Roger Williams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roger Williams

|

|

|---|---|

Roger Williams (1872)

|

|

| 9th President of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1654–1657 |

|

| Preceded by | Nicholas Easton |

| Succeeded by | Benedict Arnold |

| Chief Officer of Providence and Warwick | |

| In office 1644–1647 |

|

| Preceded by | Himself (as Governor) |

| Succeeded by | John Coggeshall (as President) |

| Governor of Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1636–1644 |

|

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Chief Officer) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1599 London, England |

| Died | between 21 January and 15 March 1683 (aged 79) Providence, Rhode Island, English America |

| Spouse | Mary Bernard |

| Children | 12 |

| Education | Pembroke College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Minister, statesman, author |

| Signature | |

Roger Williams (born around 1603, died 1683) was an English minister and writer. He founded Providence Plantations, which later became the U.S. state of Rhode Island. Williams strongly believed in religious freedom and the idea of keeping church and government separate. He also worked for fair treatment of Native Americans.

Williams was forced to leave the Massachusetts Bay Colony by its Puritan leaders. In 1636, he started Providence Plantations as a safe place. He called it a place for "liberty of conscience", meaning people could believe what they wanted. In 1638, he helped start the First Baptist Church in America in Providence. Williams also learned Native American languages. He wrote the first English book about a native North American language.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Roger Williams was born in London, England, likely in 1603. We don't know the exact date. This is because his birth records were lost in the Great Fire of London. His father, James Williams, was a merchant tailor. His mother was Alice Pemberton.

When he was young, Williams had a religious experience. His father did not approve of this. As a teenager, he worked for Sir Edward Coke, a famous judge. Coke helped him get an education at Charterhouse School. Williams later went to Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he earned a degree in 1627.

Williams was very good with languages. He learned Latin, Hebrew, Greek, Dutch, and French early on. Years later, he taught Dutch and Native American languages to John Milton. In return, Milton helped him practice Hebrew.

Williams became a minister in the Church of England. However, he became a Puritan at Cambridge. This meant he could not advance in the Anglican church. After college, he worked as a chaplain for Sir William Masham, 1st Baronet. In 1629, he married Mary Bernard. She was the daughter of a well-known Puritan preacher. Roger and Mary had six children, all born in America.

Williams knew that Puritan leaders planned to move to the New World. He did not join the first group of settlers. But he later decided he could not stay in England. He felt the Church of England was corrupt. By 1630, he believed in separating completely from it. On December 1, Williams and his wife sailed to Boston.

First Years in America

Arrival in Boston and Early Beliefs

On February 5, 1631, Williams' ship arrived near Boston. The church in Boston offered him a job. But Williams turned it down. He said it was "an unseparated church." This meant it was not fully separate from the Church of England.

Williams also believed that government leaders should not punish people for their religious beliefs. He felt people should be free to follow their own conscience in religious matters. These ideas became very important in his later work.

Time in Salem and Plymouth

As a Separatist, Williams believed the Church of England was too corrupt. He felt people needed to start a new church. The Salem church was also Separatist. They invited him to be their teacher. But leaders in Boston protested. So Salem took back its offer.

Williams moved to Plymouth Colony in 1631. He helped the minister there. The colony's governor, William Bradford, said Williams' teachings were "well approved."

After a while, Williams felt the Plymouth church was also not separate enough from the Church of England. He also started to question the colonial land charters. He believed the land should be bought from the Native Americans first. Governor Bradford wrote that Williams developed "strange opinions."

In 1632, Williams wrote a paper criticizing the King's charters. He said the King had no right to claim land without buying it from Native Americans. He moved back to Salem in 1633.

Conflict and Exile

The leaders of Massachusetts Bay were not happy about Williams' return. In December 1633, they called him to court in Boston. He had to defend his paper about the King and the charter. The issue was settled, and the paper was likely destroyed.

In August 1634, Williams became the acting pastor of the Salem church. In March 1635, he was again ordered to appear in court. He was called again in July for his "erroneous" and "dangerous opinions." The court finally ordered him removed from his church job.

The town of Salem wanted more land. The court refused unless Salem removed Williams. The Salem church felt this was unfair. Support for Williams weakened. He left the church and met with followers at his home.

In October 1635, the court tried Williams. They found him guilty of spreading "dangerous opinions." They ordered him to be banished. The order was delayed because he was sick and winter was coming. He was allowed to stay if he stopped teaching his ideas. He did not stop. In January 1636, he left during a snowstorm. He traveled 55 miles to Raynham, Massachusetts. The local Wampanoag people gave him shelter. Their leader, Massasoit, hosted Williams for three months.

Founding Providence

In spring 1636, Williams and others from Salem started a new settlement. It was on land he bought from Massasoit. But Plymouth Colony said this land was theirs. They worried Williams' presence would upset Massachusetts Bay.

So, Williams and Thomas Angell crossed the Seekonk River. They looked for a new place. Native Americans greeted them with "What cheer, Netop" (Hello, friend). They continued along the Providence River. They found a good spot with a cove and fresh spring. Williams bought this land from sachems Canonicus and Miantonomi.

Williams and his followers built a new town. They believed God's "divine providence" had led them there. So, they named the settlement "Providence."

Williams wanted Providence to be a safe place for people with different beliefs. Many people seeking religious freedom came there. From the start, the town was governed by a vote of the heads of households. But this government only dealt with "civil things," not religious matters. Newcomers could become citizens by a majority vote. In 1640, 39 men signed an agreement. It stated their goal to "hold forth liberty of conscience."

This made Providence the first place in modern history where citizenship and religion were separate. It offered religious freedom and a separation of church and state. It also used the idea of majoritarian democracy, where the majority rules.

In 1637, Massachusetts banished followers of Anne Hutchinson. John Clarke was among them. Williams told him that Aquidneck (Rhode) Island could be bought from the Narragansetts. Williams helped Clarke and others buy the land. They started the settlement of Portsmouth. In 1638, some settlers from Portsmouth founded Newport on Aquidneck Island.

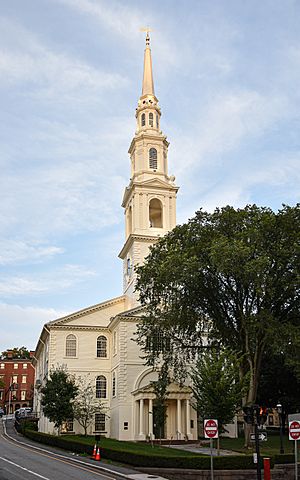

In 1638, Williams and about twelve others were baptized. They formed a church. Today, this church is known as the First Baptist Church in America.

Relations with Native Americans

The Pequot War started around this time. Massachusetts Bay asked Williams for help. He helped them, even though he was banished. He acted as their eyes and ears. He also convinced the Narragansetts not to join the Pequots. Instead, the Narragansetts allied with the colonists. They helped defeat the Pequots in 1637–38. This made the Narragansetts the most powerful Native American tribe in southern New England.

Williams became good friends with Native American tribes. He especially trusted the Narragansetts. He helped keep peace between Native Americans and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for almost 40 years. He did this by constantly talking and negotiating. He even offered himself as a hostage twice. This was to guarantee the safe return of a great leader from court.

Other New England colonies began to fear the Narragansetts. They also saw Rhode Island as an enemy. For the next 30 years, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth tried to weaken Rhode Island and the Narragansetts. In 1643, the neighboring colonies formed a military group called the United Colonies. They purposely left out the towns around Narragansett Bay. Because of this, Williams traveled to England to get a charter for the colony.

Securing the Colony's Charter

Williams arrived in London during the English Civil War. Puritans were in power there. He was able to get a charter for Providence Plantations in July 1644. This was despite strong opposition from Massachusetts.

A Key into the Language of America

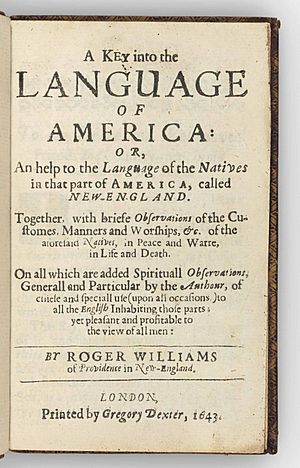

Williams' first published book helped him get the charter. It was called A Key into the Language of America. He published it in 1643 in London. The book was a phrase-book combined with notes about Native American life and culture. It helped people communicate with the Native Americans of New England. It covered everything from greetings to death customs.

This book was the first full study of a native North American language in English. It was very popular in England. Readers were curious about the people of the New World.

The Bloudy Tenent

After getting his charter, Williams published his most famous book. It was called The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience. This book caused a big stir. Many other books were written in response to it. Parliament even ordered all copies to be burned. But by then, Williams was already sailing back to New England. He arrived with his charter in September.

It took Williams several years to unite the settlements around Narragansett Bay. This was because of opposition from William Coddington. The four villages finally united in 1647. They formed the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Freedom of conscience was again declared. The colony became a safe place for people with different beliefs. This included Baptists, Quakers, and Jews.

However, there were still disagreements among the towns' leaders. Coddington did not like Williams. He also did not like being under the new charter government. So, Coddington sailed to England. He returned to Rhode Island in 1651 with his own special permission. This made him "Governor for Life" over Aquidneck and Conanicut Islands.

Because of this, Providence, Warwick, and Coddington's opponents sent Roger Williams and John Clarke to England. They wanted to cancel Coddington's special permission. Williams sold his trading post to pay for his trip. This trading post was his main source of income. Williams and Clarke succeeded in canceling Coddington's permission. Clarke stayed in England for ten more years to protect the colonists' interests. He also worked to get a new charter.

Williams returned to America in 1654. He was immediately elected the colony's president. He then served in many government jobs in both the town and the colony.

Views on Slavery

Williams did not write much about slavery. But he did not approve of people being enslaved forever. He generally did not object to capturing enemy fighters and enslaving them for a set time. He sometimes gained from this practice.

Williams thought about the fairness of slavery during his life. He wrote to Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop about how the Pequots were treated during the Pequot War (1636–1638). He asked Winthrop to stop the enslavement of Pequot women and children. He also asked the colonial army to spare them during the fighting.

In 1641, Massachusetts Bay Colony made laws allowing slavery. In response, Williams led Providence Plantations to pass a law in 1652. This law limited how long a person could be enslaved. It also tried to stop the import of enslaved Africans. The law said slavery should be for a limited time, like indentured servitude. It also said slavery should not pass down to children.

When Providence Plantations united with Aquidneck Island, people on Aquidneck Island refused this law. So, it did not take effect. Later in life, during King Philip's War, Williams' home was burned down. During the war, Williams and some Providence citizens helped sell captured Narragansetts and Wampanoag people.

King Philip's War and Death

King Philip's War (1675–1676) was a conflict between colonists and Native Americans. This included the Narragansett, with whom Williams had been friendly. Williams, even in his 70s, was chosen as captain of Providence's militia. On March 29, 1676, Narragansett warriors burned Providence. Williams' home was among the buildings destroyed.

Burial and Legacy

Roger Williams died between January 16 and March 16, 1683. He was buried on his own land. Fifty years later, his house fell into its cellar. The exact spot of his grave was forgotten.

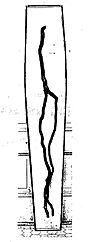

In 1860, people in Providence wanted to build a monument for him. They dug where they thought his remains were. They found only nails, teeth, and bone pieces. They also found an apple tree root. It seemed to follow the shape of a human body. The root looked like a spine, splitting at the hips, bending at the knees, and turning up at the feet.

The Rhode Island Historical Society has kept this tree root since 1860. It represents Rhode Island's founder. Since 2007, the root has been shown at the John Brown House.

The few remains found with the root were reburied in Prospect Terrace Park in 1939. They are at the base of a large stone monument.

Separation of Church and State

Williams strongly believed in the separation of church and state. He was sure that the government should not interfere with religious beliefs. He said the state should only deal with civil order. This means things like laws and justice, not religious beliefs. He believed the government should not enforce the "first Table" of the Ten Commandments. These are the commandments about a person's relationship with God. Williams thought the state should only focus on commandments about how people treat each other. These include not murdering, stealing, or lying.

Williams wrote about a "hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wilderness of the world." Thomas Jefferson later used a similar idea in his 1801 letter to the Danbury Baptists.

Williams thought that if the state supported religious beliefs, it was "forced worship." He said, "Forced worship stinks in God's nostrils." He believed that Constantine the Great was worse for Christianity than Nero. This is because Constantine's involvement of the state in religion corrupted Christianity.

Williams believed that the Bible's moral rules should guide government leaders. But he also noted that good, fair governments existed even where Christianity was not present. So, all governments needed to keep civil order and justice. But Williams decided that no government had the right to promote or stop any religious views. Most people at the time criticized his ideas. They thought his ideas would lead to chaos. Most believed that every nation needed its own national church. They also thought that people who disagreed should be forced to follow it.

Writings

Williams started his writing career with A Key into the Language of America (London, 1643). He wrote it during his first trip to England. His next book was Mr. Cotton's Letter lately Printed, Examined and Answered (London, 1644). His most famous work is The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (published in 1644). Some people consider it one of the best defenses of freedom of conscience.

Williams published The Bloody Tenent yet more Bloudy (London, 1652) during his second visit to England. This book repeated and expanded on his arguments from Bloudy Tenent.

Other books by Williams include:

- The Hireling Ministry None of Christ's (London, 1652)

- Experiments of Spiritual Life and Health, and their Preservatives (London, 1652)

- George Fox Digged out of his Burrowes (Boston, 1676) (This book discussed Quakerism, which Williams saw as different from his beliefs.)

His letters are collected in a volume called The Correspondence of Roger Williams.

Brown University's John Carter Brown Library has a 234-page book called the "Roger Williams Mystery Book." The edges of this book are filled with notes in a secret code. People believe Roger Williams wrote them. In 2012, a student cracked the code. It showed that Williams wrote the notes. The notes include parts of a geography text, a medical text, and 20 pages of original notes about infant baptism.

Legacy and Tributes

Williams defended Native Americans. He also said that Puritans were repeating the "evils" of the Anglican Church. He insisted that England pay Native Americans for their land. All these ideas put him at the center of many political discussions during his life.

He was seen as an important figure for religious liberty during the time of American independence. He greatly influenced the ideas of the Founding Fathers.

Tributes to Roger Williams

Many places and things are named after Roger Williams:

- The 1936 commemorative Rhode Island Tercentenary half dollar coin.

- Roger Williams National Memorial, a park in downtown Providence. It was created in 1965.

- Roger Williams Park in Providence, Rhode Island, and the Roger Williams Park Zoo.

- Roger Williams University in Bristol, Rhode Island.

- Roger Williams Dining Hall at the University of Rhode Island.

- Roger Williams Inn at the American Baptists' Green Lake Conference Center.

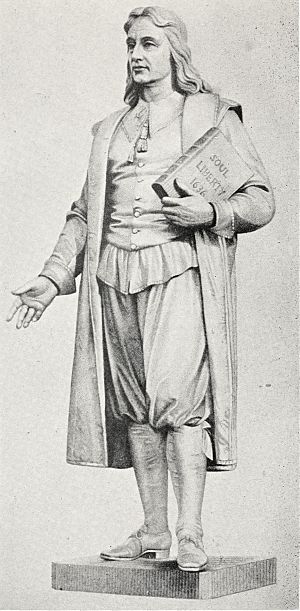

- Rhode Island's statue in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol. It was added in 1872.

- A picture of him on the International Monument to the Reformation in Geneva.

- Roger Williams Middle School, a public school in Providence.

- Pembroke College in Brown University was named after Williams' college.

Slate Rock

Slate Rock was a large boulder on the west shore of the Seekonk River. It was once a very important historical landmark in Providence. People believed it was the spot where the Narragansetts greeted Williams with "What cheer, netop?" City workers accidentally blew up the historic rock in 1877. They used too much dynamite while trying to uncover a buried part of the stone. A memorial in Roger Williams Square now marks the location.

Notable Descendants

Some famous people who are descendants of Roger Williams include:

- Senator Nelson W. Aldrich

- Gail Borden

- Julia Ward Howe

- Governor Sarah Palin

- Michelle Phillips (singer, actress)

- Vice President Nelson Rockefeller

- David Rockefeller

See also

In Spanish: Roger Williams para niños

In Spanish: Roger Williams para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |