Religious tolerance facts for kids

Religious toleration means allowing people to practice different religions, even if you don't agree with their beliefs. It's about respecting that others have different ways of thinking about faith. Throughout history, this idea has often been about how a main religion treats smaller groups with different beliefs.

This idea of toleration has grown over time. It now includes accepting people from different backgrounds, like those with different beliefs, cultures, or even LGBT individuals. It's closely linked to the idea of human rights, which are basic rights for everyone.

Contents

- Ancient Times: Early Steps Towards Tolerance

- Buddhism: A Path of Unity

- Christianity: From Persecution to Acceptance

- Middle Ages: Early Ideas of Tolerance

- The Reformation: New Ideas on Freedom of Belief

- The Enlightenment: New Ways of Thinking

- Milton: Freedom of Conscience

- Rudolph II: Tolerance in Bohemia

- Tolerance in the American Colonies

- Spinoza: Freedom to Think

- Locke: Many Religions, Less Unrest

- Bayle: Tolerance Prevents Trouble

- Toleration Act 1688: English Freedom of Worship

- Voltaire: All Humans Are Brothers

- Lessing: Wisdom and Understanding

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

- The First Amendment to the United States Constitution

- The 1800s: More Progress=

- The 1900s: Global Recognition=

- Hinduism: Truth Has Many Names

- Islam: Respecting People of the Book

- Judaism: A History of Persecution and Resilience

- Modern Ideas and Challenges

- See also

- Sources

Ancient Times: Early Steps Towards Tolerance

Long ago, some empires showed religious tolerance. The Achaemenid Empire in Persia was known for this. Its leader, Cyrus the Great, even helped people rebuild their holy places. The Old Testament says Cyrus allowed the Jewish people to return to their homeland after being held captive.

The ancient city of Alexandria in Egypt was also a place where different groups lived together peacefully. It had large communities of Jewish, Greek, and Egyptian people.

Before Christianity became the main religion of the Roman Empire, the Romans often let conquered people keep their own gods. However, Christians were sometimes treated badly because they refused to worship the Roman gods or the emperor. Other groups, like the Druids and followers of Isis, also faced problems.

In 311 CE, a Roman Emperor named Galerius made a rule, called an edict, that allowed Christians to practice their religion freely.

Later, around 623 CE, a Christian group from the Sinai Peninsula asked Mohammed, the founder of Islam, for protection. He gave them a special letter, known as the Ashtiname of Muhammad, promising to protect their monastery and their Christian faith.

Buddhism: A Path of Unity

King Ashoka the Great, a Buddhist ruler in ancient India (269–231 BCE), made rules called the Edicts of Ashoka. These rules promoted kindness and religious tolerance. He believed that no one should think their religion is better than others. Instead, people should try to find unity and learn from other faiths.

However, even in Buddhism, there have been times when tolerance was a challenge. Some people have discussed if there was intolerance among Buddhists in places like Sri Lanka and Myanmar, especially towards Muslims.

Christianity: From Persecution to Acceptance

The Christian Bible, in books like Exodus and Leviticus, talks about treating strangers well. For example, Exodus 22:21 says: "You must not bother or treat badly a stranger, because you were strangers in the land of Egypt." These ideas are often used to encourage kindness and tolerance towards people who are different.

The New Testament has a story called the Parable of the Tares. It talks about not pulling up weeds (bad plants) from a field until harvest time, so you don't accidentally pull up the good wheat too. This story has been used to argue that people with different religious ideas should be allowed to exist alongside others, and that God will judge them in the end, not humans.

Roger Williams, an early American thinker, used this story to support the idea that the government should allow all religions. He believed it was God's job to judge, not people's. This led him to believe in a "wall of separation between church and state" – meaning the government and religion should be kept separate.

Middle Ages: Early Ideas of Tolerance

In the Middle Ages, there were some examples of groups being tolerated. The idea of tolerantia (tolerance) was discussed in religious and legal writings. However, people with different beliefs, like the Cathari and Hussites, were often treated badly. The idea of tolerance as a government rule didn't really appear until the 1500s.

Church Rules and Jewish Tolerance

For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church often did not tolerate other faiths. A famous rule from 1302, called Unam sanctam, stated that everyone needed to be part of the Catholic Church to be saved.

Despite this, there were times when Jewish people found safety. In Poland in 1264, the Statute of Kalisz gave Jews freedom to practice their religion.

In 1348, during the Black Death plague, Pope Clement VI asked Catholics not to harm Jews, who were often blamed for the disease. He pointed out that Jews also died from the plague, and it spread where there were no Jews. He even protected Jews in his own city of Avignon.

Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522), a German scholar, spoke out against taking away religious books from Jews to force them to convert.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a relatively safe place for Jews in the Middle Ages. The Statute of Kalisz in 1264 protected their safety, freedom of religion, and trade. By the mid-1500s, about 80% of the world's Jewish population lived there. Jewish worship was officially allowed, and their property was protected.

Paulus Vladimiri: Peace Among Nations

Paulus Vladimiri (c. 1370–1435) was a Polish scholar who argued that different nations, even pagan and Christian ones, could live together peacefully. He criticized wars against non-Christian people and believed in mutual respect among nations. He was an early supporter of human rights.

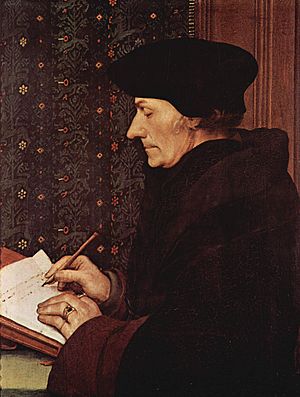

Erasmus: Gentle Disagreements

Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) was a Dutch thinker who helped lay the groundwork for religious tolerance. He believed that people discussing religious ideas should be calm and gentle, so that the truth could be found more easily. While he didn't stop all punishment for different beliefs, he usually argued against the death penalty. He famously said, "It is better to cure a sick man than to kill him."

Thomas More: A Vision of Utopia

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), an English author, wrote a book called Utopia (1516). In this imagined perfect world, people could have many different religious beliefs without being treated badly by the government. However, it's not clear if More thought real-life society should be exactly like Utopia. In his own life, he approved of actions against those who challenged the Catholic faith in England.

The Reformation: New Ideas on Freedom of Belief

During the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther (1483–1546) refused to change his beliefs at the Diet of Worms in 1521. He said he was following his own freedom of conscience. Luther believed that faith was a gift from God and couldn't be forced. He thought that different beliefs should be met with discussion, not violence. He said, "Heretics should not be overcome with fire, but with written sermons."

However, Luther still believed that governments could remove people with different beliefs if they caused public problems. Groups like the Anabaptists, who refused to take oaths or join the military, were sometimes seen as a threat and were treated badly by both Catholic and Protestant leaders. But many Anabaptists bravely stood up for freedom of conscience, which helped the idea of tolerance grow.

Castellio: Don't Kill for Beliefs

Sebastian Castellio (1515–1563) was a French Protestant who strongly criticized the execution of people for their beliefs. He wrote that if someone argues with ideas, they should be answered with ideas. Castellio believed that people could live peacefully together if they controlled their intolerance. He famously said, "To kill a man is not to protect a doctrine, but it is to kill a man."

Bodin: Respecting All Faiths

Jean Bodin (1530–1596) was a French Catholic thinker. He wrote a book called The Colloqium of the Seven where seven men from different religious and philosophical backgrounds talk about truth. They all agree to live with mutual respect and tolerance.

Montaigne: Don't Be Too Sure

Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) was a French Catholic writer. He believed that because we can't be absolutely sure about everything, we shouldn't be too quick to judge others' views. He wrote, "It is putting a very high value on one's guesses, to have a man roasted alive because of them...To kill people, there must be sharp and brilliant clarity."

Edict of Torda: A Big Step in Hungary

In 1568, King John II Sigismund of Hungary issued the Edict of Torda. This rule allowed religious tolerance for most Christian groups, which was a huge achievement for that time in Europe.

Maximilian II: Tolerance in Austria

In 1571, Emperor Maximilian II allowed religious tolerance for nobles and their workers in Lower Austria.

The Warsaw Confederation: Freedom in Poland

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had a long history of religious freedom. In 1573, the Warsaw Confederation officially recognized complete freedom of religion. This was during a time when religious persecution was common in other parts of Europe. This agreement was signed by representatives of all major religions in Poland and Lithuania, promising mutual support and tolerance.

Edict of Nantes: Peace in France

The Edict of Nantes, signed by Henry IV of France in 1598, gave important rights to Protestants (like the Huguenots) in France, even though Catholicism was the main religion. This rule helped end the religious wars in France by separating civil law from religious rights. It allowed Protestants to work in any field and bring their problems directly to the king.

However, this edict was later cancelled in 1685 by King Louis XIV, leading to more problems for Protestants. It wasn't until 1787 that King Louis XVI signed the Edict of Versailles, which restored rights for Protestants.

The Enlightenment: New Ways of Thinking

Starting in the 1600s, during the Enlightenment, thinkers and leaders began to develop new ideas about religious tolerance and create laws based on them. They started to see a difference between "civil tolerance" (how the government treats different religions) and "church tolerance" (how much diversity a church allows within itself).

Milton: Freedom of Conscience

John Milton (1608–1674), an English poet, argued for "the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties." He believed that the government should not force people's beliefs, but instead let the power of religious teachings persuade them.

Rudolph II: Tolerance in Bohemia

In 1609, Rudolph II made a rule allowing religious tolerance in Bohemia.

Tolerance in the American Colonies

In 1636, Roger Williams founded Rhode Island with the idea that people should obey the government only in "civil things," not religious ones. He wanted complete religious freedom, which was very rare at the time. In 1663, the colony received a charter guaranteeing full religious tolerance.

Also in 1636, Thomas Hooker founded Connecticut with a democratic government and unlimited freedom of conscience. Like Martin Luther, he believed that faith couldn't be forced.

In 1649, Maryland passed the Maryland Toleration Act. This law required religious tolerance for Christians who believed in the Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). It was the first law of its kind in the British colonies of North America. The Calvert family, who founded Maryland, wanted to protect Catholic settlers and other groups who didn't follow the main Anglican Church of England.

In 1657, New Amsterdam (now New York City), which was run by Dutch Calvinists, granted religious tolerance to Jews who had fled persecution in Brazil.

In Pennsylvania, William Penn and the Quakers made religious tolerance a key part of their government. The 1701 Charter of Privileges allowed religious freedom for all who believed in one God, and Christians could hold government positions.

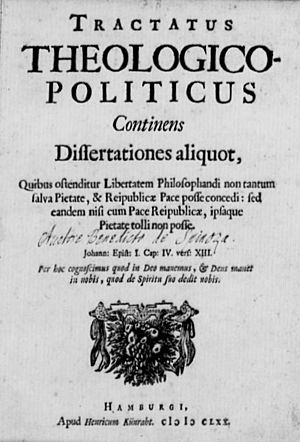

Spinoza: Freedom to Think

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) was a Dutch Jewish philosopher. In his book, Theological-Political Treatise (1670), he argued that freedom to think and discuss ideas was good for society and for religion. He believed that everyone should be able to understand and interpret religious ideas in their own way.

Locke: Many Religions, Less Unrest

English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) wrote A Letter Concerning Toleration in 1689. He believed that having many different religious groups could actually prevent civil unrest, rather than cause it. He thought that problems arose when governments tried to stop people from practicing different religions. However, Locke did not extend tolerance to Catholics (for political reasons) or to atheists, as he believed they couldn't be trusted with oaths.

Bayle: Tolerance Prevents Trouble

Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) was a French Protestant scholar. He argued strongly for religious tolerance. He pointed out that every church thinks it's the right one, so if one church persecutes another, it might be persecuting the true church. Bayle believed that problems came from a lack of tolerance, not from having many religions. He said, "All the trouble comes not from Tolerance, but from the lack of it."

Toleration Act 1688: English Freedom of Worship

The Toleration Act 1688 in England allowed freedom of worship for Protestants who didn't follow the official Church of England (called Nonconformists). They could have their own churches and teachers. However, this act did not apply to Catholics or those who didn't believe in the Trinity, and it still kept some limits on Nonconformists, like not allowing them to hold political office.

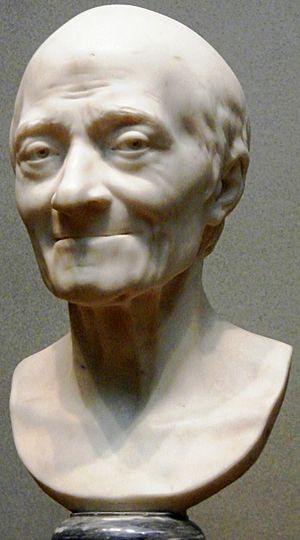

Voltaire: All Humans Are Brothers

Voltaire (1694–1778), a famous French writer and philosopher, published his Treatise on Toleration in 1763. He argued that Christians should tolerate each other, and went further, saying, "I say that we should regard all men as our brothers." He asked, "What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?"

Lessing: Wisdom and Understanding

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781), a German writer, believed in a "Christianity of Reason," where human understanding would grow through discussion and different ideas. His plays, like "Nathan der Weise", are famous for promoting social and religious tolerance. This play includes a story about three rings, where three sons represent Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Each son believes he has the one true ring, but only God can truly judge which is correct.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), created during the French Revolution, states in Article 10: "No-one shall be bothered for his opinions, even religious ones, as long as their practice does not disturb public order as established by the law." This was a big step for religious freedom in France.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution, added in 1791, says: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..." This means the government cannot create an official religion or stop people from practicing their own.

In 1802, Thomas Jefferson wrote about this, saying it built "a wall of separation between Church & State."

The 1800s: More Progress=

Laws for religious tolerance continued to develop, and thinkers kept discussing why it was important.

Roman Catholic Relief Act

In 1829, the British Parliament passed the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829. This law removed the last of the rules that limited the rights of Catholic citizens in the United Kingdom.

In 1882, French historian Ernest Renan suggested that a nation is built on "a spiritual principle" of shared memories, not just a common religion or language. This meant that people of any religion could be full members of a nation. He said, "You can be French, English, German, yet Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, or practicing no religion."

The 1900s: Global Recognition=

In 1965, the Catholic Vatican II Council issued a statement called Dignitatis humanae (Religious Freedom). It declared that all people must have the right to religious freedom.

In 1986, the first World Day of Prayer for Peace was held in Assisi, Italy. Representatives from 120 different religions came together to pray for peace.

In 1988, Mikhail Gorbachev, the leader of the Soviet Union, promised more religious tolerance, which was a big change for the country.

Hinduism: Truth Has Many Names

The ancient Hindu scripture Rigveda says, Ekam Sath Viprah Bahudha Vadanti, which means "The truth is One, but wise people call it by different Names." This idea of accepting many paths to truth is central to Hinduism. India, a country with a Hindu majority, chose to be a secular country, meaning it respects all religions.

Hinduism has a long history of accepting different religions. Christianity arrived in India in the first century CE. Judaism came after the Jewish temple was destroyed in 70 CE. Author Nathan Katz noted that India is the only country where Jews have not been persecuted. Zoroastrians from Persia (now Iran) also found safety in India in the 7th century. They are known as Parsis and have become a successful community in India.

Islam: Respecting People of the Book

The Quran, the holy book of Islam, teaches its followers to tolerate "the people of all faiths and communities" and let them keep their dignity, as long as they follow basic laws.

Under Islamic law, Jews and Christians were often given a special status called dhimmis. This meant they had certain protections and could practice their religion, though they had some restrictions and paid extra taxes.

In the Ottoman Empire, Jewish communities were protected. Sultan Beyazid II even invited Jews who were forced out of Catholic Spain and Portugal to settle in his empire.

Judaism: A History of Persecution and Resilience

Jews have faced many challenges throughout history. They were treated badly and deported from the Neo-Babylonian Empire as early as 605 BCE. During the Spanish Inquisition, many Jews were forced to convert to Christianity or leave Spain. Those who converted but secretly practiced Judaism were also targeted.

Jews have often been blamed unfairly for problems, like during the Black Death Persecutions and in many Pogroms in the Russian Empire. The ideas of Nazism before and during World War II led to the Holocaust, where six million Jews were murdered. After the war, Jews also faced problems in the Soviet Union.

Modern Ideas and Challenges

Today, the idea of tolerance is seen as a key part of human rights. It means that as long as no one is harmed or their basic rights are violated, the government should allow people to live as they choose, even if others disagree with their choices.

However, there are still challenges. For example, some people ask: "Should we tolerate those who are intolerant?" This means, if a group doesn't believe in tolerance for others, should a tolerant society still tolerate them? Thinkers like Karl Popper and John Rawls have discussed this. Rawls suggests that an intolerant group should be tolerated unless they directly threaten the safety of others.

Another question is about how much criticism is allowed in a tolerant society. Some argue that minorities must accept criticism as part of freedom of speech. There are also discussions about whether a country is a "tolerant secular" nation (where religion and government are separate) or a "tolerant religious" nation (where religious ideas are more involved in politics).

Some people, like Sam Harris, argue that society should not tolerate religious beliefs that promote violence or are clearly wrong about facts.

See also

In Spanish: Tolerancia religiosa para niños

In Spanish: Tolerancia religiosa para niños

- Anekantavada

- Freedom From Religion Foundation

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of religion by country

- History of Christian thought on persecution and tolerance

- Islam and other religions

- Multifaith space

- Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance

- Religious discrimination

- Religious intolerance

- Religious persecution

- Religious pluralism

- Secular state

- Separation of church and state

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good?, 24, UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good?, 24, UNESCO.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |