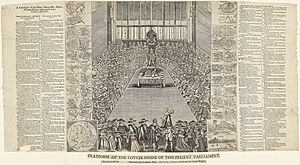

Long Parliament facts for kids

The Long Parliament was a special English Parliament that met from 1640 to 1660. It got its name because it decided it could only be ended if its members agreed. They didn't agree to end it until 1660, after the English Civil War and near the end of a time when England had no king, called the Interregnum.

King Charles I called this Parliament because he needed money. He had spent a lot on wars with Scotland, known as the Bishops' Wars. Before this, Parliament hadn't met for 11 years. A short Parliament met for only three weeks in spring 1640, but it didn't help the King. So, Charles I called the Long Parliament to meet on November 3, 1640.

This Parliament sat from 1640 until 1648. Then, soldiers from the New Model Army removed many members. The remaining members became known as the Rump Parliament. Later, Oliver Cromwell ended the Rump Parliament in 1653. He then set up new parliaments.

After Cromwell died in 1658, the Rump Parliament came back in 1659. In 1660, General George Monck allowed the members who had been removed in 1648 to return. This helped them pass laws to bring back the King, a time known as the Restoration. After this, the Long Parliament finally ended. A new Parliament, called the Convention Parliament, was then elected.

Some important members of the Long Parliament, like Sir Henry Vane the Younger and General Edmond Ludlow, were not part of its final actions. They believed the Parliament was not properly ended. They thought General Monck had planned things to bring back King Charles II of England. Monck was rewarded with a special title for his actions.

Later, historians saw the Long Parliament as a very important time. Some believed its actions helped create ideas about freedom and government that influenced events like the American Revolutionary War.

Contents

- The Execution of Strafford

- Committees of the Long Parliament

- The Grand Remonstrance

- First English Civil War

- Second English Civil War

- The Rump Parliament (1648–1653)

- The Rump Parliament Returns (1659–1660)

- Restoration and Dissolution (1660)

- Aftereffects: Royalist and Republican Ideas

- Notable Members of the Long Parliament

- Timeline of Key Events

- See also

The Execution of Strafford

King Charles I needed money for his wars with Scotland. In April 1640, he called Parliament after 11 years. But Parliament refused to give him money unless he made some changes. So, he closed it after only three weeks. This was called the Short Parliament.

After another defeat by the Scots, Charles had to call new elections in November. This new Parliament, the Long Parliament, had many members who opposed the King. They were led by John Pym.

Parliament quickly received many requests to remove bishops from the Church of England. People were worried that the Church was becoming too much like the Catholic Church. They also feared that King Charles might make an alliance with Spain.

Ending the King's absolute rule was important for England and for the Protestant religion. Instead of directly attacking the King, Parliament decided to go after his "bad advisors." This showed that even if the King was above the law, his helpers were not. It also made others think twice about their actions.

Their main target was the Earl of Strafford, who had been a powerful leader in Ireland. Strafford wanted King Charles to use the army to arrest members of Parliament. But Pym acted first. On November 11, Strafford was arrested and sent to the Tower of London. Other targets fled the country. Archbishop William Laud was also arrested in December 1640.

At his trial in March 1641, Strafford faced many charges. But it wasn't clear if these charges were legally "treason." If he was set free, his opponents would be in danger. So, Pym pushed for a special law, called a "bill of attainder," to declare Strafford guilty and order his execution.

King Charles said he would not sign the law. But on April 21, most members of Parliament voted for it. On May 1, rumors spread that there was a plan to free Strafford from the Tower. This led to large protests in London. On May 7, the House of Lords also voted for his execution. Fearing for his family, King Charles signed the death warrant on May 10. Strafford was executed two days later.

Committees of the Long Parliament

On November 5, 1640, Parliament created several groups, called committees, to handle its work. The first was the Committee for Privileges and Elections. It was led by John Maynard. The next day, November 6, Parliament set up the Grand Committee for Religion.

The Grand Remonstrance

After Strafford's execution, Parliament began to make changes to the government. They gave King Charles £400,000. The Triennial Acts made sure Parliament would meet at least every three years. If the King didn't call it, members could meet on their own.

Parliament also declared that collecting taxes without its approval was illegal. This included special taxes like "Ship money." Courts like the Star Chamber and High Commission were also abolished. These courts had been used by the King to punish people without a fair trial.

Many people who later supported the King, like Edward Hyde, agreed with these early changes. However, they disagreed with John Pym and his supporters because they didn't trust King Charles to keep his promises. The King had broken promises before. He and his wife, Henrietta Maria, even told foreign ambassadors that any changes were temporary. They planned to take back power later if needed.

During this time, people believed that "true religion" and "good government" were connected. Most people thought a king was necessary, but they disagreed on how much power he should have over the Church. Royalists supported a Church of England led by bishops chosen by the King. Most Parliamentarians were Puritans. They believed the King should answer to church leaders chosen by their communities.

The term "Puritan" included many different groups. Some just didn't like the changes made by Archbishop Laud. Presbyterians, like Pym, wanted to change the Church of England to be more like the Church of Scotland. Independents believed the government shouldn't control the church at all. Many Independents were also political radicals.

The presence of bishops in the House of Lords became a problem. They often blocked Parliament's reforms. Tensions grew even more in October 1641 when the Irish Rebellion broke out. Both the King and Parliament wanted to raise troops to stop it, but neither trusted the other to control the army.

On November 22, the House of Commons passed the Grand Remonstrance by a close vote. This was a long list of over 150 complaints against the King. It also suggested solutions, like church reform and Parliament controlling who the King appointed as ministers. Parliament also tried to take control of the army and navy through the Militia Ordinance. King Charles rejected the Grand Remonstrance and refused to approve the Militia Ordinance. At this point, moderate members like Hyde decided Pym and his supporters had gone too far, and they began to support the King.

First English Civil War

Growing unrest in London led to riots in December 1641. The bishops stopped attending the House of Lords because of the angry crowds. On December 30, King Charles convinced 12 bishops to sign a complaint. They said any laws passed by the Lords without them were illegal. Parliament saw this as the King trying to close Parliament. All 12 bishops were arrested.

On January 3, 1642, King Charles ordered his lawyer to charge five members of the House of Commons with treason. These were John Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Arthur Haselrig, and William Strode. This confirmed fears that the King would use force against Parliament. The members were warned and escaped arrest.

Soon after, King Charles left London with many of his supporters. This was a big mistake. He left behind England's largest weapons store and the wealth of London. This gave his opponents control of both houses of Parliament. In February, Parliament passed a law to remove bishops from the House of Lords. Charles approved it, planning to take back all these changes later with an army.

In March 1642, Parliament declared that its own laws, called "Parliamentary Ordinances," were valid even without the King's approval. The Militia Ordinance gave Parliament control of local militias, or trained soldiers. The London militia was very important because it could protect Parliament. King Charles declared Parliament to be in rebellion and began raising his own army.

By the end of 1642, Charles set up his court in Oxford. Royalist members of Parliament joined him there, forming the Oxford Parliament. In 1645, Parliament decided to fight the war until the end. They passed the Self-denying Ordinance, which meant members of Parliament had to give up their military commands. They then formed the New Model Army under Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell. The New Model Army quickly defeated Charles's forces. By early 1646, the King was close to defeat.

Charles left Oxford in disguise on April 27. On May 6, Parliament learned that David Leslie, the Scottish commander, had the King in custody. Charles ordered his governor to surrender, and the Scots took the King to Newcastle. This marked the end of the First English Civil War.

Second English Civil War

Many Parliamentarians thought that losing the war would force King Charles to make a deal. But they didn't understand him. Charles believed God would not let rebels win. This deep belief meant he refused to make any real changes. He knew his opponents were divided. He used his position as King of both Scotland and England to make these divisions worse. He thought he was essential to any government. But by 1648, key people realized it was pointless to negotiate with someone who couldn't be trusted.

In Scotland, the Bishops Wars had led to a Presbyterian government and church. The Scots wanted to keep this. The 1643 Solemn League and Covenant was signed because they worried what would happen if Charles defeated Parliament. By 1646, they saw Charles as less of a threat than the Independents in England. The Independents didn't want a single Presbyterian church for England and Scotland. Cromwell even said he would fight against it.

In July, the Scots and English offered Charles the Newcastle Propositions, but he rejected them. His refusal to negotiate created a problem for the Scots. Even if Charles agreed to a Presbyterian union, Parliament might not approve it. Keeping him was too risky. In February 1647, the Scots handed Charles over to Parliament and returned to Scotland.

In England, Parliament faced problems like the cost of the war, a bad harvest, and the plague. The Presbyterian group had support from London's trained soldiers and other armies. By March 1647, the New Model Army was owed a lot of unpaid wages. Parliament ordered them to Ireland, saying only those who went would be paid. The soldiers demanded full payment for everyone first. Parliament then tried to disband the army.

The New Model Army refused to be disbanded. In early June, King Charles was taken from his Parliament guards by soldiers. He was presented with the Army's terms, which were more lenient than the previous ones. But Charles rejected them. On July 26, pro-Presbyterian protesters forced their way into Parliament, demanding the King be invited to London. In early August, Fairfax and the New Model Army took control of the city. On August 20, Cromwell went to Parliament with soldiers and forced a law to cancel all Parliament's actions since July 26. This led to many Presbyterian members leaving.

In late November, the King escaped his guards and went to Carisbrooke Castle. In April 1648, a group called the Engagers gained power in the Scottish Parliament. In exchange for putting him back on the English throne, Charles agreed to make England Presbyterian for three years and suppress the Independents. But his refusal to take the Covenant himself divided the Scots. The Kirk Party didn't trust Charles and opposed an alliance with English and Scots Royalists.

After two years of talks, Charles finally had a plan for Royalists, some English Presbyterians, and Scots to rise up. But they didn't coordinate well, and the Second English Civil War was quickly put down.

The Rump Parliament (1648–1653)

After the Second English Civil War, disagreements grew among Parliament's groups. This led to Pride's Purge on December 7, 1648. Under orders from Henry Ireton, Cromwell's son-in-law, Colonel Pride stopped and arrested 41 members of Parliament. Many of these removed members were Presbyterians. Sir Henry Vane the Younger left Parliament in protest of this action. He was not involved in the execution of King Charles I, but Cromwell was.

After these members were removed, the remaining part of Parliament was called the Rump Parliament. This group arranged for the trial and execution of Charles I on January 30, 1649. They also set up the Commonwealth of England in 1649, a time when England was a republic without a king.

Henry Vane the Younger was convinced to rejoin Parliament in February 1649. A Council of State was formed to govern the country. Sir Henry Vane became a member and was even President for a time. As Treasurer and Commissioner for the Navy, he was in charge of the navy.

Cromwell knew that as long as the Long Parliament, with members like Vane, was meeting, he couldn't become a dictator. Henry Vane was working on a bill to reform Parliament. Cromwell knew that if this bill passed, and a new Parliament was elected fairly, it would be impossible to take away people's freedoms. According to General Edmond Ludlow, this bill would have made Parliament more representative and fairer.

Cromwell decided to act. He entered the Parliament meeting. He was dressed simply. As the Speaker was about to ask for a vote, Cromwell whispered, "Now is the time." He then stood up, his face red with anger. He strongly criticized the Parliament. He then stamped his foot, and soldiers entered. Cromwell shouted, "You are no Parliament; I say you are no Parliament; begone, and give place to honester men."

The members were shocked. Vane tried to speak, but Cromwell yelled, "Sir Harry Vane! Sir Harry Vane! Good Lord deliver me from Sir Harry Vane!" He then grabbed the official papers, took the bill from the clerk, and forced the members out. He locked the doors, put the key in his pocket, and left.

Oliver Cromwell forcibly ended the Rump Parliament in 1653. It seemed to be planning to stay in power instead of holding new elections. After this, other parliaments followed, including Barebone's Parliament and the First, Second, and Third Protectorate Parliaments.

The Rump Parliament Returns (1659–1660)

After Richard Cromwell, Oliver's son, was removed from power in April 1659, army officers called the Rump Parliament back. It met on May 7, 1659. But after five months, it again disagreed with the army, led by John Lambert. So, it was forcibly dissolved again on October 13, 1659. Sir Henry Vane was again a key leader for the idea of a republic against the army's power.

People who had worked for Oliver Cromwell wanted things to stay the same. Henry Vane was elected to Parliament several times. He managed the debates in the House of Commons. One of Vane's speeches effectively ended Richard Cromwell's time in power. He said that the English people had fought hard for their freedom. He questioned who Richard Cromwell was and why he should be their leader. Vane declared he would never accept such a man as his master.

This speech was very powerful. The Rump Parliament, which Oliver Cromwell had closed in 1653, was called back by the army officers on May 6, 1659.

Edmond Ludlow tried to help the army and Parliament get along, but it didn't work. Parliament ordered soldiers to protect them. In October 1659, Colonel Lambert and other army members stopped Parliament from meeting again. Parliament was closed by military force until the army and Parliament leaders could find a solution. A group called the Committee of Safety then took over.

During these problems, the Council of State still met. Lord President Bradshaw, though very ill, spoke strongly against the army's actions. He said he couldn't listen to such disrespect for the government. He then left his public duties.

The army officers tried to reach an agreement with Parliament's leaders. On October 15, 1659, they appointed people to find ways to run the country. On October 26, they appointed a new Committee of Safety. On November 1, this committee started to prepare a plan for a free state.

General Fleetwood and others in the army were suspected of possibly working with Charles II. Edmond Ludlow said that the army leaders were trying to destroy Parliament and bring back the King. He warned both the army and Parliament that if they didn't compromise, all the effort and lives lost for freedom would be wasted.

Negotiations began in December 1659 between Henry Vane (representing Parliament), Major Saloway, Colonel Salmon (from the army), and Vice-Admiral Lawson (from the navy). The navy strongly insisted that the army must obey Parliament. A plan was made to join forces with General Monck, but the republican party didn't know that Monck was secretly working with King Charles II.

Colonel Monck, who later became a hero for bringing back King Charles II, was disloyal to the Long Parliament and his oath. Ludlow said in January 1660 that Monck's plan was to destroy Parliament and bring back the King's son. This was shown by the many executions of Parliament members and generals after King Charles II returned. So, the return of King Charles II was not a free act of the Long Parliament. It happened because of Monck's military power.

General George Monck, who had been Cromwell's leader in Scotland, feared the army would lose power. He secretly changed his loyalty to the King. As he marched south, Lambert, who went to face him, lost support in London. The Navy declared its support for Parliament. On December 26, 1659, the Rump Parliament was restored to power.

On January 9, 1660, Monck arrived in London. His plans were revealed. Henry Vane the Younger was removed from the Long Parliament. Other key figures were questioned or arrested. Many army officers were removed from their positions. Parliament, now very weak, obeyed Monck's plans, even though they seemed designed to dissolve the Long Parliament.

Restoration and Dissolution (1660)

Monck initially showed respect to the Rump Parliament. But he soon found they didn't want to cooperate with his plan for new elections. The Rump Parliament believed Monck should answer to them and had its own plan for free elections. So, on February 21, 1660, Monck forced the members who had been removed by Pride's Purge in 1648 to return. This allowed them to prepare laws for the Convention Parliament. Some Rump Parliament members opposed this and refused to sit with the reinstated members.

On February 27, 1660, the new Council of State issued arrest warrants for army officers. They also got permission to arrest any Parliament member who hadn't sat since the removed members returned.

When Parliament was ready to pass the law to dissolve itself, a member named Crew suggested they should speak out against the "horrid murder" of the King. According to Ludlow, Mr. Thomas Scott, who had been misled by Monck, said he was proud to have been involved in the King's execution. He said he wanted his tombstone to read: "Here lies one who had a hand and a heart in the execution of Charles Stuart late King of England." After this, he and most of the members who had a right to be there left the House. So, less than a quarter of the legal members were present when the removed members, who had been voted out, decided to dissolve Parliament. Ludlow questioned if this was a true consent.

After calling for elections for a new Parliament to meet on April 25, the Long Parliament officially dissolved itself on March 16, 1660. On April 22, Major-General Lambert's group was broken up, and Lambert was taken prisoner.

Aftereffects: Royalist and Republican Ideas

Monck had kept saying he was loyal to the idea of a Commonwealth (a republic without a king). But once the new army was set up and a new Parliament, called a Convention, met, he allowed lords who had supported the King to return. He also broke his promise and let in new lords. Charles Stuart, the late King's eldest son, was told about these events. On Monck's advice, he went to Breda in Holland. From there, he sent letters and a declaration to the two Houses. The House of Commons then voted that the country should be governed by a King, Lords, and Commons. Charles Stuart was proclaimed King of England.

The Lord Mayor and citizens of London welcomed the King. Those who had lost battles and done nothing to bring about this change now acted as if they were in charge. They ordered soldiers to ride through London with swords drawn, suggesting they would use force to keep what they had gained by trickery.

Initially, seven people, and later 20, were executed for their roles. These included Chief Justice Coke, Major-General Harrison, Sir Henry Vane, and Mr. Thomas Scot. Among those who seemed most eager to please the new King was Mr. William Prynn. He tried to have everyone who had previously rejected the Stuart family also punished, but this failed.

John Finch, who had been accused of treason 20 years earlier and had fled, was now appointed to judge some of the people who should have judged him. Sir Orlando Bridgman, who had worked for Cromwell, was now in charge of these trials. He told the jury that no one, not even the people, had the power to force the King of England to do anything.

When creating the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion, which offered forgiveness for past actions, the House of Commons didn't want to exclude Sir Henry Vane, Sir Arthur Haslerig, and Major-General Lambert. They hadn't directly killed the King. But the House of Lords wanted Vane specifically excluded. They wanted him to be at the government's mercy so he couldn't promote his republican ideas. The two Houses agreed that the Commons would exclude Vane, and the Lords would ask the King not to execute him if he was found guilty. General Edmond Ludlow, who was loyal to the Rump Parliament, was also excluded.

According to the King's supporters, the Long Parliament was automatically ended when King Charles I was executed on January 30, 1649. This idea was confirmed in the trial of Henry Vane the Younger. Vane himself had agreed with this idea when he opposed Oliver Cromwell years earlier.

Henry Vane's trial was not fair. He was not given a lawyer and had to defend himself after years in prison. Sir Henry Vane argued:

- Can Parliament as a whole be charged with treason?

- Can someone acting for Parliament commit treason?

- Can actions done by Parliament's authority be questioned in a lower court?

- Can treason be committed against a king who is legally king but not in power?

King Charles II did not keep the promise made to Parliament. He executed Sir Henry Vane the Younger. The prosecutor openly said Vane "must be made a public sacrifice." One of the judges said, "We knew not how to answer him, but we know what to do with him."

Edmond Ludlow, one of the Parliament members excluded from forgiveness, fled to Switzerland after King Charles II returned. There, he wrote his memories of these events.

The Long Parliament began with the execution of Lord Strafford and effectively ended with the execution of Henry Vane the Younger.

The idea from republicans is that the Long Parliament wanted to create a balanced government with fair representation, similar to what later happened in America. Writings from Ludlow, Vane, and early American historians show this was their goal. They believed the Long Parliament would have succeeded if not for Oliver Cromwell's forceful actions. These included removing loyal members, the unlawful execution of King Charles I, and later dissolving the Rump Parliament. Finally, Monck's forceful dissolution of the reconvened Rump Parliament, when only a few members were present, also stopped their plans. Many believe this struggle was a preview of the American Revolution.

Notable Members of the Long Parliament

- Sir Arthur Haselrig

- Sir Benjamin Rudyerd

- Carew Raleigh

- Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles

- Edmond Ludlow

- Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon

- Sir Francis Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Trowbridge

- George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

- Sir Henry Vane the Elder

- Sir Henry Vane the Younger

- James Temple

- Sir John Coolepeper

- John Hampden

- John Pym

- Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland

- Sir Nicholas Crisp

- Nicholas Slanning

- Oliver Cromwell

- Oliver St John

- Sir Robert Harley

- Samuel Vassall

- Simonds D'Ewes

- Major-General Harrison

- William Lenthall

- William Russell, 1st Duke of Bedford

- William Strode

Timeline of Key Events

- Archbishop William Laud was arrested in December 1640.

- The Triennial Act was passed on February 15, 1641.

- A law saying the Long Parliament could not be dissolved without its consent was passed on May 11, 1641.

- Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, was executed on May 12, 1641.

- The Star Chamber court was abolished on July 5, 1641.

- Ship Money was declared illegal on August 7, 1641.

- The Grand Remonstrance was passed on November 22, 1641.

- The Militia Bill was proposed in December 1641.

- King Charles I tried to arrest the Five Members on January 4, 1642.

- The King and Royal Family left Whitehall in January 1642.

- The Militia Ordinance was agreed by Parliament on March 5, 1642.

- Parliament declared its laws valid without royal approval on March 15, 1642.

- The Adventurers' Act was passed to raise money for the Irish Rebellion of 1641 on March 19, 1642.

- The Solemn League and Covenant was signed on September 25, 1643.

- The Self-denying Ordinance was passed on April 4, 1645.

- Pride's Purge happened on December 7, 1648, starting the Rump Parliament.

- King Charles I was executed on January 30, 1649.

- Removed members of the Long Parliament were brought back by George Monck on February 21, 1660.

- The Long Parliament dissolved itself on March 16, 1660, after calling for new elections.

See also

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |