Henry Vane the Younger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Vane the Younger

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Sir Peter Lely

|

|

| 5th Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony | |

| In office 25 May 1636 – 17 May 1637 |

|

| Preceded by | John Haynes |

| Succeeded by | John Winthrop |

| Joint Treasurer of the Navy | |

| In office 1639–1642 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir William Russell |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Penington |

| Joint Treasurer of the Navy | |

| In office 1645–1650 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir William Russell |

| Succeeded by | Richard Hutchinson |

| Member of the English Parliament for Kingston upon Hull (UK Parliament constituency) |

|

| In office April 1640 – November 1650 Serving with Sir John Lister (died 1640) followed by Peregine Pelham

|

|

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Member of the English Council of State | |

| In office 17 Feb 1649 – 20 Apr 1653 |

|

| Lord President of the English Council of State | |

| In office 17 May 1652 – 14 June 1652 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Rolle |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Pembroke |

| Member of the English Council of State | |

| In office 19 May 1659 – 25 Oct 1659 |

|

| Member of the English Committee of Safety | |

| In office 26 Oct 1659 – 25 Dec 1659 |

|

| Member of the English Parliament for Whitchurch (UK Parliament constituency) |

|

| In office January 1659 – May 1659 Serving with Second seat was vacant

|

|

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Member of the English Parliament for Kingston upon Hull (UK Parliament constituency) |

|

| In office May 1659 – January 1660 Serving with Second seat was vacant

|

|

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | baptised 26 March 1613 Debden, Essex, England |

| Died | 14 June 1662 (aged 49) Tower Hill, London |

| Signature |  |

Sir Henry Vane (born 1613, died 1662) was an important English politician and leader. People often called him Harry Vane or Henry Vane the Younger to tell him apart from his father. He was known for his strong belief in religious tolerance, meaning people should be free to practice their own religion.

Vane spent a short time in North America. He served as the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. While there, he supported Roger Williams in creating the Rhode Island Colony. He also helped establish Harvard College. As governor, he stood up for Anne Hutchinson when she was criticized for teaching religious ideas in her home. This caused problems with the strict Puritan leaders in Massachusetts. After losing his re-election, Vane returned to England.

Back in England, he became a key leader for the Parliamentary side during the English Civil War. He worked closely with Oliver Cromwell. Vane did not take part in the execution of King Charles I. He also refused to approve of it. He served on the Council of State, which was like the government's executive branch. However, he disagreed with Cromwell on how to govern. He stepped away from power when Cromwell closed Parliament in 1653.

Vane returned to power briefly in 1659–1660. He fought for government reform and civil liberties. King Charles II saw him as a threat. After Charles II became king again, Vane was arrested. He was not given the same forgiveness as most people for their roles in the Civil War. Vane was accused of treason. He was found guilty in a trial where he couldn't properly defend himself. Charles II then withdrew his earlier promise of mercy. Henry Vane was executed on Tower Hill on June 14, 1662.

Vane was known as a skilled leader and a good negotiator. He believed strongly that the government should not control people's religious beliefs. Even though his ideas were not popular at the time, he managed to build support for his goals. His actions played a part in both the rise and fall of the English Commonwealth. His writings about politics and religion are still studied today. He is remembered in Massachusetts and Rhode Island as an early supporter of freedom.

Contents

Early Life and Beliefs

Henry Vane was born in Debden, Essex, England, and was baptized on March 26, 1613. He was the oldest child of Sir Henry Vane the Elder and Frances Darcy. His father was from a wealthy family and bought positions at court. By 1629, his father was the Comptroller of the Household.

Vane went to Westminster School. His classmates included future English politicians like Arthur Heselrige. A friend of Vane's, George Sikes, wrote that Vane had a religious awakening around age 14 or 15. After this, he became very serious about his faith. He then studied at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, even though he refused to take the required oaths. He also traveled in Europe, studying in places like Leiden and Geneva.

Vane's father was worried about his son's strong Puritan beliefs. He feared it would hurt Vane's chances at court. In 1631, his father sent him to Vienna to work for the English ambassador. Vane's writings from this time show he was involved in important diplomatic work.

His father tried many times to make him change his nonconformist views, but Vane refused. To worship freely, Vane decided to move to the New World. He joined the Puritan migration to America.

Time in New England

Vane arrived in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, in October 1635. He was described as a "young gentleman of excellent parts." Within a month, he became a "freeman" in the colony, which meant he could participate in government. He started helping with legal matters.

In May 1636, Vane was elected governor of the colony at just 23 years old. He faced many challenges, including religious, political, and military issues.

The colony was divided over Anne Hutchinson's beliefs. She held Bible study sessions at home, attracting many followers. She shared ideas that colonial leaders called "Antinomianism," which suggested that existing laws were not needed for salvation. Most older leaders, like John Winthrop, disagreed. Vane supported Hutchinson, as did the influential pastor John Cotton.

Vane upset some colonists by insisting on flying the English flag over Boston's fort. Many saw the Cross of St George on the flag as a symbol of the papacy. Later, Vane tried to resign as governor, but withdrew his resignation at the request of the Boston church.

During Vane's time as governor, a conflict with the Pequot tribe turned into war. A Massachusetts trader, John Oldham, was killed. Though Roger Williams warned that other tribes might be responsible, Governor Vane sent a force to confront the Pequots. This expedition only destroyed Pequot settlements and led to more attacks. In April 1637, Vane called a meeting to authorize the colonial militia to help other New England colonies in the war.

Vane lost the 1637 election to John Winthrop. The election was tense due to disagreements over how to treat John Wheelwright, another Hutchinson supporter. After the election, Anne Hutchinson was put on trial and banished. Many of her followers left the colony. Some, including Hutchinson, founded Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island, which later became part of Rhode Island.

Vane decided to return to England. Before leaving, he wrote a response to Winthrop's defense of the Act of Exclusion. This act limited immigration of people with different religious views. Despite their political differences, Vane and Winthrop later corresponded. Vane's time in America is remembered for his support of Harvard University and his help in establishing Rhode Island.

Historians believe Vane's experiences in Massachusetts made his religious views even stronger. He came to believe that all clergy, including Puritan ministers, should have less power. This idea guided his political actions in England. He wanted the government to stay out of church matters completely. This can be seen in the first Rhode Island charter in 1643, which guaranteed freedom of religion.

Return to England and Parliament

When Vane returned to England, he became the Treasurer of the Royal Navy in 1639. This job involved collecting the unpopular "ship money" tax. In June 1640, King Charles made him a knight. He married Frances Wray on July 1, 1640. His father then gave him most of the family's properties, including Fairlawn in Kent and Raby Castle, where Vane lived.

Vane was elected to both the Short and Long Parliaments, representing Hull. He had already connected with opponents of King Charles, like John Pym. In Parliament, Vane was seen as capable and persuasive. He was part of a younger group of Puritans who led the Long Parliament.

Vane played a key role in the 1641 impeachment and execution of the Earl of Strafford. Vane found secret notes his father had made about a council meeting. These notes suggested Strafford wanted the king to use the Irish Army to control England. The evidence was weak, so the impeachment failed. Pym then used a "bill of attainder" to have Strafford executed in May 1641. The way Pym got the notes caused a temporary rift between Vane and his father.

Vane supported major reforms in the Church of England. He introduced the "Root and Branch Bill" in May 1641. This bill aimed to change the church's governing structure. Vane argued that the existing church system was corrupt. Although the bill did not pass, it showed strong parliamentary support for church reform. When King Charles returned from Scotland, he removed both Vane and his father from their government jobs. This was revenge for their part in Strafford's execution.

English Civil War

In 1642, relations between the king and Parliament completely broke down. Both sides prepared for war. Parliament gave Vane his job back as Treasurer of the Navy. He helped bring naval support to Parliament. In June 1642, Charles rejected Parliament's demands. When fighting began, Vane joined the Committee of Safety, which managed Parliament's military actions.

In 1643, Parliament formed the Westminster Assembly of Divines to reform church governance. Vane was a lay representative for the Independent faction. He was sent to Scotland to ask for military help. The Scots agreed if England would adopt their Presbyterian church system. Vane, who opposed both Presbyterianism and the existing English church system, found a way to compromise. He proposed the Solemn League and Covenant. This agreement used vague language that allowed both sides to interpret it in their favor. This paved the way for Scotland to join the war.

After this success, Vane became a leader in Parliament. He was a key member of the Committee of Both Kingdoms, which coordinated war efforts between England and Scotland. Vane also suggested that Charles I should be removed and his son crowned king. Older generals disagreed, but Oliver Cromwell supported the idea.

Vane worked to find a compromise on religious issues. He sought to create ways for religious tolerance for the Independents. This showed his opposition to Presbyterianism. It also created a split between the pro-war Independents (led by Vane and Cromwell) and the pro-peace Scots and Presbyterians.

Parliament's Victory

Peace talks began in November 1644 but failed. Vane and the Independents were seen as a reason for this failure. They insisted on religious tolerance, which the Scots and Charles were not ready to accept.

Parliament began to reorganize its military. Vane and Cromwell supported the "Self-denying Ordinance." This law prevented military officers from serving in Parliament. They also supported creating the New Model Army, a national army that could fight anywhere.

After Parliament's victory at Naseby in June 1645, the first part of the civil war ended. Charles surrendered to the Scottish army. During this time, a new group called the Levellers emerged. Led by John Lilburne, they wanted more civil rights and opposed privileges for the aristocracy.

In 1646, Charles tried to make an alliance with Vane's faction against the Presbyterians. Vane refused, preferring that Parliament grant religious freedom. Vane's family home, Raby Castle, was damaged by royalists during the war. Parliament approved funds to fortify it.

Politics Between Wars

After the war, the Presbyterian group in Parliament was stronger than the Independents. They passed laws that went against Vane's views on religious tolerance. Vane realized that the Presbyterians could be as much of a threat as the Episcopalians.

In 1647, Vane and Oliver Cromwell, the army's leader, worked closely. The Presbyterian majority wanted to disband the army. But issues over pay and pensions led to negotiations with the army. Cromwell managed to calm the army, but Parliament still tried to remove Independent officers. Some Parliamentary leaders also tried to get the Scottish army to oppose the English army.

The Parliament army rebelled. Cromwell, possibly warned by Vane, seized King Charles. This forced the Presbyterian leaders to meet the army's demands. They also created a commission to deal with the army, and Vane was placed on it.

Negotiations between the army and Parliament were difficult. Mobs in London threatened Vane and other Independents. More than 50 Independent Members of Parliament (MPs), including Vane, left the city for the army's protection. The army then marched on London, and the Independents were seated in Parliament again.

Parliament debated the army's proposals for government and church. A key proposal for Vane was to remove any forced powers from the church. The king's response to these proposals divided the Independents. In November 1647, Charles escaped but was recaptured. He chose to ally with the Scots. Violence spread throughout the country.

War Continues

Fighting broke out again across the country. A mutiny in the Royal Navy in May 1648 forced Vane to try and regain the mutineers' support. By mid-July, the army controlled most of England. Cromwell defeated the Scottish army in August. Vane was one of the Parliament's representatives for negotiations with Charles in September 1648. He was blamed for the failure of these talks because he insisted on "unbounded liberty of conscience."

VANE, young in years, but in sage counsel old,

Than whom a better senator ne’er held

The helm of Rome, when gowns, not arms, repelled

The fierce Epirot and the African bold,

Whether to settle peace, or to unfold

The drift of hollow states hard to be spelled;

Then to advise how war may best, upheld,

Move by her two main nerves, iron and gold,

In all her equipage; besides, to know;

Both spiritual power and civil, what each means,

What severs each, thou hast learned, which few have done.

The bounds of either sword to thee we owe:

Therefore on thy firm hand Religion leans

In peace, and reckons thee her eldest son.

In late 1648, Vane argued that Parliament should form a government without the king. He believed this would make England the "happiest nation." On December 5, Parliament voted that the king's concessions were enough for an agreement.

On December 6, the military took control. Troops led by Thomas Pride surrounded the Houses of Parliament. They arrested MPs who supported negotiating with the king. Vane was not present that day. This event, known as "Pride's Purge", removed over 140 MPs. The remaining Parliament became known as the Rump Parliament. Its first task was the trial and execution of King Charles. Vane refused to attend Parliament during this process. He later said he opposed the king's trial. He continued his government duties, even signing papers on the day Charles was executed.

The Commonwealth and Oliver Cromwell

After Charles's execution, the House of Commons abolished the crown and the House of Lords. They created a Council of State to handle executive duties. Vane was appointed to it. He refused to join until he could do so without taking an oath that approved the king's execution. Vane served on many council committees. In 1650, he became president of the first Commission of Trade. This commission looked at trade, manufacturing, and colonies.

He helped manage supplies for Cromwell's conquest of Ireland. As a leader on the navy committee, he managed affairs during the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654). After the navy's poor performance in 1652, Vane led a committee to reform it. His reforms helped the navy succeed later in the war. He was also involved in foreign diplomacy.

Vane was also active in domestic affairs. He was on a committee that sold off Charles I's art collection. He made many enemies on committees that dealt with seizing assets from royalists. These enemies would later judge him.

The way Parliament handled executive duties was slow. This became a problem for Cromwell and the army, who wanted faster action. This disagreement created a rift between Cromwell and Vane. Parliament began to consider electoral reform. In January 1653, a committee led by Vane proposed changes. It suggested that voting rights be based on property ownership. It also aimed to remove "rotten boroughs" (areas with few voters controlled by wealthy people). The proposal also said some current members should keep their seats. Cromwell wanted a general election and opposed this plan.

On April 19, 1653, Parliamentary leaders, including Vane, promised Cromwell to delay action on the election bill. However, Vane likely tried to pass the bill the next day before Cromwell could react. Cromwell was warned and interrupted the proceedings. He brought troops into the chamber and ended the debate. He famously shouted at Vane, "O Sir Henry Vane, Sir Henry Vane; the Lord deliver me from Sir Henry Vane!" This ended the Commonwealth, and Cromwell became Lord Protector. Vane refused to join Cromwell's council.

During his retirement, Vane wrote The Retired Man's Meditations (1655), a complex religious book. In 1656, he wrote A Healing Question. This political work proposed a new government based on a constitution decided by a special convention. He used the phrase "the good old cause", which became a rallying cry for his republican group.

Cromwell's Secretary of State saw A Healing Question as an attack on Cromwell. Vane was ordered to appear before Cromwell's council. He refused to post a bond promising not to harm the government. He was arrested and imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle. While there, he wrote a letter to Cromwell, rejecting Cromwell's power. Vane was released on December 31, 1656.

During his retirement, Vane started a religious teaching group. His followers were known as "Vanists." He also supported writers who promoted his political views.

Richard Cromwell and After

After Oliver Cromwell died in September 1658, his son Richard became Lord Protector. Richard was not as skilled as his father. Political divisions reappeared. In December 1658, elections were called for a new parliament. Cromwell tried to prevent royalists and republicans from being elected. Vane, a republican leader, was targeted but won election for Whitchurch. In Parliament, republicans questioned Cromwell's power. They argued for limiting it and opposed the veto power of Cromwell's House of Lords.

Vane formed an alliance with republican military officers. These officers met secretly, which was against the law. Cromwell's supporters in Parliament tried too hard to control the military. Cromwell was forced to dissolve Parliament in April 1659. Cromwell then stepped down. After removing pro-Cromwell supporters from the military, Cromwell's council recalled the Rump Parliament in May.

In the restored Rump Parliament, Vane was appointed to the new Council of State. He also helped appoint army officers and managed foreign affairs. He examined the government's finances, which were in bad shape. General John Lambert was sent to stop a royalist uprising in August 1659. Lambert's support for certain religious groups led to his political downfall. After Parliament removed him and other officers from command, they marched on Parliament and dissolved it.

A committee of safety was formed, including army leaders and Vane. Vane agreed to serve because he feared the republican cause would fail without army support. This committee lasted only until December. Vane tried to stop Vice Admiral Lawson from blocking London with ships. When General George Monck's army advanced from Scotland, Lambert's military support disappeared. General Charles Fleetwood was forced to give Parliament House keys back to the Speaker. This led to the full Long Parliament being restored. Vane was expelled from the Commons for being part of the committee of safety. He was ordered to stay at Raby Castle. He returned to his house at Hampstead in February 1660.

That knave in grain

Sir Harry Vane

His case than most men's is sadder

There is little hope

He can scape the rope

For the Rump turned him o'er the ladder.

During the late 1650s, people debated how the government should be structured. Vane promoted his ideas through debates and pamphlets. In 1660, he published A Needful Corrective or Balance in Popular Government. This was a response to James Harrington's The Commonwealth of Oceana. Harrington believed power came from property ownership. Vane disagreed, arguing that power came from godliness.

The Restoration and Execution

In March 1660, the Long Parliament dissolved itself. Elections were held for the Convention Parliament, which met in May. This Parliament, mostly made up of royalists, declared Charles II king. He was restored to the throne on May 29, 1660. To prevent revenge for actions during the Interregnum, Parliament passed the Indemnity and Oblivion Act. This act forgave most actions. However, those directly involved in the king's execution were exceptions. Vane was also named as an exception after much debate.

Vane was arrested on July 1, 1660, by order of the king. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Parliament asked Charles to show mercy to Vane, and the king agreed to spare his life. Despite this, Vane remained in the Tower. His property income was seized. He was moved to the Isles of Scilly in October 1661 to limit his contact with potential plotters. He continued to write, mostly about religious topics. He tried to understand the political situation and his own condition. Vane believed that power came from God but rested with the people. He argued that if a king broke the "fundamental constitution," the people could regain their freedom.

In November 1661, the Cavalier Parliament demanded Vane's return to the Tower for trial. Charles delayed, but Parliament renewed the demand in January 1662. Vane was moved back to the Tower in April 1662. On June 2, 1662, he was accused of high treason against Charles II. His trial began on June 6. Vane was not allowed a lawyer, which was common for treason cases. He defended himself by arguing that Parliament had sovereign power during the civil war. He also said it was not possible to commit treason against a king who was not actually on the throne. The judges disagreed. The jury, made up of royalists, found him guilty after thirty minutes.

Vane tried to appeal his conviction. He also tried to get the judges to sign a document listing the problems with his trial, but they refused. Charles II heard about Vane's behavior during the trial. He decided Vane was too dangerous to live and withdrew his promise of mercy. On June 14, 1662, Vane was taken to Tower Hill and executed.

The diarist Samuel Pepys witnessed the event. He wrote that Vane gave a long speech, which was often interrupted. Trumpets were played to drown out his words. Pepys noted that Vane "changed not his colour or speech to the last, but died justifying himself and the cause he had stood for." Vane had prepared his speech carefully and given copies to friends. Many saw him as a martyr for his beliefs. His body was returned to his family and buried in Shipbourne, Kent.

Family Life

Henry Vane and his wife Frances had ten children. Of their five sons, only the youngest, Christopher, had children. Christopher inherited his father's estates and was later made Baron Barnard by William III.

Writings and Legacy

Many of Vane's speeches and writings were published during or after his lifetime. These include:

- A Brief Answer to a Certain Declaration (1637)

- The Retired Man's Meditations (1655)

- A Healing Question Propounded (1656)

- A Needful Corrective or Balance in Popular Government (1659)

- The Cause of the People of England Stated (written 1660–1662)

Vane was seen by people of his time as a talented leader and a powerful speaker. Even his royalist opponent, Clarendon, praised him. Clarendon wrote that Vane had "extraordinary parts, a pleasant wit, a great understanding, a temper not to be moved." He also noted Vane's "quick conception and a very sharp and weighty expression" in debates. John Milton wrote a sonnet praising Vane in 1652.

Vane's religious writings from his later years were often hard to understand. However, his reputation grew in the 1800s, especially in the United States. Historians like John Andrew Doyle praised his public spirit and foresight. William Wordsworth mentioned Vane in his sonnet Great Men Have Been Among Us. Charles Dickens included Vane in his A Child's History of England. Ralph Waldo Emerson listed Vane among great English figures.

In 1897, the Royal Society of the Arts placed a blue plaque on the site of Vane's former home in Hampstead.

Historian James Kendall Hosmer wrote in 1908 that Vane's "heroic life and death, his services to Anglo-Saxon freedom, which make him a significant figure even to the present moment, may well be regarded as the most illustrious character who touches early New England history." He added that Vane's life strongly supported "American ideas" of government "of, by, and for the people."

American abolitionist Wendell Phillips called Vane "the noblest human being who ever walked the streets of yonder city." He believed Vane's ideas were far ahead of his time. Phillips said Vane's "ermine has no stain; no act of his needs explanation or apology."

Images for kids

-

Portrait by Sir Peter Lely

-

Sir Henry Vane the Elder, portrait by Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt

-

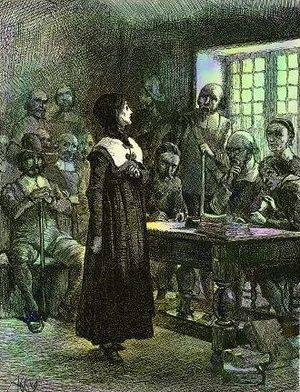

Engraving depicting the trial of Anne Hutchinson

-

Engraving depicting Roger Williams with the Narragansett Indians

-

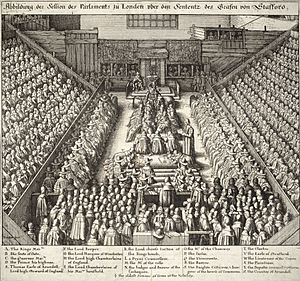

Engraving by Wenceslas Hollar depicting the trial of the Earl of Strafford

-

19th century depiction of the Westminster Assembly of Divines

-

Vane supported Oliver Cromwell during the Civil War, but fell out with him later.

-

Colonel Pride refusing admission to the Presbyterian members of the Long Parliament (Pride's Purge)

-

Cromwell dissolving Parliament on 20 April 1653

-

The gate to Carisbrook Castle, where Vane was imprisoned in 1656

-

General John Lambert

-

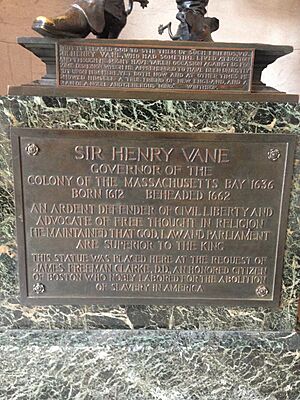

Statue in Boston Public Library

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |