Liang Qichao facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Liang Qichao

梁啓超 |

|

|---|---|

Liang Qichao in 1910

|

|

| Director of the Imperial Library of Peking | |

| In office December 1925 – June 1927 |

|

| Preceded by | Chen Renzhong |

| Succeeded by | Guo Zongxi |

| Minister of Finance of the Republic of China | |

| In office July 1917 – November 1917 |

|

| Premier | Duan Qirui |

| Preceded by | Li Jingxi |

| Succeeded by | Wang Kemin |

| Minister of Justice of the Republic of China | |

| In office September 1913 – February 1914 |

|

| Premier | Xiong Xiling |

| Preceded by | Xu Shiying |

| Succeeded by | Zhang Zongxiang |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 23, 1873 Xinhui, Guangdong, Qing China |

| Died | January 19, 1929 (aged 55) Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beiping (now Beijing), Republic of China |

| Political party | Progressive Party |

| Spouses |

Li Huixian

(m. 1891)Wang Guiquan

(m. 1903) |

| Children | 9 children, including Liang Sicheng and Liang Siyong |

| Education | Jinshi degree in the Imperial Examination |

| Occupation |

|

| Liang Qichao | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 梁啓超 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 梁启超 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Liang Qichao (born February 23, 1873 – died January 19, 1929) was an important Chinese politician, writer, and thinker. He greatly influenced how modern China changed politically. His ideas and writings inspired many Chinese scholars and activists. He also translated many Western and Japanese books into Chinese, bringing new ideas to young people.

When he was young, Liang Qichao joined his teacher Kang Youwei in a reform movement in 1898. After this movement failed, he went to Japan. There, he promoted the idea of a constitutional monarchy, where a king or queen shares power with a government chosen by the people. He also helped organize groups against the old dynasty.

After the 1911 revolution, he worked for the new government. He became unhappy with Yuan Shikai when Yuan tried to become emperor. Liang then led a movement against Yuan. After Yuan's death, Liang served as the finance chief. He also supported the New Culture Movement, which aimed for cultural changes, but he did not want a full political revolution.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Liang Qichao was born in a small village in Xinhui, Guangdong Province, on February 23, 1873. His father was a farmer and local scholar who taught him from a young age. Liang started writing essays when he was nine.

He passed his first big exam, the Xiucai degree, at age 11. At 16, he passed the Juren exam, becoming the youngest person to do so that year. In 1890, he tried the highest national exam, the Jinshi degree, in Beijing but did not pass. He never earned a higher degree.

Liang became very interested in Western ideas after reading a book called Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms. He then studied with Kang Youwei, a famous scholar who taught about foreign affairs. This made Liang even more interested in reforming China.

In 1895, Liang went to Beijing again for the national exam. He was part of the Gongche Shangshu movement, where scholars protested to the emperor. After failing the exam again, he stayed in Beijing. He helped Kang Youwei publish a newspaper and organize a group called the Society for National Strengthening. He also edited reform-focused newspapers in Hunan.

Reform Movements and Exile

Liang Qichao wanted to change the way China was governed by the Qing dynasty. He believed in a constitutional monarchy, where the emperor would share power. He and Kang Youwei wrote their ideas and sent them to the Guangxu Emperor. This effort is known as the Wuxu Reform or the Hundred Days' Reform. They wanted to end corruption and change the old exam system.

However, Empress Dowager Cixi and her supporters strongly opposed these changes. They thought the reforms were too extreme. In 1898, the Conservative Coup ended all reforms. Liang became a wanted man and had to flee to Japan, where he lived for the next 14 years.

In Japan, he continued to write and speak about democracy. He wanted a constitutional monarchy, not a full revolution like some other groups. He also traveled to Canada, Hawaii, and the United States, meeting leaders like Sun Yat-Sen and President Theodore Roosevelt. He visited Australia in 1900-1901, seeing how the different colonies united to form a new nation. He thought this could be a good example for China.

Political Career

Liang Qichao believed that for China to become a strong, modern nation, its people needed to become active citizens. He thought Chinese culture needed to change, not just its government. He believed that all Chinese groups should unite into one nation.

When the Qing dynasty was overthrown, the idea of a constitutional monarchy became less important. Liang joined his Democratic Party with other groups to form the Progressive Party. He disagreed with Sun Yat-sen's efforts against President Yuan Shikai.

In 1915, Liang opposed Yuan Shikai's plan to make himself emperor. He convinced his student Cai E to rebel, and many provinces declared their independence from Yuan. Liang also strongly supported China joining World War I on the side of the Allied powers. He believed this would help China's standing in the world. After trying to guide other politicians, he eventually left politics.

Even though his reforms didn't fully succeed, Liang Qichao's ideas about Chinese nationalism influenced later leaders like Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang.

Contributions to Journalism

As a Journalist

Many people consider Liang Qichao one of the most important figures in Chinese journalism. He showed that newspapers and magazines could be powerful tools for sharing political ideas.

Liang believed that journalism and history had the same goal: to show people the path to progress. He started his first newspaper, Qing Yi Bao, named after an old student movement. Being in Japan allowed him to write freely. He edited several important newspapers and published his ideas in journals like New Citizen.

He used his writings to spread his views on republicanism in China and beyond. He became a very influential journalist, using new types of magazines to share his thoughts on politics and culture. He also published articles in the magazine New Youth, promoting ideas of science and democracy. For Liang, journalism was a way to show his patriotism.

New Citizen Journal

Liang started a popular journal called New Citizen (Xinmin Congbao), first published in Japan in 1902. This journal covered many topics, including politics, religion, law, and international news.

In New Citizen, Liang created many new Chinese words for Western ideas and theories. He used the journal to share public opinion in China with readers far away. He hoped New Citizen would start a "new stage in Chinese newspaper history." The journal was published for five years and had an estimated 200,000 readers.

The Role of Newspapers

Liang believed in the great "power" of newspapers, especially their influence on government policies. He wrote that China was weak because information didn't flow freely between leaders, officials, and the people, or between China and the outside world. He criticized the Qing dynasty for controlling information.

Liang saw newspapers as a "weapon" for change. He said a newspaper was like a "revolution of ink, not a revolution of blood." He also believed newspapers could be an "educational program." He said they could gather all the thoughts of a nation and share them with everyone.

For example, he wrote a famous essay called "The Young China" in his newspaper Qing Yi Bao in 1900. This essay introduced the idea of a nation-state and argued that young revolutionaries held China's future. This essay was very influential during the May Fourth Movement in the 1920s.

However, Liang also felt that Chinese newspapers at the time were weak. They lacked money, faced social biases, and struggled with distribution because of poor roads. He thought many newspapers were just "mass commodities" that didn't truly influence the nation.

Literary Career

Liang Qichao was both a traditional Confucian scholar and a reformist. He wrote many articles explaining non-Chinese ideas about history and government. He wanted to inspire Chinese citizens to build a new China. He argued that China should keep its ancient Confucian teachings but also learn from Western political successes, not just their technology.

Liang helped shape ideas about democracy in China by combining Western scientific methods with traditional Chinese history. His works were influenced by Japanese scholars who used ideas like social Darwinism to promote strong national identity.

New History Ideas

Liang Qichao's ideas about history helped start modern Chinese historiography. He believed that "old historians" failed to build the national awareness needed for a strong, modern China. Liang wanted a "new history" that would guide China's future.

In 1902, while in Japan, Liang wrote "The New Historiography". He urged Chinese people to study world history to understand China better, not just Chinese history. He also criticized old ways of writing history that focused too much on dynasties instead of the nation, or on individuals instead of groups.

Translator

Liang was in charge of a translation office. He believed that translating Western works into Chinese was extremely important. He thought Westerners were successful politically, technologically, and economically, and China could learn from them.

He translated works by Western thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke. His essays were published in many journals, attracting interest from Chinese thinkers who were worried about China's weakness against foreign powers. He also introduced Western social and political ideas, like Social Darwinism, to Korea.

Poet and Novelist

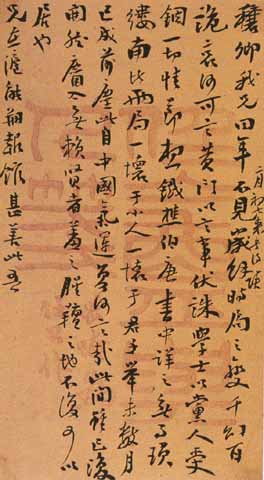

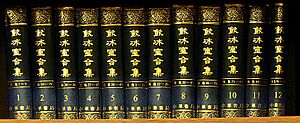

Liang also wanted to reform poetry and novels. His main literary work is Collected Works from the Ice-Drinker's Studio (Yinbingshi Heji), which has 148 volumes.

He named his studio "The Ice-drinker's Studio" because of an old saying: "Every morning, I receive the mandate [for action], every evening I drink the ice [of disillusion], but I remain ardent in my inner mind." This showed his strong desire to reform society through his writings, even when facing difficulties.

Liang also wrote fiction and essays about fiction. His novels often highlighted Western modernization and the need for reform in China.

Educator

In the early 1920s, Liang stopped being involved in politics and taught at universities in Shanghai and Peking. He founded a lecture association and invited important thinkers to China. He was a well-known scholar who introduced Western ideas and studied ancient Chinese culture.

As an educator, Liang Qichao believed that children were key to China's future. He thought education was very important for their growth and that traditional teaching methods needed to change. He wanted children to develop creative thinking and better understanding. He believed new schools were important for teaching children with new methods.

In his later years, he published studies on Chinese cultural history, literary history, and historiography. He also had a strong interest in Buddhism. Liang influenced many of his students, who became famous writers and scholars themselves.

Publications

- Introduction to the Learning of the Qing Dynasty (1920)

- The Learning of Mohism (1921)

- Chinese Academic History of the Recent 300 Years (1924)

- History of Chinese Culture (1927)

- The Construction of New China

- The Philosophy of Lao Tzu

- The History of Buddhism in China

- Collected Works of Yinbingshi, Zhonghua Book Co, Shanghai 1936, republished in Beijing, 2003, ISBN: 7-101-00475-X /K.210

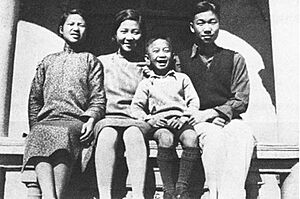

Family

Liang Qichao had two wives, Li Huixian and Wang Guiquan. Together, they had nine children. All of his children became successful in their fields, thanks to Liang's strong focus on their education. Three of his children became scientists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, including Liang Sicheng, a famous historian of Chinese architecture.

Legacy

Liang Qichao's ideas and writings had a lasting impact on China. He helped introduce many Western ideas and pushed for reforms that shaped modern Chinese thought and politics.

See also

- Gongche Shangshu movement

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |