Edward Coke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Coke

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Chief Justice of the King's Bench | |

| In office 25 October 1613 – 15 November 1616 |

|

| Appointed by | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir Thomas Fleming |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Montagu |

| Chief Justice of the Common Pleas | |

| In office 30 June 1606 – 25 October 1613 |

|

| Appointed by | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir Francis Gawdy |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Hobart |

| Attorney General for England and Wales | |

| In office 10 April 1594 – 4 July 1606 |

|

| Appointed by | Elizabeth I |

| Preceded by | Thomas Egerton |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Hobart |

| Solicitor General for England and Wales | |

| In office 16 June 1592 – 10 April 1594 |

|

| Appointed by | Elizabeth I |

| Preceded by | Thomas Egerton |

| Succeeded by | Sir Thomas Fleming |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 February 1552 Mileham, Breckland, Norfolk, England |

| Died | 3 September 1634 (aged 82) |

| Spouses | Bridget Paston (died 1598) Elizabeth Cecil (died 1646) |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Profession | Barrister, Politician, Judge |

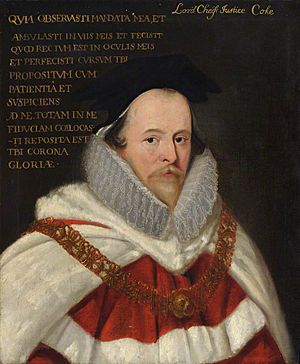

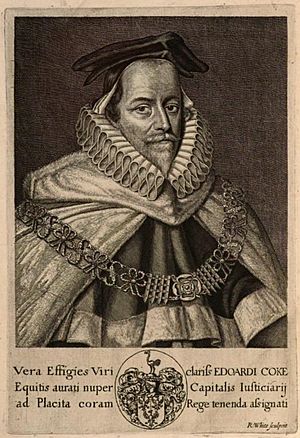

Sir Edward Coke (born February 1, 1552 – died September 3, 1634) was an important English barrister (a type of lawyer), judge, and politician. Many people think he was the greatest legal expert of the Elizabethan and Jacobean times.

Coke came from a well-known family. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and then at the Inner Temple to become a lawyer. He became a barrister in 1578. As a lawyer, he worked on many important cases. He later became a politician, serving as Solicitor General and then Speaker of the House of Commons.

Later, as Attorney General, he led big court cases against famous people like Sir Walter Raleigh. Because of his good work, he was made a knight and then a judge, becoming Chief Justice of the Common Pleas.

As a judge, Coke believed the King should follow the law, just like everyone else. He also said that Parliament's laws could be invalid if they went against "common right and reason." These ideas made the King, James I, unhappy. So, Coke was moved to a different court, the King's Bench, where the King hoped he would cause less trouble.

But Coke continued to challenge the King's power. This led to him being fired from his judge job in 1616. After that, he went back to Parliament. There, he became a leader of the group that opposed the King. He helped create important laws like the Statute of Monopolies, which limited the King's power to grant special business rights. He also helped write the Petition of Right, a document that protected people's rights. This document is seen as one of England's most important, along with the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689.

Today, Coke is best known for his legal books, especially his Institutes and his Reports. These books are still very important for understanding English law. His ideas also greatly influenced the laws and rights in the United States, including parts of the United States Constitution.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Edward Coke was born on February 1, 1552, in Mileham, Norfolk, England. He was one of eight children, and the only boy. His family had been involved in law for a long time.

His father, Robert Coke, was a lawyer who bought several estates in Norfolk. His mother, Winifred Knightley, also came from a family of lawyers. Her family had strong connections to important legal figures.

When Edward was nine, his father died. Two years later, his mother married Robert Bozoun, a property trader. Bozoun taught Coke important lessons about business and honesty, which helped him in his future career.

Education and Becoming a Lawyer

In 1560, at age eight, Coke started school at the Norwich Free Grammar School. He learned about history, writing, and public speaking. He was known as a hard-working student.

After Norwich, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1567. He studied there for three years but left without a degree. He was proud of his time at Cambridge, calling it one of the "eyes and soul of the realm."

In 1571, he moved to London to study law at Clifford's Inn. This was the first step in becoming a lawyer. Students learned by discussing legal cases and practicing arguments. Coke loved studying legal documents.

In 1572, he moved to the Inner Temple, a more advanced law school. He spent his time listening to lawyers argue cases in Westminster Hall. He became a barrister on April 20, 1578. This was very fast, as most students took eight years to finish. People said he was very smart and knew a lot about the law.

Working as a Barrister

After becoming a barrister, Coke quickly started working. His first case was in 1581, called Lord Cromwell's Case. He successfully defended his client, Mr. Denny, against a charge of slander. Coke was very proud of how he handled this case.

The next year, he was chosen as a "Reader" at Lyon's Inn. This meant he taught law students, which further increased his good reputation.

Coke also worked closely with the Howard family, who were powerful nobles. He helped them with legal issues, especially when the Crown tried to take their lands. He proved that some evidence against them was false.

He was involved in other famous cases, like Shelley's Case and Slade's Case. Slade's Case was important for the development of contract law, and Coke's arguments helped define what a "consideration" is in a contract.

Politics and Public Service

Coke's legal work for the Howard family helped him get into politics. In 1589, he was elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Aldeburgh.

Under Queen Elizabeth I

Solicitor General and Speaker

In 1592, Coke became Solicitor General. This was a big job, helping the Queen with legal matters. He was also chosen as Speaker of the House of Commons. This meant he was in charge of leading debates in Parliament.

During his time as Speaker, Parliament faced challenges. The Queen needed money for a war against Spain. Some MPs wanted to discuss religious issues, which the Queen did not allow. Coke, as Speaker, tried to delay these debates to support the Queen. He was very loyal to Queen Elizabeth I.

Attorney General

In 1594, Coke became Attorney General. This was the main prosecutor for the Crown. He worked closely with the powerful Cecil family.

He handled many cases involving treason, which is betraying your country. He also dealt with religious conflicts. A major challenge was the rivalry between Robert Cecil and Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex.

Essex eventually rebelled against the Queen. Coke led the case against him, charging him with treason. Essex was found guilty and executed. Coke's role in this case showed his strong loyalty to the Crown.

Under King James I

When Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. Coke quickly gained the new King's favor and was knighted. He continued as Attorney General.

One of his first big cases under James I was the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh. Raleigh was accused of plotting against the King. Coke's behavior during this trial was criticized because he used strong words and weak evidence to get a conviction. Raleigh was found guilty and imprisoned.

Coke also led the prosecution of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators in 1605. This was an easier case, as the conspirators had no legal defense. They were all sentenced to death. This was Coke's last major prosecution before becoming a judge.

Work as a Judge

Coke became a judge in 1606, first as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. People noticed that he was fair and independent in his new role.

Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

Challenging the High Commission

As a judge, Coke started to challenge groups he had supported before. His first target was the Court of High Commission, a powerful church court. This court made people take an oath that could trap them, which was very unpopular.

Coke believed that this court had too much power and went against common law. He argued that no one should be forced to reveal their "secret thoughts." He issued many "writs of prohibition" to stop the High Commission from acting outside its proper limits.

This led to a big argument with King James I. The King believed he had the right to decide legal cases himself. But Coke famously told the King that he was "subject to the law." He explained that understanding the law required special training and experience, not just being King. This was a brave stand, and Coke was only saved from punishment by a powerful ally.

Dr. Bonham's Case

One of Coke's most famous decisions was in Dr. Bonham's Case in 1610. In this case, he suggested that if a law made by Parliament was against "common right and reason," the common law courts could declare it void.

This idea was very important. In England, the idea of Parliamentary sovereignty (that Parliament's laws are supreme) became the rule. But in the United States, Coke's idea was used to support the power of courts to review laws and declare them unconstitutional. This is known as judicial review in the United States.

Chief Justice of the King's Bench

In 1613, Coke was moved to the Court of King's Bench. The King and his advisors hoped this would limit Coke's influence. However, Coke continued to challenge the King's power.

In 1616, a case about "commendams" came up. The King was using a special writ to allow a bishop to keep church money without doing his duties. Coke and the other judges said this was illegal. When the King got angry, Coke stood his ground, saying he would always do what was right for a judge.

This was the final straw for King James I. On November 14, 1616, Coke was fired from his job as Chief Justice. This made many people in England upset, as they saw it as the King interfering with justice.

Return to Politics

After being fired, Coke returned to Parliament in 1620 as an MP for Liskeard. The King actually wanted him to support his plans, but Coke became a leading member of the opposition. He used his experience to speak out on important issues like economics and law. He later served as an MP for other areas, including Norfolk and Buckinghamshire.

Monopolies and Royal Power

Coke used his position in Parliament to attack "patents" or "monopolies." These were special rights granted by the King to certain people or companies to control a specific business, like selling salt. The King liked these because they brought him money, but they often hurt ordinary people by raising prices.

Coke believed these monopolies were unfair and illegal. He helped create a committee in Parliament that got rid of many of them. He also helped write the Statute of Monopolies, which limited the King's power to grant such rights. This law was a big step towards limiting the King's power.

King James I was very angry about this. He tried to stop Parliament from discussing these matters, saying they were "above your reach." But Parliament, led by Coke, stood firm. They wrote a document saying their rights were the "ancient and undoubted birthright" of English subjects. The King ripped this page out of the Parliament's record and dissolved Parliament. Coke was then put in the Tower of London for nine months.

Protecting Liberties: The Petition of Right

After James I died in 1625, his son Charles I of England became King. Charles I also tried to raise money without Parliament's approval and imprisoned people who refused to pay. This made many people angry.

Coke famously declared that "the house of an Englishman is to him as his castle," meaning people's homes should be safe from soldiers. Parliament responded by insisting on the importance of the Magna Carta, which protected people from being imprisoned without trial.

Coke helped prepare the Resolutions, which said that no tax could be collected without Parliament's permission, and soldiers could not be forced into private homes. He presented these ideas to the House of Lords, citing many past laws and cases.

Coke played the main role in writing the Petition of Right in 1628. This document confirmed the rights and freedoms of English people. It said that people could not be taxed without Parliament's approval, had the right to Habeas Corpus (meaning they couldn't be held without a reason), and that soldiers couldn't be forced into homes.

The Petition of Right was approved by both houses of Parliament and became a very important law. It is considered one of the three most important documents for English civil liberties, along with the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689.

Retirement and Death

When King Charles I decided to rule without Parliament in 1629, Coke retired to his home. He spent his time working on his legal books. He said the Petition of Right was his "greatest inheritance."

Coke died on September 3, 1634, at the age of 82. He was buried in St. Mary's Church in Tittleshall, Norfolk. His monument has a Latin inscription that calls him "Father of twelve children and thirteen books."

Personal Life

In 1582, Coke married Bridget Paston. She came from a family of lawyers. They had ten children together. Bridget was a strong and independent woman who managed their household.

After Bridget died in 1598, Coke married Elizabeth Hatton. This marriage was partly for her wealth and connections. It was a difficult marriage, as Elizabeth was strong-willed. They had two daughters.

One of his daughters, Frances, caused a scandal by leaving her husband. Coke had arranged her marriage to gain favor with the King, but Frances and her mother strongly opposed it. Despite this, Coke and Frances later made up, and she cared for him in his final years.

Writings and Legacy

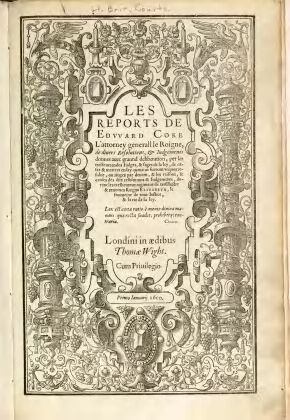

Coke is most famous for his written works: his thirteen volumes of Law Reports and his four-volume Institutes of the Lawes of England. These books collected and explained the laws of his time.

Reports

Coke's Law Reports were like a collection of court judgments and legal notes he made throughout his career. They started as notes from his student days and grew into a huge collection.

These Reports are highly praised by legal experts. Even his rival, Francis Bacon, said they contained "infinite good decisions." They helped shape English law and are still studied today.

Institutes

Coke's other main work was the Institutes of the Lawes of England. This was a four-volume book that explained different areas of law. The first volume, Commentary upon Littleton, was the most famous. It was a guide for law students written in English.

These Institutes became a standard textbook in England and later in the United States. Many important American legal figures, like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, were influenced by Coke's writings. His work helped shape ideas about liberty and rights in America.

Legal Ideas

Coke believed that judges were the best people to interpret and make laws, followed by Parliament. He also strongly believed that the King must follow the law. He thought that judges, through their special training, had a deep understanding of the law that others could not easily grasp.

His ideas were challenged by others, like Thomas Hobbes, who thought the King's authority was the source of law. But Coke's view that the law was based on "reason" (the logic used by judges) was very influential.

Legacy and Influence

Coke's challenges to the church courts helped lead to the idea of the right to silence, meaning you don't have to speak against yourself in court. His work also helped develop modern contract law and judicial independence.

The Statute of Monopolies, which Coke helped create, was an important step towards the English Civil War and the shift to a more capitalist economy in England.

Coke's ideas were very important in the United States. His decision in Bonham's Case was used to argue against unfair laws like the Stamp Act 1765. His ideas also influenced parts of the United States Constitution, including the Fourth Amendment (about privacy in homes) and the Third Amendment (about soldiers in homes). The famous saying "an Englishman's home is his castle" comes from Coke's writings.

Character

Coke was known for loving and working very hard at the law. He was a powerful and effective lawyer, though sometimes seen as harsh or overbearing in court. He was determined to win his cases.

He made a lot of money by buying land with unclear ownership. He would then use his legal knowledge to fix the ownership issues, making the land more valuable. It's said that King James I once told him he had enough land, but Coke asked for "just one acre more" and then bought a very expensive estate.

Coke's last words were "Thy kingdom come, thy will be done."

Works

- (in en) Institutes of the laws of England. 1st part (1 ed.). London: Society of Stationers. 1628. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=7194824.

- (in en) Institutes of the laws of England. 2nd part (2 ed.). London: Miles Flesher per William Lee & Daniel Pakeman. 1642. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6496498.

- (in en) Institutes of the laws of England. 3d part (2 ed.). London: Miles Flesher per William Lee & Daniel Pakeman. 1648. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6495661.

- (in en) Institutes of the laws of England. 4th part (2 ed.). London: Miles Flesher per William Lee & Daniel Pakeman. 1644. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6494500.

- (in en) Reports. 1. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1826. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6819706.

- (in en) Reports. 2. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1826. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6826930.

- (in en) Reports. 3. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1826. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6823708.

- (in en) Reports. 4. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1826. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6825289.

- (in en) Reports. 5. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1826. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6821887.

- (in en) Reports. 6. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1826. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6828919.

- (in en) Reports. Analytical index. London: Joseph Butterworth. 1827. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6936296.

Images for kids

-

The monument to Edward Coke in St. Mary's Church, Tittleshall in Norfolk.

-

Coke's descendant Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester (fifth creation).

See also

In Spanish: Edward Coke para niños

In Spanish: Edward Coke para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |