to show power. For example, Albert Speer designed huge buildings in Germany. In Italy, Giuseppe Terragni designed the Casa del Fascio, a perfectly modern building with clean lines.

New York World's Fair (1939)

-

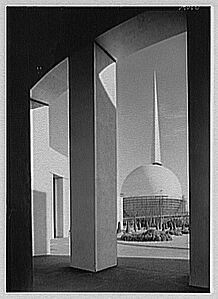

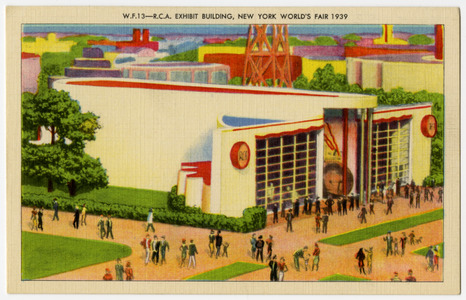

Pavilion of the Ford Motor Company, in the Streamline Moderne style.

The 1939 New York World's Fair was a turning point. Its theme was the World of Tomorrow. While it had many Art Deco buildings, it also showed the new International Style that would become popular after the war. Pavilions from Finland, Sweden, and Brazil showed this new style.

World War II and Postwar Building (1939–1945)

-

The center of Le Havre destroyed by bombing in 1944.

-

The center of Le Havre rebuilt by Auguste Perret (1946–1964).

-

Quonset hut on its way to Japan (1945).

World War II (1939–1945) brought new building ideas. Shortages of materials led to using new ones like aluminum. There was also a lot more use of prefabricated building (parts made in a factory and assembled on site). The Quonset hut, a semi-circular metal building, was used a lot.

The war destroyed many cities, creating a huge need for new housing. In Europe and the U.S., large government housing projects were built. One big project was rebuilding Le Havre, France, which was destroyed by bombing. Architect Auguste Perret designed a whole new city center using reinforced concrete. His rebuilt city is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Le Corbusier's Postwar Work (1947–1952)

After the war, Le Corbusier was asked to build a new apartment block in Marseille, France. He called it Unité d'Habitation, also known as the Cité Radieuse. It was built on pillars, with 337 apartments fitting together like a puzzle. Each apartment had two levels and a terrace. The building also had shops and a school inside.

This building became a model for similar projects. Along with his unique design for the Chapel of Notre-Dame du-Haut at Ronchamp, this work made Le Corbusier a top modern architect.

Late Modernist Architecture

Late modernist architecture generally refers to buildings designed from 1968 to 1980. It features bold shapes and sharp corners, often more defined than the earlier Brutalist architecture style.

Postwar Modernism in the United States (1945–1985)

The International Style became known in the U.S. in 1932. Many leaders of the German Bauhaus movement moved to the U.S. after the Nazis came to power. They played a big role in American modern architecture.

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Guggenheim Museum

-

The tower of the Johnson Wax Headquarters (1944–50).

-

The Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma (1956).

-

Solomon Guggenheim Museum, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1946–1959).

Frank Lloyd Wright continued to be a leading architect even in his old age. One of his unique later projects was the Florida Southern College campus, which he wanted to "grow out of the ground and into the light."

He also designed the Johnson Wax Headquarters and the Price Tower (1956). The Price Tower is unusual because it's supported by a central core, with the rest of the building hanging off it like tree branches.

In 1943, he was asked to design a museum for modern art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. His design was very original: a bowl-shaped building with a spiral ramp inside. It was finished in 1959, the year he passed away.

Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer

-

Story Hall of the Harvard Law School by Walter Gropius and (The Architects Collaborative).

-

The Stillman House Litchfield, Connecticut, by Marcel Breuer (1950).

-

The PanAm building (Now MetLife Building) in New York, by Walter Gropius (1958–63).

Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, moved to the U.S. in 1937 and became head of architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design. Marcel Breuer, who worked with him at the Bauhaus, joined him. They influenced many students who became famous architects. Their works include the U.S. Embassy in Athens and the MetLife Building in New York.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Less is More

-

Villa Tugendhat in Brno, Czech Republic (1928–30).

-

The Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (1945–51).

-

Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago (1956).

-

The Seagram Building, New York City, 1958, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe famously said, "Less is more." He directed the architecture school at the Illinois Institute of Technology from 1939 to 1956, making Chicago a center for modernism. He built new buildings for the Institute and high-rise apartments that became models across the country.

His major works include the Farnsworth House (1945–1951), a simple glass box that greatly influenced home design. The Seagram Building in New York City (1954–58) set a new standard for clean, elegant design with its glass and steel walls.

Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames

-

Eames House by Charles and Ray Eames, Pacific Palisades, (1949).

-

Neutra Office Building by Richard Neutra in Los Angeles (1950).

-

The Constance Perkins House by Richard Neutra, Los Angeles (1962).

Richard Neutra and Charles and Ray Eames were important home designers. The Eames House (1949) in California is famous. It's made of translucent and transparent panels on a steel frame, influenced by Japanese design. It was assembled very quickly.

Richard Neutra continued to build influential houses in Los Angeles, often using glass walls to blend indoor and outdoor spaces. His Constance Perkins House (1962) was a simple, affordable home built with inexpensive materials.

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and Wallace K. Harrison

-

Manhattan House by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (1950–51).

-

Lever House by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (1951–52).

-

Manufacturers Trust Company Building, by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, New York City (1954).

-

Beinecke Library at Yale University by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (1963).

-

United Nations Headquarters in New York, by Wallace Harrison with Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier (1952).

-

The Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in New York City by Wallace Harrison (1966).

Many famous modern buildings were designed by large firms like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). Their style was inspired by Mies van der Rohe. They designed many New York skyscrapers, including Manhattan House (1950–51) and Lever House (1951–52). Later, they built the Willis Tower in Chicago (1973).

Wallace Harrison was important in New York architecture. He helped design Rockefeller Center and was the chief architect for the United Nations Headquarters. He also designed the Metropolitan Opera House.

Philip Johnson: From Modern to Postmodern

-

The Glass House by Philip Johnson in New Canaan, Connecticut (1953).

-

The IDS Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by Philip Johnson (1969–72).

-

The Crystal Cathedral by Philip Johnson (1977–80).

-

The Williams Tower in Houston, Texas, by Philip Johnson (1981–1983).

-

PPG Place in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, by Philip Johnson (1981–84).

Philip Johnson (1906–2005) was a key figure in American modern architecture. He studied with Walter Gropius and was influenced by Mies van der Rohe. His own home, the Glass House (1953), was modeled after Mies's Farnsworth House.

Later, Johnson started to move away from strict modernism. His AT&T Building (1979) in New York City, with its broken top, is often seen as the start of Postmodern architecture.

Eero Saarinen: Sculptural Designs

-

The Gateway Arch in Saint Louis, Missouri (1948–1965).

-

Main building of the General Motors Technical Center (1949–55).

-

The Ingalls Rink in New Haven, Connecticut (1953–58).

-

The TWA Terminal at JFK Airport in New York, by Eero Saarinen (1956–62).

Eero Saarinen (1910–1961) designed buildings that looked more like huge sculptures. He used sweeping curves and shapes, like the wings of birds. In 1948, he designed the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, a huge stainless steel arch.

His TWA Terminal at JFK Airport in New York (1956–1962) is one of his most famous works. It has four curving concrete roofs that look like a bird about to fly. All the details inside, from benches to clocks, matched the building's style.

Louis Kahn: Monumental and Solid

-

The Salk Institute by Louis Kahn (1962–63).

-

Richards Medical Research Laboratories by Louis Kahn (1957–61).

-

The Kimball Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (1966–72).

-

The National Parliament Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–74).

Louis Kahn (1901–74) also moved away from the simple glass box style. He used concrete and brick to make his buildings look monumental and strong. His designs were inspired by many different styles.

Notable buildings by Kahn include the First Unitarian Church of Rochester (1962) and the Kimball Art Museum in Texas (1966–72). He also designed the Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (National Assembly Building) in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–74).

I. M. Pei: Modern Master of Museums

-

Green Building at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by I. M. Pei (1962–64).

-

The National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado by I. M. Pei (1963–67).

-

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York by I. M. Pei (1973).

-

East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., by I M. Pei (1978).

-

Pyramid of the Louvre Museum in Paris by I. M. Pei (1983–89).

I. M. Pei (1917–2019) was a major figure in late modernism. He studied with Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius. One of his early buildings, the Green Building at MIT, had a problem: strong winds made the doors hard to open!

Pei became famous for his museum designs. The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art (1973) and the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art (1978) were highly praised. His most famous project is the glass pyramid at the entrance of the Louvre Museum in Paris (1983–89). He chose the pyramid shape because it fit well with the old museum buildings.

Fazlur Rahman Khan: Engineering Tall Buildings

-

John Hancock Center in Chicago by Fazlur Rahman Khan used X-bracing.

-

Willis Tower in Chicago used the bundled-tube design.

Fazlur Rahman Khan (1929–1982) was an engineer who worked for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. He invented new ways to build very tall buildings using less material. He designed the 100-story John Hancock Center in Chicago, which used a special "trussed-tube" design.

He also designed the 110-story Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower), which was the tallest building in the world for many years. His "tube structures" are still used today in many skyscrapers over 40 stories tall, including the Burj Khalifa. He believed engineers should also appreciate art and people.

Minoru Yamasaki: Unique Skyscrapers

-

The Twin Towers of the World Trade Center (1973–2001) in Lower Manhattan by Minoru Yamasaki (1913–1986).

-

The Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and William Igoe Apartments Housing Project, in St. Louis (1955–1976).

-

The Century Plaza Towers in Los Angeles, California (1975).

-

One Woodward Avenue in Detroit, Michigan (1962).

Minoru Yamasaki (1913–1986) was an American architect known for his unique engineering solutions. He designed the 1,360-foot tall Twin Towers in New York City. He used very narrow vertical windows because he had a personal fear of heights.

For the Twin Towers, he created a special "Skylobby" elevator system. Instead of one huge elevator shaft, there were three separate systems serving different parts of the building. This saved a lot of space for offices. He also designed the Pruitt–Igoe Housing Project and the Century Plaza Towers.

Postwar Modernism in Europe (1945–1975)

-

Sainte Marie de La Tourette in Evreaux-sur-l'Arbresle, France by Le Corbusier (1956–60).

-

Royal National Theatre, London, by Denys Lasdun (1967–1976).

-

Auditorium of the University of Technology, Helsinki, by Alvar Aalto (1964).

-

University Hospital Center in Liège, Belgium by Charles Vandenhove (1962–82).

-

The Pirelli Tower in Milan, by Gio Ponti and Pier Luigi Nervi (1958–60).

-

The Fondation Maeght by Josep Lluis Sert (1959–1964).

-

Municipal Orphanage in Amsterdam by Aldo van Eyck (1960).

In France, Le Corbusier remained a top architect. His Sainte Marie de La Tourette convent (1956–60) was made of raw concrete, simple and without decoration.

In Britain, Denys Lasdun's Royal National Theatre (1967–1976) was made of raw concrete and had a blocky shape. In Finland, Alvar Aalto adapted modernism to the Nordic landscape, using wood. In Denmark, Arne Jacobsen designed both furniture and buildings.

In Italy, Gio Ponti and engineer Pier Luigi Nervi designed the Pirelli Building in Milan (1958–1960), which was Italy's tallest building for many years. The Spanish architect Josep Lluis Sert worked with Le Corbusier and designed the Fondation Maeght in France (1964).

Tropical Modernism: Adapting to Warm Climates

Tropical Modernism, also called Tropical Modern, mixes modern architecture with traditional building ideas from tropical places. It appeared in the mid-20th century in areas like Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

Architects used features like solar shading (to block harsh sun) and narrow corridors (to let cool breezes flow through). This style helped buildings stay cool in hot, humid weather. Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew were important in developing this style.

Latin America: A Modern Showcase

-

Ministry of Health and Education in Rio de Janeiro by Lúcio Costa (1936–43).

-

The National Congress building in Brasília by Oscar Niemeyer (1956–61).

-

The Cathedral of Brasília by Oscar Niemeyer (1958–1970).

-

The Palácio do Planalto, offices of the Brazilian president, by Oscar Niemeyer (1958–60).

-

São Paulo Museum of Art, MASP, by Lina Bo Bardi (1957–68).

-

The Colegio de México in Mexico City by Teodoro González de León and Abraham Zabludovsky (1976).

-

Inside the Luis Barragán House and Studio in Mexico City, by Luis Barragan (1948).

-

The Alfonso Caro Auditorium in UNAM, Mexico City, by Eugenio Peschard (1953).

-

Residencias del Parque in Bogotá, Colombia by Rogelio Salmona (1965–1970).

Latin America became a great place for modern architecture. Architects adapted modernism to the tropical climate and local ways of life.

Brazil became famous for modern architecture through the work of Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. Niemeyer helped design the United Nations Headquarters. Costa and Niemeyer also planned and built the new capital city, Brasília, between 1956 and 1961. Niemeyer designed the government buildings, including the President's palace and the National Assembly, with their unique shapes.

Mexico also had a strong modernist movement. Architects like Félix Candela specialized in concrete structures with unusual curved forms. Mario Pani designed the National Conservatory of Music. The Torre Latinoamericana (1956) was an early skyscraper in Mexico City that survived a big earthquake. Luis Barragan designed his own home with simple forms, pure colors, and lots of natural light. His house is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Asia and Australia: Modernism Across Continents

-

House of Kunio Maekawa in Tokyo (1935).

-

International House of Japan by Kunio Maekawa, Tokyo (1955).

-

Yoyogi National Gymnasium by Kenzo Tange (1964).

-

Sydney Opera House in Sydney, Australia, by Jørn Utzon (1973).

-

Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center, Baku, Azerbaijan by Zaha Hadid Architects (2007).

-

A modernist building in Pune, India.

After the war, Japan needed many new homes. Japanese architects mixed traditional and modern styles. Kunio Maekawa, who worked with Le Corbusier, designed his own house in Tokyo, combining old and new ideas.

Kenzo Tange designed many office buildings and cultural centers, including the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Its concrete roof hangs from steel cables.

The Danish architect Jørn Utzon designed one of the most famous modernist buildings: the Sydney Opera House in Australia (1973). Its five concrete shells look like seashells by the beach.

In India, modern architecture was encouraged after independence. Le Corbusier designed the city of Chandigarh. Important Indian modernist architects include BV Doshi and Charles Correa. In Sri Lanka, Geoffrey Bawa started Tropical Modernism.

Africa: Modern Designs in Diverse Climates

-

Tour de la nation, Tunis.

Modernist architecture in Ghana is also part of Tropical Modernism.

Some notable modernist architects in Morocco were Elie Azagury and Jean-François Zevaco.

Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, is famous for its modernist buildings from the time it was an Italian colony.

Preserving Modern Architecture

Many modern buildings and collections have been named World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. This includes the Rietveld Schröder House, the Bauhaus buildings, the White City of Tel Aviv, the city of Asmara, the city of Brasília, the Sydney Opera House, and some works by Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Organizations like Docomomo International and the World Monuments Fund work to protect and document modern architecture that is at risk.

See also

- Complementary architecture

- Contemporary architecture

- Critical regionalism

- Ecomodernism

- List of post-war Category A listed buildings in Scotland

- Modern art

- Modern furniture

- Modernisme

- New Urbanism

- Organic architecture

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |