Imperial examination facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Imperial examination |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

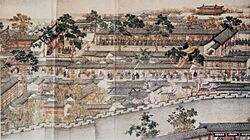

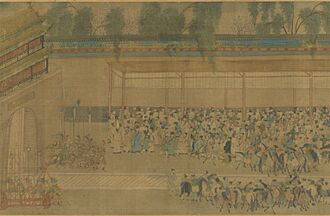

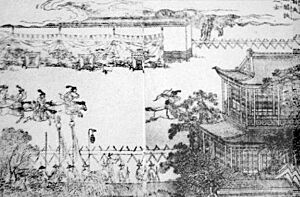

Imperial examination candidates gathering around the wall where results were posted, an announcement known as 'releasing the roll' (放榜; fàngbǎng) – by Qiu Ying (c. 1540)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 科舉 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 科举 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | kējǔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | subject recommendation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 과거 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 科擧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 科擧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 科挙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡤᡳᡡ ᡰ᠊ᡳᠨ ᠰᡳᠮᠨᡝᡵᡝ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Möllendorff | giū žin simnere | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The imperial examination was a special test system in ancient China. It was used to pick people for government jobs. Instead of choosing officials based on their family or wealth, these exams aimed to find the smartest and most talented individuals.

This idea of choosing people based on skill started very early in Chinese history. But using written tests seriously began during the Sui dynasty (581–618). It grew even more important in the Tang dynasty (618–907). The system became super important during the Song dynasty (960–1279). It lasted for almost 1,000 years until it was stopped in 1905, during the late Qing dynasty. Today, similar tests are still used to get government jobs in China and Taiwan.

These exams made sure that government officials all knew the same things. They studied Chinese classics, writing, and literature. This shared knowledge helped keep the huge empire united. The idea that anyone could succeed through hard work also made people trust the emperor's rule. The exam system also helped reduce the power of rich families and military leaders. It helped a new group of educated officials, called scholar-bureaucrats, rise to power.

From the Song dynasty onwards, the exams became very organized. There were three main levels: local, provincial, and national (court). During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the tests focused mainly on Neo-Confucian ideas. The highest degree, called jinshi, was needed for the most important jobs. However, many people passed the basic shengyuan degree but couldn't get a job. By the 19th century, rich families could sometimes buy their sons a way into the system. Some people in the late 1800s thought the exams stopped new ideas in science and technology. They wanted changes. Only about 1% of the millions of people who took the exams each year actually passed.

The Chinese exam system greatly influenced how other countries chose their government workers. Countries like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam used similar systems. European explorers and diplomats also learned about the Chinese exams. This encouraged countries like France, Germany, and Britain to use similar tests. The British government started using a testing system for civil servants in 1855. The United States also began using such programs for some government jobs after 1883.

Contents

History of the Imperial Examinations

Early Exam Ideas

Tests of skill, like archery contests, have been around since the Zhou dynasty. The focus on Confucian teachings in later exams came largely from Emperor Wu of Han during the Han dynasty. Some exams existed from the Han to the Sui dynasty. But they weren't the main way to get government jobs. Most jobs were given based on recommendations, social status, and moral character.

The idea of bureaucratic imperial exams began in 605 during the short Sui dynasty. The next dynasty, the Tang dynasty, used these exams on a small scale. But the system grew much bigger under Wu Zetian, who ruled the Wu Zhou dynasty. She even added a military exam. However, military exams never became as important as the civil ones.

In the early Han dynasty, top jobs were mostly held by rich, noble families. In 165 BC, Emperor Wen of Han introduced exams for government jobs. But these early exams didn't focus much on Confucian ideas. Later, Emperor Wu of Han created special academic positions in 136 BC. He also started the Taixue (Imperial University) and the imperial exam system. Officials would choose candidates to take an exam on Confucian classics. Emperor Wu would then pick officials from those who passed.

This system relied heavily on families who could afford education. Before paper and printing were common, books were expensive. So, only a few could get enough education for government service. Also, high-ranking officials could recommend their family members. This meant relatives of powerful officials had a better chance of getting jobs.

During the Three Kingdoms period, the first standardized way to recruit officials was introduced. It was called the nine-rank system. Each job was given a rank from one to nine. Officials judged candidates based on their morals and social status. This system meant that powerful families usually got all the high-ranking jobs. People from poorer families filled the lower ranks.

Tang Dynasty Exams

The Tang dynasty and the rule of Empress Wu made the exams much bigger. They went beyond just simple policy questions and interviews. Oral interviews were supposed to be fair. But in reality, they often favored candidates from powerful families in the capital cities.

Under the Tang, there were six main types of civil service exams. These included tests for cultivated talents, classicists, presented scholars, legal experts, writing experts, and math experts. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang also added categories for Daoism and apprentices. The hardest exam, the jinshi degree, became the most important over time. By the late Tang, a jinshi degree was needed for high-ranking jobs. Even people recommended for jobs had to take exams.

The exams were held in the first month of the year. After grading, the results were sent to the Grand Chancellor, who could change them. The emperor could also order a re-exam. The results were then published in the second month.

Classicists were tested by completing phrases from classic texts. If they answered five out of ten questions correctly, they passed. This was seen as easy. The jinshi exam was much harder. It tested Confucian classics, history, official document writing, and poetry. Because so few people passed the jinshi exam, those who did gained great social standing.

Candidates who passed the exam didn't automatically get a job. They still had to pass a quality review by the Ministry of Rites. After that, they could wear official robes.

Wu Zetian's rule was a key moment for the exam system. Before her, Tang rulers were all male members of the Li family. Wu Zetian, who became emperor in 690, was a woman outside this family. She needed a new way to gain power. Reforming the imperial exams was a big part of her plan. She wanted to create a new group of elite officials from more humble backgrounds. Both the palace and military exams were started under Wu Zetian.

From 702 onwards, examinees' names were hidden to prevent examiners from knowing who wrote the papers. Before this, candidates would even show their literary works to examiners to impress them.

Song Dynasty Exams

In the Song dynasty, the imperial exams became the main way to get official jobs. More than a hundred palace exams were held, giving out many jinshi degrees. The exams were open to adult Chinese men, with some rules. This even included people from areas controlled by other dynasties. Records show 70,000-80,000 examinees in 1088. By the mid-13th century, over 400,000 people registered for local exams each year. The number of active jinshi degree holders ranged from 5,000 to 10,000. The Song government gave out more than twice the number of degrees compared to the Tang dynasty. On average, 200 or more degrees were given each year.

The exam system had three levels: prefectural, metropolitan, and palace exams. The prefectural exam was held on the 15th day of the eighth month. Those who passed went to the capital for the metropolitan exam in Spring. Metropolitan exam graduates then went to the palace exam.

Many people from lower social classes became important officials by doing well in the exams. Studies show that about 57% of degree holders in 1148 and 1256 came from families where their father, grandfather, or great-grandfather had not been an official. However, most did have some relative in the government. Famous officials who passed the exams include Wang Anshi and Zhu Xi. Studying for the exams took a lot of time and money. Most candidates came from the wealthy land-owning scholar-official class.

From 937, the emperor himself supervised the palace exam. In 992, papers were submitted anonymously to prevent examiners from knowing the candidate's identity. This practice spread to other exams later. From 1037, examiners couldn't supervise exams in their home area. Examiners and high officials were also forbidden from contacting each other before exams. Papers were recopied to hide the candidate's handwriting.

In 1009, Emperor Zhenzong of Song set limits on the number of degrees given. In 1090, only 40 degrees were given to 3,000 candidates in Fuzhou. This meant only one degree for every 75 candidates. By the 13th century, only 1% of candidates passed the prefectural exam. Even the lowest-level exam graduates were considered elite.

Many reforms were tried during the Song dynasty. Wang Anshi and Zhu Xi successfully argued that poems should be removed from exams. They believed poems were not useful for government work. The poetry section was removed in the 1060s.

Yuan Dynasty Exams

Imperial exams stopped for a while after Kublai Khan and his Yuan dynasty defeated the Song in 1279. Kublai believed Confucian learning wasn't needed for government jobs. He also didn't want to rely on Chinese language and scholars. He wanted to appoint his own people. Stopping the exams made traditional learning less respected. It also encouraged new types of writing not focused on exam success.

The exam system was brought back in 1315 by Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan. The new system had big changes. It divided examinees into regional groups that favored Mongols. It put Southern Chinese at a big disadvantage. There were limits on the number of candidates and degrees given. These limits were based on four groups: Mongols, their non-Han allies, Northern Chinese, and Southern Chinese. Exams were written in Chinese and based on Confucian texts. But Mongols and their allies got easier questions.

Under this new system, about 21 degrees were given each year. The way the groups were divided favored Mongols and Northern Chinese. This was true even though Southern Chinese were the largest part of the population.

Ming Dynasty Exams

The Ming dynasty kept and expanded the exam system. The Hongwu Emperor first didn't want to restart the exams. He thought they didn't teach practical knowledge. In 1370, he said exams would follow the Neo-Confucian teachings of Zhu Xi. But he stopped the exams two years later, preferring appointments by referral. In 1384, exams were brought back. Hongwu added a new part to the exams five days after the first. These new exams focused on practical learning. This included law, math, calligraphy, horse riding, and archery. The emperor really wanted archery included.

Provincial and metropolitan exams had three parts. The first part had questions on the Four Books and Classics. The second part had essays and official document writing. The third part had essays on Classics, history, and current events. The palace exam was just one part, with questions on important matters or current affairs. Answers had to follow a specific structure called the eight-legged essay. This essay had eight parts and was 550-700 characters long. Some scholars, like Gu Yanwu, thought the eight-legged essay was very bad.

The Hanlin Academy was very important for exam graduates in the Ming dynasty. Top metropolitan exam graduates were directly appointed to the Hanlin Academy. Regular graduates became junior compilers or editors. After 1458, only jinshi graduates could get jobs in the Hanlin Academy and Grand Secretariat. Many top government jobs were also only for jinshi graduates. Ninety percent of Grand Chancellors during the Ming dynasty were jinshi degree holders.

The Neo-Confucian ideas became the main guide for scholars. This limited how they could understand Confucian texts. At the same time, more people and more trade led to a huge increase in lower-level degree candidates. The Ming government didn't increase the number of degrees given. By 1600, there were about 500,000 shengyuan in a population of 150 million. This meant one shengyuan for every 300 people. This trend continued into the Qing dynasty. By the mid-19th century, it was one shengyuan for every thousand people. Getting a government job became very hard. Higher jobs were still held by jinshi degree-holders, often from elite families.

Qing Dynasty Exams

Hong Taiji, the first emperor of the Qing dynasty, wanted to use exams to create Manchu officials who were both good at fighting and educated. He started the first exam for Manchu soldiers in 1638. But Manchu soldiers didn't have time or money to prepare. So, the dynasty relied on both Manchu and Han Chinese officials chosen through the system from the Ming dynasty. During the Qing dynasty, 26,747 jinshi degrees were earned in 112 exams. This was an average of 238.8 jinshi degrees per exam.

There were also quotas (limits) on the number of graduates allowed based on their ethnic group. In the early Qing, a 4:6 Manchu to Han quota was used for the palace exam. Separate exams were held for Manchu soldiers. Later, Manchus and Mongols were encouraged to take exams in Classical Chinese. The translation exam was stopped in 1840 because too few people took it. After 1723, Han Chinese palace exam graduates had to learn the Manchu language. Being able to speak both Chinese and Manchu was favored for government jobs.

The imperial exams were not free of corruption. For example, in 1711, there were protests in Yangzhou. Students who failed accused officials of taking bribes from rich salt merchant families. Thousands of candidates protested. A long investigation found the chief examiner and successful candidates guilty. They were put to death.

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (1851–1864)

The Chinese Christian Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was a rebellion against the Qing dynasty. It was led by Hong Xiuquan, who had failed the imperial exams. The Taipings held their own exams starting in 1851. They replaced Confucian Classics with the Taiping Bible. Candidates had to write eight-legged essays using Bible quotes.

In 1853, for the first time in Chinese history, women could take the exams. Fu Shanxiang took the exam and became the first (and last) female zhuangyuan (top scholar).

End of the Exam System

By the 1830s and 1840s, officials started suggesting reforms to include Western technology in the exams. In 1864, Li Hongzhang proposed adding Western technology as a new subject. Other officials also suggested adding math and science. They also wanted to stop the military exams, which were based on old weapons like archery. In 1888, international trade was added to the imperial exams.

After military defeats in the 1890s, reformers like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao called for the exams to be stopped. The Hundred Days' Reform in 1898 suggested modernizing the system. After the Boxer Rebellion, the government planned reforms called New Policies. On September 2, 1905, the emperor ordered the exam system to be stopped. The new system created modern degrees that were similar to the old ones.

Older students who had failed to even become shengyuan were hit hard. They couldn't easily learn new things, were too proud to become merchants, and too weak for physical work.

Impact of the Exams

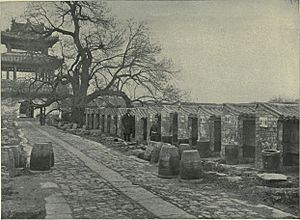

|

|

| Left: Gate of the Guozijian in Beijing, 1871. Right: The gate in 2009. | |

From Nobles to Scholars

The main goal of the imperial exams in the Sui dynasty was to weaken the power of noble families. It also aimed to give more power to the emperor. Before the Sui dynasty, noble families had a lot of control. They limited the emperor's power, especially in choosing officials. The Sui emperor created the exams to get around these powerful families. This was the start of the Chinese exam system.

The Tang dynasty built on this system. The emperor gave important government jobs to jinshi graduates. These new officials often clashed with the old noble families. By the time of Emperor Xianzong of Tang, three-fifths of the Grand Chancellors were jinshi. This change really hurt the nobles' power. But they didn't give up. They started taking the exams themselves to keep their influence. By the end of the dynasty, noble families had produced many jinshi. So, they still had a lot of influence.

Also, the number of graduates was small. They formed their own groups in the government. This was another problem for the emperor. But this problem was greatly reduced during the Song dynasty. The Song dynasty had a strong economy, which allowed more people to take and pass the exams. Since most top jobs in the Song dynasty were held by jinshi, there was less conflict between different groups. Efforts were made to stop examiners and examinees from forming special groups. While the influence of some scholar officials never disappeared, they no longer controlled how people were organized.

The scholar-bureaucrats, later called Mandarins in the West, continued to be very powerful. Their relationship with the emperor was important. As one official said in the 1040s, "The empire cannot be ruled by Your Majesty alone; the empire can only be governed by Your Majesty collaborating with the officials."

Military Under Civil Control

Even though there was a military version of the exam, the government didn't focus on it. The importance of the regular imperial exams meant that the military was controlled by the civil government. By the Song dynasty, the two highest military jobs were only for civil servants. It became normal for civil officials to be appointed as army commanders. The highest rank for a dedicated military career was reduced to unit commander. To further reduce military leaders' power, they were often moved to new positions after a campaign. This stopped commanders and soldiers from forming strong, lasting bonds. This policy continued in the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Successful military commanders, like Yue Fei, were sometimes mistrusted. Yue Fei was even executed by the Song government despite his success against the Jin dynasty. This policy sometimes hurt the military's performance. But it also prevented the military coups that happened in earlier dynasties.

Education and Schools

During the Tang period, students learned reading, writing, and text composition before entering state academies. As more people graduated, competition for government jobs became tougher. In the early Tang, there were few jinshi. But in the Song dynasty, there were more than the government needed. Several ideas were suggested to reduce the number of candidates and improve their quality. In 1044, the Qingli Reforms were put in place. These reforms included hiring experts to teach at government schools. They also set up schools in every region and required candidates to attend school for at least 300 days. Before these reforms, the government only supported a few schools. Some reformers helped create schools directly. The Qingli Reforms only lasted one year.

Even though the Qingli Reforms failed, the idea of a statewide education system was picked up by Wang Anshi (1021–1086). He thought exams alone weren't enough to find talent. He suggested creating new schools (shuyuan) to select officials. His goal was to replace exams entirely by choosing officials directly from school students. A new path to office, the Three Hall system, was introduced. The government expanded the Taixue (National University). They also ordered each region to give land to schools and hire teachers. In 1076, a special exam for teachers was introduced.

The new education policies sometimes faced criticism. Su Shi believed that schools were just places for students to learn how to pass the exams. Liu Ban thought that home education was enough. In 1078, a student accused teachers of being unfair. In 1112, a report criticized local schools for various problems. It said local supervisors wasted money and engaged in violence. The "eight virtues" system, which promoted students based on good behavior, was criticized for not being strict enough academically. In 1121, the local three-college system was stopped.

Schools continued to decline after the Southern Song period (1127–1279). The government didn't want to fund them because they didn't make immediate money. As a result, teaching staff were cut, and the national university shrank. After this period, the government stopped being very involved in state schools. According to complaints, schools got worse in quality. They had abuses, strange teachings, or no teaching at all. Schools in imperial China never fully recovered. For the rest of China's history, government-funded academies mainly served as preparation centers for the exams. They didn't offer real instruction. Wang's goal of replacing exams was never achieved.

Primary education was left to private schools during the Ming dynasty. Some schools were charity projects by the government. The government also funded special schools for the Eight Banners to teach the Manchu language and Chinese. These schools didn't have a standard curriculum or age for entry.

Too Many Graduates

The problem of too many graduates became very serious from the 18th century. The long period of peace in the Qing dynasty meant many candidates could study and apply for exams. Their papers were all very similar, making it hard for examiners to choose. Officials started looking for ways to eliminate candidates instead of finding the best ones. A complex set of rules for the exams was created, which made the whole system less effective.

Candidates Who Failed

Many candidates failed the exams, often many times. In the Tang period, only 1 or 2 out of 100 passed the palace exam. In the Song dynasty, about 1 out of 50 passed the metropolitan exam. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, about 1 out of 100 passed the provincial exam. For every shengyuan in the country, only one in three thousand would ever become a jinshi. While most candidates had some money, those from poor families risked everything to pass. Smart and ambitious candidates who failed repeatedly felt very angry. Their disappointment could turn into desperation, and sometimes even rebellion.

Huang Chao led a huge rebellion in the late Tang dynasty after failing the exams many times. He came from a wealthy family. He later started a secret society involved in illegal salt trading. His rebellion eventually led to the Tang dynasty's downfall. Hong Xiuquan led the Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century against the Qing dynasty. After his fourth and final attempt at the shengyuan exam, he had a mental breakdown. He had visions of heaven and believed he was part of a celestial family. Influenced by Christian missionaries, Hong declared his visions were from God and Jesus. He created the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and started a war that devastated parts of southeast China.

Pu Songling (1640–1715) failed the exam many times. He wrote stories that made fun of the system, showing the frustrations of candidates stuck in it.

Overall View of the Later System

Critics said the strict format of the "eight-legged essay" stopped original thinking. Writers made fun of the system's rigidity in novels like The Scholars. In the 20th century, the New Culture Movement blamed the exam system for China's weakness. Some people think that limiting exam topics made Chinese scholars less interested in math or science. This might have contributed to China falling behind Europe in science and economy.

However, the Confucian teachings in the exams were also compared to the classical studies in Europe. These studies helped choose "all-rounded" leaders. British and French civil service exams in the late 19th century also focused on Greek-Roman classics and general cultural studies. They also looked at personal qualities. These features were similar to the earlier Chinese model. In the British civil service, like in China, getting a job was based on a general education in ancient classics. This gave officials more respect.

In late imperial China, the exam system was the main way the government kept local leaders loyal. It helped keep China united. The exam system gave out prizes based on regional quotas. This meant officials were chosen from all over the country, in numbers that matched each province's population. People from all over China, even in less developed areas, had a chance to succeed in the exams.

The exam-based civil service helped create stability and social mobility (people moving up in society). The exams were based on Confucianism. This meant that local elites and ambitious people across China were taught similar values. Even though only a small number (about 5%) of those who took the exams passed, the hope of success kept them trying. Those who failed didn't lose their wealth or local social standing. As believers in Confucian ideas, they worked as teachers, supported arts, and managed local projects like irrigation or schools.

Taking the Exams

Who Could Take Them?

During the Tang dynasty, candidates were either recommended by their schools or had to sign up for exams in their home area. By the Song dynasty, almost all adult Chinese men could take the exams. The only real requirement was education.

However, there there were some official and unofficial rules about who could take the exams. Common people were divided into four groups: scholars, farmers, artisans, and merchants. Below them were "mean" people, like boat-people, beggars, entertainers, and slaves. "Mean" people were usually not allowed to hold government jobs or take the imperial exam. Some ethnic groups were also banned. Women were not allowed to take the exams. Butchers and sorcerers were sometimes excluded. Merchants were restricted until the Ming and Qing dynasties. Artisans were also restricted from official service during the Sui and Tang dynasties.

Besides official rules, there was also the cost. The path to a jinshi degree was long and very competitive. People who got a jinshi degree in their twenties were very lucky. The average age was in their thirties. Candidates had to study for years without stopping. Without money, studying for the exams was very hard. After studying, candidates also had to pay for travel, lodging, and gifts for examiners. A jinshi candidate needed someone in the government to support them. Banquets and entertainment also cost money. Because of these costs, the whole family often helped support a candidate.

How the Exams Worked

Each candidate arrived at the exam center with only a few things: a water pitcher, a chamber pot, bedding, food, an inkstone, ink, and brushes. Guards checked each student's identity and searched them for hidden texts, like cheat sheets. The exam room was a small, isolated cell with a makeshift bed, desk, and bench. Each examinee was given a cell number. Paper was provided by the examiners and had an official stamp. Candidates in the Ming and Qing periods could spend up to three days and two nights writing "eight-legged essays." Talking to others or leaving the cell was not allowed during the exam. If a candidate died, officials wrapped their body in a mat and threw it over the high walls.

To prevent cheating, officials erased any information about the candidate from the paper. They then assigned a number to each paper. People in the copy office then recopied the entire text three times. This way, examiners couldn't tell who wrote the paper. The papers were reviewed by several officials.

Pu Songling, a writer from the Qing dynasty, described the "seven transformations of the candidate":

When he first enters the examination compound and walks along, panting under his heavy load of luggage, he is just like a beggar. Next, while undergoing the personal body search and being scolded by the clerks and shouted at by the soldiers, he is just like a prisoner. When he finally enters his cell and, along with the other candidates, stretches his neck to peer out, he is just like the larva of a bee. When the examination is finished at last and he leaves, his mind in a haze and his legs tottering, he is just like a sick bird that has been released from a cage. While he is wondering when the results will be announced and waiting to learn whether he passed or failed, so nervous that he is startled even by the rustling of the trees and the grass and is unable to sit or stand still, his restlessness is like that of a monkey on a leash. When at last the results are announced and he has definitely failed, he loses his vitality like one dead, rolls over on his side, and lies there without moving, like a poisoned fly. Then, when he pulls himself together and stands up, he is provoked by every sight and sound, gradually flings away everything within his reach, and complains of the illiteracy of the examiners. When he calms down at last, he finds everything in the room broken. At this time he is like a pigeon smashing its own precious eggs. These are the seven transformations of a candidate.

Celebrations and Privileges

The middle of the main hall stairs in the imperial palace had a carving of the mythical turtle Ao. When the palace exam results were published, all successful candidates' names were read aloud to the emperor. Graduates received a green gown, a tablet (symbol of status), and boots. The top scholar was called Zhuàngyuán and stood on the Ao carving. This led to the saying "to have seized Ao's head," meaning to be the best in a field.

Shengyuan degree holders received some tax breaks. Metropolitan exam graduates could pay a fee to avoid exile for crimes or reduce punishments. Besides the jinshi title, palace exam graduates were also free from all taxes and forced labor.

Other Types of Exams

Military Exams

During Wu Zetian's rule, the government created military exams (武舉 Wǔjǔ) in 702. These were for choosing army officers. Military exams had the same levels as civil exams: provincial, metropolitan, and palace. Successful candidates received military versions of the Jinshi and Juren degrees.

The military exam had both written and physical parts. Candidates were supposed to know Confucian texts and Chinese military texts like The Art of War. They also had to show martial skills like archery and horsemanship. The local exam had three parts.

The first part tested mounted archery. Candidates shot three arrows while riding a horse at a target. A perfect score was three hits. Those who fell off their horse or missed all shots failed. The second part was held in a garden. Candidates shot five arrows at a target. They also had to bend a strong bow and perform exercises with a halberd (a type of spear). They also had to lift a heavy stone off the ground.

The third part involved writing from memory parts of the Seven Military Classics. But most military examinees found this too hard. They often cheated by bringing tiny books to copy. Examiners often ignored this because the physical tests were more important. The military exams were largely the same at all levels, just with tougher grading.

Military degrees were seen as less important than civil degrees. They didn't have the same prestige. Civil jinshi names were carved in marble, but military jinshi names were not. Soldiers often preferred commanders who weren't military exam graduates. This was because test-taking skills didn't always mean good army leadership. The final decision for military appointments often came from outside the exam system. Most famous military figures in Chinese history were actually civil degree holders.

Culture of the Exams

Language and Learning

All Chinese imperial exams were written in Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese. They used the regular script (kaishu), which is a common writing style today. Knowing Classical Chinese was very important in exam systems in other countries too, like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. Candidates had to be good at Confucian texts, writing essays and poetry in Classical Chinese, and writing in regular script. Because of the exam system, Classical Chinese became a basic education standard in these countries.

People who read Classical Chinese didn't need to speak Chinese to understand the text. This was because of its picture-like characters. Texts written in Classical Chinese could be understood by anyone who could read it, even if they spoke Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese. This shared writing tradition helped these countries communicate through "brush talk" (writing notes to each other) when they didn't share a spoken language.

In Korea and Japan, special writing systems were developed to help readers understand Classical Chinese. These systems added markers to the Chinese text to show their own language's pronunciation and grammar. Chinese characters were also adapted to write Korean and Japanese in their native word order.

Poetry in Exams

One big question about the imperial exams was whether testing poetry writing was useful. During the Tang dynasty, a poetry section was added. Candidates had to write a shi poem and a fu composition. This poetry requirement stayed for many decades, even with some arguments against it.

During the Song dynasty, in the late 1060s, Wang Anshi removed the poetry sections. He said they weren't important for government jobs. But Su Shi argued that poetry helped with careful writing. He also said that grading poetry was more fair than grading essays because of its strict rules.

From the Yuan dynasty, poetry was removed from the exams. It was seen as not serious enough. It was brought back briefly in 1756 by the Qing dynasty.

Beliefs and Superstitions

The imperial exams also influenced traditional Chinese beliefs. The exam system was supposed to be based on Confucianism, which focused on logic and finding talented people. But in practice, people also believed in fate and the influence of gods. They thought that success or failure in the exams was decided by Heaven and other deities.

Zhong Kui was a god linked to the exam system. The story says he was a scholar who did very well on the tests. But he was unfairly denied first place by a corrupt system. In response, he took his own life and became a ghost. Many people who feared evil spirits worshiped Zhong Kui as a protector. The Strange Stories from the Examination Halls was a popular collection of stories among scholars. Many of these stories said that good deeds were rewarded with exam success by Heaven. Bad deeds led to failure, often because of ghosts.

Sometimes, people were treated unfairly because of their names. For example, the Tang dynasty poet Li He was discouraged from taking the tests. This was because his father's name sounded like jin, which was in jinshi. It was considered bad manners for a son to be called by his father's name.

Influence on Other Countries

Japan

Chinese laws and the exam system greatly influenced Japan during the Tang dynasty. In 728, Sugawara no Kiyotomo took part in the Tang exams. Near the end of the Tang era, Japan started its own exam system. This lasted for about 200 years during the Heian period (794–1185). Poets like Sugawara no Michizane wrote about their experiences with the exams.

Like the Chinese exams, the Japanese curriculum focused on Confucian texts. But Japanese exams changed over time. The xiucai exams became more popular than the jinshi because they were simpler. The Japanese exams were also never as open to common people as in China. By the 10th century, only students recommended by powerful people could take the exams. After the 11th century, the exams lost their practical value. Any candidate nominated by important people passed easily. The Japanese imperial exams slowly died out.

The exams were brought back in 1787 during the Edo period. These new exams were similar to the Chinese ones in content (Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism). But they only gave honorary titles, not official jobs. In the early Meiji era, Kanda Takahira suggested creating a Japanese recruitment system based on the Chinese imperial exams. But his idea didn't get enough support.

Korea

Korea directly participated in the Chinese imperial exam system in the 9th century. Many Sillans received degrees after passing the Tang exams.

The Korean examination system was started in 958 under Gwangjong of Goryeo. It was brought to Goryeo in 957 by a visiting scholar from China. Gwangjong liked the scholar and asked him to stay in Korea.

Some Korean exam practices became similar to the Chinese system. By the end of the Goryeo period, a military exam was added. The exams were held every three years. The exam levels were provincial, metropolitan, and palace, just like in China. Other practices, like including exams on Buddhism and worshiping Confucius, were unique to Korea. Outside China, Korea used the exam system the most. Even more people took exams in Korea than in China. Any free man (not a slave) could take the exams.

At the start of the Joseon period, 33 candidates were chosen from each triennial exam. This number later increased to 50. In comparison, China chose no more than 40 to 300 candidates after each palace exam. China was six times larger than Korea. By the Joseon period, high government jobs were closed to nobles who hadn't passed the exams. Over 600 years, the Joseon civil service chose more than 14,606 candidates in the highest-level exams. The exam system continued until 1894 when it was stopped. All Korean exams used the Idu script.

Vietnam

The Confucian exam system in Vietnam began in 1075 under the Lý dynasty Emperor Lý Nhân Tông. It lasted until 1919. During the Lý dynasty (1009–1225), the imperial exams had very little influence. Only four were held, producing a small number of officials. Later, during the Trần dynasty (1225–1400), Trần Thái Tông started using the Tiến sĩ (jinshi) exams to select students. In 1314, 50 Tiến sĩ were chosen in one exam.

For most of Vietnam's exam history, there were only three levels: interprovincial, pre-court, and court. A provincial exam was added by the Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1883) in 1807, and a metropolitan exam in 1825. Emperor Minh Mạng (r. 1820–1839) paid special attention to the exams. He even ate with newly chosen Tiến sĩ often. Although Confucian content was most important, material on Buddhism and Daoism was also included. In 1429, Lê Thái Tổ ordered famous Buddhist and Daoist monks to take the exams. If they failed, they had to give up their religious life. Elephants were used to guard the exam halls until 1843. Over 845 years of civil service exams in Vietnam, about 3,000 candidates passed the highest-level exams. Their names were carved on stone tablets in the Temple of Literature in Hanoi.

Influence in the West

Europeans knew about the imperial exam system as early as 1570. The Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) paid great attention to it. He liked how it used reason, unlike religious reliance on "apocalypse." Knowledge of Confucianism and the exam system spread widely in Europe after Ricci's journal was translated into Latin in 1614. In the 18th century, European thinkers like Voltaire and Montesquieu often discussed the imperial exams. Voltaire even said the Chinese had "perfected moral science."

The earliest evidence of exams in Europe dates to 1215 or 1219 in Bologna. These were mostly oral exams. Written exams didn't appear until 1702 at Trinity College, Cambridge. Germany started using an exam system around 1800. France adopted an exam system in 1791, but it failed after ten years.

English people in the 18th century, like Eustace Budgell, suggested copying the Chinese exam system. Adam Smith also recommended exams for jobs in 1776. In 1806, the British East India Company started a Civil Service College near London. This was based on recommendations from company officials who had seen the Chinese imperial exams. In 1829, the company introduced civil service exams in India. This set the idea of a qualification process for civil servants in England.

Both Thomas Babington Macaulay and Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh, who helped create the British civil service, knew about Chinese history. When the idea was discussed in parliament in 1853, some argued against it because it was a "Chinese system." But others argued for it, saying the minority Manchus had ruled China for over 200 years using it. The exam system was finally put in place in the British Indian Civil Service in 1855 and in England in 1870. Even ten years later, people still called it an "adopted Chinese culture."

After Britain successfully used competitive exams in India, similar systems were started in the United Kingdom and other Western countries. The development of the French and American civil services was influenced by the Chinese system. In 1870, William Spear wrote a book urging the United States government to adopt the Chinese exam system. Many American elites disliked the idea, calling it foreign and "un-American." As a result, the civil service reform in the United States was not passed until 1883.

Examinations in Modern China

1912–1949

After the Qing dynasty fell in 1912, Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the leader of the new Republic of China, created similar procedures. He set up an institution called the Examination Yuan, one of the five branches of government. However, this was quickly stopped due to chaos in China, like the Warlord era and the Japanese invasion. The Kuomintang government brought back the Examination Yuan in 1947 after Japan's defeat. This system continues today in Taiwan.

1949–Present

In the People's Republic of China (PRC), the government of Mao Zedong rejected the imperial exam system. Instead, they chose officials based on their loyalty to the ruling Communist Party. Since the economic reforms of the 1980s, the Civil Service uses exams to select and promote government workers.

In the Republic of China (ROC), the constitution says that a public servant cannot be hired without passing an exam. Once hired, the job usually lasts until retirement.

Organization

The examinations were given a formal structure and tier system during the Song dynasty. The exact number of tiers, their titles, degrees awarded, and names differed depending on the era and dynasty. Sometimes, exams of the same tier from different dynasties had different names. For example, the palace examination was called dianshi or yushi during the Song, but tingshi in the Ming. The lowest tier examinations were usually held annually, while higher tier examinations were held every three years.

| Dynasty | Exams held | Jinshi graduates |

|---|---|---|

| Tang (618–907) | 6,504 | |

| Song (960–1279) | 118 | 38,517 |

| Yuan (1271–1368) | 16 | 1,136 |

| Ming (1368–1644) | 89 | 24,536 |

| Qing (1644–1912) | 112 | 26,622 |

Degree types

By the Ming dynasty, the examinations and degrees formed a "ladder of success." Success usually meant graduating as jinshi, a degree similar to a modern PhD. Higher-placing graduates received special honors, like modern latin honors. The exam process started at the county level and included exams at the provincial and metropolitan levels. The highest level exam was at the palace, with successful candidates becoming jinshi.

- Tongsheng (童生, lit. "child student"): An examinee who passed the county/prefecture examination of the entry-level exams.

- Shengyuan (生員, lit. "student member"), commonly called xiucai (秀才, lit. "outstanding talent"): A scholar who passed the academy examination of the entry-level exams. Xiucai had special social benefits, like not having to do forced labor. They also had some immunity from physical punishments. They were divided into three classes based on their performance.

- Linsheng (廩生, lit. "granary student"): The best shengyuan, who received government payments for their achievements. The top linsheng could enter the Imperial Academy as gongsheng (貢生, lit. "tribute/selected student"). They could then take the provincial or even metropolitan exam directly.

- Anshou (案首, lit. "first desk"): The highest-ranking linsheng, who ranked first in the academy examination.

- Juren (舉人, lit. "recommended man"): A scholar who passed the provincial examination, held every three years.

- Jieyuan (解元, lit. "foremost among present scholars"): The juren who ranked first in the provincial examination.

- Gongshi (貢士, lit. "tribute scholar"): A scholar who passed the metropolitan examination, held every three years in the national capital.

- Jinshi (進士, lit. "advanced scholar"): A scholar who passed the palace examination, held every three years in the imperial palace.

- Jinshi jidi (進士及第, lit. "distinguished advanced scholar"): The first class in the palace examination, usually only the top three individuals.

- Jinshi chushen (進士出身, lit. "advanced scholar background"): The second class in the palace examination.

- Tong jinshi chushen (同進士出身, lit. "along with advanced scholar background"): The third class in the palace examination.

See also

- Bar exam

- Chinese classic texts

- Confucian court examination system in Vietnam

- Donglin Academy

- Education in the People's Republic of China

- Eight-legged essay, a literary form developed in association with examination requirements

- Four Books and Five Classics, Confucian works used in the examinations

- Gwageo, Korean national examination system begun in Unified Silla, expanded in Goryeo dynasty, and continued by the Joseon administration

- Hanlin Academy

- Huang Zongxi

- Imperial examination in Chinese mythology, cultural and mythological features related to the examinations

- Mandarin square

- Music Bureau

- Nine-rank system, a predecessor to the later imperial examination system

- Rulin Waishi, a Qing dynasty satirical novel that ridiculing the imperial examination and scholars around it.

- Scholar-bureaucrats, a class of educated government officials in Chinese history

- Wen Wu temple, official temples dedicated to the worship of the Civil and Martial Deities

Images for kids

-

Tang dynasty government hierarchy.

-

Song dynasty government hierarchy.

-

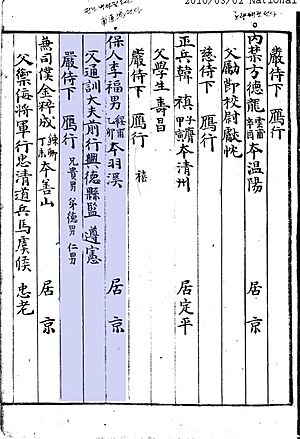

Ming dynasty government hierarchy.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |