Shunzhi Emperor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shunzhi Emperor順治帝 |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 8 October 1643 – 5 February 1661 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Hong Taiji | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Kangxi Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Regents | Dorgon (1643–1650) Jirgalang (1643–1647) |

||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1644–1661 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Chongzhen Emperor (Ming dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Kangxi Emperor (Qing dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Aisin Gioro Fulin (愛新覺羅·福臨) 15 March 1638 (崇德三年 正月 三十日) Yongfu Palace, Mukden Palace |

||||||||||||||||

| Died | 5 February 1661 (aged 22) (順治十八年 正月 七日) Hall of Mental Cultivation |

||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Xiao Mausoleum, Eastern Qing tombs | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts |

Consort Jing

(m. 1651; dep. 1653)Empress Xiaohuizhang

(m. 1654)Empress Xiaoxian

(m. 1656; died 1660)Empress Xiaokangzhang

(m. 1653) |

||||||||||||||||

| Issue | Fuquan, Prince Yuxian of the First Rank Kangxi Emperor Changning, Prince Gong of the First Rank Longxi, Prince Chunjing of the First Rank Princess Gongque of the Second Rank |

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| House | Aisin Gioro | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Qing | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Hong Taiji | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiaozhuangwen | ||||||||||||||||

| Shunzhi Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 順治帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 顺治帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Smoothly-Ruling Emperor" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

The Shunzhi Emperor (born Fulin, 15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661) was an important emperor of the Qing dynasty in China. He was the second Qing emperor and the first to rule over all of China proper. He reigned from 1644 to 1661.

Fulin became emperor in September 1643 when he was only five years old. A group of Manchu princes chose him after his father, Hong Taiji, passed away. They also appointed two powerful regents to help him rule: Dorgon and Jirgalang. Both were members of the Aisin Gioro royal family.

From 1643 to 1650, Dorgon held most of the power. Under his leadership, the Qing Empire took over most of the land from the fallen Ming dynasty. They chased away Ming supporters and set up Qing rule across China. Some of Dorgon's rules, like forcing people to shave their foreheads and wear a queue (a braided ponytail), were very unpopular.

After Dorgon died in late 1650, the young Shunzhi Emperor began to rule by himself. He tried to stop corruption and reduce the power of the Manchu nobles. In the 1650s, Ming loyalists fought back, but by 1661, the Qing armies had defeated their main enemies. These included the seafarer Koxinga and the Prince of Gui from the Southern Ming dynasty.

The Shunzhi Emperor died at just 22 years old from smallpox. This was a very contagious disease common in China, but the Manchus had no natural protection against it. His third son, Xuanye, became the next emperor. Xuanye had already survived smallpox, which was a key reason he was chosen. He would rule for sixty years as the Kangxi Emperor.

Not many records from the Shunzhi era have survived. This makes it a less known period in Qing history. The name "Shunzhi" was the name of his reign period in Chinese. This title also had Manchu and Mongolian versions. His personal name was Fulin, and his posthumous name was Shizu.

Contents

The Qing Dynasty's Rise to Power

In the 1580s, during the Ming dynasty, many Jurchen tribes lived in Manchuria. A leader named Nurhaci (1559–1626) united most of these tribes. He created a military and social system called the Eight Banners. These banners were groups of soldiers and their families, organized by color. Nurhaci gave control of these banners to his sons and grandsons.

Around 1612, Nurhaci changed his clan's name to Aisin Gioro. This name meant "golden Gioro" in the Manchu language. It also honored an older "golden" dynasty founded by Jurchens. In 1616, Nurhaci declared his independence from the Ming by starting the "Later Jin" dynasty. He then captured many important cities from the Ming. Nurhaci died in 1626 after being wounded in battle.

Nurhaci's son, Hong Taiji, continued to build the new state. He made his own power stronger and copied Chinese government systems. He also added Mongol allies and Chinese soldiers to the Eight Banners. In 1629, he attacked near Beijing and captured Chinese craftsmen. These craftsmen knew how to make Portuguese cannon.

In 1635, Hong Taiji renamed the Jurchens the "Manchus." In 1636, he changed the name of his dynasty from "Later Jin" to "Qing." By 1643, the Qing were ready to attack the Ming dynasty. The Ming was struggling with money problems, diseases, and large rebellions caused by hunger.

Becoming Emperor: Fulin's Rise

When Hong Taiji died in September 1643, he had not chosen who would rule next. This caused a big problem for the young Qing state. Several powerful princes wanted to become emperor. These included Nurhaci's sons Daišan, Dorgon, and Dodo, and Hong Taiji's son Hooge.

The decision was made by the Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers. This was the main decision-making group for the Manchus. Many princes thought Dorgon, a skilled military leader, should be emperor. But Dorgon said that one of Hong Taiji's sons should take the throne.

To respect Dorgon's power but keep the throne in Hong Taiji's family, the council chose Fulin. He was Hong Taiji's ninth son. They decided that Dorgon and Jirgalang would be the five-year-old Fulin's regents. Fulin was officially crowned emperor of the Qing dynasty on 8 October 1643. His reign was named "Shunzhi."

Dorgon's Regency: Ruling for the Young Emperor (1643–1650)

In February 1644, Jirgalang gave control of all state matters to Dorgon. Dorgon was a strong leader, and by June 1644, he was firmly in charge of the Qing government and its army.

The Qing Take Beijing

In early 1644, peasant rebellions were getting close to Beijing, the Ming capital. On 24 April, a rebel leader named Li Zicheng broke into the city. The Chongzhen Emperor of the Ming dynasty took his own life.

When Dorgon heard this, his Chinese advisors told him to act. They suggested he present the Qing as avengers of the Ming and claim the right to rule China. The last obstacle was Ming general Wu Sangui, who was guarding Shanhai Pass. Wu Sangui was caught between the Manchus and Li Zicheng's rebels. He asked Dorgon for help. Dorgon agreed, but only if Wu Sangui would join the Qing. Wu Sangui had no choice but to accept.

With Wu Sangui's help, the Qing won a major victory against Li Zicheng at the Battle of Shanhai Pass on 27 May. Li's defeated troops looted Beijing for days before he left the capital.

Setting Up the New Capital

On 5 June, the people of Beijing welcomed their new rulers. They were surprised to see Dorgon, a Manchu prince, present himself as the Regent. Dorgon set up his base in the Wuying Palace, one of the few buildings left after Li Zicheng burned the palace. Qing soldiers were ordered not to loot, which made the change to Qing rule quite smooth. However, Dorgon also ordered that all people claiming to be Ming emperors be executed.

On 7 June, Dorgon announced that officials could keep their jobs if people shaved their foreheads and wore a queue. But he had to cancel this rule three weeks later because it caused rebellions around Beijing.

The Shunzhi Emperor arrived in Beijing on 19 October 1644. On 30 October, the six-year-old emperor performed important sacrifices at the Temple of Heaven. This ceremony showed that the Qing dynasty now held the "Mandate of Heaven," meaning they had the right to rule. Fulin was formally enthroned on 8 November. Dorgon's title was raised to "Uncle Prince Regent," showing his very high status.

One of Dorgon's first orders was to give the northern part of Beijing to the Eight Banners soldiers. This included Chinese soldiers who had joined the Banners. Farmland outside the capital was also given to Qing troops. Former landowners became tenants, paying rent to their new Manchu landlords. This caused problems for many years.

In 1646, Dorgon brought back the civil service examinations. These tests were used to choose government officials. They were held every three years, just like under the Ming. The exams asked how Manchus and Chinese could work together. To encourage harmony, Dorgon allowed Chinese men to marry Manchu women in 1648.

Conquering All of China

Under Dorgon's leadership, the Qing conquered almost all of China. They pushed the remaining Ming loyalists to the far southwest. After putting down revolts in northern China, Dorgon sent armies to defeat Li Zicheng in Xi'an. Li was killed in September 1645.

In April 1645, the Qing attacked the rich Jiangnan region south of the Yangtze River. A Ming prince had set up a loyalist government there. The Ming forces were weak and divided. Qing armies swept south, capturing key cities. Yangzhou bravely resisted but fell on 20 May. Dorgon's brother, Prince Dodo, then ordered a terrible slaughter of the city's people. This act of terror made other cities surrender quickly. Nanjing surrendered without a fight. By July 1645, the Qing controlled the main cities of Jiangnan.

On 21 July 1645, Dorgon issued a very unpopular order. All Chinese men had to shave their foreheads and braid their hair into a queue, like the Manchus. Refusal meant death. This rule caused widespread resistance. The people of Jiading and Songjiang were massacred for resisting. Jiangyin also fought for 83 days. When it fell, the Qing army killed tens of thousands of people. These massacres ended armed resistance in the Lower Yangtze region.

After Nanjing fell, two more Ming princes tried to set up new governments. But they failed to work together. In 1646, Qing armies attacked, capturing and executing the "Longwu Emperor." His adopted son, Koxinga, fled to Taiwan.

In late 1646, two more Southern Ming rulers appeared in Guangzhou. They even bought robes from theater groups because they lacked official costumes. These two Ming groups fought each other. In January 1647, a small Qing force captured Guangzhou, killing one emperor and forcing the other to flee.

However, in May 1648, a former Ming general rebelled against the Qing. This helped the Ming loyalists retake much of southern China. But new Qing armies soon reconquered these areas. On 24 November 1650, Qing forces led by Shang Kexi captured Guangzhou again and massacred up to 70,000 people.

Meanwhile, Qing armies also defeated a bandit leader named Zhang Xianzhong in Sichuan in 1647. Further north, Muslim leaders revolted in Gansu province, claiming they wanted to restore the Ming. These rebels were crushed by 1650.

Shunzhi's Personal Rule (1651–1661)

Taking Control from Dorgon's Supporters

Dorgon's sudden death on 31 December 1650 led to big changes. At first, Dorgon was given an imperial funeral. But soon, his supporters were arrested. Jirgalang, who had lost his regent title earlier, gained support from other Manchu officers.

Jirgalang helped the young Shunzhi Emperor take full power. On 1 February 1651, Jirgalang announced that the Shunzhi Emperor, almost thirteen, would now rule on his own. The regency officially ended. Jirgalang then accused Dorgon of trying to take too much power. Dorgon's honors were removed, and his former supporters were removed from government.

Fighting Corruption and Factionalism

On 7 April 1651, the Shunzhi Emperor declared he would fight corruption. This led to conflicts among officials. He dismissed a powerful northern Chinese official and replaced him with Chen Mingxia, a southern Chinese official. Chen became a close advisor to the emperor. However, Chen was later accused of corruption and other crimes. He was executed in April 1654.

In November 1657, a major cheating scandal happened during the imperial exams in Beijing. Candidates from Jiangnan had bribed examiners. Seven supervisors were executed, and hundreds of others were punished. This scandal showed how much corruption was in the government.

Adopting Chinese Ways of Ruling

The Shunzhi Emperor encouraged Chinese people to join the government. He brought back many Chinese-style institutions that Dorgon had changed. He studied history and Chinese classics with scholars. He also surrounded himself with new advisors who knew Chinese well.

In 1652, he issued the "Six Edicts." These were basic Confucian rules telling people to be respectful and follow laws. He also brought back the Hanlin Academy and the Grand Secretariat in 1658. These institutions were based on Ming models. They gave Chinese officials more power and reduced the influence of the Manchu elite.

To balance the power of the Manchu nobility, the emperor created the Thirteen Offices in July 1653. These offices were run by Chinese eunuchs rather than Manchu servants. Eunuchs had been kept under strict control before. But the young emperor used them to counter the power of his mother and former regent Jirgalang. By the late 1650s, eunuchs became very powerful. They handled money, advised on appointments, and even wrote imperial orders. This worried many officials, who feared a return to the problems of eunuch power seen in the late Ming dynasty. The emperor's favorite eunuch, Wu Liangfu, was caught in a corruption scandal in 1658. The Thirteen Offices would be removed after the Shunzhi Emperor's death.

Relations with Other Regions

In 1646, Qing armies found envoys from the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Annam, and the Spanish in Manila. These groups had come to pay tribute to the fallen Ming emperor. The Qing sent them home with instructions to submit to the Qing. The Ryūkyū Islands sent their first tribute to the Qing in 1649, Siam in 1652, and Annam in 1661.

In 1646, a Moghul prince from Turpan also sent an embassy. He wanted to restart trade with China. The Qing agreed, allowing trade in Beijing and Lanzhou. However, this was stopped by a Muslim rebellion in the northwest. Trade with Hami and Turfan restarted in 1656.

In 1651, the emperor invited the 5th Dalai Lama, the leader of Tibetan Buddhism, to Beijing. Qing emperors had supported Tibetan Buddhism for a long time. But there were also political reasons for the invitation. Tibet was becoming powerful, and the Dalai Lama influenced Mongol tribes. To prepare, the Shunzhi Emperor ordered the building of the White Dagoba in Beihai Park. The Dalai Lama arrived in Beijing in January 1653.

Meanwhile, Russian explorers like Vassili Poyarkov and Yerofey Khabarov explored the Amur River valley. They tried to collect fur tribute from local people, but these groups already paid tribute to the Shunzhi Emperor. In 1654, the Russians defeated a small Manchu force. But in 1658, Manchu general Šarhūda attacked the Russians with a large fleet. This Qing victory temporarily cleared the Amur valley. However, conflicts between Russia and the Qing continued until 1689.

Continuing Campaigns Against Ming Loyalists

Even though the Qing had pushed the Southern Ming far south, Ming loyalists were still fighting. In August 1652, Li Dingguo, a general protecting the Yongli Emperor, recaptured Guilin. Many commanders who had supported the Qing switched back to the Ming side.

In 1653, the Qing court put Hong Chengchou in charge of retaking the southwest. He slowly built up his forces. In late 1658, Qing troops launched a major campaign into Guizhou and Yunnan. In January 1659, a Qing army took the capital of Yunnan. This forced the Yongli Emperor to flee into Burma. He stayed there until 1662, when he was captured and executed by Wu Sangui.

Zheng Chenggong ("Koxinga") also continued to fight for the Southern Ming. In 1659, he sailed up the Yangtze River with his fleet. He took several cities and even threatened Nanjing. The emperor was very angry when he heard this. But the siege of Nanjing was broken, and Zheng Chenggong was forced back to Fujian. Under pressure from Qing fleets, Zheng fled to Taiwan in April 1661. His descendants continued to resist Qing rule until 1683.

Personality and Relationships

After Fulin began to rule on his own in 1651, his mother, the Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, arranged for him to marry her niece. But the young emperor removed his first Empress in 1653. The next year, Xiaozhuang arranged another marriage with her family. Fulin also disliked his second empress, but he was not allowed to demote her. She never had children.

Starting in 1656, the Shunzhi Emperor showed great affection for Consort Donggo. She gave birth to his fourth son in November 1657. The emperor wanted this son to be his heir, but the child died early in 1658.

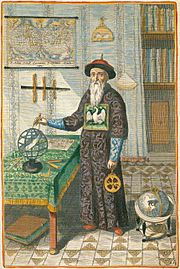

The Shunzhi Emperor was open-minded. He often sought advice from Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a Jesuit missionary from Germany. Schall advised him on many topics, including astronomy and government. The emperor called Schall "grandfather" (mafa in Manchu). Schall reported that the emperor often visited his house and talked late into the night. The emperor even allowed Schall to adopt a son. However, the Jesuits' hope of converting the emperor to Christianity ended when he became a strong follower of Chan Buddhism in 1657.

The emperor learned Chinese very well. This allowed him to manage state affairs and enjoy Chinese arts like calligraphy and drama. He was very emotional and cared deeply about love. He could even recite long parts of the popular play Romance of the Western Chamber.

Death and Succession

In September 1660, Consort Donggo, the emperor's favorite consort, died suddenly. She was overcome with grief after losing her child. The emperor was deeply saddened for months. Then, on 2 February 1661, he caught smallpox.

On 4 February 1661, officials were called to his bedside to record his last wishes. On the same day, his seven-year-old third son, Xuanye, was chosen as his successor. Xuanye was likely chosen because he had already survived smallpox. The emperor died on 5 February 1661 in the Forbidden City, at the age of twenty-two.

The Manchus feared smallpox greatly because they had no natural protection against it. They often died if they caught it. They had agencies to find smallpox cases and isolate sick people. During outbreaks, royal family members were sent to "smallpox avoidance centers." The Shunzhi Emperor was especially afraid of the disease. Despite precautions, he still died from it.

The Forged Last Will

The emperor's last will was made public on the evening of 5 February. It named four regents for his young son: Oboi, Soni, Suksaha, and Ebilun. These men had helped remove Dorgon's supporters earlier.

Historians believe that the emperor's will was changed or even completely made up by these regents and Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang. The will said the emperor regretted his Chinese-style ruling, his reliance on eunuchs, and his favoritism toward Chinese officials. It also said he regretted neglecting Manchu nobles and traditions. These regrets were very different from how he had actually ruled. The forged will gave great power to the four regents. It supported their pro-Manchu policies during the period known as the Oboi regency, which lasted from 1661 to 1669.

After His Death

Because the cause of the emperor's death was not clearly announced, rumors spread. Some said he had not died but had become a monk in a Buddhist monastery. This seemed believable because he had become a strong follower of Chan Buddhism in the late 1650s. However, most evidence suggests he did die.

After 27 days of mourning, the emperor's body was moved on 3 March 1661. Many valuable items were burned as funeral offerings. Two years later, in 1663, his body was buried. Unlike Manchu custom, he was not cremated. He was buried in the Eastern Qing Tombs, northeast of Beijing. His tomb was the first in that area.

Shunzhi's Legacy

The fake will, which claimed the Shunzhi Emperor regretted abandoning Manchu traditions, gave power to the pro-Manchu policies of the Kangxi Emperor's four regents. The regents quickly closed the Thirteen Eunuch Bureaus. They increased the power of the Imperial Household Department, which was run by Manchus. They also limited membership in the Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers to Manchus and Mongols.

The regents also took harsh actions against Chinese subjects. They executed many people in the wealthy Jiangnan region for criticizing the government and for not paying taxes. They also forced people living along the coast to move inland. This was to starve the Kingdom of Tungning on Taiwan, which was run by Koxinga's descendants.

After the Kangxi Emperor took full power in 1669, he changed many of the regents' policies. He brought back institutions his father had liked, such as the Grand Secretariat. This gave Chinese officials an important role in government. He also defeated the rebellion of the Three Feudatories. These were three Chinese military commanders who had helped the Qing conquer China but had become very powerful rulers in the south.

The civil war (1673–1681) tested the loyalty of the new Qing subjects, but the Qing armies won. After the victory, a special examination was held in 1679 to attract Chinese scholars who had refused to serve the new dynasty. These scholars were assigned to write the official history of the fallen Ming dynasty. The rebellion was defeated in 1681. In the same year, the Kangxi Emperor began using variolation to protect royal children from smallpox. When the Kingdom of Tungning fell in 1683, the Qing dynasty's military control was complete.

The strong foundation built by Dorgon, and the Shunzhi and Kangxi emperors, allowed the Qing to become a very successful empire. However, the long period of peace that followed made the Qing unprepared for the powerful European nations with modern weapons that arrived in the 1800s.

Family Life

The Shunzhi Emperor had at least thirty-two spouses, though only nineteen are officially recorded. Twelve of them had children with him. He had two empresses during his reign, both related to his mother.

He had a total of fourteen children, but only four sons and one daughter lived to adulthood. Unlike later Qing emperors, his sons' names did not include a special generational character.

Empresses

- Consort Jing, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (靜妃 博爾濟吉特氏), his first cousin.

- Empress Xiaohuizhang, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (孝惠章皇后 博爾濟吉特氏; 1641 – 1718), his grand-niece.

- Empress Xiaoxian, of the Donggo clan (孝獻皇后 董鄂氏; 1639 – 1660).

- Prince Rong of the First Rank (榮親王; 1657 – 1658), his fourth son.

- Empress Xiaokangzhang, of the Tunggiya clan (孝康章皇后 佟佳氏; 1638 – 1663).

- Xuanye, the Kangxi Emperor (聖祖 玄燁; 1654 – 1722), his third son.

Consorts

- Consort Dao, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (悼妃 博爾濟吉特氏; died 1658), his first cousin.

- Consort Zhen, of the Donggo clan (貞妃 董鄂氏; died 1661).

- Consort Ke, of the Shi clan (恪妃 石氏; died 1668).

- Consort Gongjing, of the Hotsit Borjigit clan (恭靖妃 博爾濟吉特氏; died 1689).

- Consort Shuhui, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (淑惠妃 博爾濟吉特氏; 1642 – 1713), his first cousin once removed.

- Consort Duanshun, of the Abaga Borjigit clan (端順妃 博爾濟吉特氏; died 1709).

- Consort Ningque, of the Donggo clan (寧愨妃 董鄂氏; died 1694).

- Fuquan, Prince Yuxian of the First Rank (裕憲親王 福全; 1653 – 1703), his second son.

Concubines

- Mistress, of the Ba clan (巴氏)

- Niuniu (牛鈕; 1651 – 1652), his first son.

- Third daughter (1654 – 1658).

- Fifth daughter (1655 – 1661).

- Mistress, of the Chen clan (陳氏; died 1690)

- First daughter (1652 – 1653).

- Changning, Prince Gong of the First Rank (恭親王 常寧; 1657 – 1703), his fifth son.

- Mistress, of the Yang clan (楊氏)

- Princess Gongque of the Second Rank (和碩恭愨公主; 1654 – 1685), his second daughter.

- Married Na'erdu (訥爾杜; died 1676) of the Manchu Gūwalgiya clan in 1667.

- Fourth daughter (1655 – 1661).

- Princess Gongque of the Second Rank (和碩恭愨公主; 1654 – 1685), his second daughter.

- Mistress, of the Nara clan (那拉氏)

- Sixth daughter (1657 – 1661).

- Mistress, of the Tang clan (唐氏)

- Qishou (奇授; 1660 – 1665), his sixth son.

- Mistress, of the Niu clan (鈕氏)

- Longxi, Prince Chunjing of the First Rank (純靖親王 隆禧; 1660 – 1679), his seventh son.

- Mistress, of the Muktu clan (穆克圖氏)

- Yonggan (永幹; 1661 – 1668), his eighth son.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Shunzhi para niños

In Spanish: Shunzhi para niños

- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

- Chronology of the Shunzhi reign

- List of emperors of the Qing dynasty