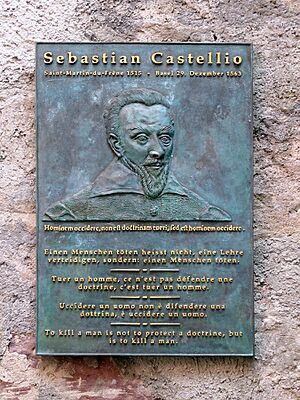

Sebastian Castellio facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sebastian Castellio

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1515 |

| Died | 29 December 1563 (aged 47–48) Basel, Swiss Confederation

|

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Preacher, professor, theologian, translator |

|

Notable work

|

De haereticis, an sint persequendi |

| Theological work | |

| Notable ideas | Freedom of thought |

Sebastian Castellio (born 1515, died 1563) was a French preacher and religious thinker. He was one of the first people to strongly support religious toleration, which means respecting different religious beliefs. He also believed in freedom of thought and conscience.

Contents

Who Was Sebastian Castellio?

Castellio was deeply affected by seeing people punished for their beliefs in Lyon. At age 24, he decided to follow the ideas of the Protestant Reformation. In 1540, after seeing early Protestants face harsh treatment, he left Lyon. He then became a missionary, sharing Protestant ideas with others.

Castellio's Early Work

In 1543, a serious illness spread through Geneva. Sebastian Castellio was one of the few religious leaders who visited the sick and comforted those who were dying. Even though John Calvin, another important leader, also visited the sick, many other ministers in Geneva did not.

Because of his excellent work, the Geneva City Council wanted Castellio to become a permanent preacher. However, in 1544, Calvin started to work against him. At that time, Castellio was excited to translate the Bible into French. He asked Calvin for his support, but Calvin had already supported his cousin's French Bible translation. So, Castellio's request was turned down.

Calvin wrote to a friend about it: "Just listen to Sebastian's strange plan, which makes me smile and also angry. Three days ago he asked me for permission to publish his New Testament translation."

Disagreements with Calvin

Castellio and Calvin's disagreements grew. During a public meeting, Castellio said that religious leaders should stop punishing people who had different ideas about the Bible. He believed leaders should follow the same rules as everyone else.

Soon after, Calvin accused Castellio of "undermining the prestige of the clergy." Castellio had to quit his job as a school principal and asked to leave his preaching role. He asked for a signed letter explaining why he left. The letter stated: "No one should misunderstand why Sebastian Castellio left. We all declare that he willingly resigned as school principal. He performed his duties so well that we thought he was worthy to be one of our preachers. If things didn't work out, it's not because Castellio did anything wrong, but for the reasons mentioned before."

Years of Hardship

Castellio, who was once a respected school principal, became homeless and very poor. The next few years were very difficult for him. Even though he was one of the smartest people of his time, he sometimes had to beg for food. He lived in extreme poverty with his eight family members, relying on strangers to survive.

His struggles gained sympathy from others. Montaigne, a famous writer, said it was sad that such a helpful person like Castellio faced such hard times. He added that many people would have helped Castellio if they had known he was in need.

Many people were likely afraid to help Castellio because they feared Calvin's disapproval. Castellio's life involved begging, digging ditches for food, and checking texts for a print shop in Basel. He also worked as a private tutor. He translated thousands of pages from Greek, Hebrew, and Latin into French and German.

Castellio's Important Ideas

Castellio was seen as the person to continue the work of Desiderius Erasmus. Erasmus wanted to bring different Christian groups together. Castellio predicted that if Christians did not learn to be tolerant and use love and reason instead of violence, there could be religious wars. He believed Christians should truly follow Christ, not just bitter, divided ideas.

His writings were shared widely for a while, but then they were forgotten. John Locke, another famous thinker, wanted them published. However, at that time, it was a crime punishable by death to even own copies of Castellio's writings or texts about the Servetus controversy. So, Locke's friends convinced him to publish similar ideas under his own name. Castellio's writings were remembered by important religious scholars and historians like Gottfried Arnold and Roger Williams.

In 1551, his Latin translation of the Bible was published. In 1555, his French translation of the Bible, known as the Castellio Bible, was also published.

Conflict Over Religious Freedom

Castellio's situation slowly got better. In August 1553, he earned a Master of Arts degree from the University of Basel. He also got an important teaching job. However, in October 1553, a doctor named Michael Servetus was executed in Geneva. He was accused of going against Christian teachings, especially about the Trinity.

Many Protestant leaders approved of this execution. Philip Melanchthon wrote to Calvin: "The Church owes you thanks now and forever. Your leaders were right to punish this disrespectful man after a fair trial." However, many other scholars, like David Joris, were very upset about Servetus's execution. Castellio was especially angry, calling it a clear murder by Calvin. He said Calvin's "hands were dripping with the blood of Servetus."

Castellio's Defense of Tolerance

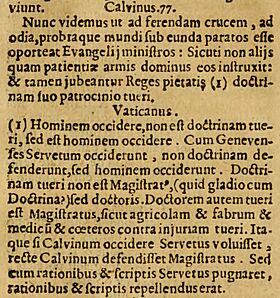

In February 1554, Calvin published a book defending his actions. It was called Defense of the orthodox faith in the sacred Trinity. In it, he argued that Servetus's execution was right because he disagreed with traditional Christian beliefs.

Three months later, Castellio wrote a large part of a pamphlet called Treatise on Heretics. It was published under the name Martinus Bellius and printed by Johannes Oporinus. It is believed that Lelio Sozzini and Celio Secondo Curione also helped write it.

About Servetus's execution, Castellio wrote: "When Servetus fought with ideas and writings, he should have been answered with ideas and writings." He used the words of early Church leaders like Augustine to support freedom of thought. He even used Calvin's own words from when Calvin was being treated unfairly by the Catholic Church: "It is not Christian to use weapons against those who have been removed from the Church, and to deny them rights common to all people."

Castellio asked, "Who is a heretic?" He concluded, "I can find no other answer than that we are all heretics in the eyes of those who do not share our views."

Castellio's book Advice to a desolate France is seen as a call for peace.

Castellio also greatly helped the idea of limited government. He strongly argued for the separation of church and state. This means that the government and religious institutions should be separate. He was against the idea of a theocracy, where religious leaders control the government.

He believed that no one has the right to control another person's thoughts. He stated that authorities should "have no concern with matters of opinion." He concluded: "We can live together peacefully only when we control our intolerance. Even though there will always be differences of opinion, we can at least come to general understandings, love one another, and live in peace, until the day we all share the same faith."

Castellio's Death

Castellio died in Basel in 1563 and was buried in a noble family's tomb. Sadly, his enemies later dug up his body, burned it, and scattered the ashes. Some of his students built a monument to remember him. This monument was later accidentally destroyed, but its inscription (the words written on it) is still preserved.

Castellio's Writings

- Dialogi Sacri. Geneva 1542, also a much expanded version, Basel 1545

- Biblia interprete Sebastiano Castalione. Basel 1551

- Treatise on Heretics. Basel 1554

- Against Calvin's Booklet. Basel 1554 (first edition 1612)

- Castellio Bible. Basel 1555

- De arte dubitandi.

- Advice to a desolate France. 1562

- De Imitatione Christi. 1563