Thomas Hobbes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Hobbes

|

|

|---|---|

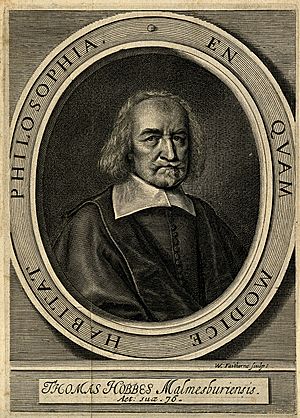

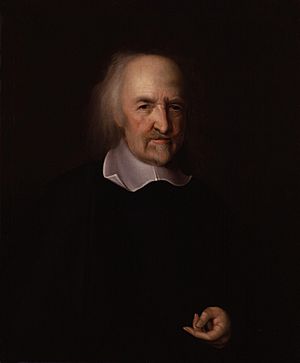

Portrait by John Michael Wright, c. 1669–1670

|

|

| Born | 5 April 1588 |

| Died | 4 December 1679 (aged 91) Derbyshire, England

|

| Education | Magdalen Hall, Oxford St John's College, Cambridge (B.A., 1608) |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, history, ethics, geometry |

|

Notable ideas

|

Social contract State of nature Bellum omnium contra omnes |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Thomas Hobbes (hobz; born April 5, 1588 – died December 4, 1679) was an important English philosopher. He is most famous for his 1651 book, Leviathan. In this book, he shared his ideas about the social contract theory, which is still studied today.

Besides political ideas, Hobbes also wrote about many other subjects. These included history, law, geometry, religion, and ethics. Many people see him as one of the main founders of modern political philosophy.

Contents

Thomas Hobbes's Life Story

His Early Years

Thomas Hobbes was born on April 5, 1588, in Malmesbury, England. His mother gave birth to him early because she was scared of the coming Spanish invasion. Hobbes later joked that "my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear." He had an older brother named Edmund and a sister named Anne.

We don't know much about Hobbes's childhood or his mother's name. His father, Thomas Sr., was a vicar (a type of priest). According to Hobbes's biographer, John Aubrey, his father was not well-educated. Thomas Sr. got into a fight and had to leave London. Because of this, Thomas and his siblings were raised by their uncle, Francis. Francis was a rich glove maker who had no children of his own.

School Days

Thomas Hobbes started school at Westport church when he was four. He then went to the Malmesbury school and later to a private school. This private school was run by Robert Latimer, a graduate of the University of Oxford. Hobbes was a good student.

Between 1601 and 1602, he went to Magdalen Hall at Oxford University. There, he studied scholastic logic and mathematics. The head of the college, John Wilkinson, was a Puritan and influenced Hobbes. Before going to Oxford, Hobbes translated a play called Medea by Euripides from Greek into Latin verse.

At university, Hobbes seemed to follow his own study plan. He wasn't very interested in the traditional academic learning of the time. He finished his B.A. degree in 1608.

Working for the Cavendish Family

After university, Hobbes became a tutor for William, the son of William Cavendish, 1st Earl of Devonshire. This started a long connection with the Cavendish family. William Cavendish became an Earl in 1626 but died two years later. His son, also named William, became the 3rd Earl. Hobbes worked as a tutor and secretary for both of them.

In 1610, Hobbes went on a "grand tour" of Europe with the younger William Cavendish. This trip lasted until 1615. During this tour, Hobbes learned about European science and new ways of thinking. This was very different from the older scholastic philosophy he had learned at Oxford. In Venice, he met Fulgenzio Micanzio, a scholar who worked with Paolo Sarpi.

Hobbes spent a lot of time studying classic Greek and Latin writers. In 1628, he published a major translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War. This was the first time this Greek work was translated into English from a Greek manuscript.

Hobbes also spent some time with famous writers like Ben Jonson. He even worked briefly for Francis Bacon, helping him translate some of his Essays into Latin. However, Hobbes didn't start focusing on philosophy until after 1629. In June 1628, his employer, the Earl of Devonshire, died from the Bubonic plague. His widow, Countess Christian, then let Hobbes go.

Time in Paris (1629–1637)

In 1629, Hobbes quickly found new work as a tutor for Gervase Clifton's son. He spent most of this time in Paris. By November 1630, he was back with the Cavendish family, tutoring William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, the son of his previous student.

For the next seven years, while tutoring, Hobbes also learned more about philosophy. He became very curious about important philosophical discussions. In 1636, he visited Galileo Galilei in Florence. Galileo was under house arrest at the time. Hobbes also regularly joined philosophical groups in Paris, led by Marin Mersenne.

Hobbes became very interested in the idea of motion and how things move. He wanted to create a system of thought that would explain everything. His plan was to write three main books:

- First, a book about the "body" (physical world). This would explain how everything in the universe works through motion.

- Second, a book about "man." This would explain how human senses, knowledge, and feelings work.

- Finally, his most important book, about the "state" or society. This would explain why people form societies and how they should be governed to avoid chaos.

Back in England (1637–1641)

Hobbes returned to England from Paris in 1637. England was facing a lot of problems and disagreements, which interrupted his philosophical work. By 1640, he had written a short book called The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic. It wasn't officially published but was shared among his friends. A copied version was published without his permission about ten years later.

Many of Hobbes's political ideas in The Elements of Law were similar to those in his later, more famous book, Leviathan. This shows that the events of the English Civil War didn't change his core ideas much. However, in Leviathan, he changed his view on how much people's consent is needed to create a government.

In November 1640, the Long Parliament began. Hobbes felt that his writings had made him unpopular, so he went back to Paris. He stayed there for 11 years. In Paris, he rejoined Mersenne's group. He also wrote a critique of Descartes's Meditations on First Philosophy. This was published in 1641.

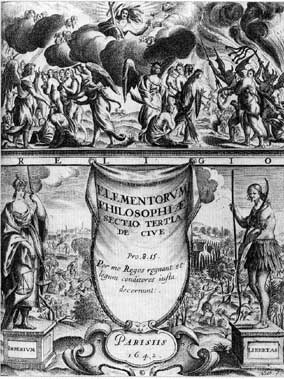

Hobbes also worked on the third part of his main project, De Cive. He finished it in November 1641. It was first shared privately but was well-received. Many of its ideas were later used in Leviathan. He then focused on the first two parts of his work. He also published a short paper on optics in 1644. He gained a good reputation in philosophy. In 1645, he was chosen with Descartes and others to judge a debate about squaring the circle (a famous geometry problem).

During the Civil War (1642–1651)

The English Civil War started in 1642. As the royalist side began to lose in 1644, many royalists came to Paris. Hobbes met many of them. This made him more interested in politics again. His book De Cive was republished and shared more widely.

In 1647, Hobbes became a math tutor for the young Charles, Prince of Wales, who was in Paris. This job lasted until 1648.

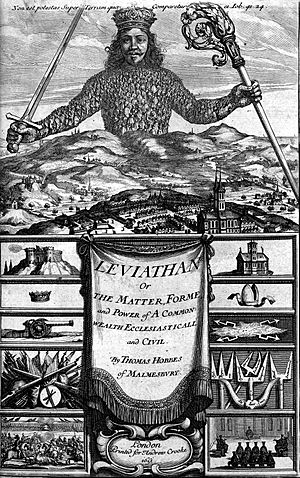

Being around the exiled royalists led Hobbes to write Leviathan. This book explained his ideas about government during the political crisis of the war. Hobbes compared the State to a huge monster (leviathan) made up of people. He said it was created because humans needed it, but it could be destroyed by disagreements and human emotions. The book ended by asking if people had the right to change their loyalty if their ruler could no longer protect them.

While writing Leviathan, Hobbes stayed in or near Paris. In 1647, he had a serious illness that kept him sick for six months. After recovering, he finished the book by 1650. Around this time, De Cive was also translated into English.

In 1650, a copied version of The Elements of Law was published without his permission. It was split into two smaller books. In 1651, the English translation of De Cive was published. Finally, his big work, Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil, came out in mid-1651.

Leviathan had a famous picture on its cover. It showed a crowned giant, made of tiny human figures, holding a sword and a crozier. The book had an immediate impact. Hobbes became both praised and criticized more than any other thinker of his time. Its publication ended his connection with the exiled royalists, who were angry about its ideas. The book's secular (non-religious) ideas also angered both Anglican and French Catholic groups. Hobbes asked the English government for protection and returned to London in late 1651. He was allowed to live a private life there.

Later Life and Challenges

In 1658, Hobbes published the last part of his philosophical system, called De Homine. This completed the plan he had started over 20 years earlier. De Homine mostly focused on a detailed theory of vision. Hobbes also continued to write philosophical works and some controversial papers on geometry.

After the king returned to power (the Stuart Restoration), Hobbes became more well-known. "Hobbism" became a term used to describe ideas that society disapproved of. However, the young king, Charles II, remembered Hobbes from his tutoring days. He called Hobbes to court and gave him a pension of £100.

The king helped protect Hobbes in 1666. The House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism. On October 17, 1666, they ordered a committee to look into books that promoted atheism or blasphemy, specifically mentioning Hobbes's Leviathan. Hobbes was very scared of being called a heretic. He burned some of his papers that might cause trouble. He also studied the laws about heresy. He wrote an appendix to his Latin translation of Leviathan (published in Amsterdam in 1668). In it, he argued that there was no court left to judge heresy and that Leviathan did not go against the main Christian beliefs.

Because of this bill, Hobbes could never publish anything in England about human behavior again. The 1668 edition of his works had to be printed in Amsterdam because he couldn't get permission in England. Other writings were not published until after he died. These included Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England. Despite these problems, his reputation in other countries was very strong.

Hobbes spent his last few years with his patron, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire, at Chatsworth House. He had been friends with the Cavendish family since 1608. After Hobbes died, many of his writings were found at Chatsworth House.

His final works included an autobiography in Latin poetry in 1672. In 1673, he translated four books of Homer's Odyssey into English. This led to a complete translation of both the Iliad and Odyssey in 1675.

His Death

In October 1679, Hobbes became ill with a bladder disorder. He then had a paralytic stroke and died on December 4, 1679, at the age of 91. He passed away at Hardwick Hall, which was owned by the Cavendish family.

His last words are said to have been "A great leap in the dark." He was buried in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire.

Hobbes's Political Ideas

Hobbes was inspired by the scientific ideas of his time. He wanted his political theory to be like a geometry system, where conclusions logically followed from clear starting points. His main idea was that a state or society can only be safe if it has a ruler with absolute power. This means that no person can have property rights against the ruler, and the ruler can take people's goods if needed. This idea was important because King Charles I had tried to raise money without Parliament's permission.

Hobbes disagreed with Aristotle's idea that humans are naturally social and become their best selves as citizens in a city-state. Hobbes believed humans were different.

Leviathan: A Strong Government

In Leviathan, Hobbes explained his ideas about how states and governments are formed and how they become legitimate. A large part of the book shows why a strong central government is needed to prevent chaos and civil war.

Hobbes started by thinking about humans as machines driven by their feelings. He imagined what life would be like without any government. He called this the "state of nature." In this state, everyone would have the right to do anything they wanted. Hobbes argued that this would lead to a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes).

In such a state, people would be afraid of death. They would also lack basic comforts and hope for a better life. To avoid this terrible situation, people agree to a social contract. Through this contract, they create a civil society and establish a sovereign authority (a ruler or government).

According to Hobbes, individuals give up some of their rights to this authority in exchange for protection. The power of this ruler cannot be challenged. This is because the ruler's power comes from the people themselves, who gave up their own power for safety. Hobbes believed that people are responsible for all decisions made by the ruler. He said, "he that complaineth of injury from his sovereign complaineth that whereof he himself is the author."

Hobbes did not believe in the idea of separation of powers (like dividing government into executive, legislative, and judicial branches). He thought the ruler should control all aspects of society: civil matters, the military, the courts, and even religious affairs.

Disagreements and Debates

Debates with John Bramhall

In 1654, Bishop John Bramhall published a small book called Of Liberty and Necessity, which was aimed at Hobbes. Bramhall, who believed strongly in free will, had met Hobbes and debated with him. He wrote down his views and sent them to Hobbes privately for a response. Hobbes replied, but he didn't intend for his reply to be published. However, a French friend copied Hobbes's reply and published it.

Bramhall responded in 1655 by publishing everything that had passed between them. In 1656, Hobbes replied with The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance. This book strongly argued for Determinism, the idea that all events are decided by things that happened before them. This debate was very important in the history of the free-will discussion. Bramhall continued the argument in 1658 with another book.

Debates with John Wallis

Hobbes was not a fan of the way universities were run at the time. He criticized them in Leviathan. He also published De Corpore, which contained some controversial ideas about mathematics and an incorrect proof for the squaring of the circle (a problem that cannot be solved with a compass and straightedge).

This led mathematicians to criticize him. John Wallis became one of his most persistent opponents. From 1655, when De Corpore was published, Hobbes and Wallis argued for almost 25 years. Hobbes never admitted his mistake about squaring the circle. Their debate became one of the most famous arguments in mathematical history.

Hobbes's Religious Views

Hobbes's religious beliefs are still debated today. Some people think he was an atheist, while others believe he was a Christian. In The Elements of Law, Hobbes argued for the existence of God, saying God is "the first cause of all causes."

Many people at the time accused Hobbes of being an atheist. Bishop Bramhall said Hobbes's teachings could lead to atheism. Hobbes always defended himself against these claims. He wrote that "atheism, impiety, and the like are words of the greatest defamation possible."

In Hobbes's time, "atheist" was often used to describe people who believed in God but not in divine providence (God's guidance). Or it was used for people whose beliefs seemed to go against traditional Christianity. This makes it hard to know exactly what people meant by "atheist" back then.

Hobbes did hold some views that disagreed with the church teachings of his time. For example, he often argued that there are no non-physical things. He believed that everything, including thoughts, God, heaven, and hell, are made of matter in motion. He said that "though Scripture acknowledge spirits, yet doth it nowhere say, that they are incorporeal." Like John Locke, he also believed that true revelation (God's message) could never go against human reason. However, he also argued that people should accept religious revelations and their interpretations if their ruler commanded it, to avoid war.

When Hobbes was on his grand tour in Venice, he met Fulgenzio Micanzio. Micanzio worked closely with Paolo Sarpi, who had written against the Pope's power in worldly matters. Sarpi and Micanzio argued that God created human nature, and human nature showed that the state should be independent in worldly affairs. When Hobbes returned to England, he translated Sarpi's letters, which were shared among the Duke's friends.

Images for kids

-

Tomb of Thomas Hobbes in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Hobbes para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Hobbes para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |