Mogao Caves facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mogao Caves |

|

|---|---|

| Native name 莫高窟 | |

|

|

| Location | Dunhuang, Gansu, China |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 440 |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Mogao Caves | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Mogao Caves" in Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 莫高窟 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

The Mogao Caves are a huge system of 500 temples carved into cliffs. They are also known as the Thousand Buddha Grottoes. These caves are about 25 kilometers (15 miles) southeast of Dunhuang, an oasis city in Gansu province, China. Dunhuang was an important stop on the ancient Silk Road, a famous trade route.

The Mogao Caves hold some of the best examples of Buddhist art from a period of 1,000 years. The first caves were dug in 366 AD for Buddhist monks to meditate and worship. Over time, the site became a popular place for pilgrims. New caves were built there until the 14th century. The Mogao Caves are among the most famous ancient Buddhist sites in China, along with the Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Grottoes.

In 1900, a huge collection of old documents was found in a secret room called the "Library Cave." This cave had been sealed up in the 11th century. The documents from this library are now spread across the world. The largest collections are in Beijing, London, Paris, and Berlin. The International Dunhuang Project helps scholars study these important writings. Today, the Mogao Caves are a popular tourist spot, but the number of visitors is limited to help protect the ancient art.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The caves are often called the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas (Chinese: 千佛洞; pinyin: qiānfó dòng) in Chinese. Some people think this name came from a story about a monk named Yuezun. He supposedly saw a vision of a thousand Buddhas at the site. Another idea is that the name comes from the many small Buddha figures painted on the cave walls.

The name Mogao Caves (Chinese: 莫高窟; pinyin: Mògāo kū) was used during the Tang dynasty. 'Mogao' might mean "peerless" or "none higher." It could also mean "high in the desert." The nearby city of Dunhuang means "blazing beacon." This name came from the beacons used to warn of attacks at this frontier outpost.

A Long History of Art

Dunhuang was first set up as a military outpost by the Han Dynasty Emperor Wudi in 111 BC. It protected China from northern tribes. It also became a key gateway to the West and a busy trade center on the Silk Road. Many different people and religions, like Buddhism, met here.

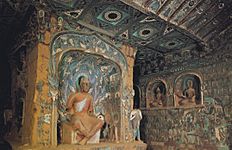

The Mogao Caves began to be built in the 4th century AD. They were used as a place for Buddhist worship and spiritual journeys. The caves contain over 400,000 square feet of beautiful paintings and sculptures. This makes them one of the largest collections of Buddhist art in the world.

A Buddhist monk named Lè Zūn (also called Yuezun) is said to have started the caves in 366 AD. He had a vision of a thousand Buddhas glowing with golden light. This inspired him to create the first cave. Another monk, Faliang, joined him later. The site slowly grew, and by the time of the Northern Liang period, a small group of monks lived there. At first, the caves were just for monks to meditate. But they soon grew to serve the monasteries that appeared nearby.

The oldest decorated Mogao Caves (like 268, 272, and 275) were made between 419 and 439 CE. They look similar to some of the Kizil Caves. Ruling families from the Northern Wei and Northern Zhou dynasties then built many more caves. The site truly thrived during the short-lived Sui Dynasty. By the Tang Dynasty, there were over a thousand caves.

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, the Mogao Caves became a public place of worship and pilgrimage. From the 4th to the 14th century, monks built caves with money from donors. These caves were painted with great detail. The paintings and architecture helped people meditate. They also showed what the path to enlightenment looked like. They helped people remember Buddhist stories and taught those who couldn't read about Buddhist beliefs. Important people like clergy, local leaders, foreign visitors, and even Chinese emperors sponsored the main caves. Other caves might have been paid for by merchants, soldiers, and local groups, including women's groups.

During the Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang was a major trade hub on the Silk Road and a big religious center. Many caves were built at Mogao during this time. This includes the two giant Buddha statues. The largest one was built in 695 AD, after Empress Wu Zetian ordered giant statues to be built across the country. The site was not harmed during the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution in 845. This was because Dunhuang was under Tibetan control at the time.

After the Tang Dynasty, the site slowly declined. No new caves were built after the Yuan Dynasty. By then, Islam had spread across Central Asia. The Silk Road became less important as trade shifted to sea routes. During the Ming Dynasty, the Silk Road was officially closed. Dunhuang became less populated and forgotten by the outside world. Most of the Mogao caves were left empty. However, the site was still used by local people for worship and pilgrimage in the early 1900s.

Rediscovering the Caves

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Western explorers became interested in the ancient Silk Road. They found lost cities in Central Asia. Those who passed through Dunhuang noticed the amazing murals, sculptures, and artifacts at Mogao. There are about half a million square feet of religious wall paintings inside the caves.

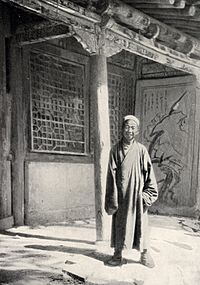

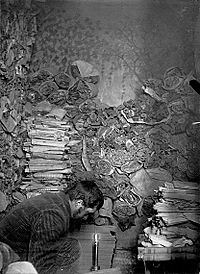

The biggest discovery was made by a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu. He had made himself the guardian of some of these temples. He was trying to raise money to fix the statues. Some caves were blocked by sand. Wang worked to clear the sand and restore the site. On June 25, 1900, he found a walled-up area behind a corridor in one cave. Behind the wall was a small cave filled with a huge collection of old writings.

News of Wang's discovery reached a British/Indian group led by archaeologist Aurel Stein in 1907. Stein made a deal with Wang. He gave Wang money for his restoration efforts in exchange for many manuscripts, paintings, and textiles. After Stein, a French expedition led by Paul Pelliot acquired thousands of items in 1908. Then came a Japanese expedition in 1911 and a Russian one in 1914.

Scholars in Beijing realized how valuable these documents were. They worried that the remaining manuscripts might be lost. In 1910, they convinced the government to bring the rest of the manuscripts to Beijing. However, not all of them made it, and some were stolen. In 1921, some caves were damaged by White Russian soldiers who were housed there. In 1924, American explorer Langdon Warner took some murals and a statue from the caves.

The situation improved in 1941. A painter named Zhang Daqian arrived at the caves with a team. He spent two and a half years repairing and copying the murals. His work helped make the art of Dunhuang famous in China. In 1944, the Research Institute of Dunhuang Art (now the Dunhuang Research Academy) was set up to protect the site. In 1956, Zhou Enlai, China's first Premier, took a personal interest. He approved money to repair and protect the site. In 1961, the Mogao Caves were declared a protected historical monument. Large-scale restoration work began soon after. The site was saved from damage during the Cultural Revolution.

Today, efforts continue to preserve and study the site. The Mogao Caves became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. More caves were found between 1988 and 1995. The Dunhuang Academy is also working on "digital conservation." They are taking photos and creating 3D models of the caves. This allows people to explore the caves virtually.

The Library Cave

Cave 17, found by Wang Yuanlu, is known as the Library Cave. It is located near the entrance to Cave 16. It was first used as a memorial for a monk named Hongbian, who died in 862. Hongbian was responsible for building Cave 16. The Library Cave might have been his private retreat. It originally held his statue, which was moved when the cave was used to store manuscripts.

A huge number of documents were found in the cave. They dated from 406 to 1002 AD. There were about 1,100 bundles of scrolls and over 15,000 paper books and shorter texts. These included a Hebrew prayer. It's thought that 50,000 ancient documents were found. They covered topics like literature, philosophy, art, and medicine. The Library Cave also contained textiles, banners, broken Buddha figures, and other Buddhist items.

The Library Cave was sealed off in the early 11th century. People have different ideas why. Some think it was a storage place for old or damaged manuscripts. It might have been sealed when the area was threatened. Another idea is that the cave was simply a book storage room that became full.

Others believe the monks quickly hid the documents before an attack. This might have happened when the Western Xia invaded in 1035. Another theory is that the items were hidden from Muslims moving eastward. Monks might have heard about the fall of the Buddhist kingdom of Khotan in 1006. They then sealed their library to protect it. The latest date found on a document in the cave is 1002. So, the cave was likely sealed not long after that.

The Dunhuang Manuscripts

The manuscripts from the Library Cave date from the 5th century to the early 11th century. Up to 50,000 manuscripts may have been stored there. Most are in Chinese, but many are in other languages like Tibetan, Uighur, Sanskrit, and Sogdian. They include old paper scrolls, Tibetan books, and paintings on hemp, silk, or paper. Most of the scrolls are about Buddhism. However, they also cover many other topics. These include original commentaries, prayer books, Confucian works, Taoist works, and even Christian works. There are also government documents, dictionaries, and calligraphy exercises.

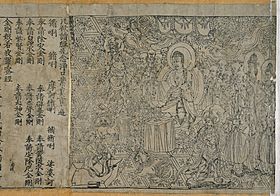

Many of these manuscripts were unknown or thought to be lost before their discovery. They offer a special look into religious and daily life in Northern China and Central Asia. The Library Cave manuscripts include the oldest known dated printed book, the Diamond Sutra from 868 AD. They also include Christian documents, a Go manual, and ancient music scores. These scrolls show how Buddhism developed in China. They also record the political and cultural life of the time. They even give a rare glimpse into the lives of ordinary people.

The manuscripts were spread around the world after they were found. Stein's collection was divided between Britain and India. He chose about 7,000 complete manuscripts and 6,000 fragments. Pelliot took almost 10,000 documents. Unlike Stein, Pelliot understood Chinese. This allowed him to choose a better selection of documents. He was interested in unusual manuscripts, like those about the monastery's management. Many of these survived because they were reused, with Buddhist texts written on the back of other papers. Wang sold hundreds more manuscripts to Otani Kozui and Sergei Oldenburg. Now, efforts are being made to put the Library Cave manuscripts online. They are available through the International Dunhuang Project.

The Art of Mogao Caves

The art at Dunhuang includes more than ten main types. These are architecture, sculpture, wall paintings, silk paintings, calligraphy, woodblock printing, embroidery, literature, music, dance, and popular entertainment.

Cave Architecture

The caves are carved into the cliff. But the local rock is soft gravel. This means it's not good for detailed sculptures or fancy building parts. Many early caves were inspired by Indian Buddhist rock-cut temples, like the Ajanta Caves. They had a central column with sculptures. Worshippers could walk around it to gain blessings. Other caves are like traditional Chinese and Buddhist temples. They might have a pyramid-shaped ceiling painted to look like a tent. Some caves for meditation are based on Indian monastery plans. They have small side rooms just big enough for one person.

Many caves originally had wooden porches or temples built out from the cliff. Most of these have disappeared. Only five remain. The two oldest are rare examples of wooden architecture from the Song dynasty. The most famous wooden building at the site houses the Great Buddha. It was first built during the Tang dynasty. It was originally four stories high. It has been repaired many times and is now a 9-story building.

Amazing Murals

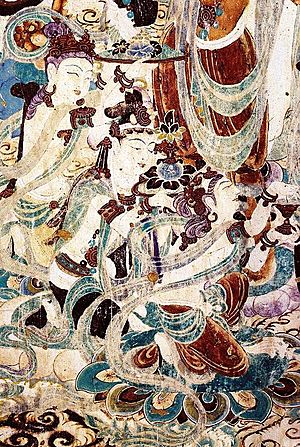

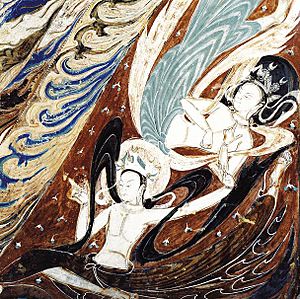

The murals in the caves span over a thousand years, from the 5th to the 14th century. Many older ones were repainted later. The murals cover a huge area of about 490,000 square feet. The most fully painted caves have art all over the walls and ceilings. Spaces not taken by figures are filled with geometric or plant designs. The sculptures are also brightly painted. These murals are valued for their size, rich content, and artistic skill. Buddhist subjects are most common. However, some show traditional mythical scenes and portraits of the people who paid for them. These murals show how Buddhist art changed in China for nearly a thousand years. The art was best during the Tang period. Its quality went down after the 10th century.

