Chinese ceramics facts for kids

Chinese ceramics are super important types of art and pottery from China. They include everything from building bricks and tiles to fancy porcelain dishes made for emperors and for selling all over the world.

Chinese pottery has been made for a very long time, since before ancient dynasties. The first pottery was even made during the Stone Age! Porcelain was invented in China, and it's so famous that we still call fine dishes "china" today.

Most Chinese ceramics, even the really good ones, were made in huge factories. Because of this, we don't know the names of many individual potters. Many important workshops belonged to the emperor. Lots of Chinese porcelain was sent out as diplomatic gifts or for trade. At first, it went to East Asia and the Islamic world. Later, from the 1500s, it went to Europe. Chinese ceramics had a huge impact on pottery in other places.

Over time, Chinese ceramics were made for different groups. Some were for the emperor, some for wealthy Chinese buyers, and others for everyday people or for export. Some special types were also made for tombs or for use in temples.

Contents

Types of Chinese Pottery

The first Chinese pottery was earthenware. This type of pottery is still made for everyday things. But it was used less for fancy items over time. Stoneware, which is fired at higher temperatures and doesn't let water through, was developed very early. It was used for fine pottery in many areas. For example, the tea bowls from Jian ware and Jizhou ware during the Song dynasty are stoneware.

What is Porcelain?

In the West, porcelain means any white, see-through ceramic. It doesn't matter what it's made of or what it's used for. In China, they have two main types of ceramics: high-fired (called cí) and low-fired (called táo). This means that what we call stoneware is often grouped with porcelain in China. Sometimes, you might hear "porcellaneous" for stoneware that looks like porcelain.

Chinese pottery can also be called northern or southern. China has two different land areas with different geology. This led to different materials for making ceramics. For example, the north doesn't have "porcelain stone," which is needed for true porcelain. Pottery from the north and south usually look different. The kilns were also different. In the north, they used coal for fuel, and in the south, they used wood. This often changed how the pottery looked.

Materials Used

Chinese porcelain is mostly made from these materials:

- Kaolin: A main ingredient, mostly made of a clay mineral called kaolinite.

- Porcelain stone: Decomposed rocks that look like mica or feldspar.

- Feldspar

- Quartz

How Pottery Was Made

The word porcelain doesn't have one clear meaning in Chinese ceramics. This makes it tricky to know exactly when the first Chinese porcelain was made. Some say it was during the late Han dynasty (100–200 AD), others say later.

Kiln technology was always super important for Chinese pottery. The Chinese created good kilns that could fire pottery at about 1,000°C (1,832°F) before 2000 BC. These were updraft kilns, often built underground. Two main types of kilns were used until modern times. The dragon kiln was used in hilly southern China. It was long, thin, and built on a slope, usually burning wood. The horseshoe-shaped mantou kiln was used in the northern plains. It was smaller and more compact. Both could reach temperatures of 1,300°C (2,372°F) or more, which is needed for porcelain.

History of Chinese Ceramics

Early Pottery

Pottery found in a cave in Jiangxi province is 20,000 years old, making it some of the oldest pottery ever found! Another discovery in southern China is from 17,000 to 18,000 years ago.

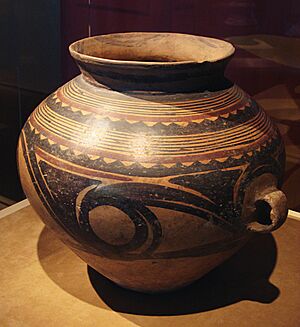

By the Middle and Late Neolithic period (around 5000 to 1500 BCE), most larger cultures in China were farmers. They made many beautiful and often big pots. These were often brightly painted or decorated by cutting designs into them. The designs were abstract or showed animals like fish. The unique Majiayao pottery had orange bodies and black paint. It was known for smooth textures, thin walls, and shiny surfaces. The pots found have almost no flaws, showing how carefully they were made. The potter's wheel seems to have been invented in China during the 4th millennium BCE. Before that, large pots were made by coiling clay.

Most pots found are in burials. Sometimes they held human remains. By 4100–2600 BCE, in the Dawenkou culture, shapes that later became famous for Chinese ritual bronzes started to appear.

Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD)

Some Chinese experts say the first porcelain was made in Zhejiang province during the Eastern Han dynasty. Pieces found from Eastern Han kiln sites were fired at temperatures from 1,260 to 1,300°C (2,300 to 2,372°F). Even as far back as 1000 BC, "proto-porcelain" was made using some kaolin and fired at high temperatures. The line between these and "true porcelain" is not always clear.

During the late Han years, a special art form called hunping, or "soul jar," became popular. These were burial jars with sculptures on top. This type of jar became very common in the following Jin dynasty (266-420) and Six Dynasties.

Tomb figures were popular across society. They often showed model houses and farm animals. Green-glazed pottery, using lead-glazed earthenware, was used for some of these figures. However, this glaze was poisonous, so it wasn't used for dishes people ate from.

-

Lion-shaped candle holder from Western Jin around the 4th century CE

Sui and Tang Dynasties (581–907 AD)

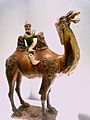

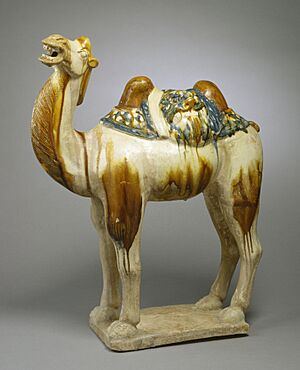

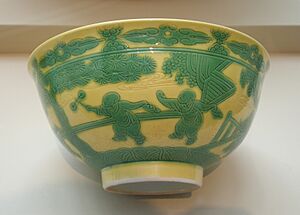

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, many types of ceramics were made, both low-fired and high-fired. These included the last important fine earthenwares in China, mostly lead-glazed sancai (three-colour) wares. Many famous and lively Tang dynasty tomb figures, like camels and horses, are made of sancai. These figures were only made for rich people's tombs near the capital. The sancai glaze was less toxic than in the Han dynasty, but still probably not safe for dining dishes.

In the south, pottery from the Changsha Tongguan Kiln Site was important because it was the first to regularly use underglaze painting. Examples have been found in many places in the Islamic world.

Yue ware was the top high-fired, lime-glazed celadon of this time. It had very fancy designs and was favored by the emperor's court. The same was true for northern porcelains from Henan and Hebei provinces. These were the first to truly fit the Western idea of porcelain, being both pure white and see-through. The white Xing ware and green Yue ware were thought to be the best ceramics from north and south China. An Arab traveler named Suleiman wrote in 851 AD that the Chinese made vases "as transparent as glass."

Pottery from this era was known for its bright colors. Later periods often used simpler styles because of new ideas like Neo-Confucianism, which preferred modesty over fancy displays.

Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD)

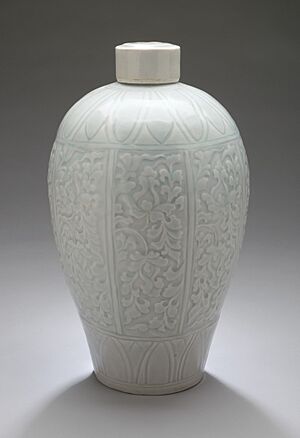

Pottery from the Song dynasty is highly respected in Chinese history, especially from the "Five Great Kilns". Song pottery focused on subtle glaze effects and elegant shapes. Other decorations, if any, were usually shallow reliefs. At first, these were carved with a knife, but later moulds were used. Painting was mostly seen in the popular Cizhou ware. Underglaze blue was not popular because Confucian ideas favored simplicity, and blue designs were seen as too fancy.

Green ware or celadons were popular in China and for export. Yue ware was followed by Northern Celadon and then Longquan celadon in the south. White and black wares were also important, especially in Cizhou ware. There were also colorful types, but the best ceramics for the court were plain, focusing on glaze and shape. Many styles developed, and successful ones were copied. Important kiln sites and stoneware styles included Ru, Jun, Southern Song Guan (official ware), Jian, and Jizhou. White porcelain continued to get better, with Ding ware and then qingbai becoming popular.

The Liao, Xia, and Jin dynasties were founded by nomadic people who took over parts of China. Pottery continued under their rule, mixing their art with Chinese styles to create new looks.

Most fine pottery from these regions was high-fired. Some earthenware was made because it was cheaper and had more colorful glazes. Potters used local clay. If the clay was dark, they would cover it with white slip before glazing to make a fine white body.

Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

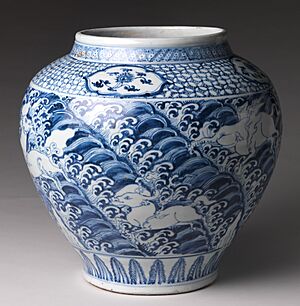

The Mongol Yuan dynasty moved artists around their empire. This brought a big new style from the Islamic world: blue and white porcelain. This pottery used underglaze painting with cobalt. It was called the "last great innovation in ceramic technology." Underglaze painting had been used before, especially in Cizhou ware, but it was seen as a bit common. The finest ceramics were plain, with perfect shapes and subtle glazes.

This was very different from the bright colors and complex designs of the Yuan dynasty. These designs were inspired by Islamic art, especially metalwork, but the animal and plant patterns were still Chinese. At first, these were mostly made for export. But they became popular in China too. This style has been made ever since, in China and worldwide.

Because of this, and better water transport, pottery making started to focus near kaolin deposits, like Jingdezhen. Jingdezhen slowly became the most important center for porcelain, a position it still holds. Production grew a lot, and kilns became like factories, with many people doing different jobs. This was early mass production. Other types of pottery, like Longquan celadon and Cizhou ware, also continued to do well.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

The Ming dynasty was an amazing time for new ideas in pottery. Kilns tried new designs and shapes, loving color and painted patterns. The Yongle Emperor (1402–24) was especially curious about other countries. He liked unusual shapes, many inspired by Islamic metalwork. During the Xuande period (1426–35), they improved the cobalt used for blue underglaze.

Before this, cobalt was bright but tended to bleed. By adding manganese, the color was duller but the lines were sharper. Xuande porcelain is now considered some of the best Ming pottery. Enamelled decoration was perfected under the Chenghua Emperor (1464–87). By the late 1500s, Chenghua and Xuande pieces were so popular that their prices were almost as high as ancient Song dynasty pottery.

Besides these new decorations, the late Ming dynasty saw a big shift to a market economy. Porcelain was exported worldwide like never before. Jingdezhen became the main place for large-scale porcelain exports to Europe starting with the Wanli Emperor (1572–1620). By this time, kaolin and pottery stone were mixed in equal amounts. Kaolin made the pottery very strong and white, which was popular for blue-and-white wares. Pottery stone could be fired at a lower temperature (1,250°C / 2,282°F) than kaolin mixes (1,350°C / 2,462°F). These differences were important because the large southern kilns had varying temperatures.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

The long wars between the Ming and Qing dynasties broke the imperial kiln system. This forced managers to find new markets. The Transitional porcelain (around 1620 to 1680s) had a new painting style, mostly blue and white. It showed new subjects like landscapes and figures painted very freely. Later in this period, Europe joined the export markets.

The Qing dynasty made many different porcelain styles, building on Ming innovations. The most exciting new area was the wider range of colors available, mostly in overglaze enamels. A very important trade in Chinese export porcelain with the West grew. The emperor's court liked many styles, still favoring plain colored pottery, but now in bright new colors. Special glaze effects were highly valued. New ones were developed, and classic Song wares were copied very skillfully. But the court also accepted painted scenes in blue and white and the new bright colors. Jingdezhen's technical quality was very high, though it dropped a bit by the mid-1800s.

Designs often became more complex and detailed. Generally, the Ming period is seen as having greater art. By the 1700s, the art stopped changing in big ways, and the energy in painting lessened.

A Jesuit missionary named Père François Xavier d'Entrecolles lived in Jingdezhen in the early 1700s. He wrote detailed letters about how porcelain was made. He described how pottery stones were crushed, refined, and made into white bricks. He also explained how china clay (kaolin) was refined, glazed, and fired. He wanted to share this knowledge with Europe.

In 1743, during the Qianlong Emperor's rule, an imperial supervisor named Tang Ying wrote a book called Twenty Illustrations of the Manufacture of Porcelain. The original pictures are lost, but the text is still available.

Famous Chinese Pottery Styles

Tang Burial Wares

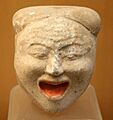

Sancai means "three-colors": green, yellow, and a creamy white. These were lead-based glazes. Other colors, like cobalt blue, could also be used. In the West, Tang sancai wares were sometimes called egg-and-spinach.

Sancai wares were made in northern China using white and buff-firing clays. They were fired at a lower temperature than other white wares of the time. Tang dynasty tomb figures, like the famous camels and horses, were made in parts using moulds. The parts were then joined with clay. They were either painted in sancai or just coated in white slip, often with paint added over the glaze. This paint has usually fallen off now. Sometimes, potters added unique details by hand-carving.

Greenwares or Celadon Wares

Celadon wares are named for their glaze. It uses iron oxide to create many colors, mostly jade or olive green. But it can also be brown, cream, or light blue. This range of colors is similar to jade, which was always the most prized material in Chinese art. This is why celadon was so attractive to the Chinese. Celadons are plain or decorated with relief designs, which can be carved or moulded. Sometimes used by the emperor's court, celadons were also popular with scholars and the middle class. Huge amounts were also exported. Important types include: Yue ware, Yaozhou ware, Ru ware, Guan ware, and Longquan celadon.

Jian Ware

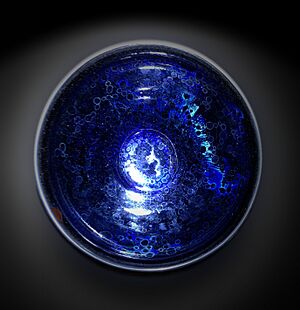

Jian Zhan blackwares, mostly tea cups, were made in Jianyang, Fujian province. They were most popular during the Song dynasty. These wares were made using local, iron-rich clays and fired in an oxidizing atmosphere at about 1,300°C (2,372°F). The glaze was made from similar clay, but with wood-ash added. At high temperatures, the melted glaze separated to create a pattern called "hare's fur." When Jian wares were tilted for firing, glaze drips ran down the sides, showing where the liquid glaze pooled.

Jian tea wares from the Song dynasty were also loved and copied in Japan, where they were called tenmoku wares.

Jizhou Ware

Jizhou ware was stoneware, mostly used for drinking tea. It was famous for its glaze effects, like a "tortoiseshell" glaze. Potters also used real leaves as glaze resists. The leaf would burn away during firing, leaving its outline in the glaze.

Ding Ware

Ding ware was made in Ding County, Hebei Province. It was already being made when the Song emperors came to power in 940. Ding ware was the best porcelain in northern China at the time, and the first to be used by the imperial palace. It has a white body, usually covered with a clear glaze that dripped and collected in "tears." (Some Ding ware was black or brown, but white was more common). Ding ware focused on elegant shapes rather than flashy decoration. Designs were simple, either carved or stamped into the clay before glazing. Because dishes were stacked in the kiln, their edges were left unglazed. These edges had to be rimmed with metal like gold or silver when used as tableware. Later, a writer said this flaw led to it losing favor with the emperor.

Ru Ware

Like Ding ware, Ru ware (ju) was made in North China for the emperor. The Ru kilns were near the Northern Song capital, Kaifeng. Ru pieces have small amounts of iron oxide in their glaze. When fired in a reducing atmosphere, this turns them greenish. Ru wares come in colors from almost white to a deep robin's egg blue. They often have reddish-brown crackles. These crackles happen when the glaze cools and shrinks faster than the pottery body, causing it to crack. An art historian noted that the Song dynasty was the first time people saw crackling as a good thing, not a flaw. Over time, the pottery bodies became thinner, and glazes became thicker.

The Song imperial court lost access to the Ru kilns when they fled south from invaders. The emperor then started Guan yao ('official kilns') to make copies of Ru ware. However, Ru ware is still remembered as being unmatched.

Jun Ware

Jun ware (chün) was another type of porcelain used at the Northern Song court. It has a thicker body than Ding or Ru ware. Jun is covered with a turquoise and purple glaze that looks so thick it seems to be melting off the golden-brown body. Jun pottery is also much stronger. Both types were liked by Emperor Huizong of Song. Jun production was centered in Yuzhou, Henan Province.

Guan Ware

Guan ware means "official" ware. So, some Ru, Jun, and even Ding wares are Guan in a general sense because they were made for the court. But usually, the term in English means pottery made by an official, imperially run kiln. This didn't start until the Southern Song dynasty fled south to Lin'an. During this time, the pottery walls became very thin, with the glaze being thicker than the wall. The clay in the hills around Lin'an was brownish, and the glaze was very thick.

Ge Ware

Ge ware (ko), meaning "big-brother" ware, comes from a legend about two brothers. One made typical celadons, and the elder made ge ware in his own kiln. A Ming dynasty writer said that the ge kiln used clay from the same place as Guan ware, which makes them hard to tell apart. Ge ware usually has a grayish-blue glaze that is fully opaque and almost matte. Its crackle pattern is very noticeable, often in bold black. While similar to Guan ware, Ge typically has a grayish-blue glaze that is fully opaque with an almost matte finish.

Qingbai Wares

Qingbai wares (also called 'yingqing') were made at Jingdezhen and other southern kilns from the Northern Song dynasty until the 1300s. They were then replaced by blue and white wares. Qingbai in Chinese means "clear blue-white." The qingbai glaze is a porcelain glaze, made using pottery stone. It's clear but has small amounts of iron. When put over a white porcelain body, it creates a greenish-blue color, which gives it its name. Some pieces have carved or moulded decorations.

The Song dynasty qingbai bowl shown was probably made at Hutian, a village in Jingdezhen. This was also where the imperial kilns were set up in 1004. The bowl has carved decoration, possibly showing clouds or reflections in water. The body is white, see-through, and feels like very fine sugar. This means it was made using crushed pottery stone, not pottery stone and kaolin. The glaze and body were fired together in a saggar (a lidded ceramic box) in a large wood-burning dragon kiln.

Many Song and Yuan dynasty qingbai bowls were fired upside down in special saggars. This technique was first used at the Ding kilns. The rims of these wares were left unglazed but often had bands of silver, copper, or lead.

A famous example of qingbai porcelain is the Fonthill Vase. It was made at Jingdezhen around 1300. It was probably sent as a gift to Pope Benedict XII by a Chinese emperor in 1338. The vase had fancy silver-gilt mounts added in Europe in 1381. These mounts are now lost. The vase is in the National Museum of Ireland.

Blue and White Wares

Blue and white wares are glazed with a clear porcelain glaze. The blue decoration is painted onto the porcelain body before glazing. It uses very finely ground cobalt oxide mixed with water. After painting, the pieces are glazed and fired.

It's believed that underglaze blue and white porcelain was first made in the Tang dynasty. Only three complete pieces of Tang blue and white porcelain are known. But pieces from the 8th or 9th century have been found in Yangzhou. In 1957, a Northern Song bowl with underglaze blue was found in Zhejiang province. More pieces have been found since.

In 1975, pieces with underglaze blue were found at a kiln site in Jiangxi. In the same year, a blue and white urn from a tomb dated 1319 was found in Jiangsu province. It's interesting that a Yuan funerary urn from 1338, decorated with underglaze blue and red, still looks Chinese. But by this time, large-scale production of blue and white porcelain in the Mongol style had begun at Jingdezhen.

Starting in the early 1300s, blue and white porcelain quickly became the main product of Jingdezhen. It reached its best quality during the later years of the Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722) and is still an important product today.

The tea caddy shown is a good example of blue and white porcelain from the Kangxi period. The clear glaze shows the very white body. The cobalt decoration, applied in many layers, has a beautiful blue color. The decoration, showing a wise person in a landscape with lakes, mountains, and rocks, is typical of the period. The piece was fired in a saggar (a lidded ceramic box to protect it) in a wood-burning egg-shaped kiln, at about 1,350°C (2,462°F).

Unique blue-and-white porcelain was sent to Japan. There, it's known as Tenkei blue-and-white ware or ko sometsukei. This pottery was likely specially ordered by tea masters for the Japanese tea ceremony.

Blanc de Chine

Blanc de Chine is a type of white porcelain made at Dehua in Fujian province. It has been made from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) until now. Large amounts arrived in Europe in the early 1700s and were copied in places like Meissen.

The Fujian coast was a main area for exporting ceramics. Over 180 kiln sites have been found, dating from the Song dynasty to today.

From the Ming dynasty, porcelain was made that combined glaze and body to create "ivory white" and "milk white" colors. Dehua porcelain has very little iron oxide. This allows it to be fired in an oxidizing atmosphere to a warm white or pale ivory color.

The porcelain body is not very flexible, but many shapes were made from it. Products included figures, boxes, vases, jars, cups, bowls, fish, lamps, censers, flowerpots, animals, and tea sets. Many figures were made, especially religious ones like Guanyin and Maitreya.

Today, Dehua porcelain factories make modern figures and tableware. During the Cultural Revolution, Dehua artists made perfect statues of Mao Zedong and Communist leaders. These figures later became less popular but are now collected by foreigners.

Famous blanc de Chine artists, like He Chaozong from the late Ming period, signed their work. Their pieces included finely sculpted figures, cups, bowls, and incense holders.

Many of the best blanc de Chine examples are in Japan. There, the white type was called hakugorai or "Korean white," a term often used in tea ceremony circles. The British Museum in London has a large collection of blanc de Chine.

Painted Colors

Chinese court taste long preferred plain colored pottery. Even though blue and white porcelain was accepted by the Yuan dynasty court, more colorful styles took much longer to become popular. At first, blue from cobalt was almost the only color that could handle the high heat of porcelain firing without changing color. But slowly (mostly during the Ming period), other colors were found. Or, people accepted the extra cost of a second firing at a lower temperature to set overglaze enamels. Copper-reds could look great underglaze, but many pieces would turn out grey and had to be thrown away. Eventually, underglaze blue and overglaze red became the usual way to get the same look.

Overglaze painting, often called "enamels," was widely used in popular Cizhou ware stoneware. It was sometimes tried by kilns making pottery for the court. But it wasn't until the 1400s, under the Ming, that the doucai technique was used for imperial wares. This combined underglaze blue outlines with overglaze enamels in other colors. The wucai technique was similar, using underglaze blue more for highlights.

Two-color wares, using underglaze blue and one overglaze color (usually red), also looked very good. Many other methods using colored glazes were tried, often with images lightly carved into the pottery. The fahua technique outlined colored decorations with raised lines of slip. The subtle "secret" (an hua) technique used very light carvings that were hard to see. As more glaze colors became available, the love for plain colored pottery returned. Many special glazing effects were developed, including crackle and spotty effects made by blowing powdered color onto the piece.

Color Classifications: The Famille Groups

Later, groups of enamel colors were used on Chinese porcelain. These are known by their French names: famille jaune, noire, rose, and verte. These names come from the main color in each group. Many of these were export wares, but some were made for the Imperial court.

- Famille verte (meaning "green family"), used in the Kangxi period (1661–1722), uses green and iron red with other overglaze colors. It grew from the wucai ("five colors") style.

- Famille jaune is a type of famille verte that uses yellow as the background color.

- Famille noire is another type of famille verte, but it uses a black background.

- Famille rose (meaning "pink family"), introduced late in the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (around 1720), mainly used pink or purple. It stayed popular throughout the 1700s and 1800s. Many European factories also copied it. Famille rose enamel ware allowed for more colors and shades than before, making more complex pictures possible.

- Examples of famille verte works

-

Famille verte dish, Kangxi period (1661–1722)

-

Wucai vase, Shunzhi period, around 1650–1660

-

Wucai export plate, Kangxi period, around 1680

-

Wucai export plate, Kangxi period, around 1680

- Examples of famille rose works

-

Soft paste famille rose flower holder, Jingdezhen, Qianlong period (1735–96)

-

Double Peacock Dinner Service export: famille rose service with peacocks over a rock, late 18th century

-

Moon flasks in famille rose, Jingdezhen, Yongzheng reign (1723–35)

Stoneware

Pottery called stoneware in the West is usually seen as porcelain in China. China doesn't have a separate stoneware group. So, their definition of porcelain is different, covering all hard, high-fired pottery. Terms like "porcellaneous" are often used to describe pottery that is between stoneware and porcelain. Many high-fired stonewares were made very early. They included important pottery for the emperor and lots of everyday pots. They were usually famous for their glazes. Most of the celadon group, especially earlier ones, can be called stoneware. All classic Jian wares and Jizhou wares are also stoneware.

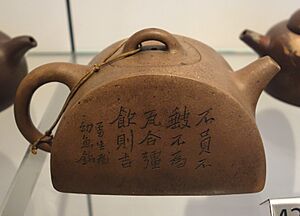

In contrast, Yixing clay teapots and cups from Yixing clay in Jiangsu province are usually left unglazed. They are not washed after use because the clay is believed to make the tea taste better, especially after long use. There are different clays, giving a range of colors. These pots are special because they are often signed by their potters, which is very rare in China. This might be because they were linked to the literati culture, which was strong in Jiangsu. The oldest known example is from a burial in 1533. Fancy decorated examples, often rectangular, were exported to Europe from the 1700s. These pots often had poems written on them. Besides teaware, fruit and other natural shapes were made as decorations. Production continues today, usually with simpler shapes.

The Ceramics Industry in the Ming Dynasty

Imperial and Private Kilns

The very first imperial kiln was set up in the 35th year of Hongwu's rule. Before that, there were no clear rules for state-ordered porcelain. The law said that if a lot of ceramics were needed, potters would be forced to work in the imperial kilns in Nanjing. If only a small amount was needed, private kilns in Raozhou could make them. In both cases, officials from the capital were sent to watch over the work. They made sure the quality was good and sent products back to the emperor. The imperial court set strict rules for styles and sizes. After 1403, imperial kilns were built and started making imperial porcelain on a large scale.

In the mid-Ming period, the demand for porcelain grew. The temporary officials couldn't handle it. So, in the Xuande period, the imperial factory in Jingdezhen was built. This factory had dorms, offices, and workshops. It also had wells, wood sheds, temples, and lounges for potters. It was not just a production site but also a government office.

The imperial factory had 23 departments. Each department was in charge of a different part of making ceramics. Work was divided by type, like large vessels, small vessels, painting, carving, and calligraphy. This division of labor meant that one piece of pottery could pass through many hands. This is why potters didn't sign their pieces like they did in private kilns. It also made sure all ceramics had a uniform style and size.

The number of imperial kilns changed during the Ming period. There were fewer than ten in the 1400s. Then the number grew to 58, then 62, and later dropped to 18.

Imperial orders wanted both unique designs and large quantities of porcelain. Different parts of the court expected specific designs. For example, yellow and green products with mythical flying creatures were asked for by the Directorate for Palace Delicacies. The need for both unique designs and mass production put a lot of pressure on kilns. Many had to ask private kilns to help meet the court's demands.

In the late Ming period, the system of forced labor in ceramics changed. People could pay money instead of working. Many good potters left the imperial kilns for private ones, where they were paid better. The late Ming period saw a big drop in the quality of imperial kiln pieces and a rise in private kilns.

Private kilns existed in the early Ming dynasty and their products were part of the government's tax income. Besides making ceramics for everyday use, private kilns also took orders from the imperial court. However, making and selling imperial-style ceramics in private kilns was strictly forbidden.

In the late Ming period, private kilns became more important as imperial kilns declined. Many skilled workers left the tough conditions of imperial kilns for private ones. Private kilns were more focused on business. Several private kilns became very popular among scholars who liked antique-style porcelain. Examples include the Cui kiln, Zhou kiln, and Hu kiln. Ceramics in the late Ming dynasty were made in high quality and quantity. This made Jingdezhen one of the earliest commercial centers in the world.

Competition in the porcelain industry exploded when government control lessened. Investors could put money into many types of production, especially crafts. In Jingdezhen, over 70% of the 100,000 families in the town were involved in the porcelain industry.

Life as a Potter

In the early Ming dynasty, people were divided into three groups: military, craftsmen, and peasants. Potters were craftsmen. Craftsmen families had to work their whole lives, and their status was passed down to their children.

In the early Ming period, when the court needed ceramics, workers were forced to join the imperial kilns. Most potters were chosen by local government and worked for three months every four years for free. Other workers were hired from nearby counties and paid regularly. They were usually assigned to different departments.

The imperial factory had 23 departments, each with managers and workers. Making porcelain was hard. More than half of the firings often resulted in spoiled pieces, which were thrown away. This created huge piles of porcelain fragments near Jingdezhen. It was important to control the fire to keep a constant temperature. The rules for potters in the imperial kiln were strict. Potters were punished for delays, smuggling, or making bad goods.

Many potters refused or ran away from being forced to work in the imperial kilns because they were overworked and underpaid. By the Xuande period, about 5,000 potters had escaped. In the first year of Jingtai, the number reached about 30,000. The government changed the rules so potters could pay money each month instead of working. This meant potters were no longer tied to the government. Many talented workers left for private kilns. The imperial kilns lost skilled potters, and the quality of their porcelain dropped a lot.

Starting in the ninth year of Jiajing, a new rule was put in place. The government provided materials and used private kilns to make porcelain. They paid the private kilns based on how much porcelain was made. However, the state often couldn't pay the full amount.

After Production

The growth of Chinese porcelain during the Ming dynasty needed a system for selling large amounts. Individual sales were important, but wholesale orders were even more so. Wholesale orders were the main support of the porcelain economy. Without these orders, which took months or a year to complete, there wouldn't have been enough demand.

Merchants who didn't know much about porcelain trade relied on brokers. Brokers introduced them to reliable kilns and helped negotiate prices. Brokers also helped kilns by checking if buyers were trustworthy. If a buyer was unreliable, word spread. This could ruin a buyer's reputation but helped the kilns succeed.

The court ordered porcelain for cooking, religious uses, and display. Since the court often used porcelain once and threw it away, imperial orders kept coming. Demand was often too high for kilns to meet, showing how important it was to produce a lot.

Fine porcelain was sent by sea and land to Southeast Asia, Japan, and the Middle East. The amount of foreign trade was huge. One record shows over 16 million pieces going through a Dutch East India Company. Land transport also showed how much work was involved. Dozens of carts from Mongolia, Manchuria, Persia, and Arabic countries were loaded with porcelain and other Chinese goods in the Ming capital. Some carts were 30 feet high! To protect hollow porcelain vases, they were filled with soil and beans. The growing bean roots helped the porcelain withstand pressure during transport.

Like the silk industry, the porcelain industry was known for its mass production. Potters from poorer backgrounds stuck to their old methods because trying new ones was risky. A new technique could mean losing a whole month's work. So, for these potters, changing their method was not an option. These potters were found outside Jingdezhen. For potters in Jingdezhen, international markets greatly influenced their work. These markets inspired new ideas. For example, Jingdezhen made ceramic versions of reliquaries, bowls, oil lamps, and stem-cups.

Foreign trade was not always good for potters. The further products traveled from Jingdezhen, the more vulnerable they became. One report tells of a Spanish voyage where about a fifth of a Chinese ship's crew was killed when attacked by a Spanish voyager. The two raided ships held many Chinese valuables, including porcelain.

International trade needed organization between chiefs and potters. In Southeast Asian trading ports, chiefs could set port fees and control interactions between rich merchants and foreign traders. By charging fees, chiefs profited from almost every deal. Potters making luxury porcelain had to follow the rules set by the chiefs.

Fakes and Copies

Chinese potters have a long history of copying designs from older pottery. While pottery with copied features might sometimes be hard to identify, they usually aren't considered fakes. However, fakes and copies have been made many times throughout Chinese ceramics history and are still made today.

Also, the reign marks of earlier emperors (usually from the Ming dynasty) were often put on Qing wares. Scholars often see this as a sign of respect, not an attempt to trick people. But they clearly did mislead people at the time and cause confusion.

- Copies of Song dynasty Longquan celadon wares were made at Jingdezhen in the early 1700s. But outright fakes were also made using special clay. These were artificially aged by boiling them in meat broth, refiring them, and storing them in sewers. A missionary recorded that this way, the wares could be passed off as hundreds of years old.

- In the late 1800s, fakes of Kangxi-period famille noire wares were made that were good enough to fool experts. Many such pieces can still be seen in museums today. Many real Kangxi porcelain pieces also had extra famille noire enamel decoration added in the late 1800s (a process called "clobbering"). Some modern experts believe that porcelain with famille noire enamels was not made at all during the Kangxi period, though this is debated.

- A trend for Kangxi period (1661 to 1722) blue and white wares grew very popular in Europe in the late 1800s. This led to Jingdezhen making lots of porcelain that looked like older pieces. These blue and white wares were not fakes or even convincing copies. However, some pieces had four-character Kangxi reign-marks, which still cause confusion today. Kangxi reign-marks like the one shown in the picture only appear on wares made towards the end of the 1800s or later.

How to Tell if Pottery is Real

The most common test is the thermoluminescence test, or TL test. It's used on some types of ceramic to roughly guess when it was last fired. Thermoluminescence dating uses small samples of pottery drilled or cut from the piece. This can be risky and damage the piece. So, this test is rarely used for fine, high-fired ceramics. TL testing cannot be used at all on some types of ceramics, especially high-fired porcelain.

Images for kids

-

Water jar from the Neolithic period, Yangshao culture (around 5000–3000 BC)

-

White pottery pitcher from the Shandong Longshan culture, 2500–2000 BC

-

White pottery pot with geometric design, Shang dynasty (1600–1100 BC)

-

Earthenware vase, Eastern Zhou, 4th-3rd century BC, British Museum

-

A pottery bell from the Warring States period (403–221 BC)

-

A painted pottery dou vessel with a dragon design from the Warring States period (403–221 BC)

-

Soldiers from the Terracotta Army, buried by 210 BC, Qin dynasty (221–206 BC)

-

.

Yangshao culture earthenware highlighted in The Macau Museum collection in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Longshan culture steam cup highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

Ceramic statues with polychrome, from the 2nd century BC, Han dynasty.

-

An earthenware goose pourer with lacquerware paint designs, Western Han dynasty, late 3rd century BC to early 1st century AD

-

A Han celadon pot with mountain-shaped lid and animal designs

-

Western Han dynasty terracotta vases with acrobats

-

An Eastern Han glazed ceramic statue of a horse with halter and bridle headgear, late 2nd century or early 3rd century AD

-

An Eastern Han ceramic candle-holder with animal figurines

-

.

Han dynasty earthenware dancer highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Han dynasty ceramic-earthenware highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

A celadon ceramic candle holder in the shape of a crouched lion, Three Kingdoms period (220–265), made in Eastern Wu

-

A celadon hunping jar with sculpted designs of architecture, from the Jin dynasty (266–420)

-

A black-glazed wine or water jug with a rooster-headed spout, Jin dynasty (266–420)

-

A footed earthenware lamp with lions, from either the Northern Dynasties period or Sui dynasty, 6th century

-

Northern Dynasties lotus vessel

-

A ceramic cavalryman with a horn, Northern Wei (386–534)

-

Grey stoneware jar with high-fired glaze. Sui dynasty (581–618).The jar is a utilitarian object with lugs on its shoulder to secure a cloth or rattan lid.

-

.

Six Dynasties period, Western Jin dynasty stoneware sculpture highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Six Dynasties period, western Jin dynasty ceramic-stoneware incense burner highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

A Sogdian man of the Western Regions riding a Bactrian Camel, a sancai glazed figurine from the Tang dynasty

-

.

Tang dynasty ceramic-earthenware highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Tang dynasty earthenware bird highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Tang dynasty earthenware bowl highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Tang dynasty earthenware highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

Southern Song dynasty celadon vase with dish shaped mouth, Longquan celadon

-

Celadon amphora with dragon handles

-

Celadon vase from the Khitan-led Liao dynasty (907–1125 AD)

-

Northern Song dynasty white-glazed baby boy pillow

-

A glazed stoneware pillow from the Song dynasty, Cizhou ware

-

Glazed pottery building, Northern Song dynasty

-

Glazed pottery pagoda, Northern Song dynasty

-

Porcelain pillow Jin dynasty (1115–1234), Cizhou ware

-

.

Northern Song dynasty stoneware dish highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Northern Song dynasty stoneware dish highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Northern song dynasty stoneware bowl highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Song dynasty stoneware cosmetics box highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

Celadon shoulder pot, late Yuan dynasty, with relief peaches, lotuses, peonies, willows, and palms

-

Sancai-glazed Chinese ceramic incense burner, Yuan dynasty

-

Guanyin statuette, Yuan dynasty

-

Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy) with children, statuette made of Dehua porcelain ware

-

Dish, Yongle reign (1403–1424), porcelain with underglaze blue

-

Porcelain vase from the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (1521–1567)

-

A Ming glazed earthenware statue of a seated Buddha

-

"Monk's cap ewer" with "secret" inscription (an hua) in Sanscrit; this shape was for use on altars, normally in white, and often presented to Buddhist shrines by the emperor

-

Wanli period covered jar in green and yellow

-

.

Ming dynasty ceramic-porcelain bottle highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Ming dynasty export porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Ming dynasty porcelain jar in The Macau Museum collection in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Ming dynasty porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

Famille rose plate from a famous set made for the 60th birthday of the Kangxi Emperor in 1713

-

Vase, Kangxi reign (1661–1722), painted with famille jaune enamels on the biscuit and on the glaze.

-

Vase in the form of a Pomegranate, Yongzheng reign (1722–1735), "claire-de-lune glaze"

-

Famille rose dish with flowering prunus, 1723–1735

-

Copper-red porcelain from the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor (1722–1735)

-

Porcelain from the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1735–1796)

-

Porcelain plate, Qianlong Emperor (1735–1796), for export to the Dutch.

-

Snuff bottle, 9.9 cm tall, Qianlong reign

-

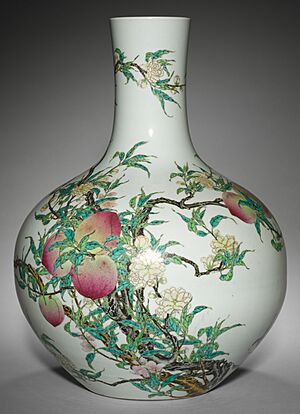

Famille rose vase with peaches (one of a pair), Qianlong reign

-

White porcelain from the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1735–1796)

-

Vase with famille rose enamels, Qianlong reign

-

Pair of famille rose vases with landscapes of the four seasons, 1760–1795

-

Porcelain vase decorated with flowers and birds made at Jingdezhen, Jiangxi,

-

19th century porcelain vase with cover painted with overglaze enamels from Guangdong province. This type of ware, known for its colourful decoration that covers most of the surface of the piece, was popular as an export ware

-

Blue and White Jar with Cover, 18th century, National Gallery of Art

-

.

Qing dynasty, reign of Guangxu ceramic-porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

China, Qing dynasty, reign of Xianfeng Wu Shuang Pu ceramic-porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Qing dynasty, reign of Qianlong ceramic-porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Qing dynasty, reign of Qianlong ceramic-porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal

-

.

Qing dynasty, reign of Jiaqing ceramic-porcelain highlighted in The Macau Museum in Lisbon, Portugal