Sogdia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sogdia, Sogdiana

*S{əγ}ʷδīkᵊstən (𐼼𐼲𐼴𐼹𐼷𐼸𐼼𐽂𐼻 sγwδykstn), *S{əγ}ʷδū (𐼼𐼲𐼴𐼹𐼴 sγwδu)

|

|

|---|---|

| 6th century BC to 11th century AD | |

|

|

| Capital | Samarkand, Bukhara, Khujand, Kesh |

| Languages | Sogdian language |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Buddhism, Islam, Nestorian Christianity |

| Currency | Imitations of Sassanian coins and Chinese cash coins as well as "hybrids" of both. |

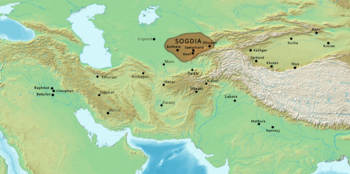

Sogdia, also known as Sogdiana, was an ancient civilization in Central Asia. It was located between two major rivers, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. Today, this area is part of countries like Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Sogdia was once a province of the powerful Achaemenid Empire. Its name is even mentioned on the famous Behistun Inscription by Darius the Great. Over many centuries, Sogdia was ruled by different empires. These included the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great, the Seleucid Empire, the Kushan Empire, and later, various Turkic and Muslim empires.

The cities of Sogdia, like Samarkand, were never fully united under one government. However, they were important centers. The Sogdian language, an ancient Iranian language, is no longer spoken. But a related language, Yaghnobi, is still used by some people in Tajikistan. Sogdian was once a very important language for trade and official documents in Central Asia.

Sogdian merchants were famous for their travels. They went as far as Imperial China and the Byzantine Empire. They played a key role in trade along the Silk Road. Over time, many Sogdians, who originally followed religions like Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and Buddhism, gradually became Muslims. This change happened after the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana in the 8th century.

Contents

- Where was Sogdia located?

- What does the name "Sogdia" mean?

- A brief history of Sogdia

- Sogdia under the Achaemenid Empire (546–327 BC)

- Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Period (327–145 BC)

- Saka and Kushan Periods (146 BC–260 AD)

- Sasanian Rule (260–479 AD)

- Hephthalite Control (479–557 AD)

- Turkic Khaganates (557–742 AD)

- Arab Muslim Conquest (8th century AD)

- Turco-Mongol Conquests: Kara-Khanid Khanate (999–1212)

- Sogdian economy and diplomacy

- Sogdian language and culture

- Sogdian communities and notable people

- See also

Where was Sogdia located?

Sogdia was north of Bactria and east of Khwarezm. It was situated between the Amu Darya (Oxus River) and the Syr Darya (Jaxartes River). This area included the fertile valley of the Zeravshan River. Today, Sogdian territory covers parts of the Samarkand Region and Bukhara Region in Uzbekistan. It also includes the Sughd region of Tajikistan. In ancient times, Sogdian cities even stretched towards Issyk Kul, like the site of Suyab.

What does the name "Sogdia" mean?

The name "Sogdia" comes from ancient words. Experts believe it is linked to a very old Indo-European word meaning "propel" or "shoot." This suggests that the name might have meant "archer." The ancient Persian inscriptions called the region "Sugda" or "Suguda." Over time, these names changed to "Sogdiana" in Greek.

A brief history of Sogdia

Right: 12-petalled flower from the cult structure in Sarazm, Sogdia, early 3rd millennium BC

Sogdia has a very long history, going back to the Bronze Age. Early towns appeared around the 4th millennium BC in places like Sarazm, Tajikistan. Later, people who spoke Eastern Iranian languages, like the Sogdians, settled in the area.

Sogdia under the Achaemenid Empire (546–327 BC)

Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, conquered Sogdia between 546 and 539 BC. This event was recorded by the Greek historian Herodotus. Darius I introduced the Aramaic alphabet and coins to Central Asia. Sogdians also became soldiers and cavalrymen in the Persian army. Some Sogdian soldiers even fought in the army of Xerxes I during his invasion of Greece in 480 BC.

Sogdia was likely governed from the nearby region of Bactria. It remained under Persian control until about 400 BC. After this, Sogdia became independent for a while. However, it was later conquered by Alexander the Great.

During this time, Sogdians were known for their trade. They offered valuable gifts like lapis lazuli and carnelian to the Persian kings. Even though they were sometimes independent, Sogdians never formed a large empire like some of their neighbors.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Period (327–145 BC)

Bottom: a copy of a coin of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I, from Sogdiana; the writing on the back is in Aramaic script.

Sogdia was a strong border region that protected the Persians from nomadic tribes. In 327 BC, Alexander the Great captured the Sogdian Rock, a famous fortress. Oxyartes, a Sogdian nobleman, had hoped to keep his daughter Roxana safe there. But after the fortress fell, Roxana married Alexander and became one of his wives. Her name, Roshanak, means "little star."

A Sogdian warlord named Spitamenes led a rebellion against Alexander. However, Alexander and his generals defeated this uprising. To prevent future revolts, Alexander encouraged his soldiers to marry Sogdian women. For example, Apama, Spitamenes' daughter, married Seleucus I Nicator, who later founded the Seleucid Empire.

After Alexander, Sogdia became part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This kingdom broke away from the Seleucid Empire in 248 BC.

Saka and Kushan Periods (146 BC–260 AD)

Around 145 BC, nomadic groups like the Sakas and then the Yuezhi took over Sogdia. The Yuezhi later formed the powerful Kushan Empire, which stretched from Sogdia to India. The Kushan Empire became a major center for trade in Central Asia.

A Chinese mission led by Zhang Qian visited the Yuezhi in 126 BC. Zhang Qian's detailed report gave important information about Central Asia at that time.

The Kushans worked with the Chinese against nomadic attacks. For example, they allied with the Han dynasty general Ban Chao in 84 AD against the Sogdians, who were supporting a revolt in Kashgar.

-

Model of a Saka cataphract armour with neck-guard, from Khalchayan. 1st century BCE. Museum of Arts of Uzbekistan, nb 40.

Sasanian Rule (260–479 AD)

Not much is known about Sogdia during the Parthian Empire. However, the later Sasanian Empire of Persia conquered Sogdia around 260 AD. An inscription from Shapur I states that "Sogdia, to the mountains of Tashkent" was his territory. This shows that Sogdia was the northeastern border of the Sasanian Empire. But by the 5th century, another group, the Hephthalite Empire, took control of the region.

Hephthalite Control (479–557 AD)

The Hephthalites conquered Sogdia around 479 AD. They may have built large fortified cities in Sogdiana, such as Bukhara and Panjikent. The Hephthalites likely ruled through local leaders.

Sogdia became very wealthy during this time. It was at the center of a new Silk Road connecting China, the Sasanian Empire, and the Byzantine Empire. The Hephthalites acted as important middlemen in this trade. They hired local Sogdians to transport silk and other luxury goods.

Turkic Khaganates (557–742 AD)

The Turks of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Sasanians allied to defeat the Hephthalites around 557 AD. The Turks took control of the area north of the Oxus River, including Sogdia. Later, the Western Turkic Khaganate ruled Sogdia.

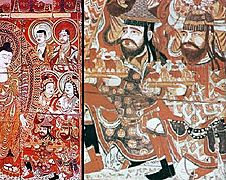

Archaeological findings suggest that the Turks became major trading partners with the Sogdians. This is seen in the tomb of the Sogdian trader An Jia. The Afrasiab murals in Samarkand also show Turks attending a reception by the Sogdian ruler Varkhuman in the 7th century. These paintings show that Sogdia was a very diverse place, with delegates from China and Korea also present. Around 650 AD, China conquered the Western Turks. Sogdian rulers became vassals of China until the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.

Arab Muslim Conquest (8th century AD)

Umayyad Caliphate (−750)

Qutayba ibn Muslim, a governor under the Umayyad Caliphate, began the Muslim conquest of Sogdia in the early 8th century. The Sogdians, with help from the Turkic Turgesh, managed to push out the Umayyad Arabs from Samarkand for a while. However, a large Arab force led by Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi eventually arrived. The Sogdian ruler of Samarkand, Gurak, decided it was best to surrender.

Some Sogdians, like Divashtich of Panjakent, resisted. Others fled to the Principality of Farghana, hoping for safety. But they were betrayed and many were killed by the Umayyad forces.

Abbasid Caliphate (750–819)

The Umayyad Caliphate fell to the Abbasid Caliphate in 750. The Abbasids quickly took control of Central Asia after winning the Battle of Talas against the Chinese Tang dynasty in 751. This battle also led to Chinese papermaking being introduced to the Islamic world.

This period saw the rise of the Samanid Empire (819–999). This Persian state, based in Bukhara, was mostly independent but still recognized the Abbasids. The Samanids continued the trading traditions of the Sogdians. However, the Sogdian language slowly disappeared, replaced by Persian. The original religions of Sogdia, like Zoroastrianism and Buddhism, also faded away as people converted to Islam. The Samanids also helped convert the surrounding Turkic peoples to Islam.

Samanids (819–999)

The Samanids ruled the Sogdian region from about 819 to 999. Their capital was first Samarkand and then Bukhara.

Turco-Mongol Conquests: Kara-Khanid Khanate (999–1212)

In 999, the Samanid Empire was conquered by the Kara-Khanid Khanate, a Turkic power.

From 1212, the Kara-Khanids in Samarkand were taken over by the Khwarazmian Empire. Soon after, the Mongol Empire led by Genghis Khan invaded. He destroyed the once-thriving cities of Bukhara and Samarkand. However, Samarkand later saw a revival in 1370. It became the capital of the Timurid Empire under the ruler Timur. He brought skilled workers and thinkers from all over Asia to Samarkand, making it a major trade and cultural center.

Sogdian economy and diplomacy

Sogdia's role in the Silk Road

Most merchants on the Silk Road did not travel the entire route. Instead, they traded goods through middlemen in oasis towns. However, the Sogdians created a vast trading network stretching from Sogdiana all the way to China. They were such skilled traders that people in the Kingdom of Khotan called all merchants "suli," meaning "Sogdian."

The Sogdians learned their trading skills from the Kushans. They initially controlled trade in the Fergana Valley. After the Kushan Empire declined, the Sogdians became the main middlemen.

Sogdia was not a country with fixed borders. It was a network of city-states, connecting Sogdiana to Byzantium, India, and China. Chinese contact with Sogdiana began with the explorer Zhang Qian during the Han dynasty. Zhang Qian wrote about his visit to Central Asia, calling the Sogdian area "Kangju."

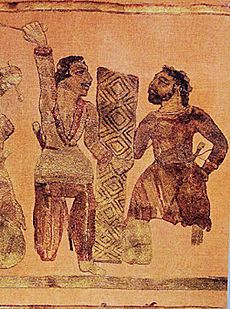

Right image: Detail of a mural from Varakhsha, 6th century AD, showing elephant riders fighting tigers and monsters.

After Zhang Qian's visit, trade between China and Central Asia grew. Many Chinese missions were sent in the 1st century BC. The Sogdians also acted as middlemen for the silk trade between China and the Parthian Empire. They played a major role in Silk Road trade until the 10th century. Their language even became a common language for trade across Asia.

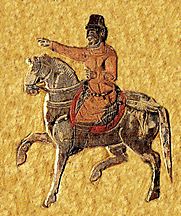

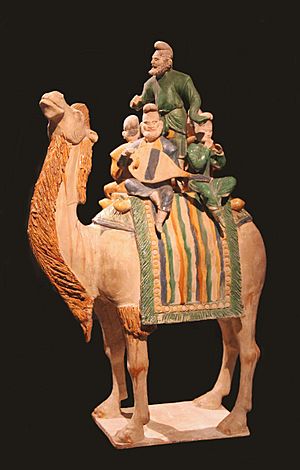

Right image: ceramic figurine of a Sogdian merchant in northern China, Tang dynasty, 7th century AD

Right image: Chinese-influenced Sogdian coin, from Kelpin, 8th century, British Museum

Sogdians from Samarkand became very important traveling merchants. They helped spread faiths like Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism along the Silk Road. Chinese records describe Sogdians as "skilled merchants" who learned their trade at a young age. By the 4th century, they may have controlled trade between India and China.

In 568 AD, a Sogdian delegation traveled to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. They offered silk as a gift and proposed an alliance against Persia. The Byzantine emperor agreed, which helped establish direct silk trade.

Suyab and Talas in modern-day Kyrgyzstan were key Sogdian centers in the north. Their trade was protected by the powerful Göktürks. Sogdian trade continued into the 9th century. For example, the ruler of the Second Turkic Khaganate seized goods like camels, silver, and gold from Sogdia during a raid.

In the 10th century, Sogdiana became part of the Uyghur Khaganate. The Uyghurs received large amounts of silk from China in exchange for horses. They relied on Sogdians to sell this silk further west. The Uyghurs also adopted Sogdian writing and religions like Manichaeism and Buddhism.

Many Sogdians settled in the Hexi Corridor in China during the 5th and 6th centuries. They kept some self-rule and had an official administrator called a Sabao. This shows their importance to China's economy. Chinese documents show that Sogdian merchants were involved in most trade deals in the Turpan region. They brought goods like grapes, alfalfa, and Sasanian silverware to China. In return, they traded for Chinese paper, copper, and silk.

The Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang noted in the 7th century that Sogdian boys learned to read and write at age five. However, they used these skills mostly for trade. Xuanzang also mentioned Sogdians working as farmers, carpet weavers, glassmakers, and woodcarvers.

Sogdian merchants and officials in China

Some Sogdians settled in China for many generations. Many lived in Luoyang, the capital of the Jin dynasty. However, they fled when the Jin dynasty lost control of northern China in 311 AD.

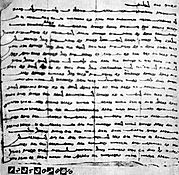

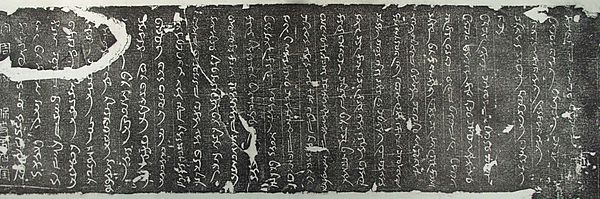

Letters found by Aurel Stein show that Sogdians faced challenges in China. One letter, from a Sogdian woman named Miwnay, describes how her husband abandoned her and their daughter. She was forced to become a servant. Another letter describes how many Sogdians and Indians in Luoyang died during a rebellion.

Still, some Sogdians remained in China. When the Northern Liang were defeated in 439 AD, many Sogdians were moved to the Northern Wei capital of Datong. This helped increase trade and cultural exchange.

Other Sogdians came from the west and became important in Chinese society. The Bei shi describes a Sogdian who became a sabao (caravan leader) and later a high-ranking minister. Sogdians became very influential non-Chinese groups in China during the Tang dynasty.

Sogdian envoys and merchants settled in China, marrying Chinese women and buying land. They built Zoroastrian temples in areas where many Sogdian families lived. The leaders of these communities, the sabao, became part of the official government.

Sogdian families in China built impressive tombs with special inscriptions. These tombs mixed Chinese burial styles with Zoroastrian customs. Sogdian tombs are among the most luxurious of that time, showing that the Sogdian Sabao were very wealthy.

Sogdians also served as soldiers in the Tang military. An Lushan, whose father was Sogdian, became a military governor. He led a major rebellion (755–763 AD) that caused a lot of trouble for the Tang dynasty. Many Sogdians supported this rebellion, and afterward, some were killed or changed their names to hide their Sogdian background.

Despite the rebellion, Sogdians continued to trade actively in China. However, many had to hide their ethnic identity. For example, An Chongzhang, a Minister of War, changed his name to Li Baoyu to avoid being associated with the rebel leader.

Nestorian Christians, like the priest Yisi from Bactria, helped the Tang dynasty defeat the An Lushan rebellion. The Tang dynasty rewarded Yisi and the Nestorian Church.

In the Tang and later dynasties, a large Sogdian community lived in Dunhuang, a major Buddhist center. Dunhuang was a multicultural city with many manuscripts in Chinese, Tibetan, Sogdian, and other languages.

The influence of Sogdians in Dunhuang is seen in Chinese texts written from left to right, like the Sogdian alphabet. Sogdians in Dunhuang also formed community groups and met at Sogdian-owned taverns. In Turfan, Sogdians worked as farmers, soldiers, painters, and leather crafters. Their migration to Turfan increased after the Muslim conquests of Persia and Samarkand.

There were nine main Sogdian clans, identified by their Chinese surnames. Each surname came from a different Sogdian city-state. For example, Shí (石) came from Chach (modern Tashkent), and Kāng (康) came from Samarkand.

Sogdian language and culture

The 6th century is considered the peak of Sogdian culture. At this time, Sogdians were well-known as traveling merchants, spreading goods, culture, and religion. The valley around Samarkand kept its Sogdian name during the Middle Ages. Arab geographers even called it one of the four most beautiful regions in the world.

Sogdian art

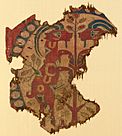

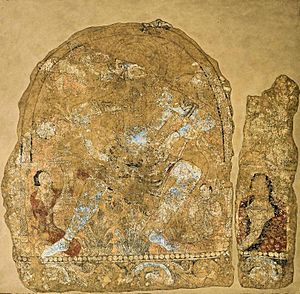

The Afrasiab paintings from the 6th to 7th centuries in Samarkand are rare examples of Sogdian art. These paintings show daily life and events, like the arrival of foreign ambassadors. They are found in the ruins of noble homes. The oldest Sogdian wall murals are from the 5th century in Panjakent, Tajikistan. Sogdian art helps us understand their religious beliefs. For example, Buddhist Sogdians sometimes included their own Iranian gods in their Buddhist art.

Sogdian language

The Sogdians spoke an Eastern Iranian language called Sogdian. It was similar to Bactrian and Khwarazmian. Sogdian was also important in the city-state of Turfan in Northwest China. The Bugut inscription from Mongolia shows that Sogdian was an official language of the First Turkic Khaganate around 581 AD.

Sogdian was written using three main scripts: the Sogdian alphabet, the Syriac alphabet, and the Manichaean alphabet. All of these came from the Aramaic alphabet. The Sogdian alphabet later became the basis for the Old Uyghur alphabet and the Mongolian script.

Today, the Yaghnobi people in Tajikistan still speak a language descended from Sogdian. Most Sogdian people, however, mixed with other groups like the Bactrians and Persians. They eventually started speaking Persian. The modern Tajik language has many words that came from Sogdian.

Sogdian clothing

Early medieval Sogdian clothing changed over time. From the 5th to 6th centuries, it was influenced by the Hephthalites. In the 7th and early 8th centuries, Turkic styles became common. This happened after the Western Turkic Khaganate took control and included local Sogdian nobles in their government.

Sogdian clothes were often tight-fitting, with narrow waists and wrists. For men and young girls, the clothes emphasized wide shoulders. For noble women, the styles were more complex. Over centuries, Sogdian clothing changed due to Islamic influences. Turbans, kaftans, and sleeved coats became more common.

Sogdian religious beliefs

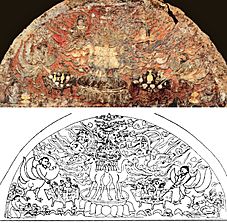

Right: A Zoroastrian fire worship ceremony, depicted on the Tomb of Anjia, a Sogdian merchant in China.

Sogdians practiced many different religions. Zoroastrianism was likely their main faith. Evidence for this includes murals showing people making offerings at fire altars. Also, ossuaries (containers for bones) have been found, which were used in Zoroastrian rituals. In Turpan, Sogdian burials combined Chinese customs with Zoroastrian ones. They would allow bodies to be cleaned by scavengers before burying the bones. They also sacrificed animals to Zoroastrian gods. Zoroastrianism remained strong until the Islamic conquest, after which Sogdians gradually converted to Islam.

Most Sogdian religious texts found in China are Buddhist, Manichaean, or Nestorian Christian. Only a few Zoroastrian texts have been found. However, Sogdian tombs in China from the 6th century show mostly Zoroastrian symbols.

Sogdians were known for their religious diversity. They were important in translating Buddhist texts into Chinese. However, Buddhism did not become very popular in Sogdiana itself. Sogdian Christian texts have been found in the Bulayiq monastery. There are also many Manichaean texts from Qocho.

The Sogdians also practiced Manichaeism, a religion founded by Mani. They helped spread this faith among the Uyghurs. The Uyghur Khaganate (744–840 AD) had close ties with China. They relied on Sogdian merchants to sell silk. This led many Uyghurs to adopt Manichaeism from the Sogdians.

Five Hindu deities were known to be worshipped in Sogdiana: Brahma, Indra, Mahadeva (Shiva), Narayana, and Vaishravana. These gods were known by their Sogdian names.

When Marco Polo visited Zhenjiang, China, in the late 13th century, he noted many Christian churches. A Chinese text confirms this, stating that a Sogdian named Mar-Sargis founded six Nestorian Christian churches there. Nestorian Christianity had been in China since the Tang dynasty, brought by a Persian monk named Alopen in 653. The earliest Christian texts translated into Sogdian date back to the 5th century.

Sogdian communities and notable people

Sogdians lived in various places outside Sogdiana.

- A community of Sogdian merchants lived in Ye during the Northern Qi era.

- A Sogdian community existed in Jicheng (Beijing) during the Tang dynasty.

Famous Sogdians

- Amoghavajra: A very influential Buddhist monk and translator in Chinese history. His mother was of Sogdian descent.

- An Lushan: A military leader of Sogdian and Turkic origin during the Tang dynasty. He led a major rebellion that greatly weakened the Tang dynasty.

- Apama: Daughter of the Sogdian warlord Spitamenes. She married Seleucus I Nicator, who founded the Seleucid Empire.

- Divashtich: An 8th-century ruler of Panjakent.

- Fazang: A Buddhist monk and philosopher from the 7th century, who founded the Huayan school of Buddhism.

- Gurak: An 8th-century ruler of Samarkand.

- Mi Fu: A famous painter, poet, and calligrapher of the Song dynasty.

- Oxyartes: A Sogdian warlord and the father of Roxana, who married Alexander the Great.

- Roxana: The main wife of Alexander the Great.

- Spitamenes: A Sogdian warlord who led a rebellion against Alexander the Great.

- Tarkhun: An 8th-century ruler of Samarkand.

|

See also

In Spanish: Sogdiano para niños

In Spanish: Sogdiano para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |