Hohokam facts for kids

The Hohokam were an ancient culture that lived in the Southwest of North America. This area is now parts of Arizona, United States, and Sonora, Mexico. They lived there between 300 and 1500 AD. Some experts think their culture might have started even earlier, around 300 BC.

Archaeologists are still debating if all Hohokam communities were connected or if they were separate groups. Local stories say that the Hohokam people might be the ancestors of today's Pima and Tohono O'odham people who live in Southern Arizona.

No one is sure exactly where the Hohokam culture came from. Most archaeologists believe it either grew locally or was influenced by people from Mesoamerica (like ancient Mexico). It was also shaped by the Northern Pueblo culture. Hohokam towns were on important trade routes. These routes went far, reaching the Great Plains in the east and the Pacific coast in the west. Many people moved into Hohokam areas. Some towns, like Snaketown, became big trading centers.

Living in the hot Sonoran Desert was a big challenge for the Hohokam. Even with trade, they focused on being self-sufficient and using local resources.

In modern-day Phoenix, the Hohokam are famous for their huge irrigation systems. Their network of canals in the Phoenix area was the most complex in the Western Hemisphere before Europeans arrived. Parts of these old canals have been fixed up and are still used today by the Salt River Project to bring water to the city. The original canals were just dirt ditches and needed constant care. When the Hohokam society ended, these dirt canals fell apart. Later, European-American settlers either filled in some canals or rebuilt them, like the Mormon pioneers did near Mesa.

The National Park Service says the word Hohokam comes from the O'odham language. Archaeologists use it to describe the groups of people who lived in the Sonoran Desert. Some archaeologists prefer to call them "Oasisamericans," seeing ancient Arizona as part of the wider Oasisamerica tradition. Still, the Hohokam are known as one of the four main cultures of the American Southwest and Northern Mexico.

There are a few ways to spell the name, like Hobokam, Huhugam, and Huhukam. While they seem similar, they have different meanings. In the 1930s, archaeologist Harold S. Gladwin used huhu-kam (which he thought meant "all used up" or "those who are gone") to describe the culture he was digging up. Later, in the 1970s, another archaeologist translated huhugam as "that which has perished." However, huhugam actually refers to past human life, not just old objects or ruins. So, the archaeological term Hohokam is different from huhugam, which is about respecting ancestors.

Contents

Overview

Hohokam society was mainly found along the Gila and lower Salt River in the Phoenix area. This central area was called the Hohokam Core. The Hohokam Periphery included nearby areas where their culture spread. Together, these formed the larger Hohokam Regional System in the northern Sonoran Desert of Arizona. The Hohokam also reached into the Mogollon Rim.

The Hohokam Core was located along rivers, which was a great spot for trade. They traded with the Patayan people to the west, the Trincheras of Mexico to the south, the Mogollon culture to the east, and the Ancestral Puebloans to the north. From 900 to 1150 CE, the nearby Chaco society also helped increase trade across the region. Goods traveled throughout the Colorado Plateau, northern Arizona, and the Phoenix area.

By 1300 CE, the Hohokam irrigation systems supported the largest population in the Southwest. Archaeologists found evidence in the Tucson Basin that a group living there as early as 2000 BCE might be the ancestors of the Hohokam. This older group grew corn, lived in villages all year, and had advanced irrigation canals.

The Hohokam used water from the Salt and Gila Rivers to build simple canals with weirs for farming. Between 800 and 1400 CE, their irrigation networks were as complex as those in ancient Egypt or China. They built them with simple tools, making sure the water flowed just right to prevent erosion. The Hohokam grew cotton, tobacco, corn, beans, and squash. They also gathered many wild plants. Later, they used dry-farming methods, mostly to grow agave for food and fiber. Their farming skills were key to living in the harsh desert. They helped small farming groups come together into larger towns.

Early Hohokam homes were usually rectangular pithouses, dug about 40 cm (16 in) into the ground. They had plastered floors and a clay fireplace near the entrance. By 600 CE, a unique Hohokam building style appeared, similar to Mesoamerica. This included ballcourts that were also used for gatherings and trade. By 1150 CE, pithouses were replaced by above-ground buildings with central courtyards. By 1200 CE, they started building rectangular platform mounds.

Hohokam burial customs changed over time. However, burning the dead (cremation) was a key part of the Hohokam Core culture. Archaeologists use cremation to understand trade or movement of people between communities. For example, the Mogollon people also used cremation. At first, the Hohokam buried their dead in a bent position, like the Mogollon. Later, they started cremating their dead, similar to the Patayan culture to the west. Cremation remained the main practice until about 1300 CE.

History

Hohokam history is divided into periods based on big cultural changes. Archaeologists use two main ways to describe these periods. One way, called Gladwinian, uses names like Pioneer, Colonial, and Sedentary. The other way, Cultural Horizon, is like the system used in ancient Mexico. It tries to avoid any bias in the names.

These historical periods mainly apply to the Hohokam Core Area around Phoenix. In other areas, called Hohokam Peripheries, local names are often used. This is because these communities were also influenced by their Ancestral Puebloan and Mogollon neighbors.

Pioneer/Formative Period (AD 1–750)

Early Hohokam people were farmers of corn and beans. They started small villages along the middle Gila River. These villages were near good farming land, and dry farming was common. They dug water wells, usually less than 3 meters (10 ft) deep, for drinking water. Their early homes were built from bent branches, covered with twigs, reeds, and thick mud.

Between 300 and 500 AD, the Hohokam improved their farming skills. They got new plants, probably through trade with people from modern Mexico. These included cotton, tepary beans, and different kinds of squash. They also started growing agave on rocky, dry land around 600 AD. Agave became a major food source. They also improved their canals to get more river water for irrigation.

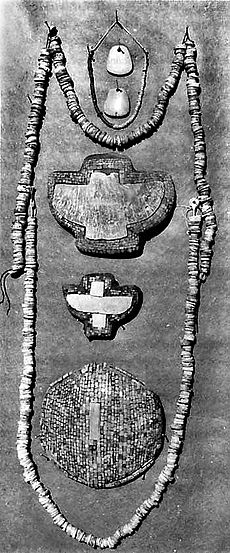

Evidence of trade includes turquoise, shells from the Gulf of California, and parrot bones from central Mexico. They used stone manos and metates to prepare seeds and grains. Pottery appeared before 300 AD. They made plain brown pots for storage, cooking, and holding cremated remains. They also made clay figures of humans and animals, and incense burners for rituals.

Colonial/Preclassic Period (750–1050/1150)

This period was a time of great growth. Villages became larger, with groups of houses sharing a common courtyard. Some larger homes and more decorated grave goods suggest that some people had higher social status. Farming areas and canal systems grew, and they started producing tobacco and agave. Mexican influence became stronger.

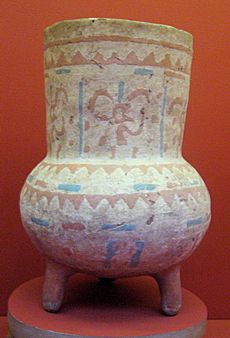

In bigger communities, the first Hohokam ball courts were built. These were important places for games and ceremonies. Pottery became more colorful, with a special red-on-buff style.

Sedentary Period (950–1050/1150)

The population continued to grow, leading to more changes. Irrigation canals became larger and needed more upkeep. More land was farmed. House designs changed to stronger pit-houses, covered with caliche adobe. Villages grew around shared courtyards, showing more community activities. Large ovens were used to cook bread and meat for everyone.

Crafts became much better. By about 1000 AD, the Hohokam were the first to master acid etching on shells. They made jewelry from shell, stone, and bone, and carved stone figures. Cotton weaving also became very popular. Red-on-buff pottery was made widely.

This growth meant more organization was needed, and perhaps more leaders. The Hohokam culture spread widely, from near the Mexican border to the Verde River in the north. There seemed to be a group of elite people, and craftsmen gained more social importance. Platform mounds, similar to those in central Mexico, appeared. These might have been linked to the upper class or religious activities. Trade items from Mexico included copper bells, mosaics, stone mirrors, and colorful birds like macaws.

Classic Period (AD 1050/1150–1450)

This period was a time of big changes and growth. The important town of Snaketown was suddenly left empty. Parts of it seemed to have burned, and people never lived there again. During this time, large and impressive buildings were constructed in the Salt-Gila Basin. These included big, rectangular, adobe-walled compounds with platform mounds and great houses, like the one at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. At the same time, the Hohokam's influence in other regions became much smaller.

Soho Phase (AD 1050/1150–1300)

The main type of pottery for this phase was Casa Grande red-on-buff. This pottery was mostly jars with necks, decorated with simple geometric designs. It seems to have been made in several places in the Gila River basin. The Hohokam culture shrank its territory. There were two major reorganizations. The first happened around 1150 AD, with a slight increase in population and almost everyone adopting pitroom architecture. These early pitrooms were made of wood covered with thick adobe plaster. Homes were grouped around open courtyards, which were then grouped around a central area, often with small platform mounds. Larger villages became more crowded, while smaller settlements declined.

Civano Phase (AD 1300–1350/1375)

While Casa Grande red-on-buff pottery was still made, the main pottery of this phase was Salado polychrome, especially Gila polychrome. This pottery was either made locally or traded for. The comal (a flat griddle like those in Mexico) was introduced, and they made bird-shaped pots. Beautiful stone and shell jewelry, like nose plugs, pendants, and bracelets, show that jewelry making was at its best during this time. More red pottery was made, and almost everyone north of the Gila River started using inhumation (burying the dead) instead of cremation. These practices were similar to those of the historic O'odham people.

After 1300 AD, Hohokam villages changed their layout. They built large, rectangular outer walls that partly or fully enclosed courtyards and plazas. Each courtyard might have had one to four large, rectangular, adobe-walled pitrooms. These communities were groups of 5 to 25 adobe-walled compounds, often around a very large compound with a platform mound or great house. Great houses, like the one at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, were only built in the largest communities. These stone or adobe buildings could be up to four stories tall. They were likely used by leaders or religious figures and might have been built to align with stars. Trade with Mexico seemed to decrease, but more goods came from Pueblo people to the north and east.

Between 1350 and 1375 AD, the Hohokam culture became weaker. Many of the largest settlements were abandoned. Changes in climate likely affected Hohokam farming. Floods in the mid-14th century made the Salt River bed much deeper and destroyed canal entrances. This made hundreds of miles of canals useless. Even though the Gila River canals were less affected, they were also abandoned. The Hohokam split into smaller groups, and the population decreased slightly. This decline was not as severe as once thought, as smaller groups are harder to find. Animal populations stayed the same, suggesting the human population was still present, just in smaller, harder-to-find groups.

Polvoron Phase (AD 1350/1375–1450)

This phase is known for the widespread use of Salado polychrome pottery. After 1375 AD, the Hohokam left most villages and canal systems in the lower Salt River basin. The area was still lived in, but by far fewer people. The remaining villages were very small and mostly along the Gila River. This period marks the end of the Hohokam culture and the beginning of the modern O'odham people.

Ceramic Tradition

The first settled farming communities in central Arizona appeared between 1000 and 500 BCE. However, the first pottery only shows up just before the Hohokam culture began around 300 CE.

Some archaeologists think the sudden appearance of pottery means new people moved into the Phoenix area, leading to the rise of the Hohokam. Others believe that many Hohokam cultural traits were already present in the local farming communities. This is why pottery helps fuel the debate about where the Hohokam came from.

It was once thought that Hohokam pottery materials varied by location, using local resources. However, recent studies show that pottery was made in many different places and then traded. Several stone palettes, from different periods, were found in the Gila Bend Region. This suggests the Hohokam stayed in one area for a long time.

Hohokam pottery is known for its distinct Plain, Red, and Decorated buffware. It was made using a technique called coiling. A small clay base was connected to a series of coils. These coils were then thinned and shaped using a paddle and anvil. Hohokam Plain and Red pottery often contained materials like mica, schist, granite, or quartz. These materials help archaeologists identify where the pottery was made, such as Gila (Gila River basin) or Salt (Salt or Verde River basins).

Plain pottery surfaces were smoothed, and many were polished or slipped with other minerals. After firing, they turned light or dark brown, gray, or orange. Later, the inside of bowls was coated with a black material. Hohokam Red pottery was coated with an iron-based pigment that turned red after firing. Decorated Hohokam pottery was made similarly but used finer clays and small amounts of finely ground mica and plant material.

Cultural Divisions

Archaeologists use names like Hohokam, Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi), Mogollon, or Patayan to describe differences among ancient peoples. These names and divisions were created by people who lived much later than these cultures. They are based only on the information available at the time. They can change as new discoveries are made or as scientists' views change. An archaeological division does not necessarily mean a specific language group or a political group like a "tribe."

When we use these modern cultural divisions in the Southwest, we should remember three things:

- Archaeologists study physical remains, like pottery pieces, human bones, stone tools, or old buildings. But many other parts of ancient cultures, like their Languages, beliefs, and behaviors, are hard to understand from physical objects alone. Cultural divisions are tools for modern scientists. They might not be how ancient people saw themselves. Modern cultures in this region, many of whom are descendants of these ancient people, have a wide range of lifestyles, languages, and beliefs. This suggests ancient people were also more diverse than their remains might show.

- The idea of "style" helps us understand things like pottery or buildings. Within a group, different ways of doing the same thing can be adopted by smaller parts of the group. For example, different styles of clothing might be popular with older versus younger generations. Some cultural differences might come from traditions passed down through generations. Style differences might also show social status, gender, clan membership, religious beliefs, or alliances. Sometimes, differences just reflect the different resources available in a certain place or time.

- Naming culture groups, like the Hohokam, can make it seem like their territories had clear borders, like modern countries. But this was not the case. Ancient people often traded, worshipped, and worked with other nearby groups. Cultural differences usually changed gradually as the distance between groups increased. Sometimes, social or political situations, or natural barriers like mountains, rivers, or the Grand Canyon, could reduce contact between groups. Today, experts believe that the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo cultures were more similar to each other and more different from the Hohokam because of the geography and different climate zones in the Southwest.

Major Core Area Villages and Cities

The true understanding of the Hohokam comes from looking at all their material culture. This is best seen by studying their main population centers, which were large villages or even cities. While they shared a common culture, each of these major places had its own unique story of how it started, grew, and was eventually abandoned. Below are short descriptions of the largest and most important ancient villages, towns, and cities in the Hohokam core area.

Snaketown

Snaketown was the most important settlement during the Preclassic period and the main community in the Hohokam culture. Today, Snaketown is part of the Hohokam Pima National Monument, near Santan, Arizona. This monument was created by Congress in 1972. Digs in the 1930s and 1960s showed that people lived there from about 300 BC to 1050 AD. At its peak in the early 11th century, Snaketown was the center of Hohokam culture and where their special buffware pottery was made. After the last digs by Emil Haury, the site was completely covered with earth, so nothing is visible above ground today.

Snaketown had two ball courts, many trash mounds, a small ceremonial mound, a large central plaza, several big community houses, and hundreds of residential pithouses. It might have been home to thousands of people. After Snaketown was abandoned, some smaller settlements were founded nearby and were lived in until the early 14th century AD. The Hohokam Pima National Monument is on Gila River Indian Community land and is owned by the tribe. It covers almost 7 square kilometers (1,700 acres). The tribe has decided not to open this very sensitive ancient site to the public.

Grewe-Casa Grande

The larger Grewe-Casa Grande Site was the biggest Hohokam community in the middle Gila River valley. It was located between two main canals. Over time, this community was recorded as several separate archaeological sites, including Casa Grande, Grewe, Vahki Inn Village, and Horvath sites. These sites were lived in during the Preclassic and Classic periods. Each had between two and 20 large living areas. The entire Grewe-Casa Grande archaeological site covered about 3.6 square kilometers (900 acres), centered near the modern city of Coolidge, Arizona.

Most people are drawn to the four-story great house at the center of the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. Stories from the Akimel O'odham people say that a powerful chief named Sial Teu-utak Sivan (meaning "Turquoise Leader") built this huge structure. In the ancient Hohokam language, the great house and nearby ruins were called Sivan Vah'Ki, meaning "Abandoned House" or "Village of the chief." When Eusebio Francesco Chini (Father Kino) arrived in 1694, the great house was already abandoned and falling apart. Despite this, later missionaries used it to hold Mass.

Adolph Francis Alphonse Bandelier made one of the first detailed maps of the Casa Grande site in 1884. Jesse Walter Fewkes and Cosmos Mindeleff also described the area. Between 1906 and 1912, Fewkes dug and stabilized parts of the site. In 1927, Harold Gladwin dug test pits at the Grewe and Casa Grande sites. He also dug parts of an adobe-walled compound. Large-scale excavations were done in 1930 and 1931. This project focused on a 12-hectare (30-acre) area at the Grewe site and Compound F within the Casa Grande National Monument. They found 172 burials, hundreds of thousands of artifacts, about 60 pithouses, and a ballcourt.

More digs were done in 1933 and 1934. These showed that large late Preclassic and early Classic period settlements were in the monument area. The biggest archaeological project was from 1995 to 1997, covering 5.3 hectares (13 acres) across parts of the Casa Grande, Grewe, and Horvath sites. This project found or dug 247 pithouses, 24 pitrooms, 11 canal alignments, a ballcourt, and parts of four adobe-walled compounds. They also found 158 burials and over 400,000 artifacts.

Based on these projects, we can understand the history of the Grewe-Casa Grande site better. This important village seems to have started around the sixth century AD with groups of pithouses around small, round plazas. By the eighth century AD, it had grown into a full summer home for priests and chiefs. It had densely packed pithouses around small courtyards, which formed a large central plaza. Next to the plaza was a medium-sized ballcourt.

In the 10th century, at least two large secondary villages and about a dozen new small settlements were founded to the west. When Snaketown was abandoned and the Classic period began, Grewe-Casa Grande became one of the largest and most important Hohokam centers. At its peak, it had about 100 trash mounds, hundreds of pithouses, and four or five ballcourts. However, it never reached the same status as Snaketown. As the western part of the settlement grew, large parts of the eastern half declined. By 1300 AD, the village had about 19 adobe-walled residential compounds, pitroom clusters, a platform mound, a great house, and many trash mounds. After the mid-14th century, it began to decline quickly. Around 1400 or 1450 AD, the entire settlement was abandoned, except for a small occupation during the Polvoron phase.

Today, about 60% of the Grewe-Casa Grande site has been destroyed by farming and building, or has been excavated. About 40% of this huge settlement is now within the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. This was the nation's first archaeological reserve in 1892 and became a national monument in 1918. Visitors can see an interpretive center, walk among the ruins of Compound A, and view the great house, which has been protected by a modern-looking roof since 1932.

Pueblo Grande

Pueblo Grande Museum Archeological Park near central Phoenix has preserved ruins and artifact exhibits. Archaeological finds have also been recorded along the nearby light-rail construction.

Mesa Grande

The Mesa Grande ruin in Mesa, Arizona, is another large Hohokam village. It was lived in during both the Preclassic and Classic periods, from about 200 to 1450 AD. Although this settlement seems to have been very important, not much archaeological work has been done there, except for mapping and stabilization by the Southwest Archaeology Team (SWAT). SWAT's volunteer work at Mesa Grande began in the mid-1990s and continues today.

At its peak, this settlement might have had as many as 20 separate living areas and covered hundreds of acres. Today, due to city development, only a 2.6-hectare (6.4-acre) piece of the village remains. This plot contains the ruins of a large adobe compound and a 9-meter (27-foot) high, mostly intact, platform mound. This is one of only three Hohokam platform mounds left in the greater Phoenix area. This land became public property in the mid-1980s, so the compound and mound were saved. There is a visitor center at the site, open from October to May each year.

Las Colinas and Los Hornos

The Hohokam settlement of Los Hornos (Spanish for 'the ovens') is in modern-day Tempe, Arizona. Frank Cushing first investigated it in 1887. With city growth, more digs were done in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. These projects showed a large village from both the Preclassic and Classic periods. It was organized similarly to Snaketown and Pueblo Grande, but on a slightly smaller scale. Los Hornos seems to have started around 400 AD as a small group of rectangular pithouses.

Over time, Los Hornos grew along a series of large canals to the east and southeast. At the peak of the Preclassic period, this settlement had one large ball court, a big central plaza, several cremation cemeteries, many trash mounds, and hundreds of pithouses. Detailed digs of 50 Preclassic pithouses provided valuable information about homes and how space was used inside.

After a short period of population decline and changes in the late 11th and early 12th centuries AD, Los Hornos continued to shift east and south in the Classic period. This large village seems to have recovered and became important again in the late Soho or early Civano phases, from 1277 to 1325 AD. At this time, Los Hornos had about 15 residential compounds, a large central plaza, a big rectangular platform mound, several large trash mounds, and many pits and cemeteries.

Before the mid-14th century AD, with the rise of Los Muertos a few miles southeast, the Los Hornos community began to decline quickly. Although much smaller, the city was still lived in until it was mostly abandoned between 1400 and 1450 AD, like much of the Lower Salt River basin. Today, most of the Los Hornos village has been destroyed by modern roads, homes, and businesses, or has been excavated. The only visible remains of this once important Hohokam city are some low trash mounds in the Old Guadalupe Village Cemetery.

Archaeological sites

The following Hohokam archaeological sites and museums are open to the public, except for Hohokam Pima National Monument.

- Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Coolidge, Arizona. Casa Grande Ruins National Monument

- Hohokam Pima National Monument (Snaketown), Gila River Indian Reservation (closed to public).

- Indian Mesa, Peoria, Arizona

- Mesa Grande Ruins, Mesa, Arizona.

- Painted Rock Petroglyph Site, Theba, Arizona

- Park of the Canals, Mesa, Arizona.

- Pueblo Grande Museum Archeological Park, Phoenix, Arizona.

- Sears-Kay Ruin – Hohokam Fort on top of a foothill in Carefree, Arizona.

- White Tank Mountain Regional Park, White Tank Mountains

Gallery

- Images related to Hohokam culture

-

Hohokam corner-notched arrowhead in situ in the Tucson Basin

-

Pictographs at Huerfano Butte.

-

Hohokam Glycymeris shell art.

See also

In Spanish: Hohokam para niños

In Spanish: Hohokam para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |