Woodblock printing facts for kids

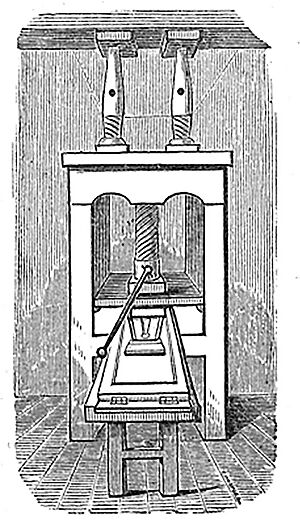

Woodblock printing is a cool way to print text, pictures, or patterns. It was used a lot in East Asia, especially in China, where it started a long, long time ago. At first, people used it to print on cloth, and later on paper. To make a print, artists carve a wooden block. They leave only the parts they want to print raised. Then, they put ink on these raised parts and press them onto paper or cloth. This is called relief printing. Carving the blocks takes a lot of skill and hard work, but once a block is ready, you can print many copies!

The oldest examples of woodblock printing on cloth come from China, dating back to before 220 AD. By the 7th century AD, woodblock printing was common in Tang China. It stayed the main way to print books and pictures in East Asia until the 1800s. Ukiyo-e is a famous type of Japanese woodblock art print. In Europe, this method was mostly used for printing images on paper, and it's called woodcut.

History of Woodblock Printing

How Printing Began in China

People believe that printing might have been inspired by carved seals made of metal or stone, and also by stone tablets with writing on them. In ancient China, copies of important texts were carved onto large stone tablets and put in public places. Students and scholars would then make copies by rubbing ink onto paper placed over the carvings. This method likely led to the idea of printing.

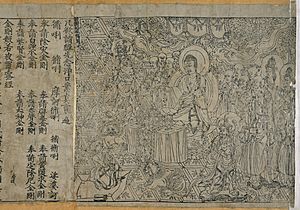

Mahayana Buddhism played a big role in the rise of printing. Buddhists believed that religious texts were very important and had special powers. Copying these texts was a way to gain good karma. So, Buddhists quickly saw how printing could help them make many copies of their texts. By the 7th century, they were using woodblocks to create special religious documents. The oldest known example is a small scroll with a Buddhist spell, found in a tomb in Xi'an. It was printed using woodblocks during the Tang dynasty, around 650–670 AD.

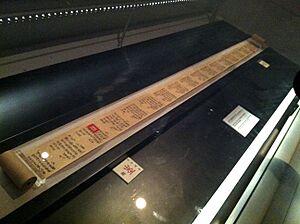

The oldest text with a specific printing date was found in the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang in 1907. It's a copy of the Diamond Sutra, which is 14 feet long! At the end, it says it was made by Wang Jie on May 11, AD 868. This makes it the world's oldest reliably dated woodblock scroll.

How Printing Spread Across Asia

Woodblock printing quickly appeared in Korea and Japan after China. In South Korea, The Great Dharani Sutra was found in 1966. It was printed between 704 and 751 AD. In Japan, Empress Shōtoku ordered one million copies of a Buddhist spell to be printed around 770 AD. Each copy was stored in a tiny wooden pagoda, and these are known as the Hyakumantō Darani.

By 1000 AD, woodblock printing had spread across Eurasia. It even reached the Byzantine Empire. However, printing on cloth only became common in Europe around 1300. The Chinese technique of block printing was brought to Europe in the 13th century, after paper became available there.

Printing in the Song Dynasty

During the Song dynasty (960-1279), printing really took off. From 932 to 955, important texts like the Thirteen Classics were printed. The government used block printing to share official versions of these books. Other printed works included histories, philosophy, encyclopedias, and books on medicine and war.

In 971, work began on a huge project: printing the complete Tripiṭaka Buddhist Canon in Chengdu. It took 10 years and 130,000 blocks to finish! This massive set of books was completed in 983.

Before printing, private book collections in China were growing. But after woodblock printing became common, official, business, and private printing houses appeared. The number and size of book collections grew super fast! Owning a library of 10,000 to 20,000 books became normal.

Woodblock printing also changed how books looked. Scrolls slowly changed into "concertina binding," which was like an accordion. This made it easier to find a specific page. Later, "butterfly binding" was invented, where two pages were printed on one sheet, then folded inwards and glued together. This created a book with alternating printed and blank pages. Eventually, sewn bindings became popular.

Printing in the Ming Dynasty

Even though woodblock printing was very productive, handwritten books were still common in China until the end of the empire. It was often cheaper to pay someone to copy a book by hand than to buy a printed one! Elite scholars sometimes even preferred handwritten books, thinking printed books were "for those who did not truly care about books."

However, the cost of books dropped by about 90 percent by the late 1500s because of printing. This meant more people could afford books, and more people learned to read. In 1488, a Korean visitor to China noticed that "even village children, ferrymen, and sailors" could read, especially in the south.

Colorful Prints

In more recent times, Chinese printing continued to use colors. Black-and-white woodcuts were replaced by colorful ones. This was done by printing the same image multiple times, each time with a different color ink.

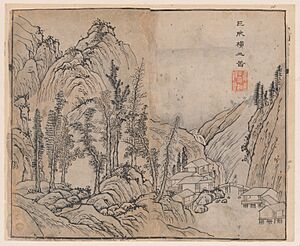

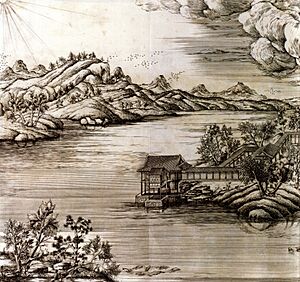

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, prints with three or even five colors appeared. The oldest surviving example is the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Paintings (1644) by Hu Zhengyan. It's still copied today and features landscapes, flowers, animals, and more. Another famous collection is the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, published between 1679 and 1701. It was known for its beautiful colors and drawings, which influenced Chinese painting for a long time.

Printing in Korea (Goryeo)

In 989, the Korean king Seongjong of Goryeo asked China for a copy of their complete Buddhist texts. In 1011, Korea started carving its own set, known as the Goryeo Daejanggyeong. This huge project was finished in 1087, with about 6,000 volumes. Sadly, the original wooden blocks were destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1232.

King Gojong ordered a new set to be made, and it was finished in just 12 years, in 1248. This new Goryeo Daejanggyeong has 81,258 printing blocks, over 52 million characters, and 6,568 volumes! Because it was so carefully made and has lasted over 760 years, it's considered the most accurate collection of Buddhist texts in Classical Chinese.

Printing in Japan

In Japan, during the Kamakura period (12th-13th centuries), many books were printed using woodblocks at Buddhist temples.

Mass production of woodblock prints really grew during the Edo period (1603-1868) because so many Japanese people could read. By 1800, almost all samurai could read, and about half of common people could too, thanks to private schools. There were over 600 book rental shops in Edo (now Tokyo)! People could borrow illustrated woodblock books on many topics, like travel guides, gardening, cooking, and funny stories. Famous bestsellers were reprinted many times.

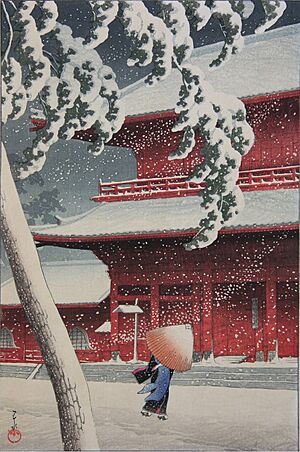

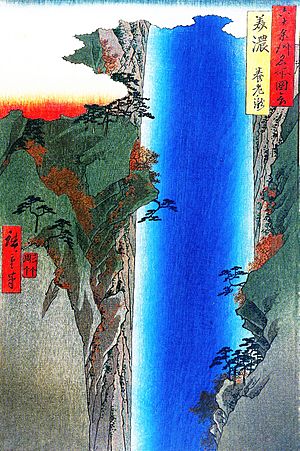

From the 1600s to the 1800s, ukiyo-e prints became very popular. These prints showed everyday life, kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, landscapes, and historical tales. Hokusai and Hiroshige are two of the most famous ukiyo-e artists. In the 1700s, Suzuki Harunobu created a technique for multicolor woodblock printing called nishiki-e, which greatly improved Japanese woodblock art. Ukiyo-e even influenced European art styles like Japonisme and Impressionism.

Printing in Europe

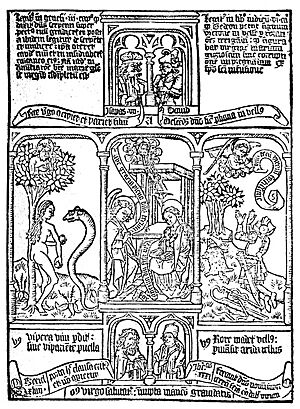

In Europe, "block books" appeared in the mid-1400s. In these books, both the text and pictures were carved onto a single block for each page. They were a cheaper option than handwritten books or books made with movable type. These block books were usually short, heavily illustrated works, like bestsellers of their time. They were also used a lot for printing playing cards.

Movable Type vs. Woodblock Printing

China

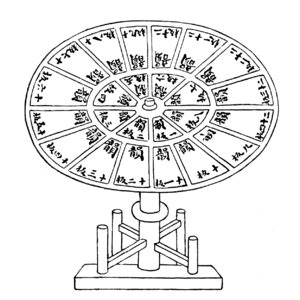

Movable type, where individual characters are used instead of whole blocks, was invented in China around 1041 by Bi Sheng. At first, it was made of ceramic and wood, and later metal. The oldest existing book printed with movable type is the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union, printed in Western Xia between 1139 and 1193.

However, movable type never fully replaced woodblock printing in East Asia. Even during the Ming and Qing dynasties, woodblock printing was still the main method. Only about 10% of printed materials used movable type, while 90% used the older woodblock method. Woodblocks remained the most common way to print in China until lithography (a different printing method) arrived in the late 1800s.

Some people used to think that woodblock printing held back printing in East Asia. But modern experts disagree. Early European visitors to China were surprised by how cheap and common printed books were there. For example, in the late 1800s, one British observer noted that books in China were incredibly cheap compared to his home country, even though each page required a block to be carved. This showed how widely woodblock printing was used.

Korea

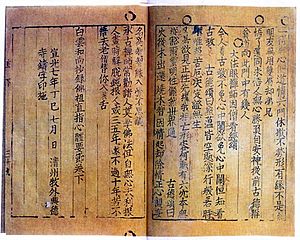

In 1234, metal movable type was used in Goryeo (Korea) to print a 50-volume book. However, no copies of that book exist today. The oldest existing book printed with movable metal type is the Jikji from 1377.

But just like in China, movable type never replaced woodblock printing in Korea. Even when the Korean alphabet, Hangeul, was created in the 1400s, it was first printed using woodblocks. Movable type was mostly used by the royal family and a small group of elite people.

Japan

Western-style movable type printing presses came to Japan in 1590. However, these presses were stopped after Christianity was banned in 1614. Movable type printing presses taken from Korea in 1593 were also used.

Tokugawa Ieyasu started a printing school in Kyoto in 1599, using Japanese wooden movable type. He oversaw the creation of 100,000 types, which were used to print many political and historical books.

Artists like Honami Kōetsu and Suminokura Soan used movable type to create beautiful art books. These books, known as Saga Books, were printed on expensive paper and had fancy decorations. They are considered the first and finest printed copies of many classic Japanese tales.

However, by 1640, craftsmen decided that the flowing, handwritten style of Japanese writing looked better when printed with woodblocks. So, woodblocks became the main printing method again for most of the Edo period. Movable type printing didn't become common again until the 1870s, during the Meiji period, when Japan started to modernize.

How Woodblock Printing Works

Jia xie is a special way to dye textiles (usually silk) using woodblocks, invented in China between the 5th and 6th centuries. Two blocks are made, one for the top and one for the bottom, with carved-out spaces. The cloth is folded and placed between the blocks. By opening different spaces and filling them with different colored dyes, a colorful pattern can be printed over a large area of folded cloth.

Printing with Colors

The earliest known woodblock printing was actually in color! Chinese silk from the Han dynasty was printed in three colors.

Using colors is very common in Asian woodblock printing on paper. In China, the first known example of color printing on paper is a Diamond Sutra from 1341, printed in black and red. The earliest dated book printed in more than two colors is Chengshi moyuan (1606), a book about ink-cakes. This technique became very advanced in art books published in the early 1600s. Famous examples include Hu Zhengyan's Treatise on the Paintings and Writings of the Ten Bamboo Studio (1633) and the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (1679 and 1701).

Images for kids

-

Bronze plate for printing an advertisement for the Liu family needle shop at Jinan, Song dynasty (960-1279). This is the world's oldest existing print advertisement!

See also

In Spanish: Xilografía para niños

In Spanish: Xilografía para niños

- Ajrak

- Woodcut

- Banhua

- Old master print

- New Year picture

- Kalamkari

- Ghalamkar

- Bagh Print

- Textile printing

- Bagru Print

- Conservation and restoration of woodblock prints

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |