Fallingwater facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fallingwater |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Stewart Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Uniontown |

| Built | 1936–1937 (main house), 1939 (guest house) |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style(s) | Modern, organic architecture |

| Visitors | about 160,000 (in the 2010s) |

| Governing body | Western Pennsylvania Conservancy |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-005 |

| Region | North America |

| Designated | July 23, 1974 |

| Reference no. | 74001781 |

| Designated | May 23, 1966 |

|

Pennsylvania Historical Marker

|

|

| Designated | May 15, 1994 |

Fallingwater is a famous house in Stewart Township, Pennsylvania. It is known for being built right over a waterfall! The famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed this unique home. It was a weekend getaway for the Kaufmann family.

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy now takes care of Fallingwater. They have operated it as a popular tourist spot since 1963. The conservancy also looks after the 5,000 acres of land around the house. Fallingwater is a National Historic Landmark. It is also part of a World Heritage Site that includes other buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Contents

What is Fallingwater?

Fallingwater is located in the Laurel Highlands of southwestern Pennsylvania. It is about 72 miles southeast of Pittsburgh. The house sits near Bear Run, a stream with a waterfall. It is close to Ohiopyle State Park.

Fallingwater is one of four buildings in this area designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The others are Kentuck Knob, Duncan House, and Lindholm House.

How is Fallingwater designed?

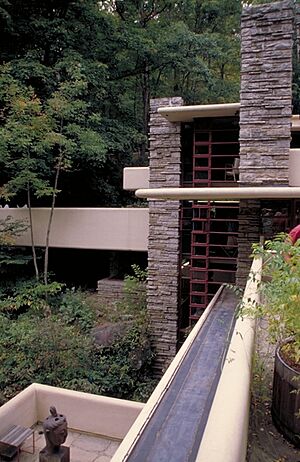

Fallingwater is named because it is built over the Bear Run stream. The main house is above a 20-30 foot waterfall. The stream does not flow through the house itself. It sometimes freezes in winter and dries up in summer. The house is built on layers of sandstone. It is not easily seen from far away because of the surrounding forest.

A guest wing is located on a hill north of the main house. It is connected by a curved outdoor path. There is also a visitor center with bathrooms and exhibit areas. The Barn at Fallingwater, built around 1870, is also nearby. The grounds include a small mausoleum for the Kaufmann family.

Who owned the land before?

In the 1890s, a group from Pittsburgh had a country club here. By 1909, it became the Syria Country Club. This club closed in 1913.

Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr., who owned Kaufmann's Department Store, started a summer retreat for his employees in 1916. Up to a thousand employees used it each summer. In 1922, Edgar and his wife Liliane built a simple cabin nearby. The Kaufmann family bought the entire site in July 1933.

How was Fallingwater built?

Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann's son, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., studied with Frank Lloyd Wright. Edgar Jr. became an apprentice at Wright's studio, Taliesin, in 1934. His parents met Wright that November. Many people believe Edgar Jr. was very important in the creation of Fallingwater.

Planning the design

Frank Lloyd Wright was 67 years old when he was hired in late 1934. He wanted to choose a site with unique features. Wright visited Bear Run and was excited by the landscape. The Kaufmanns wanted a large living space, at least three bedrooms, and a guest area. Edgar Sr. hoped to spend between $20,000 and $30,000.

Wright's plan included exposed cantilevers, which are parts of the building that stick out without support from below. He wanted the house to be on the northern bank of Bear Run. This would allow natural light into every room. The Kaufmanns expected the house to be downstream from the waterfall. This would let them see the cascades. But Wright wanted them to "live with the waterfall, not to look at it." So, he designed the house right above it.

Wright sent his first plans to Edgar Sr. in October 1935. The Kaufmanns loved the design. By January 1936, detailed drawings were ready. Edgar Sr. had engineers review the plans. They found structural issues and advised against building it. But Wright and Kaufmann went ahead.

Building the house

Edgar Sr. was very involved in the project. Wright visited every four to six weeks. Local workers, many without much experience, built the house. There were often disagreements between Wright, Kaufmann, and the builders. Wright cared more about how the house looked than about some building concerns.

Concrete and stone work

A nearby quarry was reopened in late 1935 for stone. Construction on the foundation began in April 1936. Workers poured concrete for the first-floor terrace in August 1936. Edgar Sr. secretly added extra steel bars to the concrete. Wright was very upset when he found out. He believed the extra steel would make the terraces too heavy.

After the concrete was poured, the first-floor terrace sank about 1.75 inches. Cracks also appeared. Wright said cracked concrete was normal, but Edgar Sr. was worried. By December 1936, five major cracks were found. A stone wall was even built under a terrace to help support it. Wright had this wall removed later.

Finishing touches

By early 1937, the inside of the house was being finished. Windows were installed. Wright suggested covering the outside with gold leaf, but this idea was rejected. He then chose a color like a dried rhododendron leaf, a shade of ocher. This waterproof paint was from DuPont.

The Kaufmanns moved into the house in November 1937. The main house was fully furnished by 1938. Wright named it "Fallingwater" around this time. He also designed a guest wing, which was finished in 1939. The total cost for the house and guest wing was $155,000. This was much more than the original budget.

Fallingwater as a home

The Kaufmann family used Fallingwater as their weekend home for 26 years. They would take the train and then be driven to the house. They invited famous guests like the artists Diego Rivera and Pablo Picasso, and the scientist Albert Einstein.

Fallingwater started showing problems soon after it was built. It leaked in 50 places. The terraces began to sag. Edgar Sr. even called it "Rising Mildew." Despite repairs, cracks kept coming back.

After World War II, the family spent winters in California. In the 1950s, posts were installed under the second floor to stop it from sagging. Windows cracked, and doors became hard to open. Liliane Kaufmann died in 1952, and Edgar Sr. died three years later. Their son, Edgar Jr., continued to use the house. He stopped the yearly structural checks. In 1956, the living room flooded during a storm.

Fallingwater as a museum

Opening to the public

Edgar Kaufmann Jr. decided to donate Fallingwater to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC) in September 1963. He wanted it to be a public museum. Many of Wright's other houses were being torn down or changed. The WPC took over the house on October 29, 1963. Edgar Jr. also gave money for the house's upkeep and educational programs.

The museum was dedicated to Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann. The WPC worked to make the house look as it did when the family lived there. They furnished the rooms with the Kaufmanns' belongings. Guided tours started in July 1964. Visitors could see most rooms. Edgar Jr. stayed involved with Fallingwater until he passed away in 1989.

Repairs and changes

The house's outside was repainted in 1972. A gift shop was added in 1973. The WPC planned a visitor center, which opened in April 1979. Sadly, it burned down two days later.

The visitor pavilion was rebuilt and reopened in 1981. By the 1980s, acid rain and freezing weather caused damage. Water leaked onto the terraces and roof. The ends of the terraces had sagged by 7 inches. The WPC spent a lot of money on repairs. They restored furniture and added waterproofing.

Big renovations in the 1990s and 2000s

Engineers found that the terraces' cracks were getting worse in the mid-1990s. They were at risk of collapsing. Temporary supports were installed in 1997. The WPC raised $6 million for major structural repairs. They used a method called "post-tensioning." This involved pulling strong steel cables through the beams.

Work began in late 2001. The outer end of the first-floor terrace was raised slightly. This post-tensioning cost about $4 million. It stopped further damage to the terraces. The WPC also fixed water damage and improved drainage. The house was connected to a city water system for the first time. These renovations were mostly finished in 2003.

Recent years

After the renovations in 2005, the WPC removed unwanted plants from the grounds. In 2010, they replaced 319 windows. In 2017, a statue was damaged during a rainstorm.

In 2019, plans for a $3 million waterproofing project were made. The museum closed temporarily in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Pennsylvania. It reopened for outdoor tours in June. In 2022, solar panels were installed to help power the house. The waterproofing project's cost doubled to $6 million. In 2024 and 2025, the WPC spent $7 million to fix leaks. The house remained open for tours during these repairs.

Fallingwater's architecture

Fallingwater is a great example of Wright's "organic architecture." This means it blends with nature. It is also seen as a Modern-style building. Wright was inspired by Japanese architecture. He wanted to make the house feel like part of its natural setting.

The main house has three stories. Wright wanted to blur the lines between inside and outside. He used the same materials for both. He also wanted people to feel breezes and hear the waterfalls inside. Fallingwater is made of local sandstone, reinforced concrete, steel, and plate glass. The wood inside is black walnut.

Outside the house

The outside of the house uses three colors. Gray for the sandstone, a light ocher for the concrete, and Cherokee red for the steel. Red was used because Wright thought it was a "color of life." The windows have metal frames painted Cherokee red. Some corner windows open inward.

The roof is covered with beige gravel. The house's chimney is made of stone and rises 30 feet. You reach the house by crossing a 28-foot bridge over Bear Run. There is a small fountain near the entrance. This was for washing feet after walking in the stream.

Terraces that float

Fallingwater has many cantilevered terraces. These are concrete slabs that stick out from the house. They are only supported at one end. Wright compared them to tree branches. They have low walls, called parapets, that are 26 inches high. This was much shorter than what is allowed today.

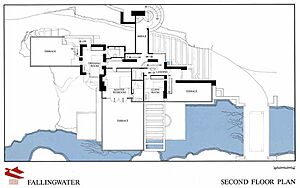

The main part of the house, with the living room, extends over the stream. It is supported by four large piers. The living room floor is made of stone tiles. Other outdoor terraces are on the east and west sides. Each bedroom also has its own outdoor terrace.

Inside the house

Fallingwater's floor plan is not perfectly symmetrical. It has about 2,885 square feet of indoor space. The walls, chimney, and piers are made of local sandstone. The floors have black-walnut wood and stone.

The house has four bedrooms. Wright designed the rooms to feel like they flow into each other. Hallways have low ceilings to create a cozy, cave-like feeling. Bedrooms are smaller to encourage people to use the terraces. Wright was 5 feet 8 inches tall. He designed some ceilings as low as 6 feet 4 inches.

Interior decorations include special lights and furniture. Many items are built-in or cantilevered. The rooms use indirect lighting, which was new for homes back then. Wright placed the toilets higher than usual. He believed a squatting position was healthier.

First floor fun

The first floor has the main entrance, the living area, and the kitchen. The living room is built over the waterfall. Its floor is waxed stone, like the stream below. The living room is a large space for living, studying, and dining. It has a fireplace with a hearth made of boulders. A large boulder even sticks out of the floor.

The living room has windows on three sides. It also has doors to the outdoor terraces. A special glass hatch in the living room floor covers stairs. These stairs lead down to Bear Run. The Kaufmanns kept this hatch open in summer. There is a shallow pool at the bottom of the stairs.

The kitchen is next to the living area. It is a practical space. Liliane Kaufmann did not use the kitchen much.

Upper floors and guest wing

The second floor has two bedrooms. The master bedroom is above the living room. It has custom shelves and a fireplace. There is also a guest bedroom. A gallery connects to a footbridge. This bridge leads to the guest wing.

The third floor has a bedroom that Edgar Jr. used as a study. Liliane used the third-floor terrace as a roof garden. The house also has a cellar with storage and a boiler room.

The guest wing is connected by a curved outdoor walkway. This path goes under a concrete canopy. It includes a small rock pool. The guest wing has a lounge, bedroom, and bathroom. The lounge has a stone fireplace. The guest room is next to an outdoor swimming pool.

Next to the guest house is a carport for four cars. Above the carport are three bedrooms and a bathroom for staff.

Art and furniture

Fallingwater has over 1,000 objects. The house did not have air conditioning or curtains until the 2000s. This, along with humidity, made the collection fragile.

Furnishings

Half of the house's furniture is built-in. Wright designed most of it. There are nearly 200 pieces, including wardrobes, chairs, and tables. Many items have walnut finishes to prevent moisture damage. The living room has a dining table that can seat 18 people.

The Kaufmanns bought other items, like Tiffany lamps. They also collected objects from Mexico. Most of the original furnishings are still there. However, some rugs and pillowcases have been replaced. The Kaufmanns sometimes disagreed with Wright's furniture ideas. They bought their own stools because Wright's designs were not stable.

Art collection

Wright gave the Kaufmanns six Japanese woodblock prints when the house was finished. The Kaufmanns chose the rest of the art. They liked collecting art from different cultures. The colorful artwork inside contrasts with the outside colors.

The collection includes works by Diego Rivera and Pablo Picasso. An 18th-century painting, Madonna and Child, is on the second-floor staircase. The house also has sculptures by Jean Arp and Jacques Lipchitz. After the WPC took over, more art was added.

Visiting Fallingwater

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy manages Fallingwater and the surrounding 5,000-acre Bear Run Natural Area. They offer tours from March to November each year. There are also weekend tours in December. Different tours cover different parts of the house. Some tours allow photos, others do not.

The conservancy runs the visitor pavilion. Young children can stay at the child-care center there. The WPC also sells items based on Fallingwater's designs. They even sold jewelry made from concrete removed during renovations. They offer educational programs for students and teachers.

How many people visit?

In its first two years as a museum, Fallingwater had 117,000 visitors. Many visitors are fans of Wright's architecture. Famous visitors have included Joan Mondale, Brad Pitt, and Angelina Jolie.

By 1975, over half a million people had visited. By 1982, one million people had seen the house. Around 120,000 to 160,000 people visit each year. By 2022, Fallingwater had welcomed 5 million visitors since it opened.

Fallingwater's impact

Fallingwater became one of the most talked-about modern buildings by the 1960s. It is known as the world's most famous private home not owned by royalty. Its fame helped Frank Lloyd Wright's career. He went on to design 200 more buildings.

What people think of it

Early praise

When Fallingwater was finished, it received great reviews. Time called it Wright's "most beautiful job." Even critics who usually disliked modern architecture praised it. Wright received a silver medal for its design in 1940.

In 1941, the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph called it a top example of modernism. Olgivanna Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright's wife, said it was "the most dramatic home my husband designed." When the house became a museum, the Pittsburgh Press described its "deeper beauty."

Modern views

Many critics praise how Fallingwater blends with nature. The Washington Post said it "interprets and adapts to its surroundings." The Guardian noted how it combines nature and modern architecture. Blair Kamin wrote that it "appears to be in complete harmony with nature."

Some critics have had mixed feelings. In 1997, The Baltimore Sun questioned its high maintenance costs. Some felt the low ceilings and dark wood made it feel like a basement. Others thought it was impractical for families.

Awards and recognition

American architects called Fallingwater one of the "seven wonders of American architecture" in 1958. In 1991, members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) voted it the "best all-time work of American architecture." The AIA also named it the "building of the century" in 2000.

Architectural Record called Fallingwater "the world's most significant building of the 20th century." Smithsonian magazine listed it as one of "28 Places to See Before You Die." In 2025, Time Out magazine ranked it among the world's most beautiful buildings.

Fallingwater in media

Fallingwater became famous in early 1938. This was after an exhibition and lots of media coverage. Many books and articles have been written about it. NBC made a TV episode about it in 1963. There have also been documentaries about the house.

Photographs of Fallingwater are very popular. Virtual tours have been created, including a 3-D tour in the mid-2010s. The house was even featured on a postage stamp in 1982. It inspired buildings in the 1959 film North by Northwest and the 1943 novel The Fountainhead.

Special designations

Fallingwater became a National Historic Landmark in 1966. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. In 2019, UNESCO added Fallingwater to the World Heritage List. It is part of "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright."

Exhibits and influence

Museums have hosted exhibits about Fallingwater. New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) had an exhibit in 1938. Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Art has also featured it. The Miniature Railroad & Village at Pittsburgh's Carnegie Science Center displays a model of Fallingwater.

Fallingwater's unique design was not often copied by other architects. However, it did inspire some buildings. These include an office in Philadelphia and a house in Canada.

See also

In Spanish: Casa de la cascada para niños

In Spanish: Casa de la cascada para niños