Taliesin West facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Taliesin West |

|

|---|---|

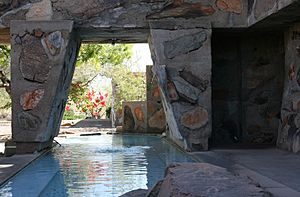

Pool and terrace outside the main building, facing east toward Taliesin West's vault and drafting room (2004)

|

|

| Location | Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S. |

| Area | 491 acres (199 ha) |

| Built | 1937 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style(s) | Organic architecture |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-007 |

| Region | North America |

| Designated | February 12, 1974 |

| Reference no. | 74000457 |

| Designated | May 20, 1982 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Taliesin West is a special place in Scottsdale, Arizona, designed by the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. It was his winter home and studio from 1937 until he passed away in 1959. The name "Taliesin" comes from Wright's first studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin.

Today, Taliesin West is the main office for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, a group that offers tours and events. It's recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a World Heritage Site, which means it's a very important place for history and architecture around the globe.

Wright and his students, known as the Taliesin Fellowship, started visiting Arizona in the winters of 1935. He bought the land in the McDowell Mountains in 1937. His students helped build the first parts of Taliesin West between 1938 and 1941. Wright kept adding to and changing the buildings during his lifetime. After he died, the fellowship continued to make changes, and Taliesin West became a popular place for visitors. In recent years, many parts of Taliesin West have been updated and restored.

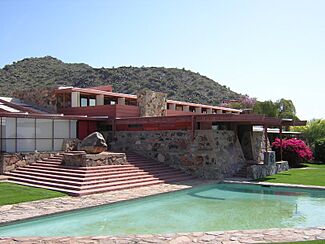

Taliesin West has many buildings connected by courtyards and paths. The walls are made from "desert masonry," a mix of local rocks and concrete. The roofs were originally made of wood and canvas. Inside, you'll see lots of triangles, hexagons, and designs inspired by nature. The main building includes a drawing room, kitchen, dining room, garden area, and the Wright family's home. There are also unique spaces like a kiva room and two places for performances. People often praise Taliesin West for how it uses natural materials and blends into the desert.

Contents

Exploring the Taliesin West Site

Taliesin West is located at 12621 North Frank Lloyd Wright Boulevard in Scottsdale, Arizona. The property covers about 491 acres (199 ha) and has flowers planted along its edges. It sits about 1,600 feet (490 m) above sea level, in a valley at the base of the McDowell Mountains. You can see the two highest peaks of the McDowell Mountains nearby: Thompson Peak and McDowell Peak.

The desert around Taliesin West has colorful volcanic rocks. From the estate, you can look out over the cities of Tempe and Chandler to the south, and the Phoenix Mountains to the southwest. A large canal, the Central Arizona Project, also runs near the property.

Before Frank Lloyd Wright bought the land, it was undeveloped. However, Native American people lived in the area for a long time. Some of the large rocks at Taliesin West have ancient petroglyphs (rock carvings) made by the Hohokam people. Wright found other Native American tools and pottery when he bought the land. One petroglyph, which means "handshake, friendship, and fellowship," later became the official logo for Taliesin West.

The History of Taliesin West

Frank Lloyd Wright had an architectural studio called Taliesin in Wisconsin, which he built in 1911. He started the Taliesin Fellowship in 1932, inviting young architects to learn from him by working on real projects.

How Taliesin West Began

Wright first visited Arizona in 1927. He returned in 1929 with some of his team to set up a temporary camp called the Ocotillo Desert Camp in Phoenix, Arizona. This camp was built with angled designs, which later inspired Taliesin West. Wright liked how the canvas tents at the camp felt "enjoyable and sympathetic to the desert," unlike the heavy houses he was used to. Also, Wright was getting older and found it hard to maintain his Wisconsin studio during the cold winters.

Finding the Perfect Spot

In late 1934, Wright decided to bring his students to the Arizona deserts for the winter. They stayed at a property called La Hacienda in early 1935. Wright wanted to buy his own land in Arizona. His wife, Olgivanna, preferred Arizona to Wisconsin. After getting sick in 1936, Wright's doctor told him to stay in the Arizona desert during the winter.

In December 1937, Frank and Olgivanna Wright found a great spot near McDowell Peak, about 26 miles (42 km) from Phoenix. Wright bought about 320 acres (130 ha) of land. He said the landscape was unmatched in its "sheer beauty of space and pattern." The land was cheap because people thought there was no water underground. Even though a local warned him, Wright paid to dig a well and found water deep down. The well cost more than the land itself, but it still provides water today.

Setting Up Camp and Planning

When Wright's students arrived at McDowell Peak in early 1938, there was nothing there: "no water, no building, nothing." They had to carry water from miles away and ration it for washing. They also had little money and ate simple meals. There was no phone service, and they used a portable power generator.

Wright decided to build the camp on a flat area near the base of McDowell Peak. The first students built their own tents. The Wrights stayed in a temporary wooden and canvas home called Sun Trap, which was inspired by the Ocotillo camp.

Wright started drawing plans for permanent buildings soon after. He wanted the buildings to blend with the desert, as if they grew from the ground. He didn't use traditional blueprints; instead, he often drew plans one day and had students build them the next. The final plans included a drawing room, a courtyard, an office, the Wrights' home, and workshops, all arranged around a covered walkway.

Building Taliesin West

Wright's students spent about five months each year building at Taliesin West. They faced challenges like digging foundations in the dry land and dealing with rattlesnakes and heavy rains. Most building materials, except for cement, came from the surrounding area. Wright decided to build the walls from local rocks mixed with cement, poured into wooden frames. The roofs were made of canvas sheets stretched over redwood frames. The interiors were decorated with colorful local quartzite rocks. Wright even moved some ancient petroglyphs to show respect for their original meaning.

The first building was a vault. Then, students built the masonry walls for the vault and kitchen. By early 1939, they were also building the drawing room, dining room, kiva, sleeping areas, and Wright's office. Many of these rooms were finished by 1940. The main complex was mostly complete by early 1941, though Wright always saw it as a work in progress.

Wright's Time at Taliesin West

The Arizona complex became known as "Taliesin West," to distinguish it from the original "Taliesin East" in Wisconsin. Wright designed many famous buildings while at Taliesin West. Up to 100 students worked there during the winters, learning by doing, as Wright believed. They followed a strict schedule, starting with breakfast at 6:30 a.m. Students took turns with tasks like cooking and gardening. A bell tower signaled meal times. Wright was a demanding teacher, but many students felt learning from him was worth it. On weekends, tourists could visit for a small fee.

Changes in the 1940s

Wright kept changing Taliesin West. Before World War II, he planted native cacti. During the war, fewer changes were made as some students joined the military. The complex was largely unused until 1945.

After the war, Wright started using new materials like glass, replacing some of the canvas and wood. His wife, Olgivanna, asked for glass to be installed so they could watch storms from inside. Wright added glass to the garden room and drawing studios. He also expanded the dining room. The original wood frames and fabric roofs wore out quickly in the hot summers, so they were replaced. The Sun Trap, the Wrights' first temporary home, was taken down in 1949 and replaced with the Sun Cottage for their daughter, Iovanna. Air conditioning was added so the buildings could be used in the summer.

In the 1940s, Wright also fought against overhead power lines because he thought they were ugly. He even contacted the U.S. president, Harry S. Truman, but the lines were still installed. Wright then moved the main entrance and living room.

Changes in the 1950s

In the early 1950s, the original theater (the kiva) became a library. The Cabaret Theatre was built behind Wright's office. Students often watched movies or live shows there on weekends. Taliesin West also got connected to Scottsdale's electrical grid by 1952. Olgivanna hosted gatherings for followers of the philosopher George Gurdjieff during winter weekends.

In 1954, Wright moved his firm's main office from Wisconsin to Taliesin West. Work began on a larger theater for musical performances. By 1957, a music pavilion was completed. Students listened to music there after dinner, and it hosted festivals. In 1959, Wright planned an orchard. When he passed away in Wisconsin that April, a memorial service was held for him at Taliesin West.

After Wright's Passing

After Wright's death, his son-in-law, William Wesley Peters, formed Taliesin Associated Architects, based at Taliesin West. Wright's architectural school also continued there. Olgivanna Wright managed Taliesin West, approving all major changes. Iovanna continued to live in the Sun Cottage and choreographed performances. The Cabaret Theatre hosted formal dinners and movie nights. Students had a busy schedule of lectures, construction, and design work.

More and more tourists visited Taliesin West after Wright's death, even though the fellowship didn't advertise it. Tours included slideshows and photos of Wright. Famous visitors included politicians, artists, and actors.

The 1960s and 1970s

Wright's students kept changing Taliesin West, adding steel and glass. In the 1960s, power lines were installed near the complex despite Olgivanna's protests. A fire destroyed the original music pavilion in September 1963, causing a lot of damage. Students quickly rebuilt it using one of Wright's old designs. Smoking was banned afterward. The music pavilion reopened in April 1965.

By the mid-1960s, Taliesin West had 1,500 visitors each month. In July 1966, another fire destroyed some dormitories, which were rebuilt with steel frames. Fiberglass roofs were added to other areas, replacing temporary materials. By 1967, almost every part of the main building had been replaced. Students also dug another well.

In 1970, the guest terrace was rebuilt with a steel frame. Taliesin West became part of Scottsdale in 1972. New bedrooms, a clinic, and a tower room were built. The Fellowship Pool was also added. The Arizona government provided some money for maintenance.

The 1980s

By the early 1980s, Taliesin West had about 40,000 to 50,000 visitors each year. Olgivanna continued to host social events like teas and performances. Students built a ticket booth, bookstore, reading room, and dormitory. When Olgivanna passed away in 1985, she had wanted Frank's remains moved to Taliesin West. Despite family objections, his remains were moved from Wisconsin to Scottsdale in 1985.

In the mid-1980s, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation started making digital copies of Wright's old documents. They also planned a study center and archive building. To raise money for repairs, the foundation got permission to build a housing development, Taliesin Gates, next to the complex. This also helped protect Taliesin West from the fast-growing Scottsdale suburbs.

The 1990s and 2000s

In the early 1990s, the garden room was renovated, and Wright's archives were moved to a special climate-controlled warehouse. A study suggested that Taliesin West could attract 250,000 visitors a year if a visitor center was built. Scottsdale officials approved funding for the center, but construction was delayed. Visitor numbers increased to 72,000 annually by 1996.

In 1998, the roofs of the garden room, office, and drawing room were rebuilt with acrylic panels. Offices for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation were created. A documentary about Wright's work increased visitors even more. By the early 2000s, the foundation planned a visitor center to increase annual visits to 200,000.

In 2003, the Wright Foundation received grants for restoration. An architect studied the property and estimated it needed $30–60 million in renovations. Wright's bedroom was restored in 2004. In 2006, the foundation sought to protect parts of its campus as a historic site, which was approved in 2008. Attendance dropped during the late 2000s recession but recovered in the 2010s.

The 2010s to Today

The Wright Foundation began renovating the living room in the early 2010s. They also started installing solar panels in 2012 to save energy. In 2014, an architect was hired to create a master plan for Taliesin West, which needed new roofs, mechanical systems, and repairs. The master plan, announced in 2015, focused on restoring the original buildings and fixing damaged parts. The foundation also planned to keep part of the complex as an educational campus.

To attract local visitors, the Wright Foundation expanded its education programs and hosted performances in the late 2010s. They received grants for upgrades and new technology.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Taliesin West was closed for much of 2020. During this time, several areas were restored, including the dining cove. The School of Architecture moved out of Taliesin West in 2020. Group tours restarted in March 2021, and the garden room was restored to its original look. The foundation also began replacing roof panels, making accessibility upgrades, and fixing old pipes. In 2024, a new master plan for renovations was started.

The Architecture of Taliesin West

Taliesin West has many buildings connected by courtyards and paths, often lining up with the desert landscape. It includes Wright's office, a drawing studio, living spaces, classrooms, and shared areas. The buildings are inspired by the desert's natural shapes. Wright wanted them to look "sharp, clean and savage," like the surroundings.

Wright liked using materials found nearby, such as local rocks and wood from northern Arizona trees. He also used cotton grown in the state for fabric. He said, "There were simple characteristic silhouettes to go by, tremendous drifts and heaps of sunburned desert rocks were nearby to be used. We got it all together with the landscape…" The design has few straight vertical lines or perfect right angles. Instead, it features sloped walls and slanted pillars, reflecting the nearby mountains. Wright said Arizona needed its own architecture with "long, low, sweeping lines, uptilting planes."

Wright decorated Taliesin West with art, especially Native American and Asian pieces. Olgivanna chose the colors, including 57 shades of pink, plus yellow and green. Inside, rooms are painted in shades of red, including Wright's favorite, a reddish-brown called Cherokee red.

Main Buildings

Taliesin West has three main buildings: the workshop, Wright's office, and the main building. Each building is designed using a grid of 16-by-16-foot (4.9 by 4.9 m) squares, and parts of the buildings meet at 45-degree angles. The workshop is the westernmost building. The main building is to the southeast of the workshop. Wright's office and studio are north of the main building. The Cabaret Theatre, music pavilion, and other workshops are next to the office and studio.

Outside the Buildings

The walls are made of local desert rocks stacked inside wooden frames and filled with concrete. This material was called "desert masonry." Students would label rocks by how many people it took to lift them. The flat sides of the rocks faced outward, and concrete was poured between them. The foundations are made of cement to handle extreme temperatures. The outside walls also have ramparts that blend into the landscape.

Most stone walls lean inward at a 15-degree angle. They are usually 2 to 10 feet (0.61 to 3.05 m) tall. The angled walls look like the nearby mountains and create shadows throughout the day. The building frames were originally redwood but later included reddish-pink steel. The walls also have decorations, like Chinese ceramic panels from a hotel in Tokyo and redwood cubes. Some rocks have triangular carvings, inspired by grooves Wright saw in nearby canyons.

Wright wanted Taliesin West to feel like a camp, calling the buildings "glorified tents." The roofs were originally canvas panels, angled at 15 degrees. These canvas sheets let natural light and air into the rooms. However, they leaked and wore out quickly in the summer heat. Wright and the fellowship later replaced them with fiberglass, plastic, and then acrylic panels in 1998.

Inside the Buildings

Taliesin West has about 50,000 square feet (4,600 m2) of space. The rooms are designed to get lots of natural light and stay comfortable. Triangular and hexagonal shapes are used everywhere, along with nature-inspired designs. The furniture is simple and organic, and the Wrights often moved it around.

The main building has a path with an open pergola that connects all the rooms. The pergola is sunken about 5 feet (1.5 m) and partly covered by trellises. Fireplaces are found throughout, and natural light fills the rooms. The drawing room, kitchen, and dining room are the main areas. The drawing room is at the northwest corner. The kitchen and dining room are in the center. The Wrights' apartments and a garden room are at the southeast corner. Originally, each main room was open to the outside on at least one side, allowing air to flow through.

Work Areas

Wright's office is just past the entrance. It has a see-through ceiling, like the original canvas roofs. It also had slanted walls and a large drawing table. After Wright's death, it became a reception room.

South of the office is the drawing studio, built from 1938 to 1941. It's a long, rectangular room, over 100 feet (30 m) long, with space for 60 worktables. It's an open workspace filled with natural light, and its tent-like design lets air move through. The ceiling slopes from 6 to 13 feet (1.8 to 4.0 m) high. At one end is the vault, where Wright's drawings were kept. The vault is now a computer lab.

Living Spaces

A long hallway separates the living areas and the drawing studio. It connects the pergola to Sunset Terrace. This hallway was originally the entrance to the dining room and the Wrights' home. The dining room (now the board room) is 40 by 28 feet (12.2 by 8.5 m) and has a large stone fireplace. Three of its walls are low, letting sunlight in. A sculpture of a dragon stands outside. Above the hallway, kitchen, and dining room is a guest terrace with several bedrooms. A bell tower is between the dining room and the drawing studio. Other bedrooms for students were located east of the dining room.

The Wrights' living area included a bathroom, kitchen, three bedrooms, a garden room, and a small dining area. The bedrooms faced east, and the garden room faced south. The garden room, which was the family's living room, is 56 by 34 feet (17 by 10 m) long. It has a sloped roof and a fireplace. Inside, you can find a statue of the Chinese goddess Guanyin and a bust of Wright.

The family's private rooms were small. For example, Frank Lloyd Wright's bedroom was only 11 by 11 feet (3.4 by 3.4 m). These rooms contained Japanese art and copies of Wright's books. The private dining area had a sculpture of Maitreya, the future Buddha.

Other Buildings

Next to the students' courtyard is a special masonry room called the kiva. It was named after a Pueblo Native American kiva and is partly underground. The kiva was once connected to the Wrights' living area by a wooden bridge over a hexagonal reflecting pool. A newer stone bridge and a water tower are there now. The kiva has windows near the top, just above ground. It has been used as a library, classroom, and conference space.

Next to Wright's office is the Cabaret Theatre, a performance space built in the early 1950s. It's a rectangular room built into the ground, with about 100 tiered seats and counters. The walls and ceiling are made of desert masonry and concrete. It has a projection booth and a fireplace. The theater contains a bust of the Buddha and a wooden carving from Southeast Asia.

East of the Cabaret Theatre is a music pavilion with 135 seats. Unlike other buildings, this one has a steel frame with plastic panels, rebuilt after a fire in 1964.

The Sun Cottage is east of the main buildings. It has an atrium and is connected by a bridge. It replaced the Wrights' first Sun Trap. The Sun Cottage has slanted desert-masonry walls with glass windows and an exposed steel-beam roof. It included a living room, kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom for Iovanna Wright, plus guest rooms.

There are other buildings too. The Pfeiffer House and a hexagonal women's dormitory are on the property. First-year students of the School of Architecture used to live in small tents nearby. In the late 20th century, there were 70 to 80 such tents. Students had to design their tents, and they had to take them down after graduating.

Courtyards and Terraces

The estate has many plants, pools, and sunken gardens. Rocks with petroglyphs are part of the buildings or placed around the complex. A parking lot is southwest of the workshop and Wright's office. An open courtyard leads from the workshop to the main building. This court has a stone tablet with "Taliesin West" and a light tower.

South of the open courtyard is a terrace called Sunset Point or Sunset Terrace. The main building's dining and drawing rooms wrap around Indian Rock Terrace. This terrace has a stepped pyramid topped with a boulder that has petroglyphs. A triangular pool is in front of Indian Rock Terrace. The pool was meant to be a water supply in case of fire and is fed by groundwater from Taliesin West's original well.

The students' courtyard is at the southeast corner of the main building, surrounded by their bedrooms. A sculpture garden with art by Heloise Crista, a former student, is also there. A citrus grove stands northeast of the main building.

Managing Taliesin West

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation manages Taliesin West. This group was started in 1940 to keep Wright's work and ideas alive. It became a nonprofit organization in 1983. The foundation owns the trademark for the Taliesin West name.

The foundation offers tours of Taliesin West, which vary in length and detail. Visitors are allowed to touch objects inside, which is different from most attractions. There are also virtual tours. Taliesin West hosts public events like day camps, movie nights, and lectures.

Taliesin West used to store the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation's archives, which were hard for researchers to access. In 1985, the foundation and the J. Paul Getty Trust started making copies of about 21,000 documents to share with scholars. The archives were moved to the Museum of Modern Art and Columbia University in New York City in 2012. The archive includes thousands of drawings, photos, and letters.

The Wright School of Architecture operated at Taliesin West until 2020, when it moved to the nearby Cosanti studio. From October to May, students stayed at Taliesin West, and for the rest of the year, they worked at the original Taliesin in Wisconsin. Since 2022, the foundation has run the Taliesin Institute, which offers classes at both locations.

The Impact of Taliesin West

What People Think About It

When Taliesin West was first built, newspapers said it was a mix of Mayan, Egyptian, and Japanese styles. The Arizona Republic wrote that it "cannot be compared accurately to any other building in the United States" and that it blended with the landscape. One writer said the materials, like glass walls and canvas roofs, "bring the outdoors in...with startling and exciting results."

In 1964, a writer said all the buildings at Taliesin West were "a unit in the entire design—a great tent," and that they were "in completeness with nature." Another writer noted that it "operates as if [Wright] still were guiding it." A Boston Globe writer said the building was "impossible to photograph satisfactorily" because its sharp edges meant there was no clear front or side. In 1981, a writer called the structures "innovative variations on parallelograms and trapezoids."

In 1993, a writer said the buildings showed respect for Wright's style. However, Paul Goldberger of The New York Times felt Taliesin West had an "oddly worshipful, almost cultlike quality," because students spoke of Wright with such respect. A reporter in 1998 called Taliesin West "one of the purest expressions of Frank Lloyd Wright's vision," because he built it on undeveloped land without client demands. Another reporter described it as "one part desert camp, one part cave and one part fleet of ships."

The writer Neil Levine said Taliesin West was "angular [and] rough" with raw-looking materials, unlike Wright's smooth concrete design for Fallingwater. The architect Philip Johnson called Taliesin West "the essence of architecture" but also said it might look like "a meaningless group of buildings" to those unfamiliar with Wright's work. Many critics noted that the buildings' natural, temporary feel had changed over time due to additions like air conditioning, glass ceilings, and steel beams.

Media and Exhibitions

Taliesin West was shown in a 1955 film about modern U.S. buildings and in a 1957 TV special. It was also featured in a 1972 TV special called "Taliesin West." Several books have been written about the complex. It was even shown in a children's book and on baseball cards featuring historic sites. A model of Taliesin West was displayed at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1940.

Historic Designations

Taliesin West received the American Institute of Architects' Twenty-five Year Award in 1973 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. It was further named a National Historic Landmark (NHL) in 1982, recognized as "one of the first major works during the last quarter-century of [Wright's] life." It was the 25th National Historic Landmark in Arizona and the first in the state specifically for its architecture. In 2006, part of Taliesin West was designated a historic preservation site by the city of Scottsdale.

In the 1980s, Taliesin and Taliesin West were nominated to become a World Heritage Site, a special UNESCO designation for places of global importance. UNESCO initially wanted a larger nomination with more of Wright's properties. In 2008, the National Park Service submitted ten Frank Lloyd Wright properties, including Taliesin West, to a list for World Heritage status. Finally, in July 2019, Taliesin West and seven other properties were added to the World Heritage List under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright."

See also

In Spanish: Taliesin West para niños

In Spanish: Taliesin West para niños