Early murals show strong Indian and Central Asian influences. This can be seen in the painting techniques, composition, and even the clothes worn by the figures. But a unique Dunhuang style started to appear during the Northern Wei Dynasty. Chinese, Central Asian, and Indian designs can be found in a single cave. Chinese elements became more common during the Western Wei period.

Many caves feature rows of small seated Buddha figures. This is why some are called "Thousand Buddhas Caves." These small Buddhas were made using stencils to create identical figures. Flying apsaras, or heavenly beings, might be painted on the ceiling. Figures of donors might be shown along the bottom of the walls. The paintings often show jataka tales, which are stories about Buddha's life. They also depict avadana, which are parables about karma. The murals can also show other religious themes.

Bodhisattvas started appearing during the Northern Zhou period. Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), who was originally male but later became female, was the most popular. Most caves show influences from both Mahayana and Sravakayana Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism became the main form during the Sui Dynasty. A new idea in the Sui-Tang period was the visual representation of sutras. These were Mahayana Buddhist teachings turned into large, detailed narrative paintings. A key feature of Tang art in Mogao is the depiction of the paradise of the Pure Land. This shows how popular this type of Buddhism was during the Tang era. Art from Tantric Buddhism, like the eleven-headed Avalokitesvara, also started to appear in Mogao wall paintings during the Tang period. It became popular during the Tibetan occupation of Dunhuang and later, especially during the Yuan dynasty.

Many figures have darkened because the lead-based paints reacted with air and light. Many early murals in Dunhuang also used Indian painting techniques. These techniques used shading to create a 3D effect. However, the shading paint darkened over time. This resulted in heavy outlines that the artists did not intend. This shading technique was unique to Dunhuang in East Asia at this time. Such shading on human faces was not common in Chinese paintings until much later. Many murals have been repaired or repainted over the centuries. Older murals can be seen where later paintings have been removed.

Sculptures in Clay

There are about 2,400 clay sculptures left at Mogao. They were first built on a wooden frame, then covered with reeds. After that, they were shaped with clay stucco and painted. The giant statues, however, have a stone core. The Buddha is usually the main statue. He is often surrounded by boddhisattvas, heavenly kings, devas, and apsaras. There are also yaksas and other mythical creatures.

The early figures are simple. They are mainly Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Northern Wei Buddhas might have two Bodhisattva attendants. Two more disciples were added in Northern Zhou, making a group of five. Figures from the Sui and Tang periods might be in larger groups of seven or nine. Some show a large parinirvana scene with groups of mourners. Early sculptures were based on Indian and Central Asian styles. Some were in the Greco-Indian style of Gandhara. Over time, the sculptures looked more Chinese.

The two giant statues represent Maitreya Buddha. The older and larger one in Cave 96 is 35.5 meters (116 feet) high. It was built in 695 AD under orders from Empress Wu Zetian. The smaller one is 27 meters (89 feet) tall and was built between 713 and 741 AD. The larger northern giant Buddha was damaged in an earthquake. It has been repaired many times. Because of this, its clothing, color, and gestures have changed. Only its head still looks like it did in the Early Tang period. The southern statue is mostly in its original form, except for its right hand. The larger Buddha is housed in a famous 9-story wooden building.

One type of cave built during the Tibetan era is the Nirvana Cave. It features a large reclining Buddha that fills the entire length of the hall. Figures of mourners are also shown in murals or as sculptures behind the Buddha. The Buddha figure in Cave 158 is 15.6 meters (51 feet) long.

The "Library Cave" was originally a shrine for Hong Bian, a monk from the 9th century. His portrait statue was moved when the cave was sealed. It has now been returned. There is also a stone tablet describing his life. The wall behind the statue is painted with attendant figures. This mix of painted sculpture and wall paintings is very common at the site.

Paintings on Silk and Paper

Before the Library Cave was found, original paintings on silk and paper from the Tang dynasty were very rare. Most existing examples were copies made later. Over a thousand paintings on silk, banners, and embroideries were found in the Library Cave. None seem to be older than the late 7th century. Most of the paintings are by unknown artists, but many are of high quality, especially from the Tang period. Most are sutra paintings, images of Buddha, and narrative paintings. The paintings show some of the Chinese style from the capital Chang'an. But many also show Indian, Tibetan, and Uighur painting styles.

There are brush paintings in ink only, some in just two colors, and many in full color. Most common are single figures. Most paintings were probably given by an individual, who is often shown very small. The donor figures become much more detailed in their clothing by the 10th century.

Printed Images

The Library Cave is also important for rare early images and texts made by woodblock printing. This includes the famous Diamond Sutra, the oldest printed book that still exists. Other printed images were made to be hung. They often had text below with prayers and sometimes a dedication from the person who paid for them. Many images have color added by hand to the printed outline. Several sheets have repeated prints of the same Buddha image. These might have been stock for sale to pilgrims. But inscriptions show they were also printed at different times by individuals as a way to gain merit.

Ancient Textiles

The textiles found in the Library Cave include silk banners, altar hangings, manuscript wrappings, and monks' clothing (kāṣāya). Monks often wore clothes made from patches of different fabrics as a sign of humility. These textiles offer valuable information about the types of silk cloth and embroidery available at the time. Silk banners were used to decorate the cliff face at the caves during festivals. These are painted and sometimes embroidered. Valances used to decorate altars and temples had a horizontal strip at the top. From this hung streamers made from different cloths, ending in a V-shape.

Exploring the Caves

The caves were carved into the side of a cliff that is almost two kilometers (1.2 miles) long. At its peak, during the Tang Dynasty, there were over a thousand caves. But over time, many were lost, including the very first ones. Today, 735 caves exist at Mogao. The most famous ones are the 487 caves in the southern part of the cliff. These were used for pilgrimage and worship. Another 248 caves have been found to the north. These were living quarters, meditation rooms, and burial sites for monks. The southern caves are decorated, while the northern ones are mostly plain.

The caves are grouped by the time period they were built. New caves from a new dynasty were often made in different parts of the cliff. By studying the murals, sculptures, and other items, the dates of about five hundred caves have been figured out. Here is a list of caves by era:

- Sixteen Kingdoms (366–439 AD) - 7 caves, the oldest from the Northern Liang period.

- Northern Wei (439–534 AD) and Western Wei (535-556 AD) - 10 from each period.

- Northern Zhou (557–580 AD) - 15 caves.

- Sui Dynasty (581–618 AD) - 70 caves.

- Early Tang (618–704 AD) - 44 caves.

- High Tang (705–780 AD) - 80 caves.

- Middle Tang (781–847 AD) - 44 caves (Dunhuang was under Tibetan control during this time).

- Guiyijun period (848–1036 AD) - Dunhuang was ruled by the Zhang and Cao families.

- Late Tang (848–906 AD) - 60 caves.

- The Five Dynasties (907–960 AD) - 32 caves.

- Song Dynasty (960–1035 AD) - 43 caves.

- Western Xia (1036–1226 AD) - 82 caves.

- Yuan Dynasty (1227–1368 AD) - 10 caves.

Gallery

-

A full view of Zhang Qian's journey to the West, around 700 AD.

-

Details of the mural showing Zhang Qian's journey to the West. From Cave 323, 618–712 AD.

-

A Tang Chinese silk painting showing a young Sakyamuni cutting his hair.

-

Young female Buddhist donors. From Cave 98, Five Dynasties era.

-

A fresco showing the style of architecture from the Tang dynasty.

-

A fresco showing Tang style architecture in the Buddhist land.

-

Sogdian Daēnās showing two Zoroastrian deities once worshipped by the Sogdians.

See also

In Spanish: Cuevas de Mogao para niños

In Spanish: Cuevas de Mogao para niños

- List of World Heritage Sites in China

- Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

- Buddhism in China

- International Dunhuang Project

- Kizil Caves

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism