Massachusetts Bay Colony facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Massachusetts Bay Colony

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1628–1691 Part of Dominion of New England, 1686–1689 |

|||||||||

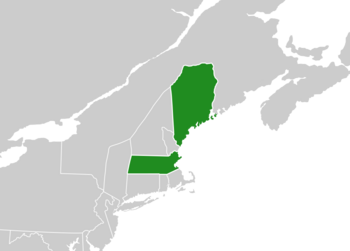

Map of the Massachusetts Bay Colony c. 1690

|

|||||||||

| Status | Disestablished | ||||||||

| Capital | Salem, Charlestown, Boston | ||||||||

| Common languages | English, Massachusett, Mi'kmaq | ||||||||

| Religion | Congregationalism (official) Puritanism | ||||||||

| Government | Self-governing colony | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

|

• 1629–1631

|

John Endecott (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1679–1692

|

Simon Bradstreet (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Great and General Court or Assembly of Massachusetts Bay | ||||||||

|

• Upper House (de facto)

|

Council of Assistants | ||||||||

|

• Lower House (de facto)

|

Assembly | ||||||||

| Historical era | |||||||||

|

• Council for New England land grant

|

1628 | ||||||||

|

• Charter issued

|

1629 | ||||||||

|

• New England Confederation formed

|

1643 | ||||||||

|

• Revocation of the Royal Charter

|

1684 | ||||||||

|

• Dominion of New England established

|

1686 | ||||||||

|

• Dominion dissolved

|

1689 | ||||||||

|

• Massachusetts Charter for the Province of Massachusetts Bay

|

1691 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished, reorganized as the Province of Massachusetts Bay

|

1691 | ||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an important English settlement in North America. It existed from 1628 to 1691. Located on the east coast around Massachusetts Bay, it was one of several colonies in New England. Its first towns were Salem and Boston. Over time, the colony grew to include parts of what are now Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Connecticut.

The colony was started by the Massachusetts Bay Company. Many of its founders were Puritans, a religious group seeking freedom to practice their faith. About 20,000 Puritans moved to New England in the 1630s. The colony's leaders were deeply guided by Puritan beliefs. Only church members could vote for governors. This meant they were not very welcoming to other religions. The colony also had enslaved people, making it the first in New England to do so.

At first, colonists had good relations with local Native American tribes. However, they later fought in conflicts like the Pequot War (1636–1638) and King Philip's War (1675–1678). After these wars, many Native American groups in southern New England made peace or faced difficult consequences.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony became very successful economically. It traded with England, Mexico, and the West Indies. They used English money, Spanish "pieces of eight", and wampum for trade. In 1652, the colony even started making its own coins, like the famous pine tree shillings.

Over time, disagreements grew between the colony and England. In 1684, England took away the colony's founding document, called its charter. King James II then created the Dominion of New England to control the colonies more tightly. But this Dominion ended after a big change in England's government in 1688. In 1691, a new charter created the Province of Massachusetts Bay. This new province included the old Massachusetts Bay lands, Plymouth Colony, and islands like Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard. This happened around the time of the difficult witch trials in Salem Village.

Contents

- The Massachusetts Bay Colony: A Puritan Story

- Life in the Colony

- Government in the Colony

- Economy and Trade in Early Massachusetts

- People and Places

- See also

The Massachusetts Bay Colony: A Puritan Story

Before Europeans arrived, many Native American tribes lived around Massachusetts Bay. These included the Massachusetts, Nausets, and Wampanoags. Other tribes like the Pennacooks and Nipmucs lived further inland. They used the land for farming and hunting. Sadly, a terrible sickness greatly reduced their population before the colonists came.

Early European Exploration

In the early 1600s, explorers like Samuel de Champlain and John Smith mapped the New England coast. In 1606, King James I of England allowed two companies to start colonies in North America. One company, the London Company, founded Jamestown. The other, the Plymouth Company, tried to settle in Maine in 1607. This settlement, called the Sagadahoc Colony, failed after just one year. For a while, people stopped trying to build permanent towns in New England. However, English ships still visited for fishing and trading with Native Americans.

The Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony

In December 1620, a group of English Separatists, known as the "Pilgrims", arrived. They founded Plymouth Colony just south of Massachusetts Bay. They sought religious freedom and a new way of life. The Pilgrims faced many challenges but eventually succeeded. Plymouth Colony remained separate until it joined Massachusetts Bay in 1691.

Other Early Settlements

There were other attempts to create colonies in the area. In 1623 and 1624, settlements were tried at Weymouth, Massachusetts. These early efforts, like Thomas Weston's Wessagusset Colony, often failed quickly. However, some families stayed and formed the oldest permanent settlement in what became Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The Cape Ann Fishing Village

In 1623, a small fishing village was started at Cape Ann. It was overseen by the Dorchester Company. This company was supported by Puritan minister John White. The Cape Ann settlement was not profitable. By 1625, its financial support ended. Some settlers, like Roger Conant, moved south. They established a new settlement near the Naumkeag tribe village, which later became Salem.

Founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Archbishop William Laud was a key advisor to King Charles I. He wanted everyone in England to follow the Anglican Church. Many Puritans felt persecuted and decided to leave England. They believed they could not practice their religion freely under King Charles.

A New Charter and a New Home

John White continued to seek support for a new colony. In 1628, a new group of investors received a land grant. This grant covered land between the Charles River and Merrimack River. The company was called "The New England Company for a Plantation in Massachusetts Bay." They chose Matthew Cradock as their first governor.

In 1628, the company sent about 100 settlers to join Roger Conant. They were led by John Endecott. The next year, the settlement was renamed Salem. Another 300 settlers arrived, led by Rev. Francis Higginson. The first winters were very hard, with many colonists dying from hunger and sickness.

The company leaders wanted a royal charter from the King. This would make their land claims more secure. King Charles granted the new charter on March 4, 1629. This charter officially created the English colony at Massachusetts. It named Endecott as governor.

A special part of this charter was missing: it didn't say where the annual meetings should be held. This allowed the company leaders to move their government to the colony itself. This was a very important decision. It meant the Massachusetts Bay Colony could govern itself more independently. This helped the settlers maintain their Puritan religious practices. The charter lasted for 55 years.

Challenges and Changes

Later, King Charles II took away the charter in 1684. He wanted more control over the colonies. England also passed laws called the Navigation Acts. These laws tried to stop colonists from trading with anyone but England. The colonists often ignored these laws. This led to more tension with the King.

The colony claimed land all the way to the Pacific Ocean. However, they only truly controlled land up to the Connecticut River valley. Other colonies, like New Netherland (Dutch), also claimed some of these lands.

Colonial Life and Growth

In April 1630, a group of ships, known as the Winthrop Fleet, sailed from England. They carried over 700 colonists and Governor John Winthrop. Winthrop gave a famous speech called "City upon a Hill" during this journey.

Over the next ten years, about 20,000 Puritans moved from England to Massachusetts. This period is called the Great Migration. Many ministers came with their church members. These included John Cotton, Roger Williams, and Thomas Hooker. Religious disagreements and the need for more land led to new settlements. These became Connecticut Colony and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms in England (starting 1639) slowed migration. Many colonists even returned to England to fight. Massachusetts leaders supported the Parliamentary cause in England. The colony's economy grew in the 1640s. Industries like fur trading, lumber, fishing, and shipbuilding became important.

After King Charles II returned to the throne in 1660, tensions grew. Charles wanted more control over the colonies. Massachusetts resisted, refusing to allow the Church of England to be established. They also ignored the Navigation Acts, which limited their trade.

The New England colonies suffered greatly during King Philip's War (1675–76). Native American peoples fought against the colonists. Many lives were lost on both sides. After the war, most Native American groups in southern New England made peace treaties.

Confrontation with England

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was largely self-governing. It had its own elected officials and laws. Unlike other colonies, its government was based in America, not London. This made colonists feel very independent from England. They believed their lands were given to them by God.

England tried to enforce its laws, but the colonists often refused. Royal officials were sent to investigate. They wanted the colonies to connect more strongly with England. But New Englanders claimed the King had no right to interfere with their laws.

Only Puritans could vote in Massachusetts Bay. But the colony's population was growing, including many non-Puritans. This led to disagreements about the colony's future. Some wealthy merchants wanted more economic freedom. They felt the Puritan leaders were too strict.

England saw these divisions and tried to use them to gain control. The colony was accused of denying the King's authority. They were also criticized for coining their own money (the pine tree shilling) and ignoring trade laws. English merchants complained that the colonists were hurting their business.

Edward Randolph was sent to Boston to regulate the colony. He found a government that refused to follow royal demands. Randolph reported this to London. The King eventually threatened to take away the colony's charter.

Revocation of the Charter

Delegates from Massachusetts Bay went to London to negotiate. But they were not allowed to agree to any changes to the charter. This angered the English Lords of Trade. So, the King decided to revoke the charter in 1684.

This decision caused problems in the colony. There were disagreements between those who wanted to submit to the King and those who wanted to resist. The General Court decided to wait for the King to act. Their government continued to operate until 1686, when the charter was officially revoked.

Unifications and Restoration

In 1686, King James II of England combined Massachusetts with other New England colonies. This new larger colony was called the Dominion of New England. It was ruled by Sir Edmund Andros, who had a lot of power. The Dominion was very unpopular.

In April 1689, colonists arrested Andros after a major change in England's government. Massachusetts then tried to restart its old government. However, some people argued that this government was no longer legal.

In 1691, King William III issued a new charter. This charter created the Province of Massachusetts Bay. It combined Massachusetts Bay with Plymouth Colony, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and parts of what are now Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. This new charter also allowed non-Puritans to vote, which was a big change.

Life in the Colony

Life was often hard in the early years of the colony. Many colonists lived in simple homes. These included dugouts and huts made of wood and mud. Over time, houses improved. They began to have wooden siding and brick chimneys. Wealthier families added more rooms, creating homes similar to the saltbox style.

New arrivals often found that older towns were full. So, groups of families would ask the government for land to start new towns. These new towns were usually about 40 square miles. They were built close enough to other towns for defense and support. The leaders of these groups also had to buy the land from Native American tribes. This is how the colony expanded inland.

Land within a town was divided by agreement. Areas were set aside for farming, and some land was shared. Town centers were compact. They often had a tavern, a school, small shops, and a meeting house. The meeting house was the center of town life. It was used for church services and town meetings. Puritans did not celebrate holidays like Christmas. Town meetings were held yearly to elect representatives. Towns also had a village green for outdoor activities and military training.

Family Life and Education

Many early colonists moved from England with their families. People were expected to marry young and have children. Infant and childhood death rates were relatively low. If a husband or wife died, the surviving partner often remarried quickly. This was especially true if they had children who needed care. Older widowed parents often lived with their children.

Children were usually baptized in the meeting house within a week of birth. The father typically chose the child's name. Names were often reused within families, especially if an infant died.

Most children received some form of schooling. The colony's founders believed education was important for religious understanding. Towns were required to provide education. Teachers varied from local people with basic education to ministers who had studied at Harvard.

Government in the Colony

The way the colonial government worked changed over time. The Puritans created a government where only church members could participate. Ministers, however, were not allowed to hold government positions. Leaders like Winthrop and Dudley wanted to prevent different religious views. Many people were banished for their beliefs, including Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson. By the mid-1640s, the colony had over 20,000 people.

The charter gave the general court the power to elect officers and make laws. Its first meeting in North America was in October 1630. Only eight freemen attended. They formed the first council of assistants. They decided to elect the governor and deputy from among themselves.

In 1631, 116 more settlers became freemen. But most power stayed with the council of assistants. A law was passed saying only church members could become freemen and vote. This rule stayed until after the English Restoration. Later, towns began sending two representatives, called deputies, to discuss taxes.

In 1634, deputies demanded to see the charter. The assistants had kept it hidden. The deputies learned that the general court should make all laws. They also learned that all freemen should be members of the general court. Governor Winthrop said this was not practical with so many freemen. They agreed that the general court would have two deputies from each town. Dudley was elected governor. The general court kept powers like taxation and land distribution.

In 1642, a legal case led to a change in government structure. The council of assistants became an upper house of the general court. The general court voted in 1644 that the council of assistants and the general court would meet separately. Both groups had to agree for any law to pass.

Laws and Justice

In 1641, the colony formally adopted the Massachusetts Body of Liberties. This document contained 100 civil and criminal laws. These laws were based on rules found in the Bible. They formed the basis of colonial law until independence. Some ideas from these laws, like equal protection, were later included in the United States Constitution.

Massachusetts Bay was the first colony to create formal laws about slavery. These laws included rules for how enslaved people should be treated. Other laws protected married women, children, and people with mental disabilities from making financial decisions. The colony also had "poor laws" in 1693. These allowed communities to use the property of people with disabilities to help pay for their care.

Many everyday behaviors were regulated. For example, sleeping during church or playing cards on the Sabbath could lead to legal trouble. However, children, newcomers, and people with disabilities were often excused from punishment for minor offenses.

The council of assistants served as the highest court. They heard serious criminal cases and civil cases involving large sums of money. Lesser offenses were handled in county courts. Juries decided both facts and laws. Punishments included fines, whipping, and sitting in the stocks. The most serious crimes could result in banishment or execution.

New England Confederation

In 1643, Massachusetts Bay joined Plymouth Colony, Connecticut Colony, and New Haven Colony. They formed the New England Confederation. This was an alliance to help coordinate military and administrative matters. It was most active during King Philip's War in the 1670s.

Economy and Trade in Early Massachusetts

In the 1600s, the colony relied heavily on goods imported from England. Wealthy immigrants also invested in the colony. Some businesses quickly grew strong. These included shipbuilding, fishing, and the fur and lumber trades. By 1632, ships built in the colony were trading with other colonies and Europe. By 1660, the colony had about 200 merchant ships. By the end of the century, its shipyards built hundreds of ships each year.

Early on, ships mainly carried dried fish to places like Portugal and Spain. They would then pick up wine and oil for England. Finally, they would bring finished goods back to the colony. These trade routes became illegal after England passed the Navigation Acts in 1651. This meant many colonial merchants became smugglers. Colonial leaders, who were often merchants, opposed these new trade restrictions. In 1652, the colony even started making its own coins, like the Pine tree shilling.

The fur trade was not a huge part of the economy. This was because the colony's rivers did not connect well with Native American fur trappers. Timber, especially for ship masts, became very important. This was due to conflicts between England and the Dutch, which reduced England's own timber supplies.

The colony's economy depended on trade. Its land was not as good for large farms as colonies like Virginia. Fishing was so important that those involved in it were excused from taxes and military service. Larger towns had skilled craftsmen. Many income-generating activities, like spinning and weaving, happened in homes.

Goods were transported on roads that were often old Native American trails. Towns had to maintain their roads. Bridges were rare because they were expensive. Most river crossings were done by ferry.

The colonial government tried to control the economy. They sometimes set wages and prices, but these rules usually did not last long. Trades like shoemaking and barrel-making (coopering) formed guilds. These groups could set prices and quality standards. The colony also set standards for weights and measures.

Puritans disliked fancy items. The colony tried to regulate spending on luxury goods. They frowned upon items like lace and expensive silk clothing. Attempts to ban these items failed. So, laws were passed to restrict their display to only the wealthiest colonists.

People and Places

Most of the people who arrived in the first 12 years came from two regions in England. Many were from Lincolnshire and East Anglia. A large group also came from Devon, Somerset, and Dorset. These immigrants often followed their Nonconformist clergy who were leaving England. Unlike other colonies, most New England immigrants came for religious and political reasons, not just economic ones.

Many immigrants were well-off gentry and skilled craftsmen. They brought apprentices and servants, some of whom were indentured servants. Few nobles came, but some supported the colony financially. Merchants also made up a significant part of the immigrants. They helped build the colony's economy.

When the English Civil War began in 1642, immigration slowed down. Some colonists even returned to England to fight. In later years, most immigrants came for economic reasons. These included merchants, sailors, and skilled workers. After 1685, French Protestant Huguenots also arrived. Small numbers of Scots immigrated and blended into the colony. The population remained largely English until the 1840s.

Slavery existed in the colony but was not widespread. Some Native Americans captured in the Pequot War were enslaved. The most threatening ones were sent to the West Indies and traded for goods and other enslaved people. Governor John Winthrop owned a few Native American slaves. Governor Simon Bradstreet owned two black slaves. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties in 1641 included rules for treating slaves. In 1680, Bradstreet reported 100 to 120 slaves in the colony.

Where Was the Colony?

The Massachusetts colony was shaped by its rivers and coastline. Major rivers included the Charles and Merrimack. A part of the Connecticut River was used to transport furs and timber. Cape Ann provided harbors for fishermen. Boston's harbor offered a safe place for commercial ships. Development in Maine was mostly along the coast. Large inland areas remained under Native American control until after King Philip's War.

Colony Boundaries

The colonial charter stated that the boundaries were three miles north of the Merrimack River to three miles south of the Charles River's southernmost point. From there, it extended westward to the "South Sea" (the Pacific Ocean). At the time, no one knew how long these rivers were. This led to arguments over boundaries with neighboring colonies. The colony claimed vast lands, but in reality, it never controlled land further west than the Connecticut River valley.

The boundary with Plymouth Colony was surveyed in 1639 and agreed upon in 1640. It is still known as the "Old Colony Line."

The northern boundary was a source of dispute. In 1652, a survey party incorrectly identified the source of the Merrimack River. They carved a mark into a rock (now Endicott Rock). This line, when extended eastward, reached the Atlantic near Casco Bay in Maine.

This expanded claim led Massachusetts to try and control southern New Hampshire and Maine. This conflicted with land grants owned by John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges. The Mason heirs' claims led to the formation of the Province of New Hampshire in 1679. The current boundary with New Hampshire was set in 1741. In 1678, the colony bought the Gorges heirs' claims. This gave them control over the territory between the Piscataqua and Kennebec Rivers. Massachusetts kept control of Maine until it became a state in 1820.

The colony surveyed its southern boundary in 1642. This line was south of today's boundary and was protested by Connecticut. Most of Massachusetts's current boundaries were set in the 1700s. The eastern boundary with Rhode Island was a major exception. It required many legal battles, even Supreme Court rulings, before it was settled in 1862.

Lands that once belonged to the Pequots were divided after the Pequot War. These lands were in what is now Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. Massachusetts briefly controlled Block Island and the area around Stonington, Connecticut. However, Massachusetts lost these territories in the 1660s when Connecticut and Rhode Island received their own royal charters.

Towns and Growth

- Weymouth: 1622 (part of Plymouth Colony; joined Massachusetts Bay in 1630)

- Gloucester: 1623 (Dorchester Company)

- Chelsea: 1624

- Braintree: 1625

- Quincy: 1625

- Naumkeag (later Salem): 1626 (Dorchester Company)

- Beverly: 1626 (originally part of Salem, incorporated 1668)

- Duxbury, Massachusetts: settled 1627 (Plymouth Colony), incorporated 1637

- Charlestown: 1628 (first capital, now part of Boston)

- Lynn: 1629

- Saugus: 1629

- Manchester-by-the-Sea (Jeffery's Creek): 1629

- Marblehead: 1629 (settled as a plantation of Salem, incorporated 1639)

- Boston: 1630 (from Shawmut and Trimountaine)

- Medford: 1630

- Mystic (now part of Malden): 1630

- Everett: 1630 (settlement)

- Watertown: 1630 (on land now part of Cambridge)

- Newtowne (now Cambridge): 1630 (near Harvard Square)

- Roxbury: 1630 (now part of Boston)

- Dorchester: 1630 (now part of Boston)

- Newton: 1630

- Marshfield: 1632

- Ipswich: 1633

- Milton: 1634

- Attleboro: 1634

- Agawam: 1635 (originally administered by Connecticut Colony; joined Massachusetts 1640)

- Concord: 1635

- Hingham: 1635

- Newbury: 1635

- Dedham: 1635 (settled as Contentment, renamed Dedham and incorporated 1636)

- Winthrop: 1635

- Menotomy (now Arlington, then part of Newtowne): 1635

- Scituate: 1636

- Andover: 1636 (split into Andover and North Andover in 1856)

- Springfield: 1636 (originally administered by Connecticut Colony; joined Massachusetts 1640)

- Taunton: 1637

- Brookline: 1638 (settled as Muddy River, part of Boston until incorporated 1705)

- Rowley: 1638

- Salisbury: 1638

- Reading: 1639 (Lynn Village, renamed and incorporated 1644)

- Sandwich: 1639 (first settled 1637)

- Sudbury: 1639

- Winchester: 1640 (founded as part of Charlestown, incorporated as Waterfield 1640, incorporated 1850)

- Chicopee: 1640 (settled as Nayasett)

- Haverhill: 1640

- Malden: 1640 (founded as part of Charlestown, incorporated 1649)

- Woburn: 1640

- Methuen: 1642 (founded as part of Haverhill, incorporated 1725)

- Longmeadow: 1644

- Andover: 1646 (original settlement is now in North Andover)

- Framingham: 1647

- Natick: 1651

- Eastham: 1651

- Medfield: 1651

- Billerica: 1653 (Founded as Shawshin, incorporated 1655)

- Chelmsford: 1653 (incorporated 1655)

- Lancaster: 1653

- Lowell: 1653 (Founded as East Chelmsford, formally incorporated 1826)

- Northampton: 1654 (incorporated 1653)

- Groton: 1655

- Dunstable: 1656

- Hadley: 1659

- Middleton: 1659

- Holliston: 1659

- Marlborough: 1660

- Westfield: 1660

- West Springfield: 1660

- Brookfield: 1660

- Milford: 1662

- Mendon: 1667

- Middleborough: 1669

- Deerfield: 1673

- Worcester: 1673

Important Leaders and Families

- Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643) was an important religious figure. Historians have called her "the most famous—or infamous—English woman in colonial American history."

- John Oliver (c. 1616, died 1646) was a Puritan minister.

Lasting Impact

The families who settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony had a big impact on American politics. Thirteen presidents of the United States can trace their family lines back to these early settlers. These presidents include John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush.

See also

In Spanish: Colonia de la bahía de Massachusetts para niños

In Spanish: Colonia de la bahía de Massachusetts para niños

- History of Massachusetts

- History of the Puritans in North America

- List of colonial governors of Massachusetts

- List of members of the colonial Massachusetts House of Representatives

- David Pulsifer — Editor of the Records of the Colony of New Plymouth in New England from 1633 to I679