Taliesin (studio) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Taliesin |

|

|---|---|

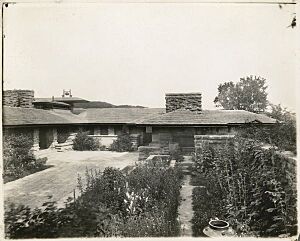

A portion of the building seen from the south in 2024

|

|

| Location | 5607 County Road C, Spring Green, Wisconsin, U.S. 53588 |

| Area | 37,000 square feet (3,400 m2) (interior of main building), 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2) (interior of all buildings), 600 acres (240 ha) (estate) |

| Built | 1911–1959 |

| Visitors | 25,000 (in 2023) |

| Governing body | Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-003 |

| Region | North America |

| Designated | March 14, 1973 |

| Reference no. | 73000081 |

| Designated | January 7, 1976 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Taliesin (pronounced tal-ee-ESS-in) is a famous house and studio complex. It is located near Spring Green, Wisconsin, in the United States. This large property, covering 600 acres (240 ha), was designed and lived in by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. It is a great example of the Prairie School style of architecture. Wright started building Taliesin in 1911 on land that belonged to his mother's family.

Wright designed the main Taliesin house and studio after leaving his first wife. He wanted the building to blend in with the flat plains and natural rock formations of Wisconsin's Driftless Area. The first building, which included areas for farming and art, was finished in 1911. The name Taliesin means "shining brow" in the Welsh language. It was first used for the building itself, which was built into the side of a hill. Later, the name was used for the entire property.

During Wright's time living there, two big fires caused major changes to the house. These different stages are called Taliesin I, II, and III. In 1914, after a tragic event where an employee set fire to the living areas and several people died, Wright rebuilt the residential part. He used this second version of the estate less often until 1922. In April 1925, an electrical fire badly damaged Taliesin II's living areas. Wright rebuilt it again later that year. He faced financial difficulties and lost the house for a short time in 1927. However, he was able to get it back the next year with help from friends. In 1932, he started a special program for architecture students at the estate. Taliesin III was Wright's home for the rest of his life. From 1937, he also spent winters at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. Many of Wright's most famous buildings were designed at Taliesin, including Fallingwater and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Wright also loved collecting Asian art and used Taliesin to store his collection.

When Frank Lloyd Wright passed away in 1959, he left Taliesin and its 600 acres (240 ha) property to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. This organization was started by him and his third wife in 1940. The Foundation managed the estate's upkeep until 1990. Then, a non-profit group called Taliesin Preservation Inc. (TPI) took over. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, TPI worked to fix damage that had happened over the years. In 2023, more than 25,000 people visited Taliesin. The Taliesin estate was named a National Historic Landmark in 1976. In 2019, it became a World Heritage Site as part of a group of eight buildings called "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright".

Contents

Exploring the Taliesin Site

Taliesin is located in Jones Valley, which is part of the Wisconsin River valley. This area, known as the Driftless Area, was not covered by ice during the last ice age. This created a unique landscape with many hills and deep river valleys.

The valley, about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of Spring Green, Wisconsin, was first settled by Frank Lloyd Wright's grandfather, Richard Lloyd Jones. His family came from Wales and moved to this part of Wisconsin in 1858 to start a farm. By the 1870s, Wright's uncles were running the farm. They invited Wright to work there during his summers.

Wright's aunts, Jane and Ellen C. Lloyd Jones, started a school called the Hillside Home School on the farm in 1887. They asked Wright to design the building, which was his first independent project. In 1896, his aunts asked him to build a windmill. The Romeo and Juliet Windmill was unusual but strong. By 1901, the school needed a bigger building, so Wright designed a new one. This became Hillside Home School II, and Wright later sent some of his own children there. Wright's last project on the farm was Tan-y-Deri, a house for his sister Jane Porter, finished in 1907. Tan-y-Deri means "under the oaks" in Welsh. Wright's family and their ideas greatly influenced him. He even changed his middle name to Lloyd to honor his mother's family.

Meaning of the Name Taliesin

When Wright decided to build his home in this valley, he chose the name of a Welsh poet named Taliesin. This name means "shining brow" or "radiant brow." Wright learned about this poet from a story about an artist's journey. The Welsh name also fit Wright's family background, as the Lloyd Jones family often gave Welsh names to their properties. The hill where Taliesin was built was a favorite spot from Wright's childhood. He saw the house as a "shining brow" on the hill, hoping it would be a safe place. Although the name first only referred to the house, Wright later used it for the entire property. Wright and others used Roman numerals (I, II, III) to tell the three versions of the house apart.

Early Days of Taliesin

Wright's home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois, was where he lived from 1889 to 1909. He built an architecture studio next to his Oak Park house in 1898. In Oak Park, Wright developed his Prairie School architecture style. In 1903, Wright began designing a home for Edwin Cheney. However, Wright and Cheney's wife, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, became close. They both separated from their spouses in 1909.

In October 1909, Mamah Borthwick met Wright in New York City. From there, they traveled to Europe. Wright worked on a collection of his designs, and Borthwick taught English. While in Italy, Wright was inspired by the Villa Medici in Fiesole, which was built into a hill with great views. In 1910, they wanted to return to the United States. Wright saw his family's land near Spring Green, Wisconsin, as a good place to build a new home. Wright returned to the U.S. in October 1910. He worked to get money to buy land for himself and Borthwick. On April 3, 1911, Wright wrote to a client asking for money to build a small house for his mother.

On April 10, Wright's mother, Anna, signed the deed for the property. By using his mother's name, Wright could buy the 31.5 acres (12.7 ha) property without drawing attention to his personal life. Later that summer, Mamah Borthwick, who had separated from her husband, quietly moved into the property. She stayed with Wright's sister, Jane Porter, at her home, Tan-y-Deri. However, a reporter discovered Wright and Borthwick's new home that fall. Their relationship became public news in the Chicago Tribune on Christmas Eve.

Taliesin I: The First Home

At Taliesin, Wright wanted to live in harmony with nature and his family history. He used only building materials found nearby. The house was designed to fit snugly against the hill, showing Wright's idea of "organic architecture". The rows of windows, a signature of his style, allowed nature to feel like it was part of the house. The smooth flow from inside to outside was very new for the time. This matched Wright's belief that architecture should be "of" the hill, not just "on" it. He once said, "I attend the greatest of churches. I spell nature with a capital N. That is my church."

Design and Features

Taliesin I was made of several connected buildings arranged in an "L" shape. These parts were linked by covered walkways called pergolas. There were three main sections: a long east section for the living areas, a long west section for farming, and an office section connecting the two. To the southwest, there was a courtyard with stables, service areas, and a garage. The one-story complex was reached by a road going up the hill to the back of the building. The entrance to the property was on County Road C. Iron gates stood between stone pillars topped with planters.

A covered entrance, called a porte-cochère, was above the main door of the living quarters. This provided shelter for cars. The living area included a bedroom and a combined living and dining room. The office section held the drafting studio and workroom. It also had an apartment for the main designer, which might have been for Wright's mother. Like other Prairie School designs, the house was, as Wright described, "low, wide, and snug." Wright also designed the furniture for most of his houses.

Wright chose yellow limestone for the house from a nearby quarry. Local farmers helped him move the stone up the Taliesin hill. The stones were laid in long, thin layers, just like they were found in nature. The plaster for the inside walls was mixed with a golden-brown color, making it look like the sand by the nearby Wisconsin River. The outside plaster walls were similar but mixed with cement, giving them a grayer color. Windows were placed so that sunlight could enter every room at different times of the day. Wright chose not to install gutters, so icicles would form in winter. The hip roof had a wooden frame with cedar shingles. These shingles were meant to turn silver-grey over time, matching the tree branches nearby. The finished house had about 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) of enclosed space.

Life at Taliesin I

After moving into Taliesin in the winter of 1911, Wright continued his architectural work. However, he found it hard to get new projects because of public attention on his personal life. Still, during this time, Wright created some of his most famous works, including the Midway Gardens in Chicago. He also enjoyed his hobby of collecting Japanese art and became a well-known expert.

Wright designed the gardens with help from landscape architect Jens Jensen. This included planting over a thousand fruit trees and bushes in 1912. Wright asked for many apple trees, including McIntosh and Golden Russet varieties. Among the bushes were gooseberry, blackberry, and raspberry plants. The property also grew pears, asparagus, rhubarb, and plums. Some of the orchard was destroyed during a railroad strike, so the exact number planted is unknown.

The fruit and vegetable plants were placed along the natural curves of the land. Wright also built a dam on a creek to create an artificial lake. This lake was filled with fish and water birds. This water garden, possibly inspired by gardens he saw in Japan, created a natural entrance to the property.

In 1912, Wright designed a "tea circle" in the middle of the courtyard. This circle was inspired by Jens Jensen's council circles and Japanese garden styles. Unlike Jensen's circles, Wright's tea circle was larger and had a pool in the center. It featured a curved stone bench with Chinese jars. The tea circle had two oak trees, though one fell in a storm in 1998. The tea garden also included a large plaster copy of a statue called Flower in the Crannied Wall.

The 1914 Fire and Aftermath

In August 1914, a tragic event occurred at Taliesin. An employee named Julian Carlton, who worked as a chef, set fire to the living quarters and caused the deaths of several people. Frank Lloyd Wright was away in Chicago at the time. Mamah Borthwick, her two children, and several staff members were at Taliesin. The fire quickly spread, destroying the living areas of the house.

Neighbors arrived to help put out the fire and search for the person responsible. The fire destroyed the living areas, but the farming wing and the drafting studio survived. The people who died were Mamah Borthwick, her children John and Martha, and several employees. Wright returned to Taliesin that night. He buried Mamah Borthwick on the grounds of the nearby Unity Chapel. Wright was deeply saddened by the loss.

The attack also had a big impact on Wright's architectural style. After this tragedy, his Prairie School period is considered to have ended.

Taliesin II: Rebuilding and New Beginnings

Soon after the tragic fire, Wright decided to rebuild the complex. Within a few months, he began construction, calling the new building "Taliesin II." He wrote about this, saying that rebuilding helped him deal with his sadness. The new complex was very similar to the original building and was built on the remains of Taliesin I. Like the first complex, Taliesin II was designed around terraces and courtyards. The dam, which had broken after the fire, was also rebuilt. Wright added an observation platform and later tried to make Taliesin self-sufficient with a hydroelectric generator. This generator was built in the style of a Japanese temple, but it eventually wore down and was removed in the 1940s.

Around Christmas 1914, while designing the new residence, Wright received a letter from Miriam Noel. They began a relationship, and by spring 1915, Taliesin II was finished, and Noel moved in with Wright. Wright's first wife granted him a separation in 1922, and he married Noel a year later. However, their life together at Taliesin became difficult due to Noel's unpredictable behavior. She left Wright by the spring of 1924.

In the new Taliesin, Wright worked to improve his public image. In 1916, he got a big project to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan. When the building survived a major earthquake in 1923 without damage, Wright's reputation was restored. Although he later expanded the farming area, Wright spent little time at Taliesin II. He often lived near his building sites abroad. Instead of being a full-time home, Wright used Taliesin like an art museum for his collection of Asian works. He only truly lived at Taliesin II starting in 1922, after his work on the Imperial Hotel was done.

On April 20, 1925, Wright returned from dinner and saw smoke coming from his bedroom. Most employees had gone home, leaving only a driver and one apprentice. Unlike the first fire, Wright was able to get help right away. However, the fire spread quickly because of strong winds. Despite efforts from Wright and his neighbors, the living quarters of Taliesin II were quickly destroyed. Luckily, the workrooms where Wright kept his architectural drawings were saved. Wright believed the fire started near a telephone in his bedroom, possibly due to an electrical surge during a lightning storm.

Taliesin III: A Lasting Legacy

Once again, Frank Lloyd Wright began rebuilding the living quarters of Taliesin. He wrote about this in his 1932 autobiography, calling the house "Taliesin III." He described how he found fragments of ancient art in the debris from the fire. He planned to weave these pieces into the new building, Taliesin III.

Wright faced many financial challenges after the destruction of Taliesin II. He had to sell many of his farm tools and even some of his valuable Japanese prints to pay off what he owed. In 1927, the bank took over Taliesin because of his debts, and Wright had to move away for a short time. Just before the property was to be sold, a former client, Darwin Martin, came up with a plan to save it. He created a company to raise money from Wright's future earnings. Many of Wright's former clients and students bought shares in this company, raising $70,000. The company successfully bought Taliesin for $40,000, returning it to Wright. Wright moved back to Taliesin by October 1928. Wright continued to work on Taliesin for the rest of his life. He also bought more land around it, creating a large property of 593 acres (240 ha).

Some of Wright's most famous buildings and ambitious designs were created at his studio during the Taliesin III period. These include Fallingwater, the world headquarters for S.C. Johnson, and the first Usonian house for Herbert and Katherine Jacobs. After World War II, Wright moved his main studio work in Wisconsin to the Hillside Home School. He then used the studio at Taliesin for meeting with new students and clients.

Design and Layout of Taliesin III

The Taliesin property today is located at 5481 County Road C in Wyoming, Iowa County, Wisconsin. All of Wright's buildings on the property cover about 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2) on 600 acres (240 ha) of land. Throughout Wright's life, he and his students kept making changes to Taliesin III. However, these changes were not always drawn on official plans. The construction was mostly done by Wright's students, who were often new to building. This sometimes led to small cracks and gaps in the structure. Wright also added several dams across the property to create lakes. The presence of Taliesin also influenced the design of public buildings in the nearby town of Spring Green.

The Main House

In its final form, the Taliesin III building is 37,000 square feet (3,400 m2). The main house is the northernmost building and is shaped like the letter "U," facing south. Unlike some of Wright's later designs, Taliesin III mostly uses rectangular shapes. Around the main house are fountains, gardens, and courtyards, similar to the first two versions. You reach the house by a driveway that goes around the hill to the main courtyard. Water from one of the estate's lakes is pumped up into the courtyard, filling its pools. The courtyard also has oak trees and a stone wall around it. One magazine wrote that the house "emerges from the hillside like a natural outcropping, rooted in the earth."

Wright's students were responsible for much of the building. They used recycled materials and new materials like plywood to build many parts. The outside of the house is covered with limestone from the area. Wright mixed stucco with Wisconsin River sand to give the walls a yellowish color. The house has intersecting hipped roofs with stone chimneys. The service wing, which wraps around one side of the hill, is the only part of the house that rises above the hill.

The inside of the house is not perfectly balanced, and the rooms are not as formally arranged as in Wright's later houses. Instead, the layout fits the shape of the land. Some rooms have low ceilings, about 6 feet (1.8 m) high, which is just a bit taller than Wright himself. The entrance area has low ceilings because Wright wanted people to move through it quickly. This area leads directly to the living room, which looks out over the Wisconsin River. The living room has large glass windows and a sloped ceiling. To the right of the living room is a "birdwalk" that extends out from the house. Wright's own bedroom has a low ceiling with high windows and a sliding glass wall that opens onto a terrace. There is also a studio with a sloped ceiling and a stone fireplace. Other rooms include an office and a sitting room.

Other Buildings at Taliesin

The Hillside Home School, located at the southern end of the complex, is designed in the Prairie Style. It has a 5,000 square feet (460 m2) drafting room for students. The Hillside Home School also has a theater with 100 seats. The modern Taliesin complex also includes the Midway Farm, built between 1938 and 1947. Although it's no longer a working farm, some buildings still exist, like a stone milk house and the Midway Barn. Wright's sister's house, Tan-y-Deri, is located up the hill from Midway Farm. Next to Tan-y-Deri is the octagonal Romeo and Juliet Windmill, a wooden structure 60 feet (18 m) tall. The Taliesin Dam is near the complex's entrance, and there are other houses on the grounds. Nearby is the Unity Chapel, where Wright was buried for a time.

The Taliesin Fellowship

Wright took over the nearby Hillside Home School when it faced financial trouble in 1915. In 1932, Wright and his wife started the private Taliesin Fellowship. Fifty to sixty students could come to Taliesin to learn from Wright. These students helped him develop the estate, especially when Wright had few other building projects. They renovated the old school gymnasium into a theater and built a drafting studio and dorms. Famous students included Paolo Soleri and Edgar Tafel.

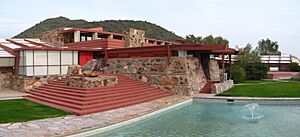

In 1937, Wright designed a winter home in Scottsdale, Arizona, which became Taliesin West. After it was built, Wright and the fellowship would travel between the two homes each year, spending winters in Arizona and summers in Wisconsin.

Wright saw the fellowship as a helpful educational program, not a formal school. He also worked to make sure that veterans returning from World War II could use their education benefits there. The town of Wyoming, Wisconsin, and Wright had a legal disagreement about whether the fellowship should be tax-exempt. Wright lost the case in 1954, but friends helped him raise money to cover the back taxes, and he decided to stay. The Taliesin Fellowship later became The School of Architecture.

Preserving Taliesin

In 1940, Frank Lloyd Wright, his third wife Olgivanna, and his son-in-law William Wesley Peters created the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Wright added a third story to the main house in 1943, which actually weakened the original structure. The Hillside School building caught fire in April 1952, and its theater and dining room were rebuilt. When Wright passed away on April 9, 1959, he was buried near the Unity Chapel. His body was later moved to Taliesin West in 1985. Ownership of both Taliesin and Taliesin West went to the Foundation. The Taliesin Fellowship continued to use the Hillside School as The School of Architecture at Taliesin. The fellowship allowed tours of the school but initially not of the house.

When the group spent two summers in Switzerland, rumors spread that they might sell the house. Instead, the fellowship sold some surrounding land to a developer. This led to the creation of a tourist complex with a golf course, restaurant, and visitor center.

Special Designations

In 1973, the Taliesin estate was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1976, it was recognized as a National Historic Landmark (NHL) District by the National Park Service. An NHL is a site considered to have "exceptional value to the nation." The important parts of the district include the landscape, Taliesin III, the courtyard's pool and gardens, Hillside Home School (with its drafting studio and theater), the dam, Romeo and Juliet Windmill, Midway Barn, and Tan-y-Deri.

In the late 1980s, Taliesin and Taliesin West were nominated to become a World Heritage Site. This is a UNESCO designation for places with special global importance. The U.S. government supported the idea, but UNESCO wanted a larger nomination with more of Wright's properties. In 2008, the National Park Service submitted Taliesin and nine other Frank Lloyd Wright properties for consideration. The United States Department of the Interior nominated the Taliesin estate again in 2015, along with nine other buildings. Finally, in July 2019, UNESCO added eight properties, including Taliesin, to the World Heritage List. This group is called "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright". Wisconsin Public Radio called the World Heritage designation "a triumph for Wisconsin," as two of the eight sites are in the state.

Restoration Efforts

1970s and 1980s

By the late 20th century, Taliesin had started to fall apart, even with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation's efforts. After being named an NHL, the organization received some federal money, but much more was needed for repairs. The house had also been damaged by an electrical fire in 1975. Some parts, like the Romeo and Juliet Windmill, were in even worse shape.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation did some repairs in the 1980s. These included strengthening the foundation, fixing fire risks, and insulating the ceilings. Although the Foundation still used the estate seasonally, Taliesin was closed to the public. In 1983, the Foundation began selling some of Wright's valuable documents to raise money for a large fund to restore the estate. These sales were debated, as some people did not want Wright's historical papers to be separated. During this time, most buildings, except the Hillside Home School, were closed to visitors.

In 1987, the National Park Service rated Taliesin as a "Priority 1" NHL, meaning it was seriously damaged or at risk. The main building was in poor condition, with cracked plaster, sinking foundations, and rotting wood. Some floors were warped, and a balcony had a large crack. Other buildings were also in bad shape. There was no heating system, and many parts were exposed to moisture and extreme heat. The National Trust for Historic Preservation also listed Taliesin as one of America's Most Endangered Places. Many of these problems were due to the way Taliesin was built, which was often experimental. Richard Carney, who led the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, began raising millions of dollars for repairs to both Taliesins.

1990s: Starting the Work

Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson created a group in 1988 to plan for Taliesin's preservation. This group estimated it would cost $14.7 million to fix the complex. Thompson then established Taliesin Preservation, Inc. (TPI), a non-profit organization, in 1990 to restore Taliesin. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation still owned the complex and worked with TPI. TPI received grants from the state government and other foundations. Taliesin began offering tours in mid-1992. Thompson suggested that the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority (WHEDA) fund the restoration with an $8 million bond issue. He thought the complex could attract many visitors, bringing in tourist money for Wisconsin. WHEDA approved a loan later that year. TPI also planned to spend $3.8 million on a visitor center. By the mid-1990s, the renovation was expected to cost about $24 million.

Early restoration work included fixing the foundation, addressing fire risks, and making emergency repairs. U.S. Senator Herb Kohl introduced a bill in July 1993 to provide another $8 million for Taliesin's restoration. Kohl and U.S. Representative Scott Klug also supported making Taliesin a National Park Service site, while the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation would still own it. TPI also sought donations to raise the remaining money. The first part of Taliesin to be restored, a terrace outside Wright's bedroom, was finished that October. Workers also supported parts of the complex that were at risk of collapsing. In the same year, due to damage to the Taliesin Dam, Wisconsin officials asked the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation to fix or remove it. TPI also bought the nearby Wright-designed Riverview Terrace Restaurant and turned it into a visitor center. The visitor center opened in June 1994. By then, TPI had raised $1 million in donations. Restoration work continued through the 1990s, even while the site was open to visitors.

After a severe storm on June 18, 1998, a large oak tree in the courtyard fell onto the house. This tree was the last of three that Wright had planted in 1911, and its fall caused $1 million in damage. Ten days later, heavy rains caused a mudslide near the main building. Following these events, workers made emergency repairs to the house and fixed damaged interiors and windows. By the late 1990s, the complex had about 50,000 visitors per year, fewer than TPI had hoped for. TPI also earned less money from tourism than expected and missed a loan payment in January 1999. The Wisconsin government eventually forgave most of the loan. That May, the federal government agreed to give Taliesin a $1.15 million grant if TPI raised an equal amount. This money would be used for interior restoration and drainage repairs. In the same year, TPI started asking for donations to restore the grounds and planned to raise $25 million for the renovation. Another storm in late 1999 caused a tunnel under the studio wing to collapse.

21st Century Efforts

According to the Wisconsin State Journal, preserving Taliesin was "fraught with epic difficulties." This was because Wright never thought of it as a series of buildings that would last forever. The studio wing's restoration was finished in August 2000, costing $400,000. By 2002, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation estimated it could cost up to $60 million to fully fix the Taliesin complex. At that time, workers were preparing to stabilize the hill under the house, as the hillside was causing the walls to lean and walkways to crack. To prevent more water damage, tarps had been placed on the ground. TPI had trouble raising money due to a weaker economy, and many of the complex's structural problems were not easy for the public to see, making fundraising harder. Preservation experts predicted the estate would be permanently damaged if not repaired within five to ten years.

A $900,000 project to improve Taliesin's drainage system was completed in 2004. The estimated cost of the restoration had grown to $67 million by 2005, with the main house alone costing $26 million. In the same year, a businessman named T. Denny Sanford donated $425,000 for Taliesin's restoration. These funds were used for roof repairs and planning future work. There were also plans to replace a bridge carrying Taliesin's driveway over a creek. In 2006, the Jeffris Family Foundation agreed to fund 25% of Tan-y-Deri's restoration, which was estimated to cost $828,000. More than $11 million was spent on Taliesin's restoration between 1988 and 2008. Funding renovations remained challenging because fewer people visited than expected. The Wisconsin State Journal reported in 2009 that TPI still needed to raise $50 million to restore the rest of the complex. TPI also began strengthening the house's structure, which had been weakened by the weight of the third-story guestrooms. The World Monuments Fund (WMF) added Taliesin to its 2010 World Monuments Watch to highlight the remaining structural issues.

By the early 2010s, workers had started repairing the house's foundation and lower level. The house was still open to the public, but only for guided tours. There were eight different types of tours because of Taliesin's long history. To celebrate Taliesin's 100th anniversary, TPI hosted a series of events in 2011. The complex remained at risk of damage, leading the WMF to add Taliesin to its 2014 World Monuments Watch again. In the mid-2010s, preservationists also began restoring Taliesin's gardens to look as they did in 1959. This project included adding specific flowers and rearranging orchards to match Wright's original plans. To attract visitors to Taliesin and other Wright-designed sites in Wisconsin, state lawmakers suggested giving money to the Wisconsin Department of Tourism for road signs promoting these sites. Taliesin was later included on the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail, which was created in 2017.

In 2018, Taliesin received a $320,000 grant for the Hillside theater's restoration. This project included improving drainage, updating mechanical systems, and adding rooms to the basement. The theater reopened in 2024, and its renovation cost $1.1 million. Workers also restored Taliesin's Midway Barn in the 2020s. The Wisconsin government's 2025–2027 budget, signed by Governor Tony Evers in July 2025, set aside $5 million for Taliesin's preservation.

Visiting Taliesin

TPI offers tours from May 1 through October 31 each year. Weekend tours of the grounds are also available in April and November. Other events and programs are offered at different times throughout the year. Tours of the house's inside are usually not given from November to April because Taliesin does not have a heating system. Wright had removed the furnaces after his Taliesin West complex was finished. Visitors are not usually allowed to stay overnight at the complex. In 2023, more than 25,000 people visited Taliesin. The Wisconsin Historical Society has rare old photographs of Taliesin in its collections.

See also

In Spanish: Casa Taliesin para niños

In Spanish: Casa Taliesin para niños

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Wisconsin

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Iowa County, Wisconsin

- Taliesin West

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